COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(added photo) |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

''by Anne B. Bloomfield'' | |||

[[Image:soma1$soma-view-of-palace-hotel-1892.jpg]] | [[Image:soma1$soma-view-of-palace-hotel-1892.jpg]] | ||

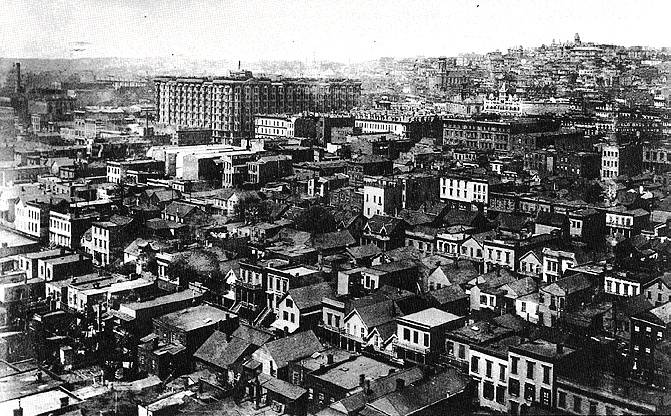

'''Looking northwest in 1892 across South of Market. Large square building is Palace Hotel, and visible slightly above and to its right is the architecturally spectacular Temple Emanu-el on Sutter Street. ''' | '''Looking northwest in 1892 across South of Market. Large square building is Palace Hotel, and visible slightly above and to its right is the architecturally spectacular Temple Emanu-el on Sutter Street. ''' | ||

In 1869 two major changes in the streets south of Market greatly changed the nature of the district. First was the [[2nd St. Cut |Second Street Cut]], which nearly leveled Rincon Hill's one-hundred-foot elevation of sand. The stated goal was to facilitate heavy goods traffic to and from the Pacific Mail Steamship Company's docks and warehouses on the waterfront between First and Second streets (sole survivor of the complex is the 1867 [[Baker and Hamilton |Oriental Warehouse]] near First and Brannan). The hidden agenda was real estate speculation. In spite of granite facing, stairs, and a bridge at the Harrison Street crest, the cut proved brutal surgery on the hill. The sand kept slipping and caving, endangering workmen and wrecking noble houses. Then the wealthy fled from Rincon Hill, leaving the whole South-of-Market area to working-class residents.26 | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | ||

[[Image:View-southeast-from-Nob-Hill-towards-Palace-Hotel-and-Selby-Shot-Tower.jpg]] | |||

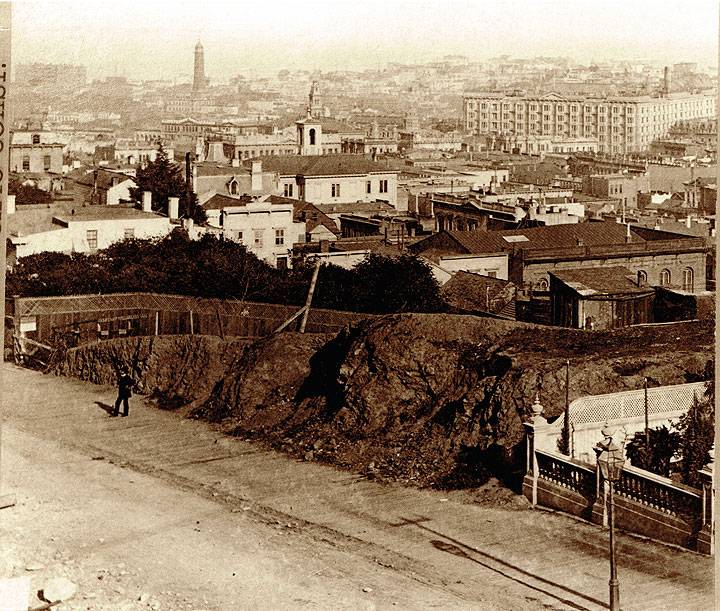

'''Southeast view from Nob Hill towards Palace Hotel (Selby Shot Tower at left).''' | |||

