Loma Prieta Earthquake, 1989: Difference between revisions

m (Protected "Loma Prieta Earthquake, 1989" ([edit=sysop] (indefinite) [move=sysop] (indefinite))) |

(added photo, fixed formatting) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

''Photo: Oct. 17, 1989, by H.G. Wilshire, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey'' | ''Photo: Oct. 17, 1989, by H.G. Wilshire, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey'' | ||

[[Image:Marina-District-after-89-quake-from-air Chris-Hardy SFImage.jpg]] | |||

'''Aerial view of devastation in Marina District.''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Hardy, SF Image'' | |||

In the weeks and months after the quake, the overwhelming sentiment in San Francisco was “it could have been worse.” Although a strong earthquake, it was centered about 60 miles south of San Francisco in Santa Cruz County, meaning that the bulk of the destructive force was centered on the sparsely populated and mostly agricultural communities of Santa Cruz, Watsonville and Salinas. While these areas endured more devastation on a per-capita basis, San Francisco and Oakland coped with significantly more damage overall. The fabled [[April 18, 1906: EARTHQUAKE! FIRE!|1906 earthquake]] registered magnitude 7.8 and caused four times more property damage to a San Francisco half as big as it would be in 1989. | In the weeks and months after the quake, the overwhelming sentiment in San Francisco was “it could have been worse.” Although a strong earthquake, it was centered about 60 miles south of San Francisco in Santa Cruz County, meaning that the bulk of the destructive force was centered on the sparsely populated and mostly agricultural communities of Santa Cruz, Watsonville and Salinas. While these areas endured more devastation on a per-capita basis, San Francisco and Oakland coped with significantly more damage overall. The fabled [[April 18, 1906: EARTHQUAKE! FIRE!|1906 earthquake]] registered magnitude 7.8 and caused four times more property damage to a San Francisco half as big as it would be in 1989. | ||

| Line 35: | Line 41: | ||

''Photo: Oct. 17, 1989 by J.K. Nakata, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey'' | ''Photo: Oct. 17, 1989 by J.K. Nakata, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey'' | ||

[[Image:Collapsed Bay Bridge 016sr.jpg|left|300px | [[Image:Collapsed Bay Bridge 016sr.jpg|left|300px]] '''Aerial view of collapsed Bay Bridge looking westward''' | ||

''Photo: C.E. Meyer, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey'' | |||

The most enduring image of the Loma Prieta quake is that of a section of the Bay Bridge’s upper deck collapsed onto the eastbound lower deck. One person died when her car plunged into the 50-foot gap left by the missing section. In Oakland, 42 people were killed in one three-quarters of a mile stretch of a similar double-decker freeway that fell down in the quake. Called the Cypress Street Viaduct, it was the single most deadly place in the aftermath of the earthquake. It was not rebuilt. The California Highway Patrol’s report on the transportation deaths argued that baseball saved countless lives: “the afternoon commute traffic was lighter than usual for the Bay Area. This was directly attributable to the third game of the World Series … a large number of people were already at the stadium and an equally large number of people left work early to participate in pre-game activities” (''1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake Summary Report''). | |||

The Loma Prieta earthquake was the first natural disaster to be broadcast live to the nation. Coincidentally striking the city mere minutes before the first pitch of Game 3 of the World Series in [[Candlestick Swindle|Candlestick Park]], ABC’s cameras were rolling and their sportscasters reported the first news of the quake to the worried nation. Still today, the first clip and subsequent journalism that earned sports reporter Al Michaels an Emmy nomination for his hard news coverage can be viewed on Youtube. The Goodyear blimp, originally above the baseball stadium, ventured over the city to transfer images of the damage across the world. “We got almost to the Embarcadero, so close that I could see the collapsed section of the bridge with our high-powered lens,” recalled Jim Crayton, blimp pilot for 37 years. “It was eerie: All of downtown San Francisco was pitch-black except for the glow of the fires.” (Brinklow, et al.) | The Loma Prieta earthquake was the first natural disaster to be broadcast live to the nation. Coincidentally striking the city mere minutes before the first pitch of Game 3 of the World Series in [[Candlestick Swindle|Candlestick Park]], ABC’s cameras were rolling and their sportscasters reported the first news of the quake to the worried nation. Still today, the first clip and subsequent journalism that earned sports reporter Al Michaels an Emmy nomination for his hard news coverage can be viewed on Youtube. The Goodyear blimp, originally above the baseball stadium, ventured over the city to transfer images of the damage across the world. “We got almost to the Embarcadero, so close that I could see the collapsed section of the bridge with our high-powered lens,” recalled Jim Crayton, blimp pilot for 37 years. “It was eerie: All of downtown San Francisco was pitch-black except for the glow of the fires.” (Brinklow, et al.) | ||

