Scavengers: Difference between revisions

(PC and protected) |

(added photo) |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | ||

''by | ''by Chris Carlsson'' | ||

[[Image:italian1$brisbane-dump.jpg]] | [[Image:italian1$brisbane-dump.jpg]] | ||

'''The Brisbane Dump, in the shadow of [[San Bruno Mountain | San Bruno Mountain]], San Francisco's waste disposal for over 30 years. The stench from garbage wafting up to San Bruno Mtn. helped save it from development, since no one wanted to live with that smell!''' | '''The [[Tunnel Road Dump|Brisbane Dump]], in the shadow of [[San Bruno Mountain | San Bruno Mountain]], San Francisco's waste disposal for over 30 years. The stench from garbage wafting up to San Bruno Mtn. helped save it from development, since no one wanted to live with that smell!''' | ||

''Photos: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | ''Photos: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | ||

[[Image:Belli.jpg]] | |||

In the late 19th century and into the 20th, garbage collection ("scavenging") was controlled by Italians from the area known as Lorsica. Until 1910, when more workers were needed, they were hired from that province in Italy, rather than from among other Italians in North Beach. For the next quarter century the Lorsicani of San Francisco provided enough children to satisfy the need for new workers. | '''[[Daughter of a Sunset Scavenger|Ines Belli]]’s father and uncle, circa 1912.''' | ||

''Photo courtesy Ines Belli'' | |||

[[Image:Scavs930.gif]] | |||

'''Scavengers on the job, 1930s.''' | |||

''Photo: Private Collection'' | |||

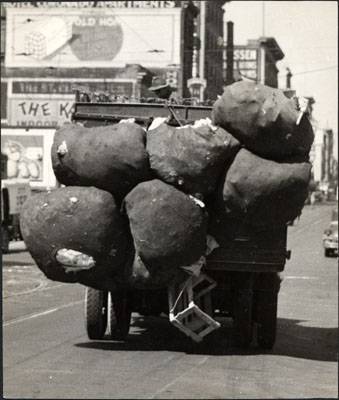

[[Image:Scavenger truck 1936 AAK-1493.jpg|right]] '''View of burlap bundles of recyclables hanging from a 1936 Scavenger truck.''' | |||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | |||

The story of San Francisco’s garbagemen, or scavengers, or as some like to say “sanitation engineers,” is a surprising and fascinating story. In the late 19th century and into the 20th, garbage collection ("scavenging") was controlled by Italians from the area known as Lorsica, near the city of Genoa. Until 1910, when more workers were needed, they were hired from that province in Italy, rather than from among other Italians in North Beach. (Also, newly arrived Italian immigrants had a hard time finding other kinds of work.) For the next quarter century the Lorsicani of San Francisco provided enough children to satisfy the need for new workers. They would pass through these San Francisco neighborhoods with horse-drawn wagons gathering refuse from the households along the way. Before WWII and the packaging and plastics revolution that followed, nearly everything had a potential use or was made of organic materials and could be decomposed. | |||

One of the largest of the companies was the Scavengers Protective Association, which was founded by Andrea Sbaboro, one of the prominenti of the city. Another large company was started before WWI by Emilio Rattaro as the Sunset Scavenger Company with about 100 workers (there were about 400 garbage men in the city). After city legislation in 1920 specified districts and rates, Sunset was formally incorporated in 1921. | One of the largest of the companies was the Scavengers Protective Association, which was founded by Andrea Sbaboro, one of the prominenti of the city. Another large company was started before WWI by Emilio Rattaro as the Sunset Scavenger Company with about 100 workers (there were about 400 garbage men in the city). After city legislation in 1920 specified districts and rates, Sunset was formally incorporated in 1921. | ||

In 1932 there were a total of 97 districts served by 36 companies. Yet the Depression took a toll, and by 1935 there were only three districts. In 1939 the Sunset Scavengers | In 1932 there were a total of 97 districts served by 36 companies. Yet the Depression took a toll, and by 1935 there were only three districts. In 1939 the [[San Francisco's Trash|Sunset Scavengers]] bought Mission Scavengers, leaving only two districts: Sunset and the Scavengers Protective Association. | ||

Leonard Stefanelli, president of Sunset Scavenger after a sudden revolt of shareholders against the long-time management, captured the schizophrenic quality of the scavenger companies decades later: | |||

