Poverty, Social Isolation, Transsexuality: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

The local San Francisco Equal Opportunity Council was responsible for allocating the monies flowing to San Francisco from President Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 War on Poverty. Originally millions were targeted at four neighborhoods, defined based on ethnicity and historic discrimination and impoverishment: Chinatown, the Mission, the Fillmore/Western Addition, and Bayview/Hunter’s Point. The Tenderloin was only added after two years of organizing and agitation by neighborhood residents and organizers from area churches and social service agencies. | The local San Francisco Equal Opportunity Council was responsible for allocating the monies flowing to San Francisco from President Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 War on Poverty. Originally millions were targeted at four neighborhoods, defined based on ethnicity and historic discrimination and impoverishment: Chinatown, the Mission, the Fillmore/Western Addition, and Bayview/Hunter’s Point. The Tenderloin was only added after two years of organizing and agitation by neighborhood residents and organizers from area churches and social service agencies. | ||

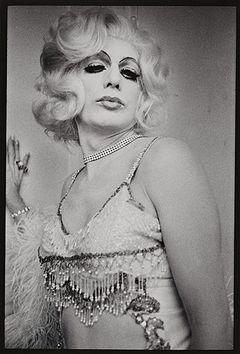

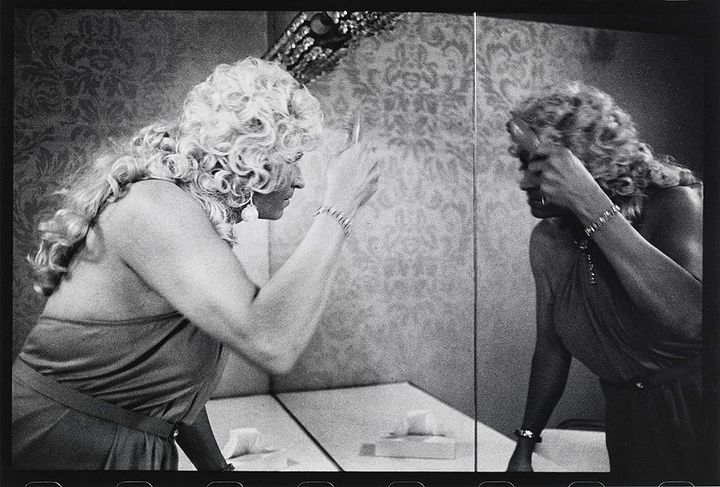

'''Drag Queens of the 1960s and 1970s''' | '''Drag Queens of the 1960s and 1970s''' | ||

| Line 11: | Line 9: | ||

''Image: Anthony Friedkin'' | ''Image: Anthony Friedkin'' | ||

The Tenderloin effort, which brought federal relief to the “Central City Target Area” (also including blocks south of Market in addition to the contemporary Tenderloin district), was path-breaking for the entire country in redefining the what was understood as “disadvantaged,” and thus eligible for federal anti-poverty support. The new Central City Target Area was largely inhabited in the mid-1960s by poor white residents, many of whom were homosexuals, impoverished elderly, abusers of drugs and alcohol, and young runaways and cast-outs. The social stigma attached to these “categories” (which largely derived from a sense that individual moral turpitude or personal failure was responsible) had made this poor population harder to include in public anti-poverty support. | [[Image:The-Gay-Essay-Drag-Queen-1960s-1970s-Black-and-White-Photography-01-694x1024.jpg|240px|left]] | ||

The Tenderloin effort, which brought federal relief to the “Central City Target Area” (also including blocks south of Market in addition to the contemporary Tenderloin district), was path-breaking for the entire country in redefining the what was understood as “disadvantaged,” and thus eligible for federal anti-poverty support. The new Central City Target Area was largely inhabited in the mid-1960s by poor white residents, many of whom were homosexuals, impoverished elderly, abusers of drugs and alcohol, and young runaways and cast-outs. The social stigma attached to these “categories” (which largely derived from a sense that individual moral turpitude or personal failure was responsible) had made this poor population harder to include in public anti-poverty support. | |||

