Detained on Angel Island: Difference between revisions

(added new photo) |

(added to Marin County) |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

[[Angel Island View of SF |Prev. Document]] [[Self-Organized Detainees |Next Document]] | [[Angel Island View of SF |Prev. Document]] [[Self-Organized Detainees |Next Document]] | ||

[[category:San Francisco outside the city]] [[category:Chinese]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] | [[category:San Francisco outside the city]] [[category:Chinese]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:Marin County]] | ||

Latest revision as of 12:08, 10 December 2015

Historical Essay

by H.M. Lai

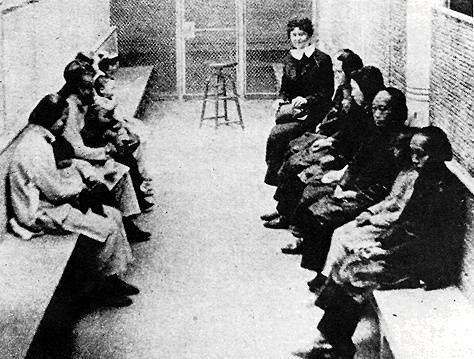

Detainees on Angel Island were kept apart by gender, and passed many days waiting to have their cases handled.

Photo: California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA

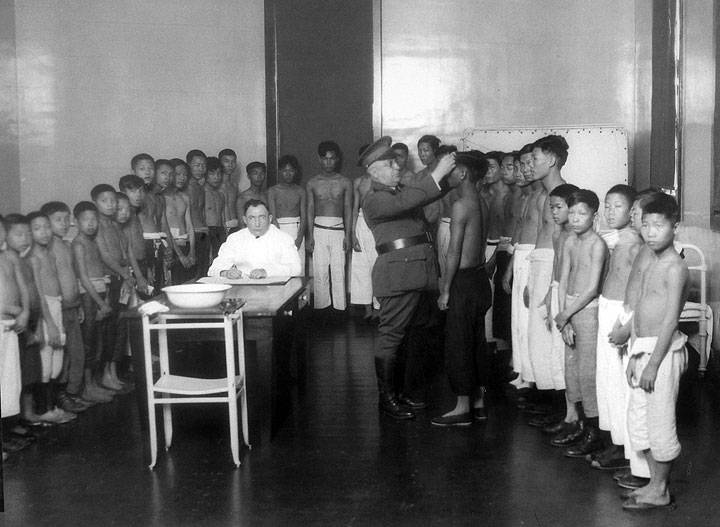

Medical examination of detained Chinese boys, c. 1920s.

Photo: National Archive

For thirty years, it was the detainees at Angel Island Immigration Station who sampled the full flavor and effect of the exclusion laws. 26 When a ship arrived at San Francisco, immigration officials climbed aboard and inspected the passengers' documents. Those with satisfactory papers could go ashore, and the remainder were transferred to a small steamer and ferried to the island immigration station where they were to await hearings on their applications for entry. In practice, most of the detainees were Chinese, although sometimes a few whites and other Asians were also held. Before the 1920s, the number included Japanese "picture brides." 27

When the ferry docked at Angel Island whites were separated from other races, and Chinese were kept apart from Japanese and other Asians. Men and women, including husbands and wives, were separated and not allowed to see or communicate with each other again until they were admitted to the country. Minor children under age twelve or so were assigned to the care of their mothers. Most of the Chinese immigrants, however, were males in their teens or early twenties.

Soon after arrival, the would-be immigrants were taken to the hospital for medical examinations. Because of poor health conditions in rural China, some immigrants were afflicted with parasitic diseases. These cases became major points of contention, because the U.S. government classified certain of these ailments as loathsome and dangerously contagious, and sought to use them as grounds for denial of admission. Arrivals with trachoma were excluded in 1903. In 1910 government officials added to the list uncinariasis or hookworm and filiariasis, and in 1917 clonorchiasis or liver fluke. Because these regulations affected primarily the Chinese, they seemed to many to be more artificial barriers erected to block their entry. Considerable protests by Chinatown leaders eventually resulted in some cases being allowed to stay for medical treatment. 28

Chinese who passed the medical hurdle were returned to their dormitories to await hearings on their applications. Men and women lived in separate communal rooms provided with rows of single bunks arranged in two or three tiers. Furnishings were spartan in nature, and privacy was minimal. Men were kept on the second floor of the detention barracks, which was surrounded by a fence to prevent escapes. Women, originally to be detained in the same building, were moved to the second story of the administration building in the 1920s. 29

At any one time about 200 to 300 males and 30 to 50 females were detained at Angel Island. Most were new arrivals, but some were returning residents whose documents were considered questionable. Also inhabiting the island were earlier arrivals whose applications had been denied and who were waiting either decisions on their appeal or orders for their departure. Mixed among the detainees were Chinese who had been arrested and sentenced to be deported, 30 as well as transients en route between China and countries neighboring the U.S., especially Mexico and Cuba. 31

Guards sat outside the dormitories' locked doors, and the Chinese were usually left alone. One Chinese matron, Ah Tai, was available at the women's dormitory to answer to their needs.32 To forestall the passing of coaching information prior to the detainees' oral examination, no inmate could receive visitors from the outside before his case had been judged. Authorities routinely opened and scrutinized letters and gift packages to and from detainees, inspecting them for possible coaching messages.

