THE CALL BUILDING: SAN FRANCISCO'S FORGOTTEN SKYSCRAPER: Difference between revisions

(PC and protected) |

m (Protected "THE CALL BUILDING: SAN FRANCISCO'S FORGOTTEN SKYSCRAPER": finished essay [edit=sysop:move=sysop]) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 14:57, 2 January 2009

Historical Essay

by Ellen Klages

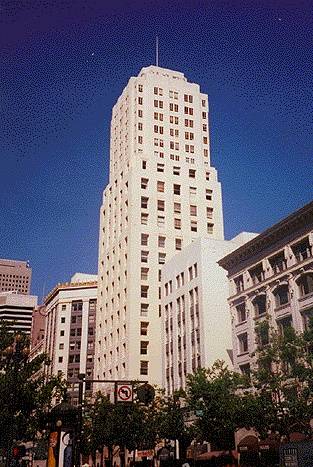

Call Building 1997

Like many historic buildings, the Claus Spreckels ("Call") Building no longer exists except in photographs or in the hand-tinted images of turn-of-the-century postcards. Its magnificent domed presence once dominated a city skyline that has long since disappeared.

But unlike most forgotten landmarks, the Call Building still remains. Its interior has been gutted and redone, its exterior completely changed, yet the pale stone tower at the corner of Third and Market Streets is still standing, ninety-four years after it first opened its doors.

Today it seems as modern and nondescript as a hundred other buildings. But in its basement there are massive stone arches, mosaic tiles on the floor of a storage bin, and rosebud friezes on the high ceiling. On the upper floors office doors boast bronze doorknobs ornately monogrammed with the initials "CS."

These are the only clues that the Call Building has not always been what it seems, that once an unknown admirer had written:

"It is, per se, a beautiful building--that is the unanimous verdict. After that it is imposing, magnificent, costly, a pride to San Francisco, a monument to the good taste and enterprise of its owner and builder, Claus Spreckels; the greatest newspaper building in the world, the handsomest of tall buildings, the tallest of the tall buildings west of Chicago--all these things and more; but first, last and all the time, it is the most beautiful building." 1

In September of 1895, the first ceremonial shovel of sand was removed from a 70 feet x 75 feet lot at the corner of Third and Market Streets. The site of the old Johnson House Building had been purchased in April of that year, and the former structure torn down to make way for a modern office building that would be a monument to its multi-millionaire owner, Claus Spreckels.2

PROGRESS AND REMODELING

The Call Building had survived the earthquake and fire, but in the 1930s it faced an enemy even more destructive--progress. Some of the sandstone on the upper floors needed to be repaired or replaced, but rather than restore the forty-year-old landmark to its prime, its owners decided to remodel it into a more modern, efficient, and economical building.

Architect Albert Roller drew up plans to change the classic domed tower into a Moderne block, with twenty-one full stories of usable, rentable office space.

With no architectural heritage societies, preservationists, or concerned citizens to decry the loss, scaffolding and hoist-cages were erected in September of 1937. Preparations were made for removing "the uneconomical top stories" (the dome). Piece by piece the terra cotta ornaments were removed and discarded. By November the dome was half gone, as if some giant knife had cut it in two; by January of 1938 there was no dome at all.

Steel work extended the square sides of the building up to form a slightly inset cube, six stories high. The decorative friezes, columns, arched windows, and other "inefficient" ornamentation were removed, and the whole building was refaced with a cream-colored concrete, creating a severe, unadorned vertical shaft which was critically acclaimed as a feat of remodeling.

The interior offices and corridors were also "modernized" (although the doorknobs in the older portion of the building still bear the "CS" monogram; interior stairs are marble and wrought iron up to the 16th floor, and steel and concrete beyond). The most striking interior change was the entrance and lobby. The arches and columns that fronted on Market Street were removed and the first three floors were faced with dark, polished granite. An entrance with a Moderne grill led into a lobby with polished black marble floors, bronze Art Deco motif elevators and curved walls of glass brick.14

In the fall of 1938 the remodeling of the Call Building into the Central Tower was completed. The building still stands at the corner of Third and Market Streets.

