The Bay Area’s Street Spirit Newspaper: Difference between revisions

m Protected "The Bay Area’s Street Spirit Newspaper" ([edit=sysop] (indefinite) [move=sysop] (indefinite)) |

m bolded abstract text |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | {| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | ||

| colspan="2" |A grassroots, street-distributed, publication called the Street Spirit Newspaper focuses on issues of homelessness in the Bay Area and nation-wide. The Quaker American Friends Service Committee in Oakland founded it in 1995. Street Spirit has played a critical role in the ability to provide homeless and low-income community members with a voice in the Bay Area. Here some background on homelessness in the Bay Area, the history of the newspaper, and personal accounts of vendors are presented. | | colspan="2" |'''A grassroots, street-distributed, publication called the Street Spirit Newspaper focuses on issues of homelessness in the Bay Area and nation-wide. The Quaker American Friends Service Committee in Oakland founded it in 1995. Street Spirit has played a critical role in the ability to provide homeless and low-income community members with a voice in the Bay Area. Here some background on homelessness in the Bay Area, the history of the newspaper, and personal accounts of vendors are presented.''' | ||

|} | |} | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Latest revision as of 19:00, 26 August 2016

Historical Essay

by Lily Kley, 2015

| A grassroots, street-distributed, publication called the Street Spirit Newspaper focuses on issues of homelessness in the Bay Area and nation-wide. The Quaker American Friends Service Committee in Oakland founded it in 1995. Street Spirit has played a critical role in the ability to provide homeless and low-income community members with a voice in the Bay Area. Here some background on homelessness in the Bay Area, the history of the newspaper, and personal accounts of vendors are presented. |

The Birth of Street Spirit

Since the late 1960s, the rise of radical alternative presses and media outlets have played a large role in giving poor people a voice in a political climate where they are almost entirely shut out of major media. (to read more on this anti poor political climate, see the final section of my essay “Historical Context”). The Street News in New York and the Street Sheet in San Francisco – both founded in 1989 - launched the North American street newspaper movement, which quickly spread to many other cities across the nation in the 90’s. Today, 40 publications exist in the United States, and about another 100 in Europe and other parts of the world. (1) These community publications enable contributors and readers to feel a greater sense of collective agency, value and authority; and give the homeless population a democratic public voice.

One of the most powerful alternative publications in the Bay Area is the Street Spirit, a monthly newspaper published by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), which has been giving the homeless population a voice in Berkeley for 20 years. The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker non-profit based in Oakland, decided to provide the public with an alternative story to that told in traditional media outlets AFSC fought to campaign for justice, as it had become clear to them that the corporate-controlled media was heavily biased against homeless people. “The mainstream media often ignored the life-and-death issues faced by homeless people, and when they weren’t ignoring them, the corporate press stereotyped and scapegoated homeless people”. (2)

In early 1995, Sally Hindman, an Oakland-based homeless activist and Quaker, approached the AFSC with the idea of creating a homeless newspaper to serve the cities of Berkeley and Oakland. She approached Terry Messman, a journalism major and long time civil disobedience activist who stood up for those less advantaged, whether he would want to take the lead and become the editor of the publication. He agreed and twenty years later Terry Messman remains as editor and publisher of the newspaper. The publication is as active as ever today, with a new edition published monthly.

The first publication was issued in March 1995, with much fanfare. The Street Spirit is published once a month. The aim was to uncover injustices against the homeless population in Alameda Country and around the nation, as well as introduce and discuss other issues of concern. Reporting from the “shelters, back alleys, soup kitchen lines and slum hotels where mainstream reporters rarely or never visit”, the newspaper passionately covers stories on economic justice, poverty, and the human rights of the poorest of the poor. (3) Articles cover city measures, which aim to criminalize homelessness, local protests, and aim to raise exposure of the everyday struggles of the homeless. All writers, artists, and photographers are unpaid volunteers, who generously contribute their passion and eloquence to the newspaper and enable the newspaper’s existence.

As a recent example, the May 2015 issue reported on protestors who rallied to condemn the anti-homeless laws in Berkeley. (4) Articles advocate for the end of homeless criminalization, by enlightening readers with analyses of studies which for example show that law enforcement and jail time are about two to three times as expensive as the cost of supportive housing, and by including interviews of the homeless who have suffered dehumanization at the hands of the police.

