New Wave Against Black Lung: Miners' Benefit 1978: Difference between revisions

(Created page with " ''by Keith Bollinger; this essay and its quotes are from the liner notes to the album "Miners' Benefit" published in 2003 by White Noise Records, used here with permission....") |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

''by Keith Bollinger, 2003; this essay and its quotes are from the liner notes to the album "Miners' Benefit" published in 2003 by White Noise Records, used here with permission.'' | |||

''by Keith Bollinger; this essay and its quotes are from the liner notes to the album "Miners' Benefit" published in 2003 by White Noise Records, used here with permission.'' | |||

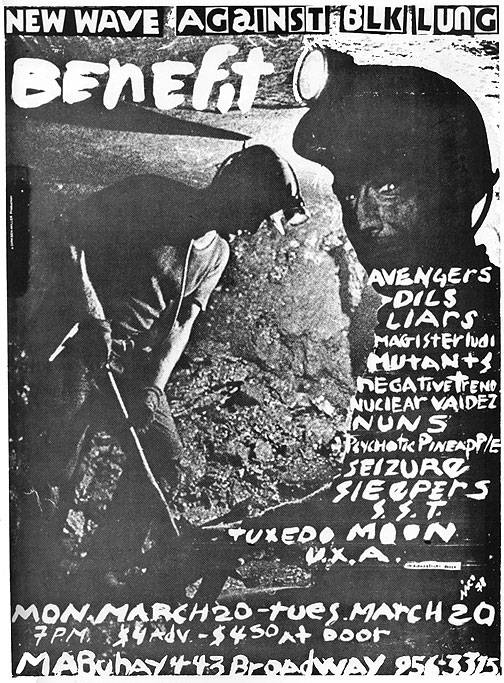

[[Image:New-wave-against-black-lung-benefit-at-fab-mab-march-1978.jpg]] | [[Image:New-wave-against-black-lung-benefit-at-fab-mab-march-1978.jpg]] | ||

In 1977 a group of bands converged at the [[Negative Trend Erupts at Mabuhay Gardens|Mabuhay Gardens]], a Filipino supper club and piano bar located in San Francisco’s North Beach. Mabuhay impresario Dirk Dirksen | In 1977 a group of bands converged at the [[Negative Trend Erupts at Mabuhay Gardens|Mabuhay Gardens]], a Filipino supper club and piano bar located in San Francisco’s North Beach. Mabuhay impresario Dirk Dirksen started modestly by presenting a comedy group and other non-rock’n’roll acts, but held a unique vision at the outset. ''“The reason we started the Mab was, I was working on a concept of documenting the creative process for, at that point, a series of television shows. And so it was like what Toulouse-Lautrec did with the sketch pad, at the Moulin Rouge; because he had the best lithographers working for him, because he had that opportunity to document. And his idea was to document not just the performance, but all the hangers-on and what creates the scene in which the seminal moment of a perform occurs. And that’s been my sort of, over the years, my … focus, or study of the creative process. So I needed a venue in which to establish the peripheries in which artists and their friends could hang out, while we would document it. And so I came to San Francisco with the purpose of finding a venue in which I could do that.”'' | ||

The Nuns, Crime, Mary Monday and the Dils were the earliest and most prominent in attracting a new kind of audience to the Mabuhay. Speaking about his bandmates but applying in a broader sense to the scene itself, Mutants' drummer Dave Carothers recalls, "It kind of drew you closer together, you know, [we're] like this little group trying to make a dent in the San Francisco music system." Stylistically diverse, these early bands were united in their need for an alternative to the existing club scene that was not hospitable to bands who had an affinity, sonic or otherwise, with the British punk explosion. | The Nuns, Crime, Mary Monday and the Dils were the earliest and most prominent in attracting a new kind of audience to the Mabuhay. Speaking about his bandmates but applying in a broader sense to the scene itself, Mutants' drummer Dave Carothers recalls, "It kind of drew you closer together, you know, [we're] like this little group trying to make a dent in the San Francisco music system." Stylistically diverse, these early bands were united in their need for an alternative to the existing club scene that was not hospitable to bands who had an affinity, sonic or otherwise, with the British punk explosion. | ||

Latest revision as of 20:05, 9 November 2019

Historical Essay

by Keith Bollinger, 2003; this essay and its quotes are from the liner notes to the album "Miners' Benefit" published in 2003 by White Noise Records, used here with permission.

In 1977 a group of bands converged at the Mabuhay Gardens, a Filipino supper club and piano bar located in San Francisco’s North Beach. Mabuhay impresario Dirk Dirksen started modestly by presenting a comedy group and other non-rock’n’roll acts, but held a unique vision at the outset. “The reason we started the Mab was, I was working on a concept of documenting the creative process for, at that point, a series of television shows. And so it was like what Toulouse-Lautrec did with the sketch pad, at the Moulin Rouge; because he had the best lithographers working for him, because he had that opportunity to document. And his idea was to document not just the performance, but all the hangers-on and what creates the scene in which the seminal moment of a perform occurs. And that’s been my sort of, over the years, my … focus, or study of the creative process. So I needed a venue in which to establish the peripheries in which artists and their friends could hang out, while we would document it. And so I came to San Francisco with the purpose of finding a venue in which I could do that.”

