Automobiles Take Over San Francisco Streets: Difference between revisions

(Created page with ''''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' ''by Chris Carlsson'' Originally published at [http://sf.streetsblog.org...') |

(fixed formatting on photos) |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | ||

[[Image:Motorland-cover-1927 3043.jpg| | [[Image:Motorland-cover-1927 3043.jpg|400px|right]] | ||

It’s almost impossible to imagine the speed with which conditions on urban streets changed at the dawn of the motorized era. Here’s a quote from the California Automobile Association’s Motorland magazine in August 1927 describing the rapid growth in car ownership: | For decades, over 40,000 people have died each year in car crashes on the streets of the United States. This daily carnage is utterly normalized to the point that few of us think about it at all, and if we do, it’s like the weather, just a regular part of our environment. But it wasn’t always this way. Back when the private automobile was first beginning to appear on public streets a large majority of the population, including politicians, police, and business leaders, agreed that cars were interlopers and ought to be regulated and subordinated to pedestrians and streetcars. | ||

It’s almost impossible to imagine the speed with which conditions on urban streets changed at the dawn of the motorized era. Here’s a quote from the California Automobile Association’s ''Motorland'' magazine in August 1927 describing the rapid growth in car ownership: | |||

<blockquote>In 1895 there were four cars registered, in 1905 there were 77,400 in use, in 1915 the total had risen to 2,309,000, and in 1925 there were 17,512,000 passenger automobiles on the highways, and the total is now in excess of 20,000,000.</blockquote> | <blockquote>In 1895 there were four cars registered, in 1905 there were 77,400 in use, in 1915 the total had risen to 2,309,000, and in 1925 there were 17,512,000 passenger automobiles on the highways, and the total is now in excess of 20,000,000.</blockquote> | ||

| Line 29: | Line 31: | ||

With over two million cars clogging city streets in 1915, and death and injury tolls rising, cities took various measures to address the problem (quoting from “Fighting Traffic”): | With over two million cars clogging city streets in 1915, and death and injury tolls rising, cities took various measures to address the problem (quoting from “Fighting Traffic”): | ||

[[Image:Market st pedestrians 1937 AAB-6406.jpg|right|240px | [[Image:Market st pedestrians 1937 AAB-6406.jpg|right|240px]] | ||

'''Pedestrians on Market Street, 1937''' | |||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | |||

<blockquote>From 1915 (and especially after 1920), cities tried marking crosswalks with painted lines, but most pedestrians ignored them. A Kansas City safety expert reported that when police tried to keep them out of the roadway, “pedestrians, many of them women” would “demand that police stand aside.” In one case, he reported, “women used their parasols on the policemen.” Police relaxed enforcement.</blockquote> | |||

The common usage of the streets by all was considered sacrosanct and attempts by motordom and/or police to regulate people’s use of the streets was widely resisted. Plenty of police didn’t agree that pedestrian behavior should be criminalized on behalf of motoring: | The common usage of the streets by all was considered sacrosanct and attempts by motordom and/or police to regulate people’s use of the streets was widely resisted. Plenty of police didn’t agree that pedestrian behavior should be criminalized on behalf of motoring: | ||

| Line 78: | Line 86: | ||

<blockquote>There was no “buying-power saturation,” [Motordom] said. The real bridle on the demand for automobiles was not the consumer’s wallet, but street capacity. Traffic congestion deterred the would-be urban car buyer, and congestion was saturation of streets.</blockquote> | <blockquote>There was no “buying-power saturation,” [Motordom] said. The real bridle on the demand for automobiles was not the consumer’s wallet, but street capacity. Traffic congestion deterred the would-be urban car buyer, and congestion was saturation of streets.</blockquote> | ||

[[Image:Sidewalks-reduced-to-12-ft-Howard-Street-betw-24th-25th-aug-1921.jpg]] | |||

'''Photo in August 1921 right after sidewalks on Howard (now South Van Ness) between 24th and 25th Streets had been reduced to 12 feet wide.''' | |||