But, as Martin Meeker has shown, a “coalition of liberal ministers, gay activists, and Central City residents worked together to produce a new poverty knowledge focused less on racial discrimination and cross-generational poverty, but much more on social isolation and its causes.” The Central City Target Area was the first time homosexuals (and others at the margins of mainstream acceptability) received benefits from the welfare state based on their different ''way of being''. Moreover, with this new sense of entitlement came a growing awareness of a shared identity, and with it a growing commitment to dignity and basic civil rights—the foundation of today’s widely accepted LGBT movement. The 1960s Tenderloin activists didn’t try to minimize the role of race in defining poverty, but argued that social marginalization and individual isolation were also key factors, thus augmenting the mix of economic and ethno-racial factors already in play. | But, as Martin Meeker has shown, a “coalition of liberal ministers, gay activists, and Central City residents worked together to produce a new poverty knowledge focused less on racial discrimination and cross-generational poverty, but much more on social isolation and its causes.” The Central City Target Area was the first time homosexuals (and others at the margins of mainstream acceptability) received benefits from the welfare state based on their different ''way of being''. Moreover, with this new sense of entitlement came a growing awareness of a shared identity, and with it a growing commitment to dignity and basic civil rights—the foundation of today’s widely accepted LGBT movement. The 1960s Tenderloin activists didn’t try to minimize the role of race in defining poverty, but argued that social marginalization and individual isolation were also key factors, thus augmenting the mix of economic and ethno-racial factors already in play. | ||

Revision as of 14:47, 20 May 2017

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

The local San Francisco Equal Opportunity Council was responsible for allocating the monies flowing to San Francisco from President Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 War on Poverty. Originally millions were targeted at four neighborhoods, defined based on ethnicity and historic discrimination and impoverishment: Chinatown, the Mission, the Fillmore/Western Addition, and Bayview/Hunter’s Point. The Tenderloin was only added after two years of organizing and agitation by neighborhood residents and organizers from area churches and social service agencies.

Drag Queens of the 1960s and 1970s

Image: Anthony Friedkin

The Tenderloin effort, which brought federal relief to the “Central City Target Area” (also including blocks south of Market in addition to the contemporary Tenderloin district), was path-breaking for the entire country in redefining the what was understood as “disadvantaged,” and thus eligible for federal anti-poverty support. The new Central City Target Area was largely inhabited in the mid-1960s by poor white residents, many of whom were homosexuals, impoverished elderly, abusers of drugs and alcohol, and young runaways and cast-outs. The social stigma attached to these “categories” (which largely derived from a sense that individual moral turpitude or personal failure was responsible) had made this poor population harder to include in public anti-poverty support.

But, as Martin Meeker has shown, a “coalition of liberal ministers, gay activists, and Central City residents worked together to produce a new poverty knowledge focused less on racial discrimination and cross-generational poverty, but much more on social isolation and its causes.” The Central City Target Area was the first time homosexuals (and others at the margins of mainstream acceptability) received benefits from the welfare state based on their different way of being. Moreover, with this new sense of entitlement came a growing awareness of a shared identity, and with it a growing commitment to dignity and basic civil rights—the foundation of today’s widely accepted LGBT movement. The 1960s Tenderloin activists didn’t try to minimize the role of race in defining poverty, but argued that social marginalization and individual isolation were also key factors, thus augmenting the mix of economic and ethno-racial factors already in play.

As it happens, this was contemporaneous to the rebirth of Glide Methodist Church and the entry of Rev. Ted McIlvenna to Glide and the Tenderloin. He recognized the population in his new neighborhood, began a Young Adult Project, reached out to the only public homosexual organizations at that time, the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, and by July 1964, participated in the founding of the Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH). Phyllis Lyon of the DOB also became McIlvenna’s secretary during this period.

Drag Queens of the 1960s-1970s.

Image: Anthony Friedkin

Transsexuality came of age in the Tenderloin in the mid-1960s too, arising from the confluence of gay organizing, anti-poverty claims on behalf of the isolated and socially marginalized “deviant” characters in the Tenderloin, and the emergence of a medical approach to changing gender. The new ideas about gender started with the famous Christine Jorgensen sex-change operation in 1952, but by the mid-1960s was entering more widespread acceptance due to the work of Dr. Harry Benjamin and other clinically trained professionals—Benjamin’s 1966 publication of The Transsexual Phenomenon was the first book-length treatment of transsexuality and helped create a new orthodoxy in medical and psychotherapeutic circles. Dr. Benjamin ran his summer practice from an office off Union Square, just blocks from the thriving gay drag (“queen”) scene on Turk Street that included El Rosa, Sound of Music, Chukkers, the Camelot, and the Hilliard, along with other establishments in the surrounding streets.

In August 1966 the now-famous mini-riot at Compton’s Cafeteria on Taylor and Turk took place. Police rolled in to carry out what had been routine roustings and mass arrests of queens and gays, but for the first time the patrons of Comptons fought back, smashing windows and fighting the police with shoes and handbags in the streets. Early historians of San Francisco’s gay community wrote in 1998 that “the Tenderloin’s legacy of transgender militancy contributed significantly to early gay liberation efforts in San Francisco,” leading to the establishment later of the Gay Liberation Front, which evolved into the Gay Activist Alliance, which founded the Helping Hands Center on Turk Street to provide support and services for transsexuals as part of its overall mission.