Once proclaimed the tallest building for thousands of miles and the "handsomest commercial edifice in the world," in the space of a few decades the Call Building went from being one of the most prominent structures in the country to being just another downtown building. For most San Franciscans, the Call Building is just a piece of history, perhaps a fond memory; many have never heard of it at all. Some assume the Humboldt Building, which retained its dome and character, was once the Call. Few would suspect the Central Tower of having such a spectacular past.

--by Ellen Klages, excerpted from a longer article originally published in The Argonaut, Summer 1993, Volume 4, Number 1

Call Building 1902

Architecture of the Call Building

Claus Spreckels hired the Reid Brothers, James and Merritt, as architects for the project, as he had on many previous endeavors. (The Reid Brothers are best known for the John D. Spreckels-financed Hotel Del Coronado in San Diego, as well as for the Fairmont Hotel and the first steel-frame building on the west coast, the Portland Oregonian.) The architects' primary challenge was to design a structure that was impressive and ostentatious enough to satisfy Claus Spreckels, on a lot that measured only 75 feet by 70 feet.

Their design was an architectural masterpiece, a square tower of white marble (the finished structure would be light sandstone) topped by a magnificent bronze and marble dome (actually built of terra cotta). A monumental column-flanked entrance and lobby rotunda was set into a three-story granite pedestal, topped by a seven-story unornamented shaft. The next two stories were decorated with friezes, colonnades, and Renaissance pillars. The 16th story was circular, forming the base of the dome, with octagonal turrets on each corner of the story below. The dome itself was 60 feet in diameter and contained three additional floors of space; it was topped by an ornamental lantern which in turn was surmounted by a flagpole. The upper stories were to be identical on all four sides; because of its corner location and its height, the building could be seen from any direction.

"It is the first object that attracts the eye as one crosses the Bay towards San Francisco. From the summit of every hill as one views the city it rivets the attention of the spectator, reminding him forcibly of the story of the giant holding an army of pigmies at bay."4

The sheer amount of hype that heralded the planning and groundbreaking for this building was unprecedented in San Francisco history. An August 1895 issue of the Call devoted its entire front page to a steel engraving of the architects' rendering along with flowery descriptions of its proposed charms. In subsequent issues congratulatory missives from journalists all over the west were printed, each more poetic than the last: "this will surely be the greatest and handsomest newspaper building in the world, one of the marvels of the age of skyscraping," and even "the crowning achievement of mankind in the Western world." Many also took the opportunity to point out how majestically it would tower over the home of its rival and neighbor, the Chronicle Building.

When M. H. DeYoung had built a new 160-foot home for the Chronicle six years earlier, its ten stories, clock tower, and modern steel-frame construction had been considered the apex of the builder's art. Until the late 1870s, buildings over one or two stories were constructed of masonry, each floor resting solidly on the previous one. (The 16-story Monadnock Building of Chicago was the tallest masonry structure built; the walls of its basement level were more than 15 feet thick in order to support its massive weight.) After the Chicago fire of 1879, a few young architects developed a "modern" method of construction which removed dead weight from the floors and walls of a building and supported it on a framework of iron and steel girders and beams from which stone or masonry walls could be hung. Without the limits of masonry construction, buildings could be erected taller and taller; when the 265-foot Masonic Temple was built in Chicago in 1891 it was considered one of the seven wonders of the modern world, and many thought that it would remain the tallest building in the world for decades, if not centuries, to come.

The new 18-story Call Building was to be 315 feet from the street to the tip of the lantern on its dome, and therefore the tallest building in San Francisco, on the Pacific Coast, and west of Chicago.5 Since it could not compete for absolute superlatives in height, the local papers noted proudly that the Call Building would be "the tallest structure in the United States in proportion to its ground area."

From its inception, the building was a cause for excitement and celebration in the city. Public reaction was overwhelmingly positive. Civic leaders were pleased to have Mr. Spreckels put San Francisco on the map architecturally, and most citizens were in awe of the sheer size of the proposed monolith. They'd never seen anything like it before.