''Photo: SFMTA'' | |||

By the late 1920s, a young graduate student named Miller McClintock had become the nation’s pre-eminent traffic researcher thanks to his 1925 thesis “Street Traffic Control.” His career is a window into the process of private corruption of public interests that riddles American history up to the present. | By the late 1920s, a young graduate student named Miller McClintock had become the nation’s pre-eminent traffic researcher thanks to his 1925 thesis “Street Traffic Control.” His career is a window into the process of private corruption of public interests that riddles American history up to the present. | ||

| Line 87: | Line 101: | ||

What had happened in the two years between the diametrically opposed advice given by McClintock? He had been hired by Studebaker’s Vice President to head up the new “Albert Russel Erskine Bureau for Street Traffic Research,” which was first placed in Los Angeles where McClintock was teaching at UC, but a year later moved by Studebaker to Harvard University, where the car company continued to fund the ostensibly “independent” institute. As the years went by McClintock became one of the foremost authorities on traffic planning, though his organization dropped the “Albert Russel Erskine” from its name when the chairman of Studebaker Motors committed suicide in 1933! | What had happened in the two years between the diametrically opposed advice given by McClintock? He had been hired by Studebaker’s Vice President to head up the new “Albert Russel Erskine Bureau for Street Traffic Research,” which was first placed in Los Angeles where McClintock was teaching at UC, but a year later moved by Studebaker to Harvard University, where the car company continued to fund the ostensibly “independent” institute. As the years went by McClintock became one of the foremost authorities on traffic planning, though his organization dropped the “Albert Russel Erskine” from its name when the chairman of Studebaker Motors committed suicide in 1933! | ||

[[Image:Automobile dealership at Van Ness Avenue and Geary Street apr 18 1923 AAD-4651.jpg]] | |||

'''Auto dealership at Van Ness Avenue and Geary Street, April 18, 1923.''' | |||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | |||

[[Image:Van-Ness-south-from-Sacramento-Auto-Row-1930 72dpi.jpg|720px]] | |||

'''Van Ness Avenue looking south from Sacramento, Auto Row stretching for blocks in 1930, First Presbyterian Church at left.''' | |||

'' | ''Photo: C.R. collection'' | ||

[[Image:John-Gutmann-Cut-Your-Speed 1935 -2000.111.19.jpg]] | |||

'''1935 public campaign by SF Police against speeding motorists.''' | |||

'' | ''Photo: John Gutmann'' | ||

McClintock came to San Francisco early in his career. In the August 1927 Motorland magazine, he penned an article summarizing his research “Curing the Ills of San Francisco Traffic”: “… it is recognized that an ultimate requirement for the solution of street and highway congestion is to be found in the creation of more ample street area.” And sure enough, it was in this exact period that San Francisco embarked on a series of street widenings throughout the city, including for example, Capp Street and [[A Brief History of Cesar Chavez/Army Street|Army Street]] in the Mission District. Interestingly, McClintock’s traffic study shows the predominant car-free life of San Franciscans at the time: | |||

[ | <blockquote>On a typical business day studied by the traffic survey committee, 1,073,963 persons entered and left [the central business] district during a fourteen-hour period from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. Vehicles of all types, including streetcars, carried 744,667 people in and out of the district, In addition, 329,296 pedestrians entered and left the district during the same period… In no other city is there such a large pedestrian movement into the central district, nor such a large outrush of people during the noon hour. Both of these conditions may be attributed to the large capacity of apartment houses immediately adjacent to the district…</blockquote> | ||

Incredibly, streetcars were used by 70 percent of the people depending on some kind of transportation to get downtown, while only a quarter used passenger cars, but the latter made up 61 percent of vehicular traffic as compared to 11 percent for the streetcars! What has been poorly understood in the triumphant narrative of the private automobile is how cars benefited from enormous public expenditures, even when they were being used by a relatively small minority of the population. New infrastructure to accommodate motorists far outstripped any public investment in public streetcar service, let alone any subsidies for the privately owned lines. Meanwhile, electric streetcar companies were slowly going bankrupt, with their fares publicly restricted and the public streets on which they operated slowly being taken over by private vehicles. | |||

