1960: A Turning Point: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(changed category) |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

''by Will Roscoe'' | |||

[[Image:gay1$two-castro-couples.jpg]] | [[Image:gay1$two-castro-couples.jpg]] | ||

| Line 4: | Line 8: | ||

''Photo: Crawford Barton, Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California'' | ''Photo: Crawford Barton, Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California'' | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''An intersectional gay rights movement came to light in the 1960s when the gay community joined with the momentum of the civil rights movement, anti-war protestors, and feminists. This communal gay rights movement was prefaced by two events. Firstly, a much-debated “Homosexual Bill of Rights” was drafted and acted as a prototype for the gay civil rights agenda of the 1970s. Secondly, the incumbent mayor Christopher was re-elected in 1959 by a landslide even after the opposing candidate ran a smear campaign criticizing the mayor of harboring “sexual deviates” in the city. There were many new political efforts by the early gay community, including the Tavern Guild, the Society for Individual Rights, and the Council on Religion and Homosexuality, that together helped curb rampant anti-gay police brutality.''' | |||

|} | |||

In the 1960s, the gay movement absorbed the profound and successive influences of the civil rights, anti-war, feminist and counterculture movements. The broad vision of the early [[Mattachine: Radical Roots of the Gay Movement |Mattachine]] was again taken up in civil rights activism and community building efforts. But it took several years for these elements to converge and for a grassroots gay community to adopt a civil rights agenda and burst into the forum of national politics. | In the 1960s, the gay movement absorbed the profound and successive influences of the civil rights, anti-war, feminist and counterculture movements. The broad vision of the early [[Mattachine: Radical Roots of the Gay Movement |Mattachine]] was again taken up in civil rights activism and community building efforts. But it took several years for these elements to converge and for a grassroots gay community to adopt a civil rights agenda and burst into the forum of national politics. | ||

| Line 9: | Line 17: | ||

This development was foreshadowed in 1960 by two events: | This development was foreshadowed in 1960 by two events: | ||

First an internal debate which clarified issues in the movement and drew a line between accommodationism and the emerging activism of the 1960s. Early that year, ONE proposed as the subject of its annual conference the drafting of a | First an internal debate which clarified issues in the movement and drew a line between accommodationism and the emerging activism of the 1960s. Early that year, ONE proposed as the subject of its annual conference the drafting of a "Homosexual Bill of Rights." The proposal drew immediate criticism from the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis. These groups felt that such a document, even for discussion purposes, took "a demanding attitude towards society." | ||

Such a stance would backfire, provoking even greater hostility from the public. | Such a stance would backfire, provoking even greater hostility from the public. | ||

The debate was bitter and relations between Daughters of Bilitis and the men's groups were strained in the following years. Nevertheless, ONE had taken a major step towards a more assertive stand on behalf of gay people. The | The debate was bitter and relations between Daughters of Bilitis and the men's groups were strained in the following years. Nevertheless, ONE had taken a major step towards a more assertive stand on behalf of gay people. The "Homosexual Bill of Rights" was a prototype for the gay civil rights agenda of the 1970s. | ||

The second key event of 1959 occurred in San Francisco where an incumbent mayor [[Mayor George Christopher|Christopher]] was running for reelection. In a desperate move to gain support, the opposing candidate accused the mayor of harboring sexual deviates within the city. He pointed specifically to the Mattachine Society, with its | The second key event of 1959 occurred in San Francisco where an incumbent mayor [[Mayor George Christopher|Christopher]] was running for reelection. In a desperate move to gain support, the opposing candidate accused the mayor of harboring sexual deviates within the city. He pointed specifically to the Mattachine Society, with its "national headquarters" located in San Francisco. This smear tactic failed, however, and the mayor was re-elected in a landslide. But in the course of the debate, the homophobia of both candidates alienated a sizable"presumably gay"group of voters. When the ballots were counted it was found that some nine thousand people had voted for neither candidate. For astute political observers, the 1959 election in San Francisco revealed the political stirrings of an emerging community. | ||

Throughout the early sixties, San Francisco remained a center of gay activism. Police extortion of gay bars became a scandal in 1961 when several bars refused to pay and went to court instead. In the aftermath, gay bar owners formed the Tavern Guild (1962) and worked cooperatively to fight police harassment. In 1964, several liberal ministers became concerned with homosexual rights and formed the Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH). Later that year, CRH sponsored a New Year's ball for the gay community. When the police showed up in force and arrested several of the ministers, the outcry that followed placed an effective restraint on police harassment. | Throughout the early sixties, San Francisco remained a center of gay activism. Police extortion of gay bars became a scandal in 1961 when several bars refused to pay and went to court instead. In the aftermath, gay bar owners formed the Tavern Guild (1962) and worked cooperatively to fight police harassment. In 1964, several liberal ministers became concerned with homosexual rights and formed the Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH). Later that year, CRH sponsored a New Year's ball for the gay community. When the police showed up in force and arrested several of the ministers, the outcry that followed placed an effective restraint on police harassment. | ||