Yet the Street Spirit does not only cover grim stories of poverty. It publishes poems and haikus, and inspiring stories by those that are helping the homeless, for example with the column“Stories from the Suitcase Clinic” and the “Justice” column. The paper galvanizes the social movements around human rights, challenging inequality and raises the hope that accomplishing change is possible. Month after month, the Street Spirit exposes the reality of structural violence and the consequences of poverty, the campaigns, which are challenging this, and fighting for change. In this process it has been instrumental in numerous victories of progressive change.

Street Spirit Collection

Photo: Lily Kley

Street Spirit's Impact

The Street Spirit’s reporting has been responsible for altering the public’s opinion on important homelessness issues. One such victory, which the Street Spirit contributed to, was shutting down the East Bay Hospital in Richmond in 1997, which was known for its psychiatric and human rights abuses. The psychiatric hospital had crammed disabled clients into overcrowded wards in pursuit of higher profit margins. This facility was known for “a record of medical neglect, patients’ rights violations, and the cruel over-use of restraints on its poor, disabled and homeless clients.” (5) For years, the mainstream press failed to report on these conditions. In response to this, the Street Spirit began a 16- part series investigating the mistreatment of these homeless clients, including several suspicious deaths, which occurred at the hospital. In response to this, Bay Area groups launched their own investigations and finally the mainstream press also began to cover this story as well. The Street Spirit’s investigations, which spoke on behalf of those voiceless and silenced victims, helped spark this public outcry, which ultimately led to the closure of this abusive hospital.

Another success story for the homeless population in which the Street Spirit played a large role was the defeat of Measure “S” which aimed to criminalize homelessness in Berkeley in 2012. Measure S, “A Berkeley Sit-Lie Ordinance” was on the ballot in 2012 which would have made it a crime to sit on sidewalks in Berkeley’s commercial districts from 7am to 10pm in all of Alameda County. After a first warning, an initial violation would have carried a $75 fine, with subsequent increasing amounts. The Street Spirit played a large role in the defeat of the measure. (6) The topic was on the front page of the newspaper for seven months straight. Even though the opposition was outspent 20 to one, the voters rejected measure “S”. It was the only electoral ballot measure in recent US history, in about the last 20 years, where voters rejected an anti-homeless measure. This was one of the most prominent victories for the homeless population of Alameda County, and the Street Spirit surely played a role in its success to galvanize support to defeat the measure. (7)

How Street Spirit is Created and Distributed

Today, close to 20,000 people monthly purchase a Street Spirit newspaper, and it is estimated that another 5000 newspapers are passed on and read. (8) More than 150 homeless vendors sell the Street Spirit in Berkeley, Oakland and Santa Cruz. The local vendor program is led by JC Orton, a volunteer, who distributes the papers early in the morning starting at 7:00am, on a daily basis, on Shattuck Ave. downtown Berkeley. The program enables the vendors to interact with others and tell them about the human rights which the homeless also deserve and should have. The program provides jobs and extra earnings to homeless people, and acts as a positive alternative to panhandling. All vendors keep every dollar they earn. For many, this is the only lifeline, which keeps them alive. This equals out to nearly $50,000 per month of direct redistribution exchanging hands every month in the Bay Area.

This is the truck from which JC Orton, a volunteer, distributes the newspapers daily.

Photo: Lily Kley

The Street Spirit provides vendors with a means to get their voice heard and support their cause. I met Paul downtown Shattuck Ave in Berkeley. Paul, a 62 year old retired homeless man, has been selling the paper for about one and a half years. In his younger days he was a music major, and spent years travelling and touring with his band. Two years ago he was diagnosed with lung cancer, which has now reached its second stage, and since then he has been on disability insurance. Paul has been living off of his disability checks, and the extra money earned by the Street Spirit is what keeps him afloat. It is what keeps him fed and enable him to survive, until he gets off the waiting list for public housing. Paul sells the Street Spirit daily, and as he is able to keep all the profits, and he mentioned that this bit of money has saved his life. For him, it’s all about getting out the truth and making people aware of the human rights which all human beings enjoy. He wants all people who read the paper to become more knowledgeable about their rights in this country, and as homeless, especially in light of many injustices which homeless face on the streets. “When I can open one person’s eyes to what’s going on in this country I’ve done my job”. (9) As a postscript, I asked Paul if he would mind if I took his picture but he did not want to have his photograph taken. Later in the day I saw him again, and he had thought twice about this apparently, and said that I could take his picture for a fee of $20.00 yet I did not have my camera on me. I never saw him again.