<blockquote>“I have referred to Sunset Scavenger as a capitalistic, communistic society. In theory, it was capitalist; in reality, it was also a communistic organization. The common goal was for everybody to own an equal share of equity as well as equal income and benefits, but a single person made the decisions. The final analysis was simple: it was a communistic society. .. The corporation bylaws governed the company. One key and unique component of the bylaws was that everybody was paid “absolutely alike, regardless of office position or responsibility.” Whether you were a truck boss, driver, mechanic, officer, or light-duty worker, you made the same amount of money as everyone else.” *</blockquote> | |||

Sunset Scavenger had its corporate offices on Hampshire near 19th Street, but most of the Boss Scavengers lived further west, many on today’s Oakwood Street when it was a dead-end alley from 18th near Dolores. Boarding houses and stables crowded the cul-de-sac and every night the scavengers’ horses and carts would fill what they commonly referred to as “Dago Alley.” Stefanelli says his three uncles had places on the alley, along with many Sunset “Boss Scavengers” with names like Campi, Fontana, Chiosso, Borghello, Onarato, Moscone, Leonardini, Guaraglia, Scolari, Salvi, and Musante. | |||

[[Image:Oakwood near 19th Jun 12, 1915 wnp36.00828.jpg|800px]] | |||

'''Oakwood Street, a.k.a. "Dago Alley" looking south towards 19th Street, June 12, 1915.''' | |||

''Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp36.00828'' | |||

The two companies founded a third entity in 1935, the Sanitary Fill Company, which ran the dump on Tunnel Road, assuming responsibility from Southern Pacific railroad after 1952 for slowly filling in Brisbane Lagoon over the course of a half century. The techniques pioneered by Sanitary Fill Company—covering garbage with layers of fresh soil cut from the flanks of [[Bayview Hill|Bayview Hill]]—long before any regulatory laws were passed, helped cut down on blowing garbage and the raw stench long associated with dumps. (Ironically, it was the stench of the garbage here blowing south across the flanks of [[San Bruno Mountain|San Bruno Mountain]] that probably saved the mountain from rampant development in the mid-twentieth century.) | |||

[[Image:Bay Shore R. R. View looking North from Sierra Point. March 31, 1905 11-southern-pacific-company viewfromsierrapt-3-31-1905.jpg|720px]] | |||

'''Bay Shore Railroad looking north from Sierra Point, March 31, 1905.''' | |||

''Photo: Private Collection'' | |||

[[Image:March11 1926 Bayshore Marsh - railroad dpwbook36 dpw10210 wnp36.03363.jpg|792px]] | |||

'''Twenty years later, this train coursing the shoreline around [[San Bruno Mountain|San Bruno Mountain]] at tip of Sierra Point (1926) is no longer on a trestle over water but part of the expanding landfill beneath San Bruno Mountain. Brisbane Lagoon hasn't yet been filled as a dump, and there isn't yet any Highway 101.''' | |||

''Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp36.03363; DPW Book 36, DPW 10210'' | |||

When the original McAteer-Petris Act passed in 1965 to create the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, dumping garbage in the bay would soon be halted. But Sunset and the Sanitary Fill Company, recognizing that their existing dump was nearly full, had already identified some tidelands off the eastern edge of San Bruno Mountain at Sierra Point to use as their next sanitary landfill. Millions of dollars was spent to prepare the site and when Brisbane’s City Council tried to reverse their original support for the landfill, Sunset dramatically and publicly went ahead and moved their operations to the new site. Stefanelli was by then the President of Sunset Scavenger and, egged on by his attorney, was driving the truck that blew through a police barricade: | |||

<blockquote>“Time was running out—by now it was July 1966. The current waste site would fill to capacity in three short months… With my approval, along with the people of Sanitary Fill Company and the Easley & Brassy Corporation, Scavenger’s Protective Association agreed to proceed. The plan was confidential and would be implemented through tactics similar to a well-planned military action. On a Friday night in late November of 1966, we would terminate the current operations on the west side of the freeway in the City of Brisbane and begin dumping garbage at Sierra Point.”</blockquote> | |||

Repeated efforts by Brisbane citizens to block the bay dumping eventually failed. [[Sierra Point: From Dump to Office Park|Sierra Point]] today is an office park east of Highway 101 at the southeast corner of San Bruno Mountain. | |||