''Photo: courtesy private collector'' | |||

In 1869 two major changes in the streets south of Market greatly changed the nature of the district. First was the [[2nd St. Cut |Second Street Cut]], which nearly leveled Rincon Hill's one-hundred-foot elevation of sand. The stated goal was to facilitate heavy goods traffic to and from the [[Pacific Mail Docks|Pacific Mail Steamship Company]]'s docks and warehouses on the waterfront between First and Second streets (sole survivor of the complex is the 1867 [[Baker and Hamilton |Oriental Warehouse]] near First and Brannan). The hidden agenda was real estate speculation. In spite of granite facing, stairs, and a bridge at the Harrison Street crest, the cut proved brutal surgery on the hill. The sand kept slipping and caving, endangering workmen and wrecking noble houses. Then the wealthy fled from Rincon Hill, leaving the whole South-of-Market area to working-class residents.(26) | |||

The other change in street pattern was the creation of New Montgomery Street. The block of Mission Street from Second to Third had been subdivided by two inner streets, Annie, next to the new California Historical Society headquarters; and Jane, almost equidistant between Second and Annie. The east side of Jane Street became the west side of New Montgomery, and the Palace Hotel occupies the former Jane Street right-of-way.27 | The other change in street pattern was the creation of New Montgomery Street. The block of Mission Street from Second to Third had been subdivided by two inner streets, Annie, next to the [[CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY|new California Historical Society headquarters]]; and Jane, almost equidistant between Second and Annie. The east side of Jane Street became the west side of New Montgomery, and the Palace Hotel occupies the former Jane Street right-of-way.(27) | ||

The developers' intention for the new street was to break through the barrier of the opposing street grids at Market Street and provide a southern outlet for Montgomery Street, the crowded financial center, which had ended at Market. One of the more responsible real estate speculations, this private project bought up all the properties in the vicinity from Market to Howard, opened the new street, and planned a uniform facade for all its buildings. The developers, adventurer-speculator Asbury Harpending and banker and community leader William Chapman Ralston, projected fashionable retail shops (diverted from Second Street) and a continuation of the Montgomery Street type of businesses. They also wanted the street to continue south from Howard to the water, but other property owners blocked it, and money did not buy legislative approval. The two blocks of New Montgomery could be cut because Ralston and Harpending's New Montgomery Street Real Estate Company owned all the land in question.28 | The developers' intention for the new street was to break through the barrier of the opposing street grids at Market Street and provide a southern outlet for Montgomery Street, the crowded financial center, which had ended at Market. One of the more responsible real estate speculations, this private project bought up all the properties in the vicinity from Market to Howard, opened the new street, and planned a uniform facade for all its buildings. The developers, adventurer-speculator Asbury Harpending and banker and community leader [[William Ralston|William Chapman Ralston]], projected fashionable retail shops (diverted from Second Street) and a continuation of the Montgomery Street type of businesses. They also wanted the street to continue south from Howard to the water, but other property owners blocked it, and money did not buy legislative approval. The two blocks of New Montgomery could be cut because Ralston and Harpending's New Montgomery Street Real Estate Company owned all the land in question.(28) | ||

[[Image:Market street where New Montgomery was cut through 1863 AAB-4859.jpg]] | |||

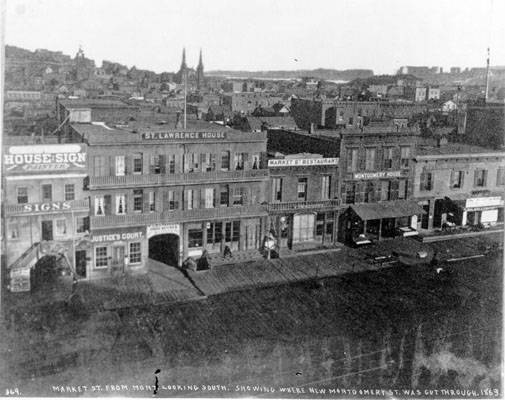

'''Market Street where New Montgomery was cut through after 1863.''' | |||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | |||