In 1964, a new gay organization was formed in San Francisco, concerned with the development of the gay community, as well as political action. The | In 1964, a new gay organization was formed in San Francisco, concerned with the development of the gay community, as well as political action. The [[Society for Individual Rights (SIR)|Society for Individual Rights]] (SIR) opened a community center in 1966, sponsoring a wide range of social and cultural activities. SIR also held "Candidate's Nights," in which local political candidates fielded questions from a gay audience. In New York, similar developments occurred. In 1968, the gay community won important concessions from the Lindsay administration, reducing police pressure on gay bars. These early victories laid the groundwork for the mass coming out of gay people in the early 1970s, neutralizing the greatest, single obstacle to the gay community — police harassment. | ||

[[ | [[1966 Vanguard Sweep | Prev. Document]] [[Folsom Street: The Miracle Mile | Next Document]] | ||

[[category: | [[category:LGBTQI]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:Polk Gulch]] [[category:Civic Center]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:56, 15 October 2018

Historical Essay

by Will Roscoe

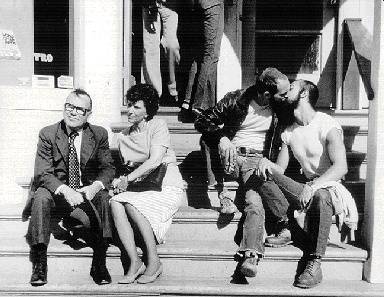

Two Castro Couples -- Love, sweet love.

Photo: Crawford Barton, Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California

| An intersectional gay rights movement came to light in the 1960s when the gay community joined with the momentum of the civil rights movement, anti-war protestors, and feminists. This communal gay rights movement was prefaced by two events. Firstly, a much-debated “Homosexual Bill of Rights” was drafted and acted as a prototype for the gay civil rights agenda of the 1970s. Secondly, the incumbent mayor Christopher was re-elected in 1959 by a landslide even after the opposing candidate ran a smear campaign criticizing the mayor of harboring “sexual deviates” in the city. There were many new political efforts by the early gay community, including the Tavern Guild, the Society for Individual Rights, and the Council on Religion and Homosexuality, that together helped curb rampant anti-gay police brutality. |

In the 1960s, the gay movement absorbed the profound and successive influences of the civil rights, anti-war, feminist and counterculture movements. The broad vision of the early Mattachine was again taken up in civil rights activism and community building efforts. But it took several years for these elements to converge and for a grassroots gay community to adopt a civil rights agenda and burst into the forum of national politics.

This development was foreshadowed in 1960 by two events:

First an internal debate which clarified issues in the movement and drew a line between accommodationism and the emerging activism of the 1960s. Early that year, ONE proposed as the subject of its annual conference the drafting of a "Homosexual Bill of Rights." The proposal drew immediate criticism from the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis. These groups felt that such a document, even for discussion purposes, took "a demanding attitude towards society."

Such a stance would backfire, provoking even greater hostility from the public.

The debate was bitter and relations between Daughters of Bilitis and the men's groups were strained in the following years. Nevertheless, ONE had taken a major step towards a more assertive stand on behalf of gay people. The "Homosexual Bill of Rights" was a prototype for the gay civil rights agenda of the 1970s.

The second key event of 1959 occurred in San Francisco where an incumbent mayor Christopher was running for reelection. In a desperate move to gain support, the opposing candidate accused the mayor of harboring sexual deviates within the city. He pointed specifically to the Mattachine Society, with its "national headquarters" located in San Francisco. This smear tactic failed, however, and the mayor was re-elected in a landslide. But in the course of the debate, the homophobia of both candidates alienated a sizable"presumably gay"group of voters. When the ballots were counted it was found that some nine thousand people had voted for neither candidate. For astute political observers, the 1959 election in San Francisco revealed the political stirrings of an emerging community.

Throughout the early sixties, San Francisco remained a center of gay activism. Police extortion of gay bars became a scandal in 1961 when several bars refused to pay and went to court instead. In the aftermath, gay bar owners formed the Tavern Guild (1962) and worked cooperatively to fight police harassment. In 1964, several liberal ministers became concerned with homosexual rights and formed the Council on Religion and the Homosexual (CRH). Later that year, CRH sponsored a New Year's ball for the gay community. When the police showed up in force and arrested several of the ministers, the outcry that followed placed an effective restraint on police harassment.

In 1964, a new gay organization was formed in San Francisco, concerned with the development of the gay community, as well as political action. The Society for Individual Rights (SIR) opened a community center in 1966, sponsoring a wide range of social and cultural activities. SIR also held "Candidate's Nights," in which local political candidates fielded questions from a gay audience. In New York, similar developments occurred. In 1968, the gay community won important concessions from the Lindsay administration, reducing police pressure on gay bars. These early victories laid the groundwork for the mass coming out of gay people in the early 1970s, neutralizing the greatest, single obstacle to the gay community — police harassment.