The next location for San Francisco’s garbage dump became the wetlands in Mountain View where a future park was promised (and eventually became home too to the Shoreline Amphitheatre) along with substantial fees from the garbage companies to the city coffers. Once that landfill was exhausted, San Francisco began sending its garbage to the Altamont Pass dump in eastern Alameda County, which it is still using at present. | |||

[[Image:Brisbane-lagoon-and-fwy-1955-AAC-5259.jpg]] | |||

'''Aerial view southward along the Highway 101 construction corridor in 1955, Brisbane Lagoon still being filled by [[San Francisco's Trash|San Francisco's garbage]].''' | |||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | |||

[[Image:View-north-across-remains-of-brisbane-lagoon-w-bayview-hill-and--fwy 20200126 155258.jpg]] | |||

'''View north in 2020 across remains of Brisbane Lagoon, Bayview Hill in distance, Highway 101 on causeway between lagoon and bay.''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | |||

By 1966, Scavenger’s Protective Association had changed its name to Golden Gate Disposal, and continued to see its business grow rapidly since their territory was largely the northeastern part of San Francisco encompassing the Financial District which was was increasingly vertical. In 1972 Sunset Scavenger merged its operations with Los Altos South Valley, Stockton Scavenger, Sanitary Fill Company, Joseph Petigera Company (our independent salvage/recycling entity), and others, and took the name Envirocal. | |||

In the early 1970s, Golden Gate Disposal took its growing profits to buy out the original share structure that the companies had maintained since their founding a half century earlier and replace it with an Employee Stock Ownership Plan. Sunset Scavenger’s profits were shrinking due to being dependent on residential areas, in contrast to Golden Gate Disposal’s growing downtown business. In both companies, wages that had been identical for decades now began to vary depending on more typical considerations. Seeking to expand into the lucrative trash business throughout Northern California, Golden Gate Disposal changed its name to Norcal Solid Waste Systems in 1983. In 1986, Norcal was sold back to the original Employee Stock Ownership Plan, and a year later it absorbed the former Envirocal/Sunset Scavenger, becoming one company. | |||

Soon after, Norcal Waste, certain that their clients would never recycle, and institutionally opposed to the “hippie” approach to solid waste, sought to build a massive incinerator just south of city limits in Brisbane. Supervisors of both San Francisco and San Mateo approved the plan, as did the city council of Brisbane, but Brisbane citizens revolted. A popular initiative was put on the ballot, and the NIMBYs of Brisbane [[San Francisco's Trash|defeated the planned incinerator]] (which would have spewed toxic exhaust over their town), foiling the plans of Norcal and PG&E (who would have generated electricity with the burned trash). Combined with the California statewide mandate to reduce waste due to overflowing landfills, the renamed Recology had to establish curbside recycling in San Francisco, now taken for granted by City residents. | |||

* Quotes from ''Garbage: The Saga of a Boss Scavenger in San Francisco'' by Leonard Dominic Stefanelli, University of Nevada Press: 2018 | |||

[[Image:italian1$guanaglias-father-and-son.jpg]] | [[Image:italian1$guanaglias-father-and-son.jpg]] | ||

| Line 25: | Line 91: | ||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | ||

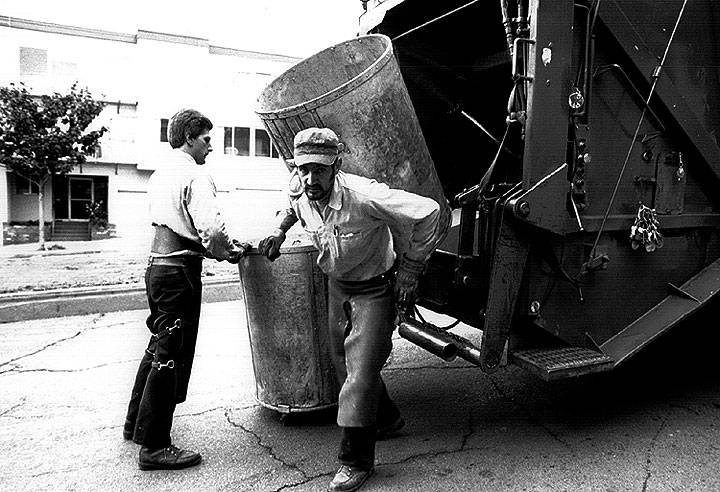

[[Image: | [[Image:GARBMEN2.jpg]] | ||