Much of this land had been vacant or held old houses. Harpending's memoirs called them "wretched buildings" and "so many backyards," renting at "a very poor return." Except for one parcel, he claimed to have bought eight hundred feet of Market Street frontage, two blocks deep, for less than $500,000. At this time, the Catholic Church sold Harpending and Ralston its large parcel with the Orphan Asylum and St. Patrick's Church.(29) | |||

Important structures soon arose on New Montgomery Street. The Grand Hotel, at the corner of Market Street, dominated the vista from Montgomery Street. Its architect, John P. Gaynor, responded to the earthquake of 1868 by creating brick curtain walls around a heavy timber structural frame, with iron strapping and all parts fastened together. Four stories tall and heavily ornamented, it contained fine shops and four hundred rooms. True to its name, the Grand ranked among San Francisco's top six hotels, along with the Palace, the Baldwin, the Lick, the Occidental, and the Cosmopolitan.(30) | |||

The southern end of New Montgomery Street was lined with three elegant brick buildings containing ground-floor retail stores and, on their mansard-roofed top floors, armory-drill halls for militia units. The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Hall also had a second-floor space called Sanders Hall, for meetings of organizations like Swedish Society, Austrian Benevolent Society, Golden Gate Chapter No. 10 of Eastern Star, Lumbermen's Union, Shipwrights' Association, and Germania Club. The Olympic Club shared one building with the Commercial Yacht Club, rented the middle story to commercial and industrial tenants, and then sold it to the Third Regiment. The Armory Block had only two stories. These three buildings were the only ones designed according to the uniform-facade scheme that Ralston and Harpending had envisioned for all of New Montgomery.(31) | |||

The next important construction project was Ralston's [[Victorian San Francisco|Palace Hotel]], occupying the same site as the Sheraton Palace today and including the previous sites of the Catholic Orphan Asylum and St. Patrick's Church. Ralston wanted the largest and most luxurious hotel in the world, and he spent five million dollars to build and furnish it. Its bay-windowed seven stories dominated the South-of-Market vista. Its open center courtyard, ancestor of the present Garden Court, and its fine public rooms and shops established a lasting attraction for first-class traffic in the neighborhood.(32) | |||

The opera house and luxury hotels created a market for some specialty shops in the first block of Third Street in the 1880s and 1890s. There were tailors, photographers, a glove maker, a jeweler, a silver plate, a costumer, a carpet dealer, and several milliners. Mission Street had a dance hall, another costumer, a sculptor, two mirror and picture dealers, the Grand Floral Market, carriage supply businesses, and two undertakers.36 | The middle section of New Montgomery filled up with auxiliaries to the hotels: livery and boarding stables, a blacksmith shop, carriage repositories, a horse market, gas works for the hotels, and a pedestrian bridge over New Montgomery. The U.S. Army Subsistence, or Quartermaster's, Depot, was on Jessie Street directly behind the Palace. At the corner of Mission Street, the New Metropolitan Market rented stalls to grocers, a dairy, and a sausage maker. Four of San Francisco's ten mineral water suppliers located on New Montgomery, as did two piano dealers.(33) | ||

On Mission Street between Third and Fourth, the new building for St. Patrick's Church was dedicated in March 1872. It was designed by Gordon Parker Cummings, one of the State Capitol architects and responsible for the 1853 Montgomery Block. After the 1906 earthquake and fire, its walls were repaired under the direction of Shea and Lofquist, a new steel frame supported the roof, and the original 240-foot spire was cut down to the square-topped tower that is now the northern focus from Yerba Buena Gardens.(34) | |||