[[ | Traditional use of the streets by pedestrians was being criminalized by new traffic codes. McClintock put forth a new Uniform Traffic Ordinance, adopted by San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, which was intended to “legislate jaywalkers off the streets,” crowed a ''Motorland'' magazine editorial. In 1915, Ford already had a [[Harrison Street Industrial Corridor|factory at 21st and Harrison]] in the Mission making Model-T’s, and by the mid-1920s, the [[Auto Row on Van Ness|new car business]] was fully ensconced along Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco. | ||

Miller McClintock continued his work on behalf of the auto industry from his bought-and-paid-for perch at Harvard University. | Miller McClintock continued his work on behalf of the auto industry from his bought-and-paid-for perch at Harvard University. | ||

| Line 138: | Line 146: | ||

Here’s a description of the exhibit by Richard Reinhart in his book on the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition “Treasure Island: San Francisco’s Exposition Years” | Here’s a description of the exhibit by Richard Reinhart in his book on the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition “Treasure Island: San Francisco’s Exposition Years” | ||

[[Image:Cadillac dealership August 1964 AAD-4658.jpg|right]] | |||

'''1964 image of Cadillac dealership''' | |||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | |||

<blockquote>Artist Donald McLoughlin had prepared a dioramic view of San Francisco in 1999 for the US Steel exhibit in the Hall of Mines, Metals and Machinery. This prognostic nightmare showed the city stripped of every vestige of 1939 except Coit Tower, the bridges and Chinatown. All maritime activity had disappeared from the Embarcadero. Shipping was concentrated at a super-pier at the foot of 16th Street. | <blockquote>Artist Donald McLoughlin had prepared a dioramic view of San Francisco in 1999 for the US Steel exhibit in the Hall of Mines, Metals and Machinery. This prognostic nightmare showed the city stripped of every vestige of 1939 except Coit Tower, the bridges and Chinatown. All maritime activity had disappeared from the Embarcadero. Shipping was concentrated at a super-pier at the foot of 16th Street. | ||

| Line 143: | Line 157: | ||

North of Market Street every block contained a single, identical high-rise apartment house. South of Market, sixty-story office towers of steel and glass alternated with block-square plazas in a vast checkerboard pattern. Elevated freeways ran through the geometric landscape.</blockquote> | North of Market Street every block contained a single, identical high-rise apartment house. South of Market, sixty-story office towers of steel and glass alternated with block-square plazas in a vast checkerboard pattern. Elevated freeways ran through the geometric landscape.</blockquote> | ||

McLoughlin correctly anticipated the removal of maritime activity from San Francisco’s waterfront, though his massive modern pier is spread along the Oakland bay shore rather than on a prominent pier jutting out from 16th Street. Visions like this, and the better known version in New York, informed the post-WWII population as it fled cities for the suburbs. Those who remained though, had a different idea of what our cities would become, and thanks to their stopping the highway builders in their tracks in the late 1950s and early 1960s, San Francisco was not crushed in this way. | |||

Interesting to recall that while 30,000 citizens were mobilized to [[The Freeway Revolt|stop freeway building]] in San Francisco (the very same elevated, pedestrian-free streets McClintock had come to endorse as an industry flack) thousands more, mostly African American and white youth, staged a vigorous [[Segregation_and_the_Civil_Rights_Movement_in_San_Francisco|civil rights campaign]] along auto row, demanding that blacks be given equal treatment in hiring by auto dealers, especially Don Lee’s Cadillac dealership. | Interesting to recall that while 30,000 citizens were mobilized to [[The Freeway Revolt|stop freeway building]] in San Francisco (the very same elevated, pedestrian-free streets McClintock had come to endorse as an industry flack) thousands more, mostly African American and white youth, staged a vigorous [[Segregation_and_the_Civil_Rights_Movement_in_San_Francisco|civil rights campaign]] along auto row, demanding that blacks be given equal treatment in hiring by auto dealers, especially Don Lee’s Cadillac dealership. | ||

| Line 157: | Line 171: | ||

[[ | [[TRANSIT INTRODUCTION |Prev. Document]] [[Transbay Terminal|Next Document]] | ||