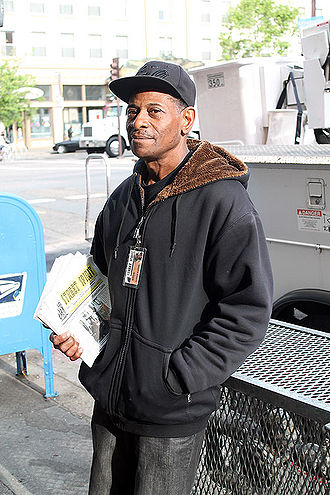

Lindell Waters has been selling the Street Spirit for about two and a half years. Originally from Oakland, he was in jail some time, before starting to work in the construction industry. Now he is 60 and it is difficult for him to find a job. Lindell was one of the lucky ones who was able to receive government subsidized housing quickly, which is what he lives on now. For Lindell, having the opportunity to sell the paper, gives him something to do and is what “keeps him out of trouble and off the streets”. (10) Lindell enjoys being outside and interacting with other people while he is selling the paper, “people know me and look out for me”. (11) He sells the paper five days a week, and makes about $50-$60 a day. As he does not have to pay for his rent, for Lindell this extra income enables him to pay for things like food, his cell phone bill, and other necessities.

Lindell Waters selling issues of the Street Spirit

Photo:Lily Kley

The Political Creation of Rising Homelessness in the SF Bay Area

Homelessness has become a major social and political problem in the USA since the late 1970s. The extent of the problem is especially visible when we consider the situation in Alameda County – a county that by many measurements is progressive. Today, approximately 4,262 people are homeless in Alameda County alone, according to EveryOne Home. The County’s total population is 1.57 million people.

Government policies exacerbated poverty and homelessness in the 1970’s and 1980’s through a decrease in funding for social programs and public housing. It is around this time that San Francisco, and the Bay Area in general, witnessed a dramatic increase in homelessness. Starting in the 70’s, under president Nixon, a drastic shift towards neoliberal market oriented policy took place, which created an increase of poverty and homelessness. Around the late 1960’s, 14% of the children lived in poverty in the United States. Since then, this number has steadily increased, with about 22% of children in the U.S. living under conditions of poverty today. 12 This stark increase of poverty and homelessness in the past decades can be witnessed today. “When I first came to Berkeley in the late ‘40s…there were no homeless people on the streets at all”, said Shirley Dean, a former City Council member for the city of Berkeley. (13) Berkeley, as other cities across the nation, witnessed their homeless population increase dramatically in recent decades.

Nixon changed the way grants for social programs were issued, turning them from categorical grants to block grants, which are more broadly defined and give local governments more discretion as to how best allocate this money. By doing this, Nixon established the political context for a far more aggressive implementation of federal funding cuts, which were later instituted by Reagan. (14)

In the 80’s, during the “Reagan Revolution”, major reductions in federal funding for a wide range of social programs took place. “Republican political strategists used this attack on urban programs to exploit mounting white racial resentment over Kennedy-Johnson era social programs that were perceived by many white Americans as being unduly biased toward central city, predominately black (“underserving” constituents)”. (15) Due to a decrease in funds, local governments were no longer able to allocate resources for urban employment and job training and housing.

Cuts in social programs since the 1970’s had a harsh impact on those with mental health problems, and drug and alcohol addictions, who are commonly ‘at risk’ populations for becoming homeless. Mental health spending decreased by 30%, and many mental health services were closed, as localities did not create community support systems. (16) This left thousands of mentally ill on the streets.

Decreases in Housing: In addition to a decrease in public spending, public housing disappeared, as local governments focused on urban renewal, taking advantage of disinvested areas, which were seen as being suitable for private redevelopment. Emphasis was placed on private-public partnerships in an effort to expand the local tax base. Local government wanted to create a favorable climate to attract corporate business interests, and offered investors “…(a) mix of land write-downs at below-market prices…favorable rezoning amendments, selective tax exemptions, and public absorption of the costs of site assemblage, land clearance…”. (17) There was an overreliance on the private sector to drive urban development and public housing. The needs of the residents did not match up with the profit-motivated interests of those driving urban development.

