Folsom Street: The Miracle Mile: Difference between revisions

(added Charles Ruiz photo) |

(changed credit on 1926, 1927, 1928, and 1929 SFPL photos which came from C.R. collection) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essays</font></font> </font>''' | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essays</font></font> </font>''' | ||

''Part One by Gayle Rubin'' | ''Part One by Gayle Rubin, excerpted from "The Miracle Mile: South of Market and Gay Male Leather, 1962-1997" in'' Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture ''(City Lights: 1998)'' | ||

''Part Two from ''Black Sheets'' magazine'' | ''Part Two from ''Black Sheets'' magazine'' | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

The leather scene moved to what would become its Main Street in 1966, when Febe's and the Stud opened up at the western end of Folsom Street. Several other bars soon opened along a three-block strip of Folsom Street, establishing a core area that anchored a burgeoning leather economy with various commercial establishments, which continued to develop and expand in the 1970s to become one of the most extensive and densely occupied leather neighborhoods in the world. The area still functions as the local leather capital. As a result, the South of Market acquired a number of nicknames, including the Folsom, the Miracle Mile, and the Valley of the Kings. This last appellation was coined by local leather columnist Mr. Marcus. By the late 1970s, Mr. Marcus had given each of San Francisco's three major gay neighborhoods a nickname. The Valley of the Kings conveyed an image of powerful, cocky, independent, and sexy masculinity. It contrasted with Marcus' nickname for Polk Street, the Valley of the Queens, in reference to the older and sometimes more effeminate population of gay men associated with the area. He dubbed the Castro the Valley of the Dolls, an allusion to its hordes of young and beautiful men. By the late 1970s, the Castro was unquestionably the center of local gay politics, but the Folsom had become the sexual center. The same features that made the area attractive to leather bars made it hospitable to other forms of gay sexual commerce. Many of the non-leather gay bathhouses and sex clubs also nestled among the warehouses. Just before the age of AIDS, the South of Market had become symbolically and institutionally associated in the gay male community with sex. | The leather scene moved to what would become its Main Street in 1966, when Febe's and the Stud opened up at the western end of Folsom Street. Several other bars soon opened along a three-block strip of Folsom Street, establishing a core area that anchored a burgeoning leather economy with various commercial establishments, which continued to develop and expand in the 1970s to become one of the most extensive and densely occupied leather neighborhoods in the world. The area still functions as the local leather capital. As a result, the South of Market acquired a number of nicknames, including the Folsom, the Miracle Mile, and the Valley of the Kings. This last appellation was coined by local leather columnist Mr. Marcus. By the late 1970s, Mr. Marcus had given each of San Francisco's three major gay neighborhoods a nickname. The Valley of the Kings conveyed an image of powerful, cocky, independent, and sexy masculinity. It contrasted with Marcus' nickname for Polk Street, the Valley of the Queens, in reference to the older and sometimes more effeminate population of gay men associated with the area. He dubbed the Castro the Valley of the Dolls, an allusion to its hordes of young and beautiful men. By the late 1970s, the Castro was unquestionably the center of local gay politics, but the Folsom had become the sexual center. The same features that made the area attractive to leather bars made it hospitable to other forms of gay sexual commerce. Many of the non-leather gay bathhouses and sex clubs also nestled among the warehouses. Just before the age of AIDS, the South of Market had become symbolically and institutionally associated in the gay male community with sex. | ||

[[Image:6th-St-SE-at-Folsom-1926-SFPL 72dpi.jpg|720px]] | [[Image:6th-St-SE-at-Folsom-1926-SFPL 72dpi.jpg|720px]] | ||

| Line 39: | Line 37: | ||

'''Sixth Street looking southeast across Folsom Street, 1926, long before the neighborhood began to change.''' | '''Sixth Street looking southeast across Folsom Street, 1926, long before the neighborhood began to change.''' | ||

''Photo: | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | ||

[[Image:Folsom-St-ne-at-6th-1928-SFPL 72dpi.jpg|720px]] | [[Image:Folsom-St-ne-at-6th-1928-SFPL 72dpi.jpg|720px]] | ||

| Line 45: | Line 43: | ||

'''Folsom Street northeast across 6th Street, 1928.''' | '''Folsom Street northeast across 6th Street, 1928.''' | ||

