Candlestick Before and After Stadium Built: Difference between revisions

(upgraded photo and caption and changed decade) |

(upgraded photo and caption and changed decade) |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

[[Image:Bayview-Hill-and-surroundings-from-air-1957 3003.jpg|720px|thumb]] | [[Image:Bayview-Hill-and-surroundings-from-air-1957 3003.jpg|720px|thumb]] | ||

'''Candlestick Point, 1957, same view as above, | '''Candlestick Point, 1957, same view as above, 29 years later, with a good deal of construction and landfilling underway.''' | ||

''Photo: San Francisco Planning Commission'' | ''Photo: San Francisco Planning Commission'' | ||

Latest revision as of 14:24, 4 January 2020

Historical Essay

by Wade Avery, 2013

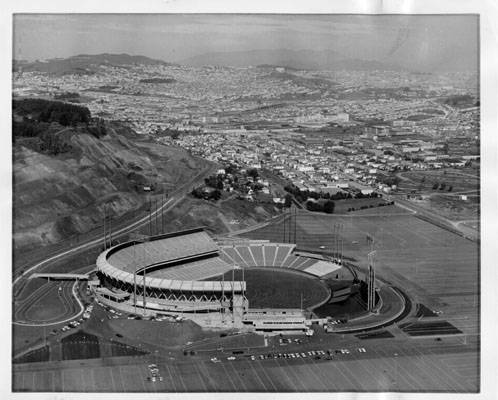

Candlestick Park on Opening Day 1960, its inaugural season as the San Francisco Giants home park.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/mVqQDe7osWc" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Candlestick Park, aerials 1962

Video: Prelinger Archives home movies

Candlestick Park and its Community Legacy

The Bayview-Hunters Point community of San Francisco is one that has had an incredibly diverse history and has experienced multiple dramatic changes in the geography, demographics, and economy over the course of the past century and a half. Located in the southeast corner of San Francisco County, Bayview-Hunters Point (BVHP) was once covered with grass fields and marshlands on the water’s edge. Yet, as the city of San Francisco began to boom, especially during the era of the gold rush in the mid-1800s, the population and industries began to spill over into the previously undeveloped area south of the city. Initially, the primary industry brought to the BVHP area were slaughterhouses, which would be used to produce wool, fertilizer, and package meat.(1) Because San Francisco city ordinance prevented slaughterhouses from being located within the city limits in 1868, 18 slaughterhouses popped up in the BVHP area and provided a major increase in low wage job opportunities south of the city.(2) However, when the slaughterhouse industry began to decline following the 1906 earthquake, another industry took BVHP by storm—shipbuilding.

The first permanent dry dock on the west coast Pacific coast of the U.S., located at Hunters Point, provided even more job opportunities that brought more people down from the city and into the BVHP. As America entered World War I and World War II, the Navy invested heavily in the bustling shipyards in BVHP as there was a skyrocketing demand for the construction of large warships for the formidable Pacific Fleet.(3) This increased demand for labor in the shipyards brought even more dramatic change in the demographic make up of BVHP. Many African Americans from the south flooded into BVHP during “The Great Migration,” when many African Americans relocated to the North and the West in order to escape the segregation of the south. As a result of this massive relocation, the population of BVHP quadrupled between 1940 and 1950 to 51,000 residents, with African Americans becoming a growing portion of the population.(4) As WWII drew to a close, it became apparent that BVHP was becoming a Black community and many of the white workers of European descent who had previously populated the community began to find homes elsewhere, as many of the African Americans in the city were forced out of their homes and relocated in BVHP. The community eventually became segregated from the rest of the city, with little new business or population growth being experienced.(5)

However, in August of 1958 the community saw an opportunity to grow it hadn’t seen in over a decade, the construction of a new stadium for the San Francisco Giants baseball team right in the BVHP community. The park, which was initially designed to hold 43,000 spectators, injected life into a community that had begun to struggle with employment following the downturn of the slaughterhouse and shipbuilding industries.(6) On April 12, 1960, Candlestick Park opened its gates and with it came hope that the stadium would lead to more jobs and development in the area around the stadium. Built only a few years after the stadium in 1962, the Alice Griffith Public Housing Project was built to provide low-income housing to up to 250 families and provide a place for workers near the stadium to live.(7) In 1971, the stadium got an additional boost from the addition of the San Francisco 49ers football franchise relocating to Candlestick Park. With the addition of a new team, the stadium was expanded for the sixth time in 11 years, bringing the capacity to 61,000 spectators.(8) Over the coming 50 years Candlestick Park would become a major landmark in the city as the two professional franchises experienced success, with the 49ers winning five Super Bowls and the Giants winning four West Division titles and one NL Pennant.

