The Presidio Forest: Difference between revisions

m (Unprotected "The Presidio Forest": excerpted essay) |

(Changed credits from Greg Garr to Private Collection) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | ||

''by Pete Holloran '' | |||

[[Image:presidio$presidio-cemetery.jpg]] | [[Image:presidio$presidio-cemetery.jpg]] | ||

| Line 15: | Line 17: | ||

'''Mock battle practice, 1876, showing a Presidio without forest.''' | '''Mock battle practice, 1876, showing a Presidio without forest.''' | ||

''Photo: | ''Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA'' | ||

Like many of his contemporaries, Major Jones did not place much value on the indigenous landscape. The sand dunes and dusty grasslands that turned brown every summer may have appeared glorious to wandering reporters in May, but they did not conform to others expectations of what park lands should look like. The tidal marshes that played such a central role in the Yelamu economy seemed wastelands to Jones and the residents of late-nineteenth-century San Francisco. The main idea, Jones wrote, is to crown the ridges, border the boundary fences, and cover the areas of sand and marsh waste with a forest that will generally seem continuous, and thus appear immensely larger than it really is. This well-ordered human landscape would accentuate the difference between post and city. In order to make the contrast from the city seem as great as possible, and indirectly accentuate the idea of the power of the Government, he wrote, I have surrounded all the entrances with dense masses of wood. (Jones 1883) To Jones, the planted forests appearance was paramount. He recognized the scenic importance of Presidio vistas and planned to leave the valleys unchanged and the views from grassy summits such as Inspiration Point unobstructed. | Like many of his contemporaries, Major Jones did not place much value on the indigenous landscape. The sand dunes and dusty grasslands that turned brown every summer may have appeared glorious to wandering reporters in May, but they did not conform to others expectations of what park lands should look like. The tidal marshes that played such a central role in the Yelamu economy seemed wastelands to Jones and the residents of late-nineteenth-century San Francisco. The main idea, Jones wrote, is to crown the ridges, border the boundary fences, and cover the areas of sand and marsh waste with a forest that will generally seem continuous, and thus appear immensely larger than it really is. This well-ordered human landscape would accentuate the difference between post and city. In order to make the contrast from the city seem as great as possible, and indirectly accentuate the idea of the power of the Government, he wrote, I have surrounded all the entrances with dense masses of wood. (Jones 1883) To Jones, the planted forests appearance was paramount. He recognized the scenic importance of Presidio vistas and planned to leave the valleys unchanged and the views from grassy summits such as Inspiration Point unobstructed. | ||

| Line 23: | Line 25: | ||

Several critics were quick to raise objections to this massive tree planting effort. In 1892 post commander Colonel William Montrose Graham derided the tree planting for taking up 400 acres that could be used for training exercises. In language eerily prescient of present-day issues regarding public parks, Graham also objected to the dense thickets that are being formed, which makes shelters and secure hiding places for the tramps that infest the reservation. (Thompson n.d.) A few years later Colonel Graham raised strenuous objections to additional tree plantings. He stridently opposed a plan to plant 60,000 Monterey pines in 40 acres along the southwest border because the growing garrison would eventually require those lands for training purposes. It is urgently recommended, he wrote in one scathing letter, that the planting of more trees be prohibited by the proper military authorities. He was overruled and the massive plantings proceeded. (Thompson n.d.) | Several critics were quick to raise objections to this massive tree planting effort. In 1892 post commander Colonel William Montrose Graham derided the tree planting for taking up 400 acres that could be used for training exercises. In language eerily prescient of present-day issues regarding public parks, Graham also objected to the dense thickets that are being formed, which makes shelters and secure hiding places for the tramps that infest the reservation. (Thompson n.d.) A few years later Colonel Graham raised strenuous objections to additional tree plantings. He stridently opposed a plan to plant 60,000 Monterey pines in 40 acres along the southwest border because the growing garrison would eventually require those lands for training purposes. It is urgently recommended, he wrote in one scathing letter, that the planting of more trees be prohibited by the proper military authorities. He was overruled and the massive plantings proceeded. (Thompson n.d.) | ||

Presidio neighbors objected to the fast-growing eucalyptus trees that blocked their views. They did not appreciate the Army's desire to accentuate the boundary between post and city. The Government made a mistake when it planted eucalyptus trees along the southern boundary of the Presidio reservation, a journalist reported in the April 1895 of the ''San Francisco Real Estate Circular''. In spite of protests from property-owners, the Army insisted on keeping what the reporter called an eyesore and interceptors of the finest view in the country. | Presidio neighbors objected to the fast-growing eucalyptus trees that blocked their views. They did not appreciate the Army's desire to accentuate the boundary between post and city. The Government made a mistake when it planted [[Eucalyptus Rush|eucalyptus trees]] along the southern boundary of the Presidio reservation, a journalist reported in the April 1895 of the ''San Francisco Real Estate Circular''. In spite of protests from property-owners, the Army insisted on keeping what the reporter called an eyesore and interceptors of the finest view in the country. | ||