''Photo: | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | ||

[[Image:Folsom-South-at-7th-1929-SFPL 72dpi.jpg|720px]] | [[Image:Folsom-South-at-7th-1929-SFPL 72dpi.jpg|720px]] | ||

| Line 51: | Line 49: | ||

'''Folsom Street west at 7th Street, 1929.''' | '''Folsom Street west at 7th Street, 1929.''' | ||

''Photo: | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | ||

[[Image:Folsom-Street-east-at-9th-1927-SFPL.jpg|720px]] | [[Image:Folsom-Street-east-at-9th-1927-SFPL.jpg|720px]] | ||

| Line 57: | Line 55: | ||

'''Folsom Street east at 9th Street, 1927.''' | '''Folsom Street east at 9th Street, 1927.''' | ||

''Photo: | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | ||

Revision as of 16:29, 12 July 2016

Historical Essays

Part One by Gayle Rubin, excerpted from "The Miracle Mile: South of Market and Gay Male Leather, 1962-1997" in Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, Culture (City Lights: 1998)

Part Two from Black Sheets magazine

Rubble of the Tool Box at 4th and Harrison (1971), Chuck Arnett's notorious mural stood mutely over the ruins for almost two years.

This is the city's backyard. . . . An early morning walk will take a visitor past dozens of small businesses manufacturing necessities; metal benders, plastic molders, even casket makers can all be seen plying their trades. At five they set down their tools and return to the suburbs. . . . A few hours later, men in black leather . . . will step out on these same streets to fill the nearly 30 gay bars, restaurants and sex clubs in the immediate vicinity. Separate realities that seldom touch and, on the surface at least, have few qualms about each other. --Mark Thompson (1982, 28)

Gay male leather communities have been markedly territorial in major U.S. cities. In San Francisco, leather has been most closely associated with the South of Market neighborhood since 1962. Earlier, in the 1950s, leathermen had mostly patronized the waterfront bars, such as Jacks on the Waterfront, the Sea Cow, and the Castaways. The first dedicated leather bar in San Francisco was the Why Not, which opened briefly in the Tenderloin in 1962. When the Tool Box opened later that year on the corner of Fourth Street and Harrison, it was the first leather bar located in the South of Market. The Tool Box was a sensation. It was wildly popular and even attracted nationwide media notice. Herb Caen wrote about the Tool Box in his famous San Francisco Chronicle column:

"As I noted a few days ago, some of the young fellers who hang out in the Tool Box at Fourth and Harrison wear and S or an M on their shirt pockets to indicate Sadist or Masochist. Which prompted a relieved message from Harold Call. "I'm so glad you printed that," he said. "All this time I thought it meant Single, or Married!" (Caen 1964)

The most celebrated element of the Tool Box was a huge mural painted by Chuck Arnett, a local artist who worked at the bar and whose paintings and posters were also featured at such later bars as the Red Star Saloon and the Ambush. The mural was a massive black-and-white painting that depicted a variety of tough-looking, masculine men. In 1964, when Life magazine did a story on homosexuality in America, a photograph of the Tool Box was spread across the two opening pages. (Welch & Eppridge 1964)

In it we see the mural and some of the bar patrons, including Arnett and several others who would play significant roles in San Francisco's early leather history, as the managers, bartenders, bouncers, and above all, the artists and decorators of local leather establishments. Standing next to Arnett is Bill Tellman, another artist who has contributed a great deal to the local iconography. He designed the poster for the Slot, one of the earliest leather-oriented bathhouses. He also did graphic design for the Ambush, and a made a backlit stained-glass depiction of fistfucking that eventually adorned the Catacombs.