[[category:Transit]] [[category:1900s]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:2000s]] [[category:roads]] | [[category:Transit]] [[category:1900s]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:2000s]] [[category:roads]] [[category:Polk Gulch]] [[category:Downtown]] [[category:Civic Center]] | ||

Latest revision as of 18:39, 5 May 2020

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

Originally published at sf.streetsblog.org as Whose Streets?

Market and Kearny and 3rd Streets, 1909.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

“Whose Streets? OUR Streets!” yell rowdy demonstrators when they surge off the sidewalk and into thoroughfares. True enough, the streets are our public commons, what’s left of it (along with libraries and our diminishing public schools), but most of the time these public avenues are dedicated to the movement of vehicles, mostly privately owned autos. Other uses are frowned upon, discouraged by laws and regulations and what has become our “customary expectations.” Ask any driver who is impeded by anything other than a “normal” traffic jam and they’ll be quick to denounce the inappropriate use or blockage of the street.

Bicyclists have been working to make space on the streets of San Francisco for bicycling, and to do that they’ve been trying to reshape public expectations about how streets are used. Predictably there’s been a pushback from motorists and their allies, who imagine that the norms of mid-20th century American life can be extended indefinitely into the future. But cyclists and their natural allies, pedestrians, can take heart from a lost history that has been illuminated by Peter D. Norton in his recent book Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City. He skillfully excavates the shift that was engineered in public opinion during the 1920s by the organized forces of what called itself “Motordom.” Their efforts turned pedestrians into scofflaws known as “jaywalkers,” shifted the burden of public safety from speeding motorists to their victims, and reorganized American urban design around providing more roads and more space for private cars.

Typical street scene in 1909, long before private cars had become a major problem.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

For decades, over 40,000 people have died each year in car crashes on the streets of the United States. This daily carnage is utterly normalized to the point that few of us think about it at all, and if we do, it’s like the weather, just a regular part of our environment. But it wasn’t always this way. Back when the private automobile was first beginning to appear on public streets a large majority of the population, including politicians, police, and business leaders, agreed that cars were interlopers and ought to be regulated and subordinated to pedestrians and streetcars.

It’s almost impossible to imagine the speed with which conditions on urban streets changed at the dawn of the motorized era. Here’s a quote from the California Automobile Association’s Motorland magazine in August 1927 describing the rapid growth in car ownership:

In 1895 there were four cars registered, in 1905 there were 77,400 in use, in 1915 the total had risen to 2,309,000, and in 1925 there were 17,512,000 passenger automobiles on the highways, and the total is now in excess of 20,000,000.

With over two million cars clogging city streets in 1915, and death and injury tolls rising, cities took various measures to address the problem (quoting from “Fighting Traffic”):

Pedestrians on Market Street, 1937

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

From 1915 (and especially after 1920), cities tried marking crosswalks with painted lines, but most pedestrians ignored them. A Kansas City safety expert reported that when police tried to keep them out of the roadway, “pedestrians, many of them women” would “demand that police stand aside.” In one case, he reported, “women used their parasols on the policemen.” Police relaxed enforcement.

The common usage of the streets by all was considered sacrosanct and attempts by motordom and/or police to regulate people’s use of the streets was widely resisted. Plenty of police didn’t agree that pedestrian behavior should be criminalized on behalf of motoring:

New York police magistrate Bruce Cobb in 1919 defended the “legal right to the highway” of the “foot passenger,” arguing that “if pedestrians were at their peril confined to street corners or certain designated crossings, it might tend to give selfish drivers too great a sense of proprietorship in the highway.” He assigned the responsibility for the safety of the pedestrian—even one who “darts obliquely across a crowded thorofare”—to drivers… By 1916 “jaywalker” was a feature of “police parlance.” Police use modified the word’s meaning and sparked controversy. “Jaywalker” carried the sting of ridicule, and many objected to branding independent-minded pedestrians with the term… The New York Times objected, calling the word “highly opprobrious” and “a truly shocking name.”