By 1901 the Army realized that it needed to develop a systematic and permanent plan of improvement for the Presidio landscape rather than the haphazard approach that had characterized previous efforts. The Army asked for expert advice from the U.S. Forest Service, then in its early years. The forester found that the 420 acres of plantings were too crowded and required extensive thinning. The Army agreed that plantings had been carried out without a plan in the past and announced their intention to manage the forest more intensively. (Thompson n.d.) | By 1901 the Army realized that it needed to develop a systematic and permanent plan of improvement for the Presidio landscape rather than the haphazard approach that had characterized previous efforts. The Army asked for expert advice from the U.S. Forest Service, then in its early years. The forester found that the 420 acres of plantings were too crowded and required extensive thinning. The Army agreed that plantings had been carried out without a plan in the past and announced their intention to manage the forest more intensively. (Thompson n.d.) | ||

| Line 39: | Line 41: | ||

Attitudes about the Presidio's indigenous landscape have changed over the years. For several thousand years indigenous peoples depended on the landscape for all their needs and managed it for diversity. For a hundred years -- a relatively short time -- another attitude held sway. According to this view, the barren landscape required radical transformation; the wastes were to be cloaked in evergreen trees. Cultural attitudes toward the land have evolved, though, and for many visitors biological diversity is once again a paramount value. | Attitudes about the Presidio's indigenous landscape have changed over the years. For several thousand years indigenous peoples depended on the landscape for all their needs and managed it for diversity. For a hundred years -- a relatively short time -- another attitude held sway. According to this view, the barren landscape required radical transformation; the wastes were to be cloaked in evergreen trees. Cultural attitudes toward the land have evolved, though, and for many visitors biological diversity is once again a paramount value. | ||

[excerpted from "Seeing the Trees Through the Forest: Oaks and History in the Presidio" in [http://www.citylights.com/book/?GCOI=87286100049340 ''Reclaiming San Francisco] (''San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1998)] | |||

[excerpted from "Seeing the Trees Through the Forest: Oaks and History in the Presidio" in ''Reclaiming San Francisco (''San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1998)] | |||

'''References ''' | '''References ''' | ||

Latest revision as of 15:40, 16 June 2014

Historical Essay

by Pete Holloran

National Cemetary in the Presidio.

Photo: Carla Lazer

By the early 1880s there was considerable interest in landscaping the Presidio using similar techniques to those used in Golden Gate Park. In March 1883 Major W. A. Jones proposed a massive tree planting program in his Plan for the Cultivation of Trees Upon the Presidio Reservation. Major Jones began with an appeal to the example of the successful operation at the Golden Gate Park of San Francisco as a model tree nursery operation. (Jones 1883)

Much of the appeal of the Presidio landscape, Jones realized, was due to its proximity to a great and growing city. San Francisco would watch very closely what the Army did to the landscape. The eyes of people of culture are upon us, he warned, and if it be worth while to plant trees on the Reservation at all, they should be planted effectively, and not dumped into the ground by the thousand, at random. (Jones 1883)

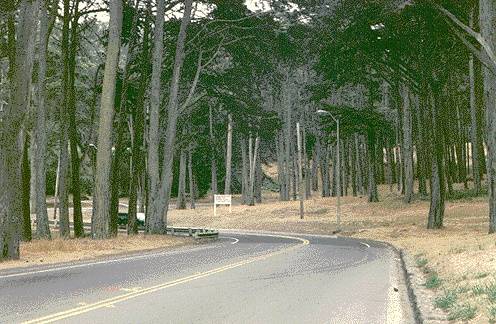

Mock battle practice, 1876, showing a Presidio without forest.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA

Like many of his contemporaries, Major Jones did not place much value on the indigenous landscape. The sand dunes and dusty grasslands that turned brown every summer may have appeared glorious to wandering reporters in May, but they did not conform to others expectations of what park lands should look like. The tidal marshes that played such a central role in the Yelamu economy seemed wastelands to Jones and the residents of late-nineteenth-century San Francisco. The main idea, Jones wrote, is to crown the ridges, border the boundary fences, and cover the areas of sand and marsh waste with a forest that will generally seem continuous, and thus appear immensely larger than it really is. This well-ordered human landscape would accentuate the difference between post and city. In order to make the contrast from the city seem as great as possible, and indirectly accentuate the idea of the power of the Government, he wrote, I have surrounded all the entrances with dense masses of wood. (Jones 1883) To Jones, the planted forests appearance was paramount. He recognized the scenic importance of Presidio vistas and planned to leave the valleys unchanged and the views from grassy summits such as Inspiration Point unobstructed.

Three years later, after Jones had been transferred from the Presidio, the first mass tree planting took place on the first celebration of Arbor Day in California. Adolph Sutro, who had paid hundreds of unemployed workers to plant trees over large portions of San Francisco, donated 3,000 trees to the post. By 1892, six years later, Army official would boast that 329,975 trees had been planted to date. The first major landscaping effort ever undertaken by the Army. (Thompson n.d.) Major Jones's warning regarding planting thousands of trees at random went largely unheeded.