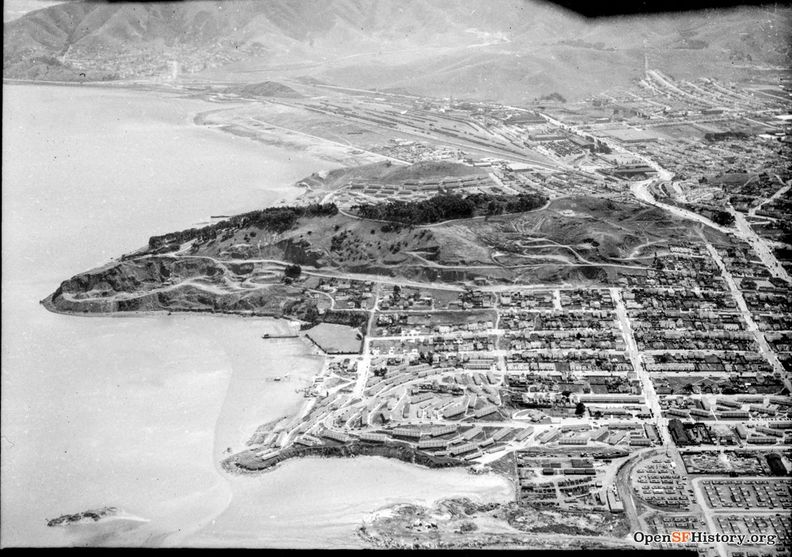

Candlestick Point, 1928, looking generally south towards San Bruno Mountain and the town of Brisbane. No ballpark, not even the land to build it on is yet present.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp28.1151; courtesy private collector, San Francisco,CA

Candlestick Point, 1957, same view as above, 29 years later, with a good deal of construction and landfilling underway.

Photo: San Francisco Planning Commission

But while the teams shined in the stadium, the stadium itself had numerous shortcomings with its design, which made it in some ways obsolete and an undesirable location for fans. Its bayside location made it susceptible to some of the highest winds in the city, thick fog, and cold temperatures.(9) Additionally, the ineffective radiant heating system and the distance of the seats from the field made it an unpleasant experience for many fans. These unwelcoming conditions resulted in lower attendance and no desire for the fans to stay in the area any longer than they needed to.(10) This played a role in stunting the development of any surrounding commercial entities such as bars and restaurants that would bring fans to stay in the area longer and spend more money in the local community. The surrounding area was also tainted by contamination left behind by the National Radiology Defense Laboratory, which polluted much of the area around the shipyard with toxic waste, essentially turning it into a ghost town. With little interest or opportunity for development in the community surrounding the stadium, Candlestick Park already appeared to have a quite limited impact in BVHP.(11)

When the Hunters Point Shipyard was decommissioned by the Navy in 1974, the community found itself facing a multitude of problems that would plunge the community into poverty and struggle. At the forefront, was a glaring rise in unemployment, which Candlestick Park was unable to assist. Because the stadium only provided seasonal jobs that could only support employees for short spans of time, Candlestick Park had very little to no impact in helping ease the effect of the Shipyard closure on the community. When the park opened in 1960, the unemployment in BVHP was at 3.8%. But over the years of Candlestick Park’s presence in the community, the unemployment in BVHP only rose, reaching 7.3% in 1970 and 12.4% in 1980, which doubled the unemployment of the rest of the metropolitan area.(12) This rising unemployment coincided with a dramatic increase in crime throughout the area. During the 1980s, the crack epidemic hit the BVHP community hard, leading to a major increase in drug trafficking, gang violence, and violent crime.(13) Despite only having 5% of the city’s population, BVHP has consistently accounted for up to 30% of the homicides in the city.(14) The temporary nature of the jobs offered at Candlestick Park and the inability for sufficient development in the surrounding area made the stadium of little economic value to the surrounding community and became viewed as an ineffective asset in providing opportunity to the community and snubbing the rising unemployment and crime.

This is clearly evident by the peaking numbers of crime and poverty since the turn of the century. In 2004, BVHP accounted for 50% of the homicides in San Francisco and in the 2000 census it was recorded that a large section of the community, which includes the Hunters Point and Alice Griffith housing projects, had 53.4% of its citizens living below the poverty line, with unemployment at 22%.(15) With the stadium becoming ever outdated with each passing year, it became evident that the 49ers would relocate their team and any remaining hopes for redevelopment were all but unrealistic.

All of these statistics reveal that Candlestick Park, which is to be torn down in 2014 following the departure of the 49ers, failed to have any sort of positive impact on the struggling surrounding community and was an inadequate economic entity in providing jobs and bringing in money to the BVHP community. The stadium was unable to break the burdening effect that shipyard and its subsequent closure had on the community. However, the community has been making progress, with plans to replace Candlestick Park with assets such as parks and newer housing developments that will be much more valuable to the community than the obsolete stadium that existed before.(16) While the rest of the city may view Candlestick Park as a major piece of Bay Area sports history and a landmark in the city, those who lived in the shadow of the concrete mammoth will remember the park as an ineffective tool for economic progress within the community and an afterthought in a community in needs of real solutions for revival and redevelopment in the future.