Housing rents have risen and turned the Bay Area into one of the most expensive housing markets in the nation. Today, market rent in Oakland is $977 above the national average and has been rising sharply in the past year. (18) Someone earning minimum wage would have to work 163 hours a week in Oakland in order to afford the median monthly rent of $2412. (19) Such drastic rent increases make it unaffordable for people to afford a living working full-time at a minimum wage job.

Punitive Measures and Media Portryal: Simultaneous to the policies outlined above, there was a concurrent rise in “law and order” politics, as championed by Nixon and Reagan. Governments at the local, state and national level have spent the past 40 years imposing ever stricter criminal sentences on U.S. citizens, contributing to the fact that the United States incarcerates a greater percentage of its population than any other country in the world. (20) Instead of people receiving the homeless with a caring and open heart, the homeless were handled with punitive measures. Cities started enacting anti-homeless laws and cities across the Bay area began following suit. Homelessness was seen as an individual problem, as “bad behavior”. The “Matrix Program” in San Francisco started distributing thousands of tickets to homeless, ranging up to $180, for acts such as sitting on sidewalks. (21)

The media portrayed homelessness in a critical light. “The institutions who were telling the story of homelessness in the press were conservative organs like the Oakland Tribune…and San Francisco Chronicle…most anti-homeless organizations…were against homeless and against evictions, and they to this day have crusaded for laws which criminalize homeless people”. (22) The corporate press routinely ignored protests and suppressed activist news. The corporate-minded press pushed the narrative that the homeless should be removed out of sight and off the streets.

Its within this context and against this historical backdrop that Street Spirit contributes to the struggle against systemic poverty.

Notes

1. Messman, Terry. "About Street Spirit." The Street Spirit, 24 June 2011. Web.

13 May 2015.

2. Ibid.

3. Butigan, Ken: “Getting the Story Out- Terry Messman and the power of activist journalism"

Waging Non Violence: People-Powered News and Analysis. January 24, 2013.

4.Denmey, Carol: “DBA Paints a Happy Face Over a Brutal Beatdown” The Street Spirit, May

2015; Volume 21, No. 5

5. Messman, Terry. "East Bay Hospital Is Closed for Good." The Street Spirit. N.p., 01 Aug.

1997. Web. 13 May 2015.

6. "Berkeley Sit-Lie Ordinance, Measure S (November 2012)." Ballotpedia.com, 2011. Web. 13 May 2015.

7. Interview with Terry Messman by author, April 17, 2015.

8. Ibid

9. Interview with Paul by author, May 8, 2015.

10. Interview with Lindell Waters by author, May 14, 3015

11. Ibid

12. Desilver, Drew. "Who’s Poor in America? 50 Years into the ‘War on Poverty,’ a Data Portrait." Pew Research Center RSS. N.p., 13 Jan. 2014. Web. 13 May 2015.

13. Chen, Daphne. "Federal Policy Changes Contribute to Rise in Local Homeless Population Homelessness in Berkeley - The Daily Californian." The Daily Californian. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 May 2015.

14. Beitel, Karl: “Local Protests, Global Movements: Capital, Community, and State in San

Francisco” Temple University Press; 2013 pg. 11

15. Ibid, p. 13

16. Chen, Daphne. "Federal Policy Changes Contribute to Rise in Local Homeless Population Homelessness in Berkeley - The Daily Californian." The Daily Californian. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 May 2015.

17. "San Francisco." American Bar Association Journal 58.7 (1972): 715-23. Temple University Press. Web. 15 May 2015.

18. Key Findings and Policy Implications." TALIS Teaching Practices and Pedagogical

Innovations (2013): 111-24. Everyone Home. From the 2013 Alameda Countywide Homeless Count and Survey Report.

19. Dawn Philips: “Planning For People, Not for Profiteers,” The Street Spirit, May 2015

20. Newell, Walker. "The Legacy of Nixon, Reagan, and Horton: How the Tough on Crime Movement Enabled a New Regime of Race – Influenced Employment Discrimination.” 2013. Berkeley Journal of African-American Law and Policy

21.Gowan, Teresa: “Hobos, Hustlers, and Backsliders: Homelessness in San Francisco”; University of Minnesota Press, 2010, pg. 243

22. Interview with Terry Messman by author, April 17, 2015.