Several critics were quick to raise objections to this massive tree planting effort. In 1892 post commander Colonel William Montrose Graham derided the tree planting for taking up 400 acres that could be used for training exercises. In language eerily prescient of present-day issues regarding public parks, Graham also objected to the dense thickets that are being formed, which makes shelters and secure hiding places for the tramps that infest the reservation. (Thompson n.d.) A few years later Colonel Graham raised strenuous objections to additional tree plantings. He stridently opposed a plan to plant 60,000 Monterey pines in 40 acres along the southwest border because the growing garrison would eventually require those lands for training purposes. It is urgently recommended, he wrote in one scathing letter, that the planting of more trees be prohibited by the proper military authorities. He was overruled and the massive plantings proceeded. (Thompson n.d.)

Presidio neighbors objected to the fast-growing eucalyptus trees that blocked their views. They did not appreciate the Army's desire to accentuate the boundary between post and city. The Government made a mistake when it planted eucalyptus trees along the southern boundary of the Presidio reservation, a journalist reported in the April 1895 of the San Francisco Real Estate Circular. In spite of protests from property-owners, the Army insisted on keeping what the reporter called an eyesore and interceptors of the finest view in the country.

By 1901 the Army realized that it needed to develop a systematic and permanent plan of improvement for the Presidio landscape rather than the haphazard approach that had characterized previous efforts. The Army asked for expert advice from the U.S. Forest Service, then in its early years. The forester found that the 420 acres of plantings were too crowded and required extensive thinning. The Army agreed that plantings had been carried out without a plan in the past and announced their intention to manage the forest more intensively. (Thompson n.d.)

In 1902 Jones himself commented on how the tree plantings had developed in the nearly twenty years since he wrote his proposal. The architect of the Presidio forest recommended extensive tree removal to allow the handsomest specimens a good chance to develop and also to make room for trees of different form and shades of foliage. He had developed an appreciation for the scenic and natural beauty of the Presidio and recommended removing trees in some areas to plant lupines and other wildflowers. In a striking admission, he suggested that the Army should leave the sand dune just as it is. (Thompson n.d.)

Presidio Officers housing amidst the forest and fog, mid-1990s.

Photo: Carla Lazer

Despite many initiatives and plans by various Army officers, the Presidio forest developed haphazardly and without an overall design. Various advisors had recommended removal of thousands of trees, but only a fraction had been thinned. However it developed, though, the Presidio forest had become a dominant feature of the Presidio landscape. To many, the mature tree plantings had considerable aesthetic and scenic value. In 1970, when the Army removed 340 trees for new construction, protests by neighbors reached the newspapers. Civic groups took pride in the trees and sponsored additional tree plantings over the years. In 1972, for example, the Boy Scouts planted 1,200 trees; when these died, they planted 250 more. (Thompson n.d.)

Others have explicitly rejected such tree plantings as intrusive and unnecessary. To plant a tree can be an exemplary act, but planting the wrong tree in the wrong place can have disastrous consequences. The famous photographer Ansel Adams grew up along the southern border of the Presidio and cherished the coast live oaks along Lobos Creek. As a child he explored every foot, he later remembered, and cherished the rampant and fragrant spring wildflowers. In 1910, an eight-year-old Adams was devastated by the ruthless damage caused when the Army Corps of Engineers, for unimaginable reasons, decided to clear out the [coast live] oaks and brush. (Adams et al. 1985) Decades later, Adams railed against tree plantings in the nearby Marin Headlands by Boy Scouts. "I cannot think of a more tasteless undertaking than to plant trees in a naturally treeless area, and to impose an interpretation of natural beauty on a great landscape that is charged with beauty and wonder, and the excellence of eternity." (Williams 1991)

Attitudes about the Presidio's indigenous landscape have changed over the years. For several thousand years indigenous peoples depended on the landscape for all their needs and managed it for diversity. For a hundred years -- a relatively short time -- another attitude held sway. According to this view, the barren landscape required radical transformation; the wastes were to be cloaked in evergreen trees. Cultural attitudes toward the land have evolved, though, and for many visitors biological diversity is once again a paramount value.

[excerpted from "Seeing the Trees Through the Forest: Oaks and History in the Presidio" in Reclaiming San Francisco (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1998)]

References

Jones, W. A. 1883. Plan for the Cultivation of Trees Upon the Presidio Reservation. Copy in Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley.

Thompson, Erwin N. n.d. The Presidio Forest: draft. Published in 1997 as a chapter in his Defender of the Gate: The Presidio of San Francisco, a history from 1846 to 1995. Golden Gate National Recreation Area, San Francisco.

Williams, Ted. 1991. Don't worry, plant a tree. Audubon, May 1991.

Presidio Forest, mid-1990s.

Photo: Carla Lazer