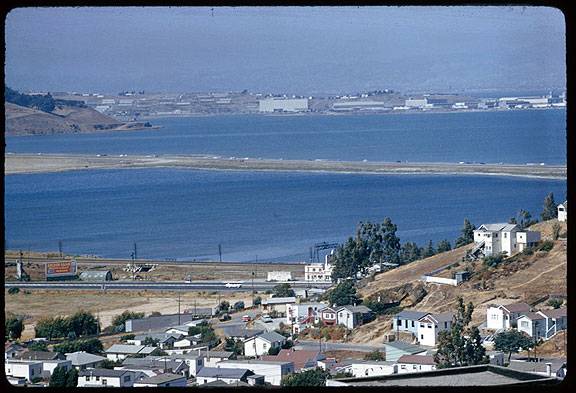

July 20, 1957: Highway 101 causeway with Brisbane Lagoon in foreground. Note Bayview Hill with no Candlestick landfill or stadium, nor does Candlestick Point State Recreation Area exist yet.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P09410)

Candlestick Park after its completion in 1960.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

View southward from Hunter's Point, 1997.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

View south across Yosemite Slough towards former stadium site, August 2015.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Candlestick Point under Bayview Hill, the State Recreation Center extending eastward into the bay, 2015.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Notes

1. VerPlanck, Kelley. "Bayview-Hunters Point Historical Context Statement." San Francisco Redevelopment Agency 1 (2010). http://bayviewmagic.org/files/2010/02/History-of-BVHP.pdf (accessed June 8, 2013).

2. VerPlanck, Kelley. "Bayview-Hunters Point Historical Context Statement." San Francisco Redevelopment Agency 1 (2010). http://bayviewmagic.org/files/2010/02/History-of-BVHP.pdf (accessed June 8, 2013).

3. Finch, Kelsey. "Trouble In Paradise: Postwar History of San Francisco's Hunters Point Neighborhood." Program on Urban Studies. http://urbanstudies.stanford.edu (accessed June 8, 2013).

4. Jeffries, Amy. "Profile: Bayview-Hunters Point." Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. http://journalism.berkeley.edu (accessed June 8, 2013).

5. Bowser, Benjamin. "Bayview-Hunter's Point: San Francisco's Black Ghetto Revisited." Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 17 (1988). http://www.jstor.org/stable/40553136 (accessed June 8, 2013).

6. Leong, Ryan. "The History of Candlestick Park." The Examiner (San Francisco), February 12, 2013. http://www.examiner.com/review/the-history-of-candlestick-park (accessed June 8, 2013).

7. "Alternatives For Study." Bionic Planning 1 (2009): 6-23. http://www.arcecology.org (accessed June 8, 2013).

8. Leong, Ryan. "The History of Candlestick Park." The Examiner (San Francisco), February 12, 2013. http://www.examiner.com/review/the-history-of-candlestick-park (accessed June 8, 2013).

9. "Alternatives For Study." Bionic Planning 1 (2009): 6-23. http://www.arcecology.org (accessed June 8, 2013).

10. "Alternatives For Study." Bionic Planning 1 (2009): 6-23. http://www.arcecology.org (accessed June 8, 2013).

11. Jacobson, Daniel. "A History of Bayview-Hunters Point, Part 2: Crime, Contamination, and Crisis | 21st Century Urban Solutions." 21st Century Urban Solutions. http://21stcenturyurbansolutions.com (accessed June 8, 2013).

12. Finch, Kelsey. "Trouble In Paradise: Postwar History of San Francisco's Hunters Point Neighborhood." Program on Urban Studies. http://urbanstudies.stanford.edu (accessed June 8, 2013).

13. Jeffries, Amy. "Profile: Bayview-Hunters Point." Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. http://journalism.berkeley.edu (accessed June 8, 2013).

14. Jacobson, Daniel. "A History of Bayview-Hunters Point, Part 2: Crime, Contamination, and Crisis | 21st Century Urban Solutions." 21st Century Urban Solutions. http://21stcenturyurbansolutions.com (accessed June 8, 2013).

15. Jacobson, Daniel. "A History of Bayview-Hunters Point, Part 2: Crime, Contamination, and Crisis | 21st Century Urban Solutions." 21st Century Urban Solutions. http://21stcenturyurbansolutions.com (accessed June 8, 2013).

16. Wall Street Journal. "Big Plans for the Neighborhood in Post-Candlestick Era ." Wall Street Journal (New York), March 6, 2013. http://online.wsj.com (accessed June 8, 2013).