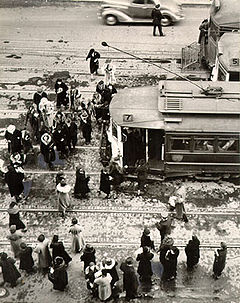

Anti-jaywalking campaigns came to San Francisco too.

In a 1920 safety campaign, San Francisco pedestrians who thought they were minding their own business found themselves pulled into mocked-up outdoor courtrooms. In front of crowds of onlookers they were lectured on the perils of jaywalking.

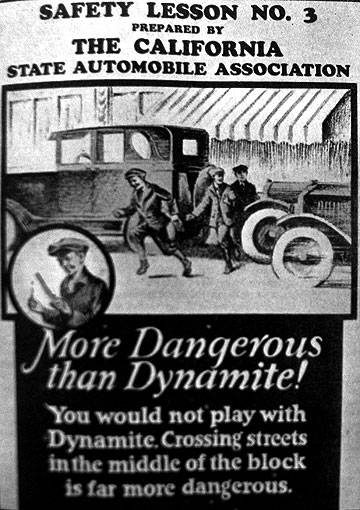

Typical of auto industry-sponsored advertising shifting the burden for road safety from motorists to the children who had customarily been able to play in the streets safely. (Motorland magazine)]]

In 1941 jaywalking became a topic of interest in local papers, with several images captured of women jaywalking.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Clearly 20 years of anti-jaywalking campaigns in San Francisco and the country as a whole had not convinced people to abandon their customary ways of crossing public streets.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

In 1942 this shot at 5th and Market shows the women walking against the signal.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

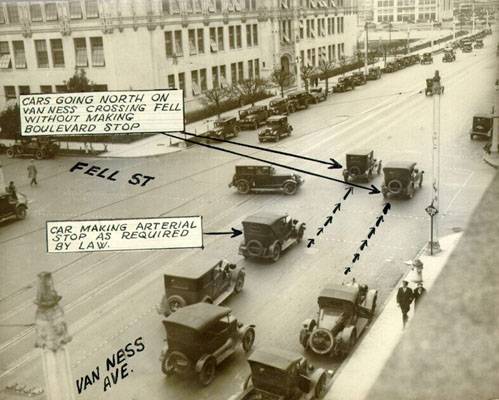

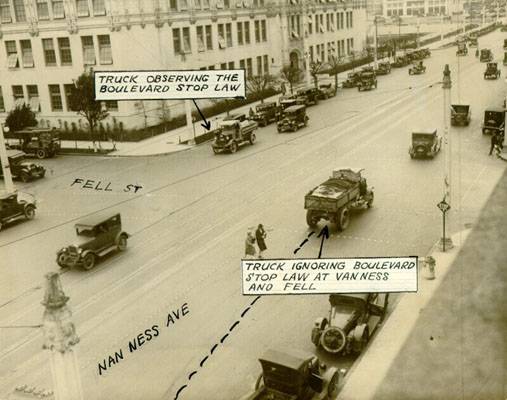

As the 1920s continued, more and more cars were being sold, and the streets were both crowded and contested. Streetcar operators blamed cars for clogging thoroughfares and slowing down their lines, causing late runs and generally inconveniencing passengers. Motorists parked everywhere, jamming curbsides two-deep, when they weren’t weaving through chaotic urban streets. Attempts to regulate and standardize traffic patterns began during this era, with lanes, crosswalks, traffic signals, and parking regulations slowly emerging as “solutions” to the problems created by tens of thousands of private cars filling the streets.

February 3, 1927, Van Ness and Fell Streets, with helpful labels to show what motorists are doing wrong.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

More 1927 instructional photography.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

When sales slumped in late 1923 and into 1924, analysts speculated that the market for cars was saturated (at about 7 Americans per car at the time). The car industry consisted of dozens of companies, who began to fail or merge during this first contraction in sales. The industry reorganized its public relations and launched concerted efforts to redefine “saturation”:

There was no “buying-power saturation,” [Motordom] said. The real bridle on the demand for automobiles was not the consumer’s wallet, but street capacity. Traffic congestion deterred the would-be urban car buyer, and congestion was saturation of streets.

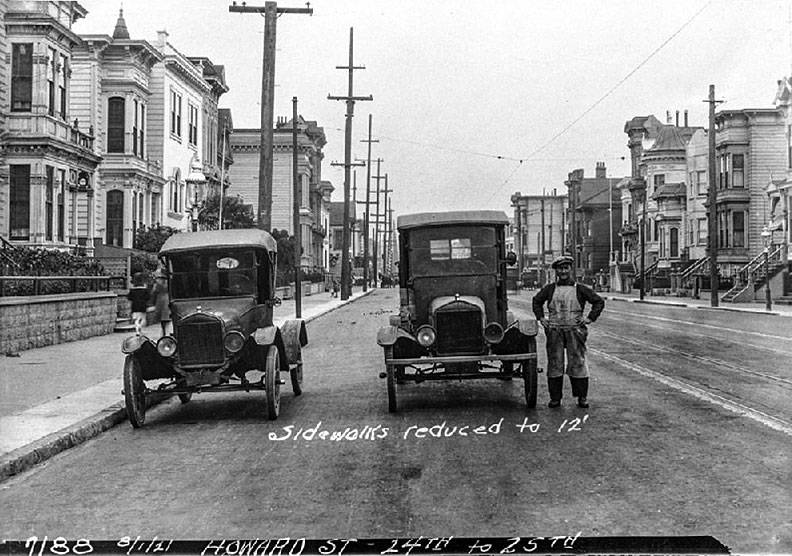

Photo in August 1921 right after sidewalks on Howard (now South Van Ness) between 24th and 25th Streets had been reduced to 12 feet wide.

Photo: SFMTA

By the late 1920s, a young graduate student named Miller McClintock had become the nation’s pre-eminent traffic researcher thanks to his 1925 thesis “Street Traffic Control.” His career is a window into the process of private corruption of public interests that riddles American history up to the present.

In his 1925 graduate thesis Street Traffic Control, the old McClintock had maintained that widening streets would merely attract more vehicles to them, leaving traffic as congested as before. The automobile, he wrote, was a waster of space compared to the streetcar, noting that “the greater economy of the latter is marked.” “It seems desirable,” McClintock wrote, “to give trolley cars the right of way under general conditions, and to place restrictions on motor vehicles in their relations with street cars.” He described the automobile as a “menace to human life” and “the greatest public destroyer of human life.” Two years later all had changed. McClintock wrote of “the inevitable necessity to provide more room” in the streets. He called for “new streets” and “wider streets.”… In 1925 McClintock virtually ruled out elevated streets as expensive and impractical; two years later he urged that they be considered.

What had happened in the two years between the diametrically opposed advice given by McClintock? He had been hired by Studebaker’s Vice President to head up the new “Albert Russel Erskine Bureau for Street Traffic Research,” which was first placed in Los Angeles where McClintock was teaching at UC, but a year later moved by Studebaker to Harvard University, where the car company continued to fund the ostensibly “independent” institute. As the years went by McClintock became one of the foremost authorities on traffic planning, though his organization dropped the “Albert Russel Erskine” from its name when the chairman of Studebaker Motors committed suicide in 1933!

Auto dealership at Van Ness Avenue and Geary Street, April 18, 1923.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Van Ness Avenue looking south from Sacramento, Auto Row stretching for blocks in 1930, First Presbyterian Church at left.