Between St. Patrick's and Third Street, another draw for the carriage trade was the Grand Opera House, seating 2,400 and claiming the largest stage in the nation. Although constructed for opera, the house often played vaudeville and was often dark. Even the elegant opening night on January 17, 1876, featured a combination drama and ballet called "Snowflake," performed by the Fabbri Company. However, the Grand Opera House went out in a blaze of glory, with San Francisco's second visit by New York's Metropolitan Opera Company presenting a wildly cheered performance of "Carmen," starring Enrico Caruso and Olive Fremstad. That was the night of April 17, 1906, and the blaze caused by the next morning's earthquake destroyed the Grand Opera House forever.(35) | |||

The opera house and luxury hotels created a market for some specialty shops in the first block of Third Street in the 1880s and 1890s. There were tailors, photographers, a glove maker, a jeweler, a silver plate, a costumer, a carpet dealer, and several milliners. Mission Street had a dance hall, another costumer, a sculptor, two mirror and picture dealers, the Grand Floral Market, carriage supply businesses, and two undertakers.(36) | |||

In the 1870s, bedding and furniture businesses began to locate on Mission Street around Third and New Montgomery. Rents and spaces must have been suitable for selling bulky objects. The trend lasted through most of the twentieth century. City directories listed four furniture businesses in the neighborhood in 1871, five in 1875, fifteen from 1877 to 1879, sixteen in 1882, eighteen in 1886, thirteen in 1894, and fourteen in 1901. Other establishments offered mattresses and bed springs, lamps, mirrors, gilding, and curled hair for mattresses and upholstery. | In the 1870s, bedding and furniture businesses began to locate on Mission Street around Third and New Montgomery. Rents and spaces must have been suitable for selling bulky objects. The trend lasted through most of the twentieth century. City directories listed four furniture businesses in the neighborhood in 1871, five in 1875, fifteen from 1877 to 1879, sixteen in 1882, eighteen in 1886, thirteen in 1894, and fourteen in 1901. Other establishments offered mattresses and bed springs, lamps, mirrors, gilding, and curled hair for mattresses and upholstery. | ||

The rise and fall of one business may be typical. The Indianapolis Chair Manufacturing Company was founded north of Market about 1876 by Frederick Rentschler, Charles Wollpert, and Jacob Schwerdt. By 1879 they had moved to the second block of New Montgomery Street and were growing. In 1885 the partners split up, Rentschler operating the short-lived Indianapolis Manufacturing Company on Mission east of Annie. Wollpert and Schwerdt became the Indianapolis Furniture Company, in a five-story building just beyond St. Patrick's and employing about sixty-five people. A discount house that specialized in outfitting hotels and rooming houses, they claimed customers all over the West, and in Hawaii, Central America, and Australia. By 1894 Wollpert had incorporated the firm, and Schwerdt operated separately. After the 1906 earthquake and fire, the company continued in the 800 block of Mission Street until World War I.37 | The rise and fall of one business may be typical. The Indianapolis Chair Manufacturing Company was founded north of Market about 1876 by Frederick Rentschler, Charles Wollpert, and Jacob Schwerdt. By 1879 they had moved to the second block of New Montgomery Street and were growing. In 1885 the partners split up, Rentschler operating the short-lived Indianapolis Manufacturing Company on Mission east of Annie. Wollpert and Schwerdt became the Indianapolis Furniture Company, in a five-story building just beyond St. Patrick's and employing about sixty-five people. A discount house that specialized in outfitting hotels and rooming houses, they claimed customers all over the West, and in Hawaii, Central America, and Australia. By 1894 Wollpert had incorporated the firm, and Schwerdt operated separately. After the 1906 earthquake and fire, the company continued in the 800 block of Mission Street until World War I.(37) | ||

''--from "A History of the California Historical Society's New Mission Street Neighborhood" by Anne B. Bloomfield in ''California History'' magazine, Winter 1995/96'' | ''--from "A History of the California Historical Society's New Mission Street Neighborhood" by Anne B. Bloomfield in ''California History'' magazine, Winter 1995/96'' | ||

Latest revision as of 22:59, 27 December 2018

Historical Essay

by Anne B. Bloomfield

Looking northwest in 1892 across South of Market. Large square building is Palace Hotel, and visible slightly above and to its right is the architecturally spectacular Temple Emanu-el on Sutter Street.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Southeast view from Nob Hill towards Palace Hotel (Selby Shot Tower at left).

Photo: courtesy private collector

In 1869 two major changes in the streets south of Market greatly changed the nature of the district. First was the Second Street Cut, which nearly leveled Rincon Hill's one-hundred-foot elevation of sand. The stated goal was to facilitate heavy goods traffic to and from the Pacific Mail Steamship Company's docks and warehouses on the waterfront between First and Second streets (sole survivor of the complex is the 1867 Oriental Warehouse near First and Brannan). The hidden agenda was real estate speculation. In spite of granite facing, stairs, and a bridge at the Harrison Street crest, the cut proved brutal surgery on the hill. The sand kept slipping and caving, endangering workmen and wrecking noble houses. Then the wealthy fled from Rincon Hill, leaving the whole South-of-Market area to working-class residents.(26)

The other change in street pattern was the creation of New Montgomery Street. The block of Mission Street from Second to Third had been subdivided by two inner streets, Annie, next to the new California Historical Society headquarters; and Jane, almost equidistant between Second and Annie. The east side of Jane Street became the west side of New Montgomery, and the Palace Hotel occupies the former Jane Street right-of-way.(27)

The developers' intention for the new street was to break through the barrier of the opposing street grids at Market Street and provide a southern outlet for Montgomery Street, the crowded financial center, which had ended at Market. One of the more responsible real estate speculations, this private project bought up all the properties in the vicinity from Market to Howard, opened the new street, and planned a uniform facade for all its buildings. The developers, adventurer-speculator Asbury Harpending and banker and community leader William Chapman Ralston, projected fashionable retail shops (diverted from Second Street) and a continuation of the Montgomery Street type of businesses. They also wanted the street to continue south from Howard to the water, but other property owners blocked it, and money did not buy legislative approval. The two blocks of New Montgomery could be cut because Ralston and Harpending's New Montgomery Street Real Estate Company owned all the land in question.(28)

Market Street where New Montgomery was cut through after 1863.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Much of this land had been vacant or held old houses. Harpending's memoirs called them "wretched buildings" and "so many backyards," renting at "a very poor return." Except for one parcel, he claimed to have bought eight hundred feet of Market Street frontage, two blocks deep, for less than $500,000. At this time, the Catholic Church sold Harpending and Ralston its large parcel with the Orphan Asylum and St. Patrick's Church.(29)

Important structures soon arose on New Montgomery Street. The Grand Hotel, at the corner of Market Street, dominated the vista from Montgomery Street. Its architect, John P. Gaynor, responded to the earthquake of 1868 by creating brick curtain walls around a heavy timber structural frame, with iron strapping and all parts fastened together. Four stories tall and heavily ornamented, it contained fine shops and four hundred rooms. True to its name, the Grand ranked among San Francisco's top six hotels, along with the Palace, the Baldwin, the Lick, the Occidental, and the Cosmopolitan.(30)

The southern end of New Montgomery Street was lined with three elegant brick buildings containing ground-floor retail stores and, on their mansard-roofed top floors, armory-drill halls for militia units. The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Hall also had a second-floor space called Sanders Hall, for meetings of organizations like Swedish Society, Austrian Benevolent Society, Golden Gate Chapter No. 10 of Eastern Star, Lumbermen's Union, Shipwrights' Association, and Germania Club. The Olympic Club shared one building with the Commercial Yacht Club, rented the middle story to commercial and industrial tenants, and then sold it to the Third Regiment. The Armory Block had only two stories. These three buildings were the only ones designed according to the uniform-facade scheme that Ralston and Harpending had envisioned for all of New Montgomery.(31)

The next important construction project was Ralston's Palace Hotel, occupying the same site as the Sheraton Palace today and including the previous sites of the Catholic Orphan Asylum and St. Patrick's Church. Ralston wanted the largest and most luxurious hotel in the world, and he spent five million dollars to build and furnish it. Its bay-windowed seven stories dominated the South-of-Market vista. Its open center courtyard, ancestor of the present Garden Court, and its fine public rooms and shops established a lasting attraction for first-class traffic in the neighborhood.(32)

The middle section of New Montgomery filled up with auxiliaries to the hotels: livery and boarding stables, a blacksmith shop, carriage repositories, a horse market, gas works for the hotels, and a pedestrian bridge over New Montgomery. The U.S. Army Subsistence, or Quartermaster's, Depot, was on Jessie Street directly behind the Palace. At the corner of Mission Street, the New Metropolitan Market rented stalls to grocers, a dairy, and a sausage maker. Four of San Francisco's ten mineral water suppliers located on New Montgomery, as did two piano dealers.(33)

On Mission Street between Third and Fourth, the new building for St. Patrick's Church was dedicated in March 1872. It was designed by Gordon Parker Cummings, one of the State Capitol architects and responsible for the 1853 Montgomery Block. After the 1906 earthquake and fire, its walls were repaired under the direction of Shea and Lofquist, a new steel frame supported the roof, and the original 240-foot spire was cut down to the square-topped tower that is now the northern focus from Yerba Buena Gardens.(34)

Between St. Patrick's and Third Street, another draw for the carriage trade was the Grand Opera House, seating 2,400 and claiming the largest stage in the nation. Although constructed for opera, the house often played vaudeville and was often dark. Even the elegant opening night on January 17, 1876, featured a combination drama and ballet called "Snowflake," performed by the Fabbri Company. However, the Grand Opera House went out in a blaze of glory, with San Francisco's second visit by New York's Metropolitan Opera Company presenting a wildly cheered performance of "Carmen," starring Enrico Caruso and Olive Fremstad. That was the night of April 17, 1906, and the blaze caused by the next morning's earthquake destroyed the Grand Opera House forever.(35)

The opera house and luxury hotels created a market for some specialty shops in the first block of Third Street in the 1880s and 1890s. There were tailors, photographers, a glove maker, a jeweler, a silver plate, a costumer, a carpet dealer, and several milliners. Mission Street had a dance hall, another costumer, a sculptor, two mirror and picture dealers, the Grand Floral Market, carriage supply businesses, and two undertakers.(36)

In the 1870s, bedding and furniture businesses began to locate on Mission Street around Third and New Montgomery. Rents and spaces must have been suitable for selling bulky objects. The trend lasted through most of the twentieth century. City directories listed four furniture businesses in the neighborhood in 1871, five in 1875, fifteen from 1877 to 1879, sixteen in 1882, eighteen in 1886, thirteen in 1894, and fourteen in 1901. Other establishments offered mattresses and bed springs, lamps, mirrors, gilding, and curled hair for mattresses and upholstery.

The rise and fall of one business may be typical. The Indianapolis Chair Manufacturing Company was founded north of Market about 1876 by Frederick Rentschler, Charles Wollpert, and Jacob Schwerdt. By 1879 they had moved to the second block of New Montgomery Street and were growing. In 1885 the partners split up, Rentschler operating the short-lived Indianapolis Manufacturing Company on Mission east of Annie. Wollpert and Schwerdt became the Indianapolis Furniture Company, in a five-story building just beyond St. Patrick's and employing about sixty-five people. A discount house that specialized in outfitting hotels and rooming houses, they claimed customers all over the West, and in Hawaii, Central America, and Australia. By 1894 Wollpert had incorporated the firm, and Schwerdt operated separately. After the 1906 earthquake and fire, the company continued in the 800 block of Mission Street until World War I.(37)

--from "A History of the California Historical Society's New Mission Street Neighborhood" by Anne B. Bloomfield in California History magazine, Winter 1995/96