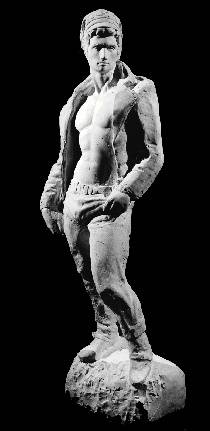

Jack H. is also in the photo. In 1965 Jack and a partner opened the Detour at 888 McAllister Street when the popularity of the Tool Box began to subside. Later he was a co-owner of Febe's, one of the first leather bars to open on Folsom Street. Jack also later opened the Slot, and some stories even credit him with having invented fistfucking at a party in his basement in 1962. Mike Caffee, another artist, is there, too. Caffee worked in and did graphic design for many leather businesses. In 1966, he designed the logo for Febe's and created a statue that came to symbolize the bar.

Original Febe's statue of the "Leather David" by Mike Caffee

He modified a small plaster reproduction of Michelangelo's David, making him into a classic 1960s gay biker: "I broke off the raised left arm and lowered it so his thumb could go in his pants pocket, giving him cruiser body language. The biker uniform was constructed of layers of wet plaster. . . . The folds and details of the clothing were carved, undercutting deeply so that the jacket would hang away from his body, exposing his well-developed chest. The pants were button Levis, worn over the boots, and he sported a bulging crotch you couldn't miss. . . . Finally I carved a chain and bike run buttons on his [Harley] cap." (Caffee 1997)

This leather David became one of the best-known symbols of San Francisco leather. The image of the Febe's David appeared on pins, posters, calendars, and matchbooks. It was known and disseminated around the world. The statue itself was reproduced in several formats. Two-foot-tall plaster casts were made and sold by the hundreds. One of the plaster statues currently resides in a leather bar in Boston, having been transported across the country on the back of a motorcycle. Another leather David graces a leather bar in Melbourne, Australia. One is in a case on the wall of the Paradise Lounge, a rock-and-roll bar that opened on the site once occupied by Febe's. Despite its enormous influence, the popularity of the Tool Box was short lived. By 1965, it had competition from the Detour and On the Levee, and by 1966, Febes opened and became the leading leather bar. Although the Tool Box was open until 1971, it was never again the dominant leather bar. However, when the building that housed the Tool Box was torn down for redevelopment in 1971, old patrons came by to get bricks to keep as mementos. During demolition, the wall with the mural was left standing for some time, all alone in a sea of concrete rubble and twisted steel. In his memoir of Chuck Arnett and the Tool Box, Jack Fritscher recalls:

"[T]he Tool Box, long deserted, was torn down by the city for urban renewal. Somehow, though, the wreckers ball failed to knock down the stone wall with Arnett's mural of urban aboriginal men in leather made famous by Life. For two years, at the corner of Fourth and Harrison, drivers coming down the off ramp from the freeway were greeted by Arnett's somber dark shadows, those Lascaux cave drawings of Neanderthal, primal, kick-ass leathermen." (Fritscher 1991, 117118)

The leather scene moved to what would become its Main Street in 1966, when Febe's and the Stud opened up at the western end of Folsom Street. Several other bars soon opened along a three-block strip of Folsom Street, establishing a core area that anchored a burgeoning leather economy with various commercial establishments, which continued to develop and expand in the 1970s to become one of the most extensive and densely occupied leather neighborhoods in the world. The area still functions as the local leather capital. As a result, the South of Market acquired a number of nicknames, including the Folsom, the Miracle Mile, and the Valley of the Kings. This last appellation was coined by local leather columnist Mr. Marcus. By the late 1970s, Mr. Marcus had given each of San Francisco's three major gay neighborhoods a nickname. The Valley of the Kings conveyed an image of powerful, cocky, independent, and sexy masculinity. It contrasted with Marcus' nickname for Polk Street, the Valley of the Queens, in reference to the older and sometimes more effeminate population of gay men associated with the area. He dubbed the Castro the Valley of the Dolls, an allusion to its hordes of young and beautiful men. By the late 1970s, the Castro was unquestionably the center of local gay politics, but the Folsom had become the sexual center. The same features that made the area attractive to leather bars made it hospitable to other forms of gay sexual commerce. Many of the non-leather gay bathhouses and sex clubs also nestled among the warehouses. Just before the age of AIDS, the South of Market had become symbolically and institutionally associated in the gay male community with sex.