Some of the excitement was based on the fact that the Call Building was likely to be San Francisco's first and only true skyscraper. In the summer of 1895, the Fire Committee and the Board of Supervisors had passed an ordinance limiting the height of any commercial building in the city to 125 feet on streets 100 feet or more in width, and to a height of only 100 feet on other thoroughfares.6 (The Call Building was exempt from the ordinance since contracts had been signed and it was already in progress.) The most pressing concern for the Board of Supervisors was the (widely held) fear that tall buildings would simply topple over in an earthquake; another issue was that fire-fighting equipment could only be used to a height of 100 feet. Some adherents of the ordinance also claimed that extremely tall buildings blotted out the light and restricted air flow to other buildings; others simply believed that skyscrapers were an offense against God and nature.

BUILDING A LANDMARK

Few considered the Call Building offensive, as the beauty of its design seemed to offset fears of its extreme height, and construction proceeded as planned. Tall board fences were erected around the site and excavation for the foundation began in December of 1895. In order to make the building "earthquake-proof': a two-inch slab of concrete was poured on the sand bed 25 feet below street level; for stability the slab extended nine feet beyond the perimeter of the building on all sides. A grid of steel beams was embedded in the concrete, upon which the supporting columns were set.

As the structure grew visible above the 20-foot fence it became a popular attraction for tourists and office workers on their lunch hours.7

Once the framing had been completed on the first six floors the stone masons began their work, hanging the walls and ornamentation. When several stories were finished, plumbers and pipe-layers began their labors, followed by interior masons. The Call Building was designed not only to be earthquake proof but absolutely fireproof. Concealed by its stone facing were walls of brick 22 inches thick. Each floor was insulated with concrete; girders and beams were sheathed with terra cotta tiles as further protection.

After this insulation was in place, three miles of gas, steam, and water pipes and 20 miles of electric wire were conduited and sunk into partitions. Electricians were followed by concrete floor masons, and then by carpenters, plasterers, and interior decorators.

By the end of 1897, Claus Spreckels had spent over one million dollars on the construction of his new building, nearly every cent of it on local labor and materials. The interior was as modern and elegant as the facade; it was one of the first structures in the city to use electricity as its sole source of lighting. Each floor had fourteen offices arranged around its perimeter, which provided daylight in every room. Each office had a large view window, a coat closet, a lavatory, and a radiator, and every other room was furnished with a free-standing fire-proof safe. The floors were maple, the window frames and doors hardwood, and all offices featured polished oak wainscoting, ornamental stucco, and plaster walls tinted a pastel sage green. (Corridor walls were buff.) The corridors on each floor had "champion pink" marble wainscotting and maple floors.

The marble rotunda of the lobby had a mosaic floor--with a circular motif bearing the monogram "CS" ( as did every doorknob in the building) and three bronze doors. The door to the left led to the business offices of the Call; the door to the right to the Colombian Bank. A visitor who chose the center door was greeted by the bright copper (electroplated wrought iron) grillwork of the cages of the three high-speed elevators. The elevators served the building from lobby to dome (one also traveled to the Call's pressroom in the basement), ascending to the 19th floor in less than a minute and descending "quickly but without danger or nausea." Heartier souls could climb the nineteen stories on wrought iron and marble stairs.

Except for the elevator mechanism (in the dome) and the presses of the Call (in the basement), all machinery was located 300 feet away in a separate building on Stevenson Street which also housed the editorial and art departments of the Call.9 The Stevenson Annex contained boilers for the Call Building's steam heat, electric dynamos and engines for the lighting, and pumps for the artesian wells located beneath it. (Pressure in the city water mains wasn't strong enough to pump beyond the 12th floor.)

On October 23, 1897, the fence around the construction site was torn down as a crowd of hundreds waited for a first glimpse of the building's heralded front entrance. When the last board was torn down and the granite facade with its marble figures and carved lintel appeared, the entire crowd erupted in a spontaneous cheer for the new commercial palace.

Two months later, the Call published a commemorative number -- "the New Era edition" -- to celebrate the grand opening of the building, with a full-page, full-color lithograph of its new home as the cover.

On the evening of Friday, December 17th, crowds were treated to a spectacular light show to celebrate the city's newest attraction:

"As the beacon fires of old blazed forth to announce tiding of good to all people, so the Call Building announced a new era of prosperity to the people of the state and to the Golden Coast."10

That evening, at dusk, a single light burned in the rotunda. As darkness fell the crowd outside grew quiet until, as if by magic, all the lights in the building were turned on simultaneously--from the basement to the lantern on the dome--and "the whole vast pile suddenly shone forth in a blaze of glory."

