Racism in the Clubs: Difference between revisions

(PC) |

(added photo) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

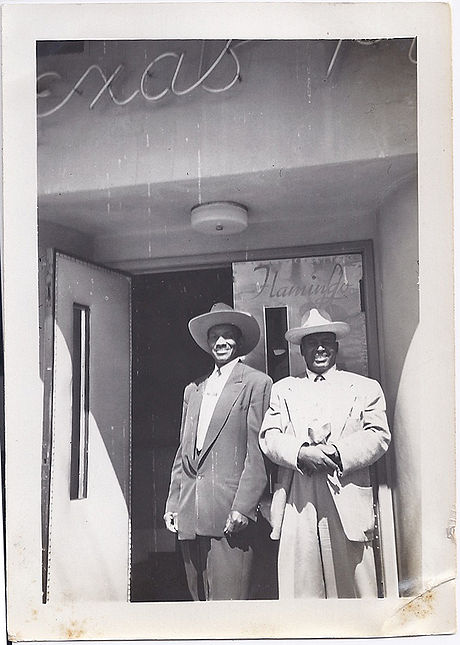

'''Wesley F. [[Wesley Johnson Senior |Johnson]], Sr. in the early 1950s, at his former [[SF's Jazz Scene |nightclub]], the Texas Playhouse, also known as Club Flamingo. It was on Fillmore between Sutter and Bush Streets.''' | '''Wesley F. [[Wesley Johnson Senior |Johnson]], Sr. in the early 1950s, at his former [[SF's Jazz Scene |nightclub]], the Texas Playhouse, also known as Club Flamingo. It was on Fillmore between Sutter and Bush Streets.''' | ||

''Photo: [http://www. | ''Photo: [http://www.sfaahcs.org/ ''African American Historical and Cultural Society], San Francisco, CA'' | ||

[[Image:TexasPlayhouseClubFlamingo.jpg|460px]] | |||

'''At the front door of the Texas Playhouse/Club Flamingo.''' | |||

''Photo: Smash'' | |||

Bassist Vernon Alley, a San Francisco native, describes, from his black perspective "the time in San Francisco when black bands couldn't play east of Van Ness Avenue, and that's true. I was a part of it. I was one of the guys who helped bring it down. [[Saunders King: S.K.'s Blues |Saunders King]] had a little group and we played down at Sutter and Powell at a place called the South Seas. There were [other] musicians' unions and the other [white] musicians' union used to fight having us play downtown. Unless it was a place like Zanzibar, Plantation, an African name, the Cotton Club or something like that." Many a black musician struggled to make a living by playing behind curtains for tourists at strip joints, out of sight so the audience could concentrate on the strippers. It was demeaning work, but it was steady. | Bassist Vernon Alley, a San Francisco native, describes, from his black perspective "the time in San Francisco when black bands couldn't play east of Van Ness Avenue, and that's true. I was a part of it. I was one of the guys who helped bring it down. [[Saunders King: S.K.'s Blues |Saunders King]] had a little group and we played down at Sutter and Powell at a place called the South Seas. There were [other] musicians' unions and the other [white] musicians' union used to fight having us play downtown. Unless it was a place like Zanzibar, Plantation, an African name, the Cotton Club or something like that." Many a black musician struggled to make a living by playing behind curtains for tourists at strip joints, out of sight so the audience could concentrate on the strippers. It was demeaning work, but it was steady. | ||

[[Image:VERNON-ALLEY-at-the-MATADOR.jpg]] | |||

'''Vernon Alley playing at the Matador club, c. 1950s.''' | |||

''Photo: courtesy Dick Boyd'' | |||

On some occasions, the white union picketed white musicians who played in black clubs, but no one I interviewed recalled the black union picketing black musicians who played in white clubs. Drummer Dick Berk has some thoughts on that period, from a Jewish perspective: "I, at the time, didn't belong to any union. And I was playing at Bop City." Independent musicians like Dick Berk were usually pressured to join the union. Sammy Simpson, tenor saxophone player and president of the black union, was a good friend of Dick. Sammy asked Dick to join the black union, even though Dick was Jewish. Feeling honored and surprised, Dick responded: 'And I said, 'Well, can I?' He says, 'I'm the president of the black union, so you can join it." And Berk did, possibly becoming the first white musician to join a black union... | On some occasions, the white union picketed white musicians who played in black clubs, but no one I interviewed recalled the black union picketing black musicians who played in white clubs. Drummer Dick Berk has some thoughts on that period, from a Jewish perspective: "I, at the time, didn't belong to any union. And I was playing at Bop City." Independent musicians like Dick Berk were usually pressured to join the union. Sammy Simpson, tenor saxophone player and president of the black union, was a good friend of Dick. Sammy asked Dick to join the black union, even though Dick was Jewish. Feeling honored and surprised, Dick responded: 'And I said, 'Well, can I?' He says, 'I'm the president of the black union, so you can join it." And Berk did, possibly becoming the first white musician to join a black union... | ||

Latest revision as of 15:22, 4 June 2020

Unfinished History

Wesley F. Johnson, Sr. in the early 1950s, at his former nightclub, the Texas Playhouse, also known as Club Flamingo. It was on Fillmore between Sutter and Bush Streets.

Photo: African American Historical and Cultural Society, San Francisco, CA

At the front door of the Texas Playhouse/Club Flamingo.

Photo: Smash

Bassist Vernon Alley, a San Francisco native, describes, from his black perspective "the time in San Francisco when black bands couldn't play east of Van Ness Avenue, and that's true. I was a part of it. I was one of the guys who helped bring it down. Saunders King had a little group and we played down at Sutter and Powell at a place called the South Seas. There were [other] musicians' unions and the other [white] musicians' union used to fight having us play downtown. Unless it was a place like Zanzibar, Plantation, an African name, the Cotton Club or something like that." Many a black musician struggled to make a living by playing behind curtains for tourists at strip joints, out of sight so the audience could concentrate on the strippers. It was demeaning work, but it was steady.

Vernon Alley playing at the Matador club, c. 1950s.

Photo: courtesy Dick Boyd

On some occasions, the white union picketed white musicians who played in black clubs, but no one I interviewed recalled the black union picketing black musicians who played in white clubs. Drummer Dick Berk has some thoughts on that period, from a Jewish perspective: "I, at the time, didn't belong to any union. And I was playing at Bop City." Independent musicians like Dick Berk were usually pressured to join the union. Sammy Simpson, tenor saxophone player and president of the black union, was a good friend of Dick. Sammy asked Dick to join the black union, even though Dick was Jewish. Feeling honored and surprised, Dick responded: 'And I said, 'Well, can I?' He says, 'I'm the president of the black union, so you can join it." And Berk did, possibly becoming the first white musician to join a black union...

The situation at Jimbo's Bop City was different from the rest of America. Former Bop City patron and long-time supporter of integration Patricia Nacey explains, "What was exciting about Jimbo's was it didn't matter. Your race or your color or your gender, even. If you wanted to go out and listen to music that's where you could go."

--Carol Chamberland