The Nuns, Crime, Mary Monday and the Dils were the earliest and most prominent in attracting a new kind of audience to the Mabuhay. Speaking about his bandmates but applying in a broader sense to the scene itself, Mutants' drummer Dave Carothers recalls, "It kind of drew you closer together, you know, [we're] like this little group trying to make a dent in the San Francisco music system." Stylistically diverse, these early bands were united in their need for an alternative to the existing club scene that was not hospitable to bands who had an affinity, sonic or otherwise, with the British punk explosion.

"Back in the early days, I think there was more of a political atmosphere. People had a feeling that they were out to change something. They were making a statement. People knew each other and they'd go out for a reason. There were a lot of things happening but the music was pretty much a focal point." —John Gullak (Mutants).

Launched within an era of crisis, Rock Against Racism ("RAR") captured the imagination of British music fans and quickly gained the support of the Clash, Tom Robinson Band, X-Ray Spex, Johnny Rotten, Generation X and others. RAR expressed a new cultural revolt reacting to many forms of oppression and sparked a genuine youth movement. One of RAR’s memorable slogans: “Knock Hard. Life is Deaf.” San Francisco disc jockey and writer Howie Klein traveled to Europe during February 1978—focusing on the British music scene in particular—and returned greatly inspired by the social consciousness embodied by the Clash and RAR.

By fall 1977 labor negotiations between the U.S. coal industry and its workers became deadlocked; the right-to-strike over unsafe working conditions became a hotly contested topic among several being discussed. Particularly compelling was the story of a group of miners in Stearns, Kentucky, who had been on strike since July 1976 in their quest for union recognition. The Washington Post would describe the strike in Stearns as “thoroughly dramatic as anything from labor’s great organizing days: armed camps, company cops, shootings, woundings, jailings, beatings, suffering families and resolute men and women.” During December 1977 the United Mine Workers went on strike, and it’s no understatement to say this caused a national energy crisis which would later be described by a coal industry official as “… an industrial Armageddon.”

Within two weeks of returning from London, Howie Klein and members of the Dils, Negative Trend, the Nuns and Magister Ludi organized a huge two-night benefit for striking coal miners. At an organizational meeting held on March 10th, plans for the benefit were finalized and ninety percent of the gate money was earmarked for the strikers in Stearns, Kentucky. Nuns' guitarist Alejandro Escovedo told journalist Lynn X, “The idea for the benefit seemed like a good opportunity to get everyone thinking, to raise the consciousness a little more.” Escovedo added, “It's not like all of a sudden we're taking a political stance or anything... People always mistake being socially aware for being political.”

Interviewed one week before the Miners' Benefit, Tony Kinman (Dils bassist) expressed his thoughts: “Basically, what the media tried to do to us, to punk rock which is to try to co-opt us, make us seem stupid, and neutralize any real strength our movement had or still has—they're trying to do the same thing to the miners by misrepresenting their cause and their problems to the people.”

When asked if there were other issues the bands wished to rally behind, Kinman responded that he felt it was “futile” to look for “a specific bandwagon to jump on.” “Basically what it is, I think, is just developing a sense of purpose. You know, ‘a reason for living,’ so to speak. That doesn’t mean just reading the paper and [saying] ‘What can I support now?’ But it means caring about these things, and not just, you know, being concerned with the mine workers on the East Coast and in the Lakes area. But also being concerned with a lot of the problems we have right here, in the City—like a lot of problems the gays have here… or the blacks, or even punks getting thrown out of restaurants. Something as petty as that is a symptom of a much larger problem. You know, it’s a symptom of something as basic and wrong as intolerance, bigotry—and just mindless hatred. You don’t have to go around looking for bandwagons to jump on; they’re right there. All’s you’ve got to do is, like open your eyes...”

Kinman concluded by speaking about the media’s slanted portrayal of ‘punk:’ “...It was seized upon by the communications systems in order to co-opt and neutralize punk, which originally—and still has—a very aggressive stand. You know, ‘bent on change.’ Punk catchwords are ‘destroy,’ ‘anarchy,’ ‘chaos,’ and so on. And these things—they aren’t just words. You know, they’ve become cliches now, but they’re not; they mean something. You destroy corporations, you destroy the record industry, you destroy the rock press. You destroy stupid reformist action groups that don’t really remedy a problem, in order to replace it with something different, Because these things aren’t going to go away. And I think that somebody somewhere along the line, [the] people in power, realize that this is exactly what we were talking about. And so they set out to make punk rock look as foolish as possible. That’s an old traditional trick of people in power; to make their opposition—to make somebody truly dangerous—into fools and clowns, if they can.”