Hundreds of people stood along Market Street or on the hills and rooftops of San Francisco to witness the spectacle. Hundreds, possibly thousands more lined the shores of the East Bay from San Pablo to what was then Hayward. Except where it was blocked from view by the natural slopes of the hills, the building was visible from almost anywhere in the Bay Area; its glow was seen as a pillar of light as far away as San Jose and Santa Rosa. In a world where electricity was still a novelty, it was the brightest object for literally thousands of miles, and so was "a spectacle that will be told of in after years as one of the sights of a lifetime."

As 1898 arrived, the Call Building took its place as San Francisco's most renowned landmark and as a symbol of the city's entrance into the modern, cosmopolitan world. Its tenants were the most prominent men of the time--attorneys (including former DAs, judges and state senators), bankers, accountants, and other men of commerce--and office space in the building was highly sought (and came at a premium).

It quickly became the city's most popular tourist attraction as well, and the image of the structure and its unique dome stood for San Francisco on postcards and in newspapers and rotogravure across the country.

THE EARLY TENANTS

Within the dome were four circular floors, although only one floor was used for offices. The topmost floor was tiny and was utilized only for storage and for access to the lantern. (The lantern was used by the Call to supplement its bulletins in times of historic events; it was lit with red to signal Dewey's victory in Manila in 1898.) The 18th floor had the Reid Brothers as its only tenants. The reward for their labors on the building was a large, circular office with a 360 degree view of every other structure in the city, through twelve porthole-like windows. The two lower floors of the dome were the home of the exclusive San Francisco Club (of which Adolph Spreckels, son of Claus, was president). The club had its meeting rooms, smoking rooms, and billiard room on the 17th floor; folding doors could be opened to create one continuous semi-circular room or closed for private meetings or multiple gatherings.

The 16th floor was the base of the dome proper and served as the dining room for the club. The room was ringed with twelve huge curved glass windows, and tables were arranged around its circumference so that each table had a view.11 Two hundred people could be seated in the marble, glass, bronze, and mahogany dining room, with private dining space for parties of up to ten in each of the four small turret rooms at the corners of the building.

One floor below this elegant private dining room was a cafe, the Spreckels Rotisserie, that offered the general public an opportunity to view the city "not from a windy hill or a sooty roof or small tower, but in the ease and comfort of a handsome restaurant."

The Rotisserie opened in 1898 under the management of S. Constantini; two years later it was taken over by Albert Wolff. The "ice cream parlor, cafe and restaurant" opened at 7:00 a.m. for breakfast, served lunch, tea, and dinner, and offered late night suppers for opera and theater goers until midnight. "C-A-F-E" was spelled out in two-foot metal letters outside the windows on the east and west sides of the building, and this advertisement could be seen from blocks away. Soon "dining in the clouds" was a must for every tourist, and for most city dwellers as well. The cafe was 250 feet above street level; a set of four postcards published by the Art Lithe Co. in 1903 shows a cut of the building (and an incredulous man pointing upward in disbelief), with an inset of the view available from each compass point.

It was not the first restaurant to be located on top of a skyscraper (there was one in New York and another in Boston), but it was perhaps the most elegant of its time. A full dinner included a choice of: three soups; seven hors d'oeuvres (shrimps, mayonnaise of crab); ten fish courses; five entrees (including chicken liver brochettes with new peas and fried mountain frogs with tomato sauce); two vegetables; four meat courses and ten desserts. The menu changed daily; a full dinner with wine cost one dollar.

Those who wished only a light snack could order a la carte: oyster cocktails were 25 cents; a sirloin steak or a club sandwich was 50 cents. California wines were 50 to 75 cents a quart (French wines went as high as one dollar). For another quarter an afternoon diner could enjoy vanilla, Neapolitan, strawberry or "pistache" ice cream in blissful quiet while watching the city teem below.

The restaurant was elegant, successful, and popular; the offices in the building seldom had vacancies and it was one of the premier commercial addresses in the city; the Call Building towered over the rest of the skyline as an emblem of a new era of modernity and prosperity for San Francisco.

Unfortunately, the new era lasted less than nine years.

--Ellen Klages, from The Argonaut