Photo: C.R. collection

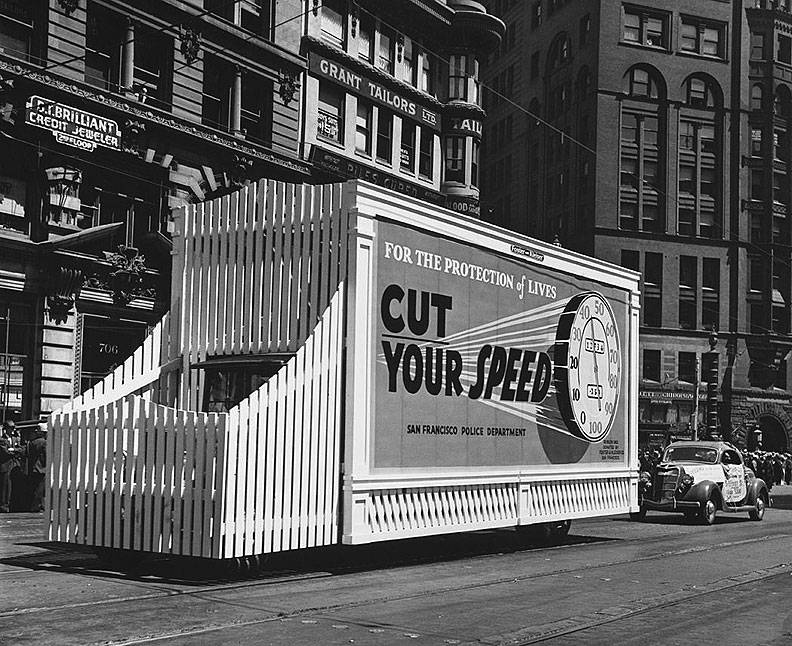

1935 public campaign by SF Police against speeding motorists.

Photo: John Gutmann

McClintock came to San Francisco early in his career. In the August 1927 Motorland magazine, he penned an article summarizing his research “Curing the Ills of San Francisco Traffic”: “… it is recognized that an ultimate requirement for the solution of street and highway congestion is to be found in the creation of more ample street area.” And sure enough, it was in this exact period that San Francisco embarked on a series of street widenings throughout the city, including for example, Capp Street and Army Street in the Mission District. Interestingly, McClintock’s traffic study shows the predominant car-free life of San Franciscans at the time:

On a typical business day studied by the traffic survey committee, 1,073,963 persons entered and left [the central business] district during a fourteen-hour period from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. Vehicles of all types, including streetcars, carried 744,667 people in and out of the district, In addition, 329,296 pedestrians entered and left the district during the same period… In no other city is there such a large pedestrian movement into the central district, nor such a large outrush of people during the noon hour. Both of these conditions may be attributed to the large capacity of apartment houses immediately adjacent to the district…

Incredibly, streetcars were used by 70 percent of the people depending on some kind of transportation to get downtown, while only a quarter used passenger cars, but the latter made up 61 percent of vehicular traffic as compared to 11 percent for the streetcars! What has been poorly understood in the triumphant narrative of the private automobile is how cars benefited from enormous public expenditures, even when they were being used by a relatively small minority of the population. New infrastructure to accommodate motorists far outstripped any public investment in public streetcar service, let alone any subsidies for the privately owned lines. Meanwhile, electric streetcar companies were slowly going bankrupt, with their fares publicly restricted and the public streets on which they operated slowly being taken over by private vehicles.

Traditional use of the streets by pedestrians was being criminalized by new traffic codes. McClintock put forth a new Uniform Traffic Ordinance, adopted by San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, which was intended to “legislate jaywalkers off the streets,” crowed a Motorland magazine editorial. In 1915, Ford already had a factory at 21st and Harrison in the Mission making Model-T’s, and by the mid-1920s, the new car business was fully ensconced along Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco.

Miller McClintock continued his work on behalf of the auto industry from his bought-and-paid-for perch at Harvard University.