Featuring most of the Mabuhay’s popular bands, the Miners’ Benefit (March 20/21, 1978) was held at a time which was arguably the early scene’s peak—before hopes of reaching a greater audience were dashed by a timid record industry who decided to ‘push’ less challenging or controversial bands. The benefit was held months after Sire Records’ successful release of Richard Hell and the Dead Boys albums, and was a moment of uncertain hope for a successful musical revolt by American youth. Just to keep everything in perspective: the Eagles, Fleetwood Mac, and the ‘Saturday Night Fever’ soundtrack ruled the music industry during this era. Also, many of the bands who performed at the Miners’ Benefit had just gotten together; for instance, the Sleepers played their first show less than three months prior. At the Miners’ Benefit a crew filmed and recorded some bands’ performances, from which this release was culled. While from a technical standpoint, these audio recordings are less than ideal—falling mic stands, tuning difficulties, erratic mixing and equipment gremlins are to be heard—they provide a fascinating aural experience of an early Mabuhay show. In the particular case of Negative Trend, all of their set captured on tape is presented for your enjoyment—startups, runouts, tuneupes and tantrums—per Craig Gray’s wishes to provide the listener with a ‘you are there’ experience.

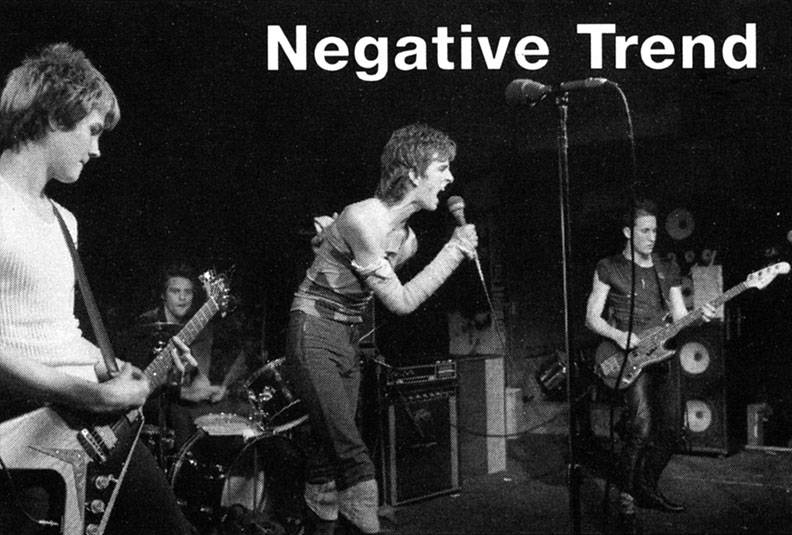

Negative Trend at the 1978 Coal Miners' Benefit at Mabuhay Gardens.

Photo: James Stark

On March 22, the day after the benefit, a cashier’s check for $3,300 was cut and sent to Stearns, Kentucky. Members of the United Mine Workers voted on March 24 to approve a third contract proposal, resolving the strike on a national level (this came after President Jimmy Carter’s unsuccessful invoking of the Taft-Hartley Act on March 6, a law designed to force strikers back to work). John Silvers, drummer for the Dils, recounts that they later heard from the miners in Stearns: “They wrote us back… and said, ‘We don’t know what punk rock is, and we don’t know what that scene is all about, but God bless you.’” Sadly, the saga of the miners in Stearns ended in defeat during May 1979, when they lost their long-awaited representation election. Ultimately, the odyssey of the Stearns miners’ preceded and outlasted the first-wave punk scene in San Francisco!

“These workers are on strike because they have legitimate, urgent grievances directly affecting their safety, health and livelihood. And the mine owners, whose profits have risen by 800 percent in the last ten years, are trying to undermine a basic and essential American right—the right to strike. This is not Russia, where it’s a crime to strike—not yet, anyway.” —Chip Kinman (Dils), March 1978

During the long gestation period of this project, it was eerie to witness our country’s return to issues and topics from the late ’70s, and the miners’ strike, in particular. This time California endured a disastrous energy crisis, and once again a U.S. President invoked federal powers to end a labor dispute. Reacting to an eleven-day port shutdown during Fall 2002—a conflict between the Pacific Maritime Association and workers belonging to the International Longshore and Warehouse Union—President George W. Bush invoked the Taft-Hartley Act (used for the first time since Jimmy Carter's intervention in the '77-78 coal miners' strike) on October 8 to force a resumption of work. But this time, in a perverse twist, Taft-Hartley was invoked not to end a strike, but an employer lockout.

As these notes are written the United States is at war in the Mideast, which seemed a likely prospect during President Carter's term (remember the U.S. hostage crisis in Iran?). Once again, cultural revolt is in the air. Our national pop music scene is distressingly similar to the late '70s, as the U.S. music industry churns out escapist product for mass consumption. There are also new forms of mindless disco assaulting our ears. Give this music from the Miners' Benefit a listen (U.X.A., Sleepers, Negative Trend, Tuxedomoon), critical or otherwise, and feel the energy to express yourself. Do so, or else we are condemned to repeat our collective past, and you don’t want that—take my word. We’ve had enough of that lately.

What Alan Freed’s rock’n’roll was in 1959—the teenager’s own healthy symbol of rebellion—punk rock is today. And today the guardians of the status quo are fighting it as doggedly as they were then.” —Howie Klein, 1978