Winemaking in the Bayview: Difference between revisions

m (moved Bayshore and Alemany 1935 to Winemaking in the Bayview) |

m (Protected "Winemaking in the Bayview" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite))) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

''By Ruth Eshow Upton'' | ''By Ruth Eshow Upton'' | ||

Early in the Fall the men in our neighborhood made wine. It was the only time that the fathers of our playmates socialized together. The Bayview District in the | Early in the Fall the men in our neighborhood made wine. It was the only time that the fathers of our playmates socialized together. The Bayview District in the 1920s and 1930s was comprised of immigrants of differing nationalities who, as soon as they were able, bought houses in this semi-rural area where they could raise healthy children and grow flowers and fruit trees. They all worked hard and preferred to spend their limited leisure time with their families and their countrymen. Not that they were clannish, as I heard them described by monolingual Americans. It is that in their own language they could be witty and amusing as opposed to heavy and polite in a language they were in the process of learning. Our mothers made friends because of their common interest as homemakers. They assembled on the street when the Genovese truck farmers came around with their fresh produce. They joined to pick watercress that grew in the swampy ditch down the street. After the rains they looked for mushrooms that grew on Black Hill, above Candlestick Cove. And they all belonged to the Bret Harte Grammar School PTA. | ||

[[Image:San-Bruno-and-Silver-1927-AAB-5240.jpg]] | [[Image:San-Bruno-and-Silver-1927-AAB-5240.jpg]] | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

In September there was a change. The fathers got together to schedule the winemaking. One man owned or rented the crusher which he then rented to the winemakers. Each man fixed a date to use it. The grapes were ordered to be delivered the day before the crusher’s use. No one warned me when it was my father’s turn. It was a shock to find lugs of Thompson | In September there was a change. The fathers got together to schedule the winemaking. One man owned or rented the crusher which he then rented to the winemakers. Each man fixed a date to use it. The grapes were ordered to be delivered the day before the crusher’s use. No one warned me when it was my father’s turn. It was a shock to find lugs of Thompson seedless grapes lined up on our driveway on coming home from school. An unpleasant odor of overripe grapes filled the air; tiny fruit flies hovered over them. I knew that life would be topsy-turvy for the next few days. The house would seem empty without my mother in the warm kitchen. Absent were the familiar fragrances emanating from pots simmering on the top of the stove or the aroma of bread baking in the oven. My mother was outside hauling the boxes of grapes to my father, who emptied them into the crusher. At a dollar a day for its rental and with others waiting, he had to work fast. After the press, he transferred the juice to the vat that occupied a corner of our garage. When the grapes had turned into wine he filled the bottles, corked them and stored them in the small wine cellar he’d built. My father was enormously proud of the output, a dry golden liquor that we all admired. | ||

Next came wine tasting. The men made the rounds, sampling each other’s wine. Mr. Zarosi, our next-door neighbor, a Romanian, made red wine from Muscat grapes, I think. Each year, after the tasting, my father sniffed, “Zarosi must have put a sack of sugar in his wine!” (This remark stayed with me | Next came wine tasting. The men made the rounds, sampling each other’s wine. Mr. Zarosi, our next-door neighbor, a Romanian, made red wine from Muscat grapes, I think. Each year, after the tasting, my father sniffed, “Zarosi must have put a sack of sugar in his wine!” (This remark stayed with me so that I have always chosen wines labeled “sec.”) | ||

[[Image:San-Bruno-Avenue-1928-AAB-5243.jpg]] | [[Image:San-Bruno-Avenue-1928-AAB-5243.jpg]] | ||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | ||

Then came visits from his countrymen from other parts of the city. Three or four arrived together. After the salutations in Assyrian—“Shlamalokh, babit yimi!”—they descended to the wine cellar where they admired the collection and tasted the wine.( One afternoon three-year old Lily wandered down to join them. They must have given her a sip of wine because when she came back into our kitchen-dining room she wove around, laughing and acting silly. She crawled under the round oak dining table and had to be coaxed out.) In a little while they came upstairs, jovial, talkative, and settled themselves around the big, round oak table. We children cleared out but we could hear them clinking their glasses after the toast, “Dahksoon.” | Then came visits from his countrymen from other parts of the city. Three or four arrived together. After the salutations in Assyrian—“Shlamalokh, babit yimi!”—they descended to the wine cellar where they admired the collection and tasted the wine. (One afternoon three-year old Lily wandered down to join them. They must have given her a sip of wine because when she came back into our kitchen-dining room she wove around, laughing and acting silly. She crawled under the round oak dining table and had to be coaxed out.) In a little while they came upstairs, jovial, talkative, and settled themselves around the big, round oak table. We children cleared out but we could hear them clinking their glasses after the toast, “Dahksoon.” | ||

They reminisced about their youth in Urmia and spoke of going to Baghdad where they would live like princes on the American dollars they were saving. My sisters and I, eavesdropping, were dismayed. Lily, the youngest, burst into tears. “We don’t want to go to Baghdad,” we wailed. My mother soothingly assured us not to worry, no one was going anywhere. They sang songs in Assyrian, Turkish and Kurdish, a hand cupped over the right ear. My father had written all the lyrics in the Aramaic script ion a little black book. Soon they moved to the living room where the Victrola was. They danced in line, flourishing a handkerchief; usually included was the Tanzara, whose music and steps intrigued me | They reminisced about their youth in Urmia and spoke of going to Baghdad where they would live like princes on the American dollars they were saving. My sisters and I, eavesdropping, were dismayed. Lily, the youngest, burst into tears. “We don’t want to go to Baghdad,” we wailed. My mother soothingly assured us not to worry, no one was going anywhere. They sang songs in Assyrian, Turkish, and Kurdish, a hand cupped over the right ear. My father had written all the lyrics in the Aramaic script ion a little black book. Soon they moved to the living room where the Victrola was. They danced in line, flourishing a handkerchief; usually included was the Tanzara, whose music and steps intrigued me. | ||

When the men departed, they were in a in a happy mood, each carrying a bottle of my father’s wine. | When the men departed, they were in a in a happy mood, each carrying a bottle of my father’s wine. | ||

As my mother predicted, no one went to Baghdad. Instead, they moved to the San Joaquin Valley town of Turlock where there was a growing colony of Assyrians from Lake Urrmia in Persia. They had found the humid climate perfect for raising sweet melons; they thrived, their children grew up as Americans | As my mother predicted, no one went to Baghdad. Instead, they moved to the San Joaquin Valley town of Turlock where there was a growing colony of Assyrians from Lake Urrmia in Persia. They had found the humid climate perfect for raising sweet melons; they thrived, their children grew up as Americans. After my father died, his friends came to the house to offer condolences. One timidly asked my mother for the book of lyrics; she gave it to him gladly. | ||

When we packed to move from Le Conte Avenue to the Richmond District in 1939 we came across one bottle of wine. Its golden liquid gleamed clearly through the glass. We never opened it. I don’t know whatever became of it. | When we packed to move from Le Conte Avenue to the Richmond District in 1939 we came across one bottle of wine. Its golden liquid gleamed clearly through the glass. We never opened it. I don’t know whatever became of it. | ||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

'''Southerly view of Bayshore Boulevard and Alemany Boulevard intersection, c. 1935''' | '''Southerly view of Bayshore Boulevard and Alemany Boulevard intersection, c. 1935''' | ||

''Photo: | ''Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA'' | ||

[[Bayshore Blvd with Potrero Hill |Prev. Document]] [[Islais Creek Remembered |Next Document]] | [[Bayshore Blvd with Potrero Hill |Prev. Document]] [[Islais Creek Remembered |Next Document]] | ||

[[category:Bayview/Hunter's Point]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:Italian]] [[category:Greek]] [[category:Portola]] | [[category:Bayview/Hunter's Point]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:Italian]] [[category:Greek]] [[category:Portola]] | ||

Latest revision as of 04:22, 10 September 2017

"I was there..."

By Ruth Eshow Upton

Early in the Fall the men in our neighborhood made wine. It was the only time that the fathers of our playmates socialized together. The Bayview District in the 1920s and 1930s was comprised of immigrants of differing nationalities who, as soon as they were able, bought houses in this semi-rural area where they could raise healthy children and grow flowers and fruit trees. They all worked hard and preferred to spend their limited leisure time with their families and their countrymen. Not that they were clannish, as I heard them described by monolingual Americans. It is that in their own language they could be witty and amusing as opposed to heavy and polite in a language they were in the process of learning. Our mothers made friends because of their common interest as homemakers. They assembled on the street when the Genovese truck farmers came around with their fresh produce. They joined to pick watercress that grew in the swampy ditch down the street. After the rains they looked for mushrooms that grew on Black Hill, above Candlestick Cove. And they all belonged to the Bret Harte Grammar School PTA.

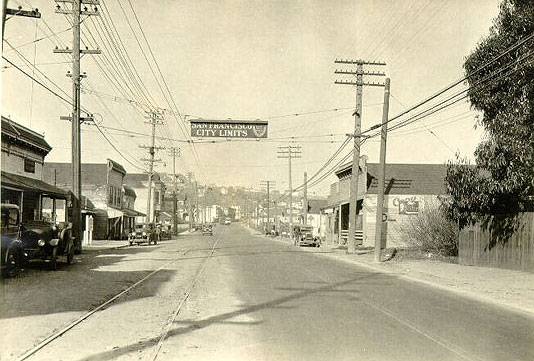

San Bruno and Silver Avenues, 1927.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

In September there was a change. The fathers got together to schedule the winemaking. One man owned or rented the crusher which he then rented to the winemakers. Each man fixed a date to use it. The grapes were ordered to be delivered the day before the crusher’s use. No one warned me when it was my father’s turn. It was a shock to find lugs of Thompson seedless grapes lined up on our driveway on coming home from school. An unpleasant odor of overripe grapes filled the air; tiny fruit flies hovered over them. I knew that life would be topsy-turvy for the next few days. The house would seem empty without my mother in the warm kitchen. Absent were the familiar fragrances emanating from pots simmering on the top of the stove or the aroma of bread baking in the oven. My mother was outside hauling the boxes of grapes to my father, who emptied them into the crusher. At a dollar a day for its rental and with others waiting, he had to work fast. After the press, he transferred the juice to the vat that occupied a corner of our garage. When the grapes had turned into wine he filled the bottles, corked them and stored them in the small wine cellar he’d built. My father was enormously proud of the output, a dry golden liquor that we all admired.

Next came wine tasting. The men made the rounds, sampling each other’s wine. Mr. Zarosi, our next-door neighbor, a Romanian, made red wine from Muscat grapes, I think. Each year, after the tasting, my father sniffed, “Zarosi must have put a sack of sugar in his wine!” (This remark stayed with me so that I have always chosen wines labeled “sec.”)

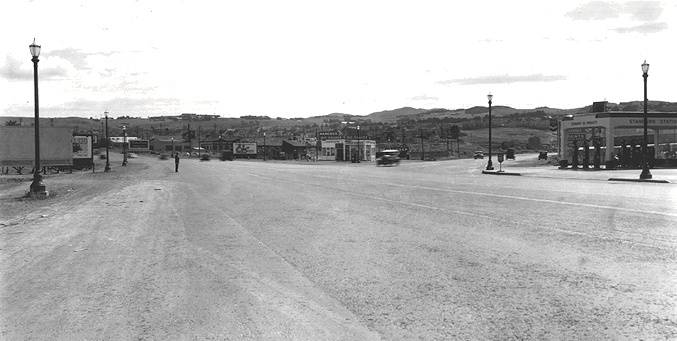

San Bruno Avenue near city limits, 1928.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Then came visits from his countrymen from other parts of the city. Three or four arrived together. After the salutations in Assyrian—“Shlamalokh, babit yimi!”—they descended to the wine cellar where they admired the collection and tasted the wine. (One afternoon three-year old Lily wandered down to join them. They must have given her a sip of wine because when she came back into our kitchen-dining room she wove around, laughing and acting silly. She crawled under the round oak dining table and had to be coaxed out.) In a little while they came upstairs, jovial, talkative, and settled themselves around the big, round oak table. We children cleared out but we could hear them clinking their glasses after the toast, “Dahksoon.”

They reminisced about their youth in Urmia and spoke of going to Baghdad where they would live like princes on the American dollars they were saving. My sisters and I, eavesdropping, were dismayed. Lily, the youngest, burst into tears. “We don’t want to go to Baghdad,” we wailed. My mother soothingly assured us not to worry, no one was going anywhere. They sang songs in Assyrian, Turkish, and Kurdish, a hand cupped over the right ear. My father had written all the lyrics in the Aramaic script ion a little black book. Soon they moved to the living room where the Victrola was. They danced in line, flourishing a handkerchief; usually included was the Tanzara, whose music and steps intrigued me.

When the men departed, they were in a in a happy mood, each carrying a bottle of my father’s wine.

As my mother predicted, no one went to Baghdad. Instead, they moved to the San Joaquin Valley town of Turlock where there was a growing colony of Assyrians from Lake Urrmia in Persia. They had found the humid climate perfect for raising sweet melons; they thrived, their children grew up as Americans. After my father died, his friends came to the house to offer condolences. One timidly asked my mother for the book of lyrics; she gave it to him gladly.

When we packed to move from Le Conte Avenue to the Richmond District in 1939 we came across one bottle of wine. Its golden liquid gleamed clearly through the glass. We never opened it. I don’t know whatever became of it.

Southerly view of Bayshore Boulevard and Alemany Boulevard intersection, c. 1935

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco, CA