Latest revision as of 09:00, 7 October 2019

Historical Essay

by Sloane Sturzenegger, 2015

- San Andreas

- every

- body’s

- fault

- —Francisco X. Alarcón

- San Andreas

On October 17, 1989 at 5:04 in the evening a 7.1 magnitude earthquake struck the San FranciscoBay Area.

The ground shook for only fifteen seconds, but that brief quarter-minute started fires, destroyed highways, united San Francisco, caused the deaths of 62, delayed a World Series, broke the Bay Bridge, and inspired a university professor to write a book of poems called Loma Prieta – the name of the mountain at the epicenter of the quake and subsequently assigned to the disaster.

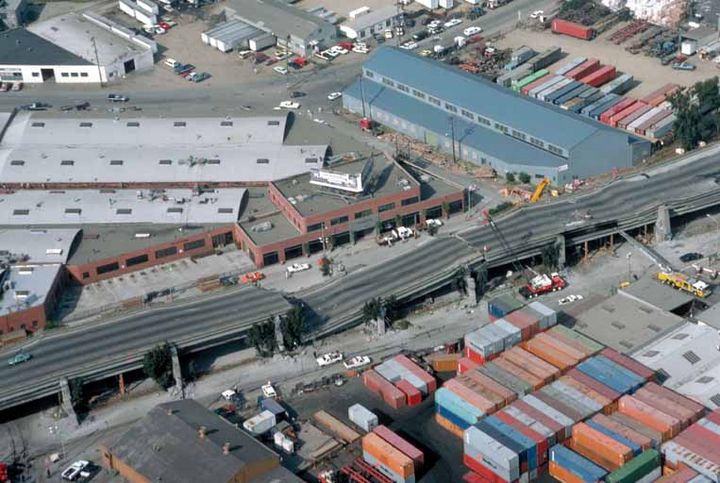

Cypress structure, part of Interstate-880 (the Nimitz Freeway) in West Oakland shortly after being wrecked by the Loma Prieta earthquake on Oct. 17, 1989.

Photo: Oct. 17, 1989, by H.G. Wilshire, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey

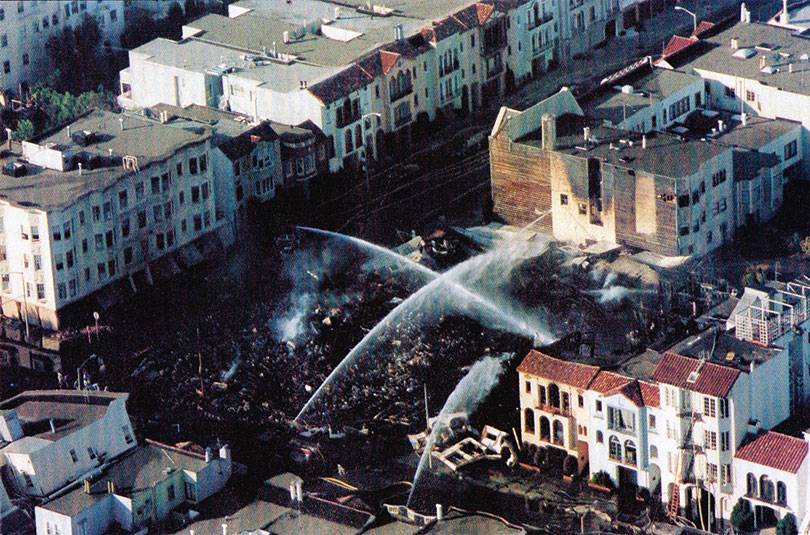

Aerial view of devastation in Marina District.