Sanitary conditions in the dormitories were barely adequate for the thrown-together transient population of strangers from all walks of life. Moreover, janitorial services were limited. Ten months after the station's opening, the acting commissioner was already criticizing the filthy conditions of the facilities. Fourteen years later, circumstances had not improved, for in 1924 the Chinese Benevolent Association bitterly complained to President Calvin Coolidge and Secretary of Labor J. J. Davis about the unhealthy conditions on the island which had allegedly caused several detainees to sicken and die. As late as 1932, the Angel Island Liberty Association, a detainees' organization, was forced to negotiate with the authorities to provide soap and toilet tissue for the detainees. 33

Deprived of organized activities within the dormitories, 34 many immigrants lolled about or laid on their bunks, most of the time worrying about their future. Some passed the time gambling, but stakes were usually small because the inmates had little pocket money. The literate read Chinese newspapers sent from San Francisco and their own books or those left behind by others. By the late 1920s or early 1930s, a phonograph and Chinese opera records were also available for the detainees' amusement. Women sometimes sewed or knitted.

Separate small, fenced, outdoor recreation yards were provided for the men and women so they could breathe fresh air and enjoy sunshine. Once a week they were escorted to the storehouse at the dock where they could select needed items from their baggage. In addition, women and children were sometimes allowed to walk on the grounds in a supervised group, a privilege which was denied to the men.

Somewhat infrequently the detainees received visits from various clergymen of Chinatown's Protestant missions, but, understandably, few were converted to Christianity. During the early 1920s, the Chinese YMCA also made regular trips to the island to show movies and teach English. 35 The most regular visitor, however, was Deaconess Katherine Maurer (1881-1962), appointed in 1912 by the Woman's Home Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church to do Chinese welfare work at the immigration station. Her work was also supported by funds and gifts from the Daughters of the American Revolution. The deaconess, who became known as the "Angel of Angel Island," helped detainees to write letters, taught English, and performed other small services, primarily for the women and children, to make detention somewhat more bearable. 36 Neither she nor other visitors, however, could change the basic conditions created by the discriminatory exclusion laws.

The Chinese held at Angel Island resented their long confinements, particularly because they knew that immigrants from other countries were processed and released within a short time. Their disgruntled feelings were fueled by the enforced idleness, and accentuated by unsatisfactory conditions at the station. Unable to change their plight, they frequently petitioned the CCBA, the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, and the Chinese consul general for help. The first petition charging mistreatment was sent only a few days after the station opened in 1910. 37

Sometimes these letters produced serious consequences beyond the expectations of the senders. For example, in 1916 the Chinese consul general in San Francisco, Xu Shanging, responded to detainees' complaints and enlisted the help of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce to investigate conditions at Angel Island. The commissioner general of immigration became irate at the consul general for bypassing diplomatic channels and had him declared persona non grata in the United States. Xu was transferred to another post in Panama. 38

Within the station, impatient and hot-headed young immigrants often took matters into their own hands and staged disturbances in the dining hall (located in the administration building) to protest the poor food and mistreatment. Such disorders were only rarely reported by the press, but enough of them evidently occurred to cause the immigration officials to post a sign in Chinese warning diners not to make trouble nor to spill food on the floor. In 1919, a large riot broke out, and troops had to be called in to restore order. A year later authorities in Washington, D.C. finally decided to improve the situation, and fuller menus were instituted. 42

After this move, complaints about the food subsided, although two more dining hall disturbances occurred in 1925; the one on June 30 again requiring troops with fixed bayonets to be called in from Fort MacDowell. On these two occasions, however, the food itself apparently was not the primary cause. 43 The frequency of these outbreaks, whatever their cause, indicates that the resentment harbored among the detainees could easily explode when sparked by a suitable issue.

--by H.M. Lai (from California History, spring 1978)

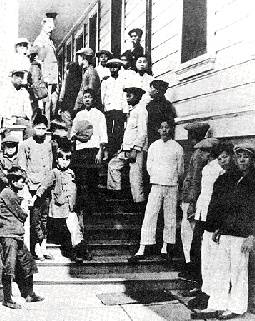

Detainees on Angel Island posing for a picture.

Photo: California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA