Eggers: Difference between revisions

m (PC) |

(added new photos) |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

''Photo: California Academy of Sciences Special Collections '' | ''Photo: California Academy of Sciences Special Collections '' | ||

The California murre (''Uria aalge californica'') lays a large and delicious egg which was a staple of the coastal north American diet long before the introduction of the domesticated chicken. The murre nested by the hundreds of thousands on the Farallon islands off the San Francisco coast. That is, until the popularity of 'egging'. | The California murre (''Uria aalge californica'') lays a large and delicious egg which was a staple of the coastal north American diet long before the introduction of the domesticated chicken. The murre nested by the hundreds of thousands on the [[Farallones Islands 1874|Farallon islands]] off the San Francisco coast. That is, until the popularity of 'egging'. | ||

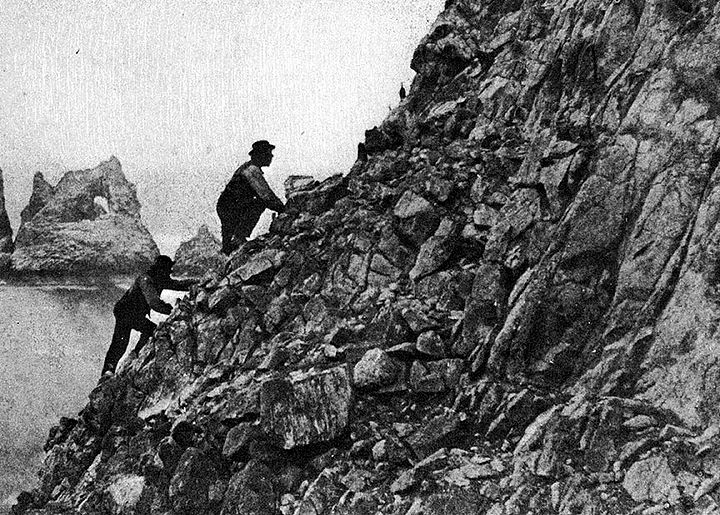

[[Image:Eggers-on-farallones.jpg|720px]] | |||

'''Gathering sea bird eggs at the Farallones.''' | |||

''Photo: Bancroft Library'' | |||

The first extended human habitation of the Farallones began with the establishment of Fort Ross, set up to supply Russian colonists in Alaska. From 1812 to 1838 they took tens of thousands of eggs and killed thousands of the birds as well as seals. | The first extended human habitation of the Farallones began with the establishment of Fort Ross, set up to supply Russian colonists in Alaska. From 1812 to 1838 they took tens of thousands of eggs and killed thousands of the birds as well as seals. | ||

[[Image:Farallon-Island-govt-post 5391.jpg]] | |||

'''Human inhabitation on the Farallones is now limited to scientists working on authorized projects in this 2007 photo.''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | |||

In 1848 aspiring theater entrepreneur David "Doc" Robinson, leery of the hazards of gold prospecting, decided to seek his fortunes in eggs. With his brother in law in a rented whaling boat, Robinson set sail for the Farallones. Although he lost half his take in a squall, he returned to San Francisco with $3,000 worth of murre eggs, enough to found his Dramatic Museum theater. | In 1848 aspiring theater entrepreneur David "Doc" Robinson, leery of the hazards of gold prospecting, decided to seek his fortunes in eggs. With his brother in law in a rented whaling boat, Robinson set sail for the Farallones. Although he lost half his take in a squall, he returned to San Francisco with $3,000 worth of murre eggs, enough to found his Dramatic Museum theater. | ||

Robinson's daring exploit touched off a frenzy for egging. Daredevil riggers and climbers scurried over the island in search of their golden eggs. | Robinson's daring exploit touched off a frenzy for egging. Daredevil riggers and climbers scurried over the island in search of their golden eggs. | ||

[[Image:Farallones-sun-and-ocean 5377.jpg]] | |||

'''Farallones Islands from the northwest, 2007, showing how treacherous and difficult accessing the islands can be.''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | |||

By 1850, a group of eggers launched the Farallon Egg Company (also known as the Pacific Egg Company). They set out to acquire complete rights to all the eggs of the Farallones. Around the same time the U.S. government decided to build a state-of-the-art lighthouse on the Farallones to guide the thousands of ships that were now streaming into San Francisco Bay. The most powerful Fresnel light available was ordered from France. | By 1850, a group of eggers launched the Farallon Egg Company (also known as the Pacific Egg Company). They set out to acquire complete rights to all the eggs of the Farallones. Around the same time the U.S. government decided to build a state-of-the-art lighthouse on the Farallones to guide the thousands of ships that were now streaming into San Francisco Bay. The most powerful Fresnel light available was ordered from France. | ||

By 1855, the lighthouse was fully operational, but there were ongoing, often armed conflicts between the egg company and the lighthouse crews. Independent eggers also continued to challenge the egg company's right to control of the island's eggs. They built a house and occupied a part of the island. There were three small skirmishes with the Navy and a final shoot-out between the company and the free-lancers. The company came out on top of the fight and retained a monopoly over the egg trade for the next eighteen years. | By 1855, the lighthouse was fully operational, but there were ongoing, often armed conflicts between the egg company and the lighthouse crews. Independent eggers also continued to challenge the egg company's right to control of the island's eggs. They built a house and occupied a part of the island. There were three small skirmishes with the Navy and a final shoot-out between the company and the free-lancers. The company came out on top of the fight and retained a monopoly over the egg trade for the next eighteen years. | ||

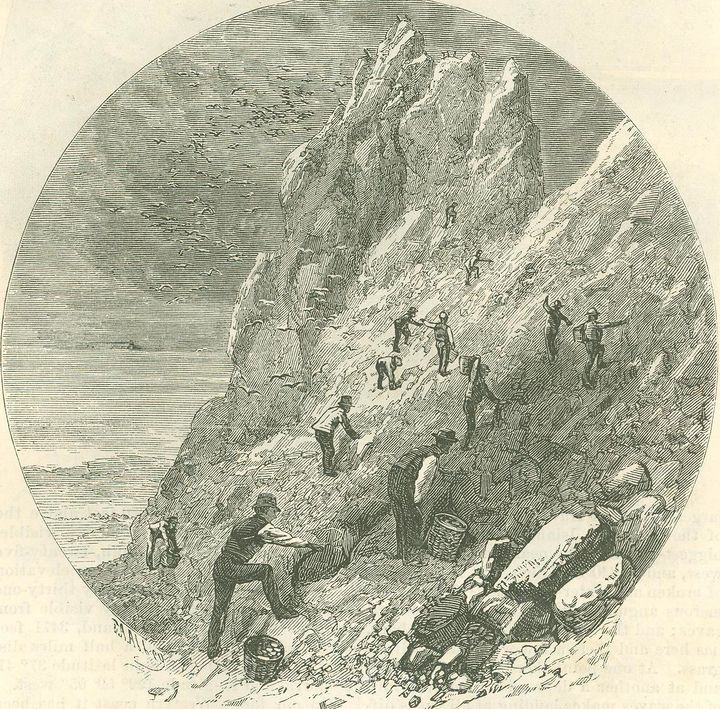

[[Image:Gathering eggs at the Rookeries.jpg|720px]] | |||

'''Gathering eggs at the rookeries on Farallon Island, 1874.''' | |||

''Harper's Magazine'' | |||

Arguments with the lighthouse crews never subsided, and in 1881 U.S. Marshals were called in to evict the egg company for good. When they first started harvesting eggs, they were taking over 900,000 per year; twenty years later that had dropped to 300,000. Independent egging continued into the 1890s, but harvesters were only taking around 150,000 eggs per season. | Arguments with the lighthouse crews never subsided, and in 1881 U.S. Marshals were called in to evict the egg company for good. When they first started harvesting eggs, they were taking over 900,000 per year; twenty years later that had dropped to 300,000. Independent egging continued into the 1890s, but harvesters were only taking around 150,000 eggs per season. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 49: | ||

By this time, the plight of the murres, whose population was only about one fifth what it had been fifty years earlier, came to the attention of Leverett M. Lewis. Lewis was a scientist with the California Academy of Sciences and he began a campaign to stop egging. He was successful in convincing the Lighthouse Board to ban the practice, and for the last hundred years the murres have been living undisturbed. Despite careful protections their population has yet to recover. | By this time, the plight of the murres, whose population was only about one fifth what it had been fifty years earlier, came to the attention of Leverett M. Lewis. Lewis was a scientist with the California Academy of Sciences and he began a campaign to stop egging. He was successful in convincing the Lighthouse Board to ban the practice, and for the last hundred years the murres have been living undisturbed. Despite careful protections their population has yet to recover. | ||

--based on "Robbing a Golden Rookery" by Aleta Brown in ''California WILD'' magazine, Winter 1999 | ''--based on "Robbing a Golden Rookery" by Aleta Brown in ''California WILD'' magazine, Winter 1999'' | ||

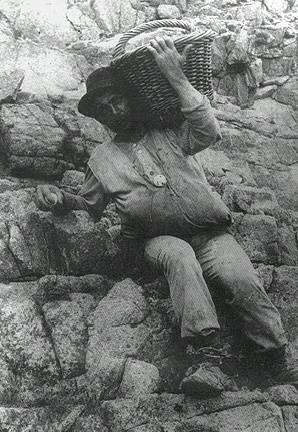

[[Image:outofsf$eggman-with-basket.jpg]] | [[Image:outofsf$eggman-with-basket.jpg]] | ||

| Line 33: | Line 57: | ||

''Photo: California Academy of Sciences Special Collections '' | ''Photo: California Academy of Sciences Special Collections '' | ||

[[Image: | <hr> | ||

[[Image:Tours-food.gif|link=The Farmer with the Golden Plow: John Meirs Horner (1821-1912)]] [[The Farmer with the Golden Plow: John Meirs Horner (1821-1912)| Continue Food Tour]] | |||

[[Treasure Island | [[Treasure Island Views of SF |Prev. Document]] [[San Quentin Prison |Next Document]] | ||

[[category:San Francisco outside the city]] [[category:1776-1823]] [[category:1823-1846]] [[category:1850s]] [[category:Gold Rush]] [[category:1860s]] [[category:food]] [[category:1870s]] [[category:1880s]] [[category:1890s]] | [[category:San Francisco outside the city]] [[category:1776-1823]] [[category:1823-1846]] [[category:1850s]] [[category:Gold Rush]] [[category:1860s]] [[category:food]] [[category:1870s]] [[category:1880s]] [[category:1890s]] | ||

Latest revision as of 12:46, 26 September 2017

Historical Essay

by Joe Metzler

"Eggers" took nearly a million eggs a year in the early years of San Francisco from the bird-covered Farallones Islands 27 miles west of the Golden Gate.

Photo: California Academy of Sciences Special Collections

The California murre (Uria aalge californica) lays a large and delicious egg which was a staple of the coastal north American diet long before the introduction of the domesticated chicken. The murre nested by the hundreds of thousands on the Farallon islands off the San Francisco coast. That is, until the popularity of 'egging'.

Gathering sea bird eggs at the Farallones.

Photo: Bancroft Library

The first extended human habitation of the Farallones began with the establishment of Fort Ross, set up to supply Russian colonists in Alaska. From 1812 to 1838 they took tens of thousands of eggs and killed thousands of the birds as well as seals.

Human inhabitation on the Farallones is now limited to scientists working on authorized projects in this 2007 photo.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

In 1848 aspiring theater entrepreneur David "Doc" Robinson, leery of the hazards of gold prospecting, decided to seek his fortunes in eggs. With his brother in law in a rented whaling boat, Robinson set sail for the Farallones. Although he lost half his take in a squall, he returned to San Francisco with $3,000 worth of murre eggs, enough to found his Dramatic Museum theater.

Robinson's daring exploit touched off a frenzy for egging. Daredevil riggers and climbers scurried over the island in search of their golden eggs.

Farallones Islands from the northwest, 2007, showing how treacherous and difficult accessing the islands can be.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

By 1850, a group of eggers launched the Farallon Egg Company (also known as the Pacific Egg Company). They set out to acquire complete rights to all the eggs of the Farallones. Around the same time the U.S. government decided to build a state-of-the-art lighthouse on the Farallones to guide the thousands of ships that were now streaming into San Francisco Bay. The most powerful Fresnel light available was ordered from France.

By 1855, the lighthouse was fully operational, but there were ongoing, often armed conflicts between the egg company and the lighthouse crews. Independent eggers also continued to challenge the egg company's right to control of the island's eggs. They built a house and occupied a part of the island. There were three small skirmishes with the Navy and a final shoot-out between the company and the free-lancers. The company came out on top of the fight and retained a monopoly over the egg trade for the next eighteen years.

Gathering eggs at the rookeries on Farallon Island, 1874.

Harper's Magazine

Arguments with the lighthouse crews never subsided, and in 1881 U.S. Marshals were called in to evict the egg company for good. When they first started harvesting eggs, they were taking over 900,000 per year; twenty years later that had dropped to 300,000. Independent egging continued into the 1890s, but harvesters were only taking around 150,000 eggs per season.

By this time, the plight of the murres, whose population was only about one fifth what it had been fifty years earlier, came to the attention of Leverett M. Lewis. Lewis was a scientist with the California Academy of Sciences and he began a campaign to stop egging. He was successful in convincing the Lighthouse Board to ban the practice, and for the last hundred years the murres have been living undisturbed. Despite careful protections their population has yet to recover.

--based on "Robbing a Golden Rookery" by Aleta Brown in California WILD magazine, Winter 1999

Eggman with basket on the Farallones.

Photo: California Academy of Sciences Special Collections