Photo: Chris Hardy, SF Image

In the weeks and months after the quake, the overwhelming sentiment in San Francisco was “it could have been worse.” Although a strong earthquake, it was centered about 60 miles south of San Francisco in Santa Cruz County, meaning that the bulk of the destructive force was centered on the sparsely populated and mostly agricultural communities of Santa Cruz, Watsonville and Salinas. While these areas endured more devastation on a per-capita basis, San Francisco and Oakland coped with significantly more damage overall. The fabled 1906 earthquake registered magnitude 7.8 and caused four times more property damage to a San Francisco half as big as it would be in 1989.

In San Francisco proper, the statistics present a blunt description of the damage: 12 deaths. 300 injuries. Two billion dollars worth of destroyed property. (1989 Northern California Earthquake) The Marina district was the hardest hit — instead of standing on solid earth the whole neighborhood is constructed on sandy landfill and rubble dragged into the Bay during reconstruction after the 1906 earthquake. The fire department’s water mains were destroyed by the shockwaves in the suddenly liquefied ground, and only the quick decision to use fireboats in the Bay to fight fire on the land prevented the flames from engulfing more of the city. The top floors of many Victorian homes in the Marina district collapsed into the open, unsupported garage space on the ground floor. Only in 2013 did San Francisco introduce a mandatory retrofit program for these so-called “soft story” buildings (Mandatory Soft Story Program).

Absence of adequate shear walls on the garage level exacerbated damage to this structure at the corner of Beach and Divisadero Streets, Marina District.

Photo: Oct 17 1989, by J.K. Nakata, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey

An automobile lies crushed under the third story of this apartment building in the Marina District. The ground levels are no longer visible because of structural failure and sinking due to liquefaction.

Photo: Oct. 17, 1989 by J.K. Nakata, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey

Aerial view of collapsed Bay Bridge looking westward

Photo: C.E. Meyer, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey

The most enduring image of the Loma Prieta quake is that of a section of the Bay Bridge’s upper deck collapsed onto the eastbound lower deck. One person died when her car plunged into the 50-foot gap left by the missing section. In Oakland, 42 people were killed in one three-quarters of a mile stretch of a similar double-decker freeway that fell down in the quake. Called the Cypress Street Viaduct, it was the single most deadly place in the aftermath of the earthquake. It was not rebuilt. The California Highway Patrol’s report on the transportation deaths argued that baseball saved countless lives: “the afternoon commute traffic was lighter than usual for the Bay Area. This was directly attributable to the third game of the World Series … a large number of people were already at the stadium and an equally large number of people left work early to participate in pre-game activities” (1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake Summary Report).

The Loma Prieta earthquake was the first natural disaster to be broadcast live to the nation. Coincidentally striking the city mere minutes before the first pitch of Game 3 of the World Series in Candlestick Park, ABC’s cameras were rolling and their sportscasters reported the first news of the quake to the worried nation. Still today, the first clip and subsequent journalism that earned sports reporter Al Michaels an Emmy nomination for his hard news coverage can be viewed on Youtube. The Goodyear blimp, originally above the baseball stadium, ventured over the city to transfer images of the damage across the world. “We got almost to the Embarcadero, so close that I could see the collapsed section of the bridge with our high-powered lens,” recalled Jim Crayton, blimp pilot for 37 years. “It was eerie: All of downtown San Francisco was pitch-black except for the glow of the fires.” (Brinklow, et al.)

Collapsed Cypress Structure on Nimitz Freeway in West Oakland, Oct. 17, 1989.

Photo: H.G. Wilshire, courtesy U.S. Geological Survey

In the immediate aftermath, both San Franciscans in uniform and in Levi’s worked together to take care of their community. According to the California legislature’s disaster report, “The cities and communities of San Francisco, Oakland, Santa Cruz, Watsonville, and others threw their emergency agencies into the fight against further damage and loss of life. The cooperation between state, local, and federal officials was exemplary” (Roberti 1). Red Cross volunteers flocked to the emergency shelters that were hastily erected at Marina Middle School, the army barracks in the Presidio, a publishing house in the Tenderloin and aboard the USS Peleliu in the Bay (1989 Northern California Earthquake Appendix 6). Mayor Art Agnos has nothing but praise for the calm and composed attitude that San Franciscans exhibited in the wake of the disaster. “There was no rioting, no looting, no abuse of other people. One neighbor helping another. People were looking for others to help. As diverse a city as we are, we showed we were made of the all-American right stuff in one of the worst crises of the last 90 years.” (Brinklow, et. al)

Politicians swung into action shortly after the quake. In a roundly criticized media stunt, Vice President Dan Quayle visited the Marina district on the day after the quake but left San Francisco without meeting with Mayor Agnos (who had still not slept since the quake struck). President George H. W. Bush visited San Francisco and Oakland on the twentieth and by October 24 the federal government allocated $2.85 billion to the relief effort. This was followed by an “Extraordinary Session” of the already recessed California legislature which in only three days resulted in the Senate and Assembly passing 24 bills through twelve committees allocating emergency funds totaling more than a billion dollars to the Bay Area.(Roberti 3) In addition, more than 35 additional bills were written by various state senators in that session but only considered when the legislature reconvened in January. These bills ranged as far and wide as establishing a California emergency satellite communications grid and reimbursing alcohol distributors for spilled booze contained in the bottles that broke in the quake. Even with relief money flowing directly to individuals and into departments that would reconstruct public infrastructure and buildings, the earthquake still left $2 to $5 billion of the overall damage to be absorbed by Bay Area residents and businesses. (Benuska 413)

The Loma Prieta disaster speaks volumes to the character of the City. During and after the quake, the city unified as it repaired its infrastructure, rebuilt homes, and returned to normalcy. The federal, state and city governments worked together to provide much-needed relief to the citizens and businesses of San Francisco. Only ten days after the tremor, the World Series resumed and announcer Al Michaels described how sudden the earthquake had come to this lively city: “the feeling of pure radiance was transformed into horror and grief and despair — in just fifteen seconds. And now on October 27, like a fighter who's taken a vicious blow to the stomach and has groggily arisen, this region moves on and moves ahead. … And while the mourning and the suffering and the aftereffects will continue, in about thirty minutes the plate umpire, Vic Voltaggio will say ‘Play Ball', and the players will play, the vendors will sell, the announcers will announce, the crowd will exhort. And for many of the six million people in this region, it will be like revisiting Fantasyland” (Marquez 1 and 2). The city’s recovery took much longer than ten days, but the prompt restart of the World Series was symbolic of the entire City. San Francisco would rebuild and recover and renew, just as it always has and just as it always will.

Works Cited

1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake Summary Report. Sacramento. State of California Department of California Highway Patrol. 1990.

1989 Northern California Earthquake: Legislative Response. Sacramento, CA: Joint Publications, 1989.

1989 Northern California Earthquake. Sacramento. California State Legislature. Senate First Extraordinary Committee. 1989.

Benuska, Lee, and James E. Beavers, eds. "Loma Prieta Earthquake Reconnaissance Report." Earthquake Spectra Supplement to 6 (1990): n. pag. Print.

Effects of the October 17, 1989 Earthquake On Employment. [Sacramento]: Employment Development Dept., Labor Market Information Division, 1990.

Hager, Philip. "Claim Settled in the Only Quake Death, Injury on Bay Bridge." Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, 01 May 1991. Web. 22 May 2015.

Lubinsky, Annie. "Goodyear Blimp Pilot Will Recall Watching Decades of Historic Events from the Sky." Daily Breeze. Media NewsGroup, Inc., 17 Jan. 2017. Web. 22 May 2015.

“Mandatory Soft Story Program.” Department of Building Inspection. City and County of San Francisco, 2013. Web. 22 May 2015.

Marquez, Donald. "Series, Interrupted." Athletics Nation. Oakland Athletics, 17 Oct. 2009. Web. 22 May 2015.

Marquez, Donald. "Weird Thing, Sports." Athletics Nation. Oakland Athletics, 12 Oct. 2011. Web. 22 May 2015.

Roberti, David. The Northern California Earthquake. Sacramento, CA: Joint Publications, 1990.

“San Francisco Earthquake History 1915-1989.” Virtual Museum of San Francisco. The Museum of the City of San Francisco, n.d. Web. 22 May 2015.

“Tales From the Brink: An Oral History of the Loma Prieta Earthquake.” San Francisco Magazine. Ed. Adam L. Brinklow, Andrea Powell, and Kate Van Brocklin. Modern Luxury, 17 Oct. 2014. Web. 22 May 2015.

The Impact of Natural Disasters On California's Tourism Industry : Interim Hearing. Sacramento, CA: Senate Publications, 1990.