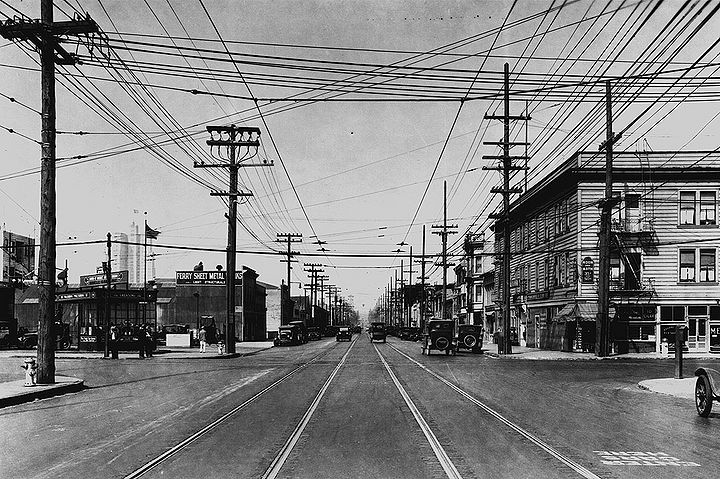

Sixth Street looking southeast across Folsom Street, 1926, long before the neighborhood began to change.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Folsom Street northeast across 6th Street, 1928.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Folsom Street west at 7th Street, 1929.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Folsom Street east at 9th Street, 1927.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Another view from Black Sheets magazine:

Some gay men wanted to assert themselves in masculine, overtly sexual ways, and to find partners who shared their desire for intense sexual connection. Partly, this was in reaction to a society that treated sexuality of almost any type with shame. And certainly part of it was in rejection of a prevailing "one size fits all" effeminate stereotype for gays that did not suit them. Yet it was difficult for these men to find settings where this was not the norm. Once again, many gay men felt isolated this time, in the midst of their own.

Ironically, then, it took the establishment media to part the leather curtain forever. Life magazine's June 26, 1964 feature, "Homosexuality in America," opened with a two-page spread of artist Chuck Arnett's mural towering over the men of San Francisco's Tool Box bar. This moody mural, occasionally enlivened by a smiling face, depicted imposing men in black, all variations on Marlon Brando and James Dean. No doubt many men found in this monument to homomasculinity a mirror against which to measure their own leather style. The Life article was the mass culture's first exposure to gay leather sexuality. Life also called San Francisco the "Gay Capital" of the United States, and the label has certainly stuck. In the 1991 anthology, Leatherfolk, Jack Fritscher described the article as "an image-liberating historical issue that was read across the nation as an invitation to come to San Francisco and be a man's man." It no doubt resulted in some of those frustrated men hitching their wagons to the Folsom's rising star. Go west, young man.

The most famous was Fe-Be's, at 1501 Folsom Street. It was for many years considered the premier gay biker club bar. The upstairs housed the first location of A Taste of Leather, a leather and sex toy shop owned by Nick O'Demus, who resembled a Santa in black leather. A branch of A Taste of Leather eventually opened at Off the Levee, a combination bar and restaurant at 527 Bryant, also founded in 1966. The Stud, at 1535 Folsom, was also initially a leather bar but quickly became a hippie "head" bar.

1968 saw the opening of two South of Market institutions: the Ritch Street Baths at 330 Ritch Street, the poshest of the San Francisco bathhouses, and the Ramrod, the famed leather bar at 1225 Folsom.

Occasionally a leather bar would jump the South of Market border to establish turf in a bordering neighborhood. This was the case with the Sound of Music, in the Tenderloin at 162 Turk, which opened in 1969.

According to Henri Lelue, the owner chose the bar's name so he could put the initials "SM" into the bar sign. The original owner was into rough trade and opened the bar for a kid who was later murdered there. (During the punk era, this became a nightclub showcasing local bands.)

The race to Mecca was on. "Tourists to SFO one summer were residents by the next. Golden Age sex put many a midwestern career in law, medicine, teaching, and business on hold. Man-to-man sex was the siren call," asserts Jack Fritscher in Leatherfolk. "Basically, you had a lot of horny young men, finally unrestrained and turning loose," Jack Fertig agrees. "And it was like, teenage boys without parent figures any more.

They could do whatever the hell they wanted."

--Black Sheets