Miller McClintock [became] the impresario of a new kind of highway road show. In the spring of 1937, the Shell Oil Company combined McClintock’s traffic expertise with the talents of the stage designer Normal Bel Geddes to build a scale model of “the automobile city of tomorrow.”… Others interested in the rebuilding of cities for the motor age adopted Shell’s technique. At the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition, United States Steel displayed its vision of San Francisco in 1999, with wider streets, cloverleaf intersections, and an elevated highway.

Overshadowed by the far more successful World’s Fair in New York City, and in particular by the tone-setting “World of Tomorrow” exhibit there built by General Motors, the 1939 US Steel vision of San Francisco in 1999 is worth peeking at:

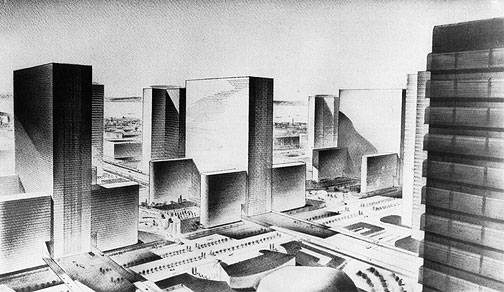

"San Francisco in 1999" Golden Gate International Exposition, 1939. US Steel financed this diorama, meant to reinvent San Francisco as a Corbusian radial city with a new rationalized and centralized port combining all piers in a single monumental jetty extending from 16th Street.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

This close-up from the US Steel 1939 vision of San Francisco in 1999 shows the intersection of 7th and Howard streets with elevated roadways passing under each tower.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Here’s a description of the exhibit by Richard Reinhart in his book on the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition “Treasure Island: San Francisco’s Exposition Years”

1964 image of Cadillac dealership

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Artist Donald McLoughlin had prepared a dioramic view of San Francisco in 1999 for the US Steel exhibit in the Hall of Mines, Metals and Machinery. This prognostic nightmare showed the city stripped of every vestige of 1939 except Coit Tower, the bridges and Chinatown. All maritime activity had disappeared from the Embarcadero. Shipping was concentrated at a super-pier at the foot of 16th Street. North of Market Street every block contained a single, identical high-rise apartment house. South of Market, sixty-story office towers of steel and glass alternated with block-square plazas in a vast checkerboard pattern. Elevated freeways ran through the geometric landscape.

McLoughlin correctly anticipated the removal of maritime activity from San Francisco’s waterfront, though his massive modern pier is spread along the Oakland bay shore rather than on a prominent pier jutting out from 16th Street. Visions like this, and the better known version in New York, informed the post-WWII population as it fled cities for the suburbs. Those who remained though, had a different idea of what our cities would become, and thanks to their stopping the highway builders in their tracks in the late 1950s and early 1960s, San Francisco was not crushed in this way.

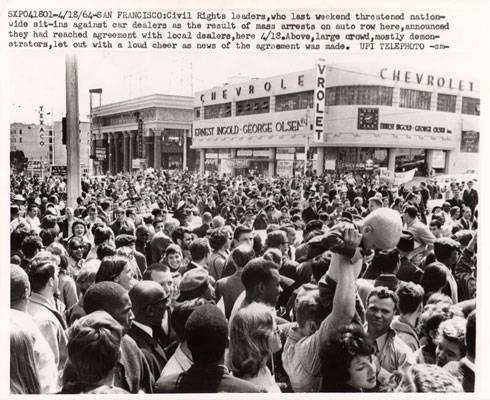

Interesting to recall that while 30,000 citizens were mobilized to stop freeway building in San Francisco (the very same elevated, pedestrian-free streets McClintock had come to endorse as an industry flack) thousands more, mostly African American and white youth, staged a vigorous civil rights campaign along auto row, demanding that blacks be given equal treatment in hiring by auto dealers, especially Don Lee’s Cadillac dealership.

Crowd cheering civil rights employment settlement with auto dealers, 1964.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Contrary to the fervent wishes of today’s motorists, streets have not always been the domain of cars. Clever marketing prior to the Depression led to radical redesign of both the physical streets and our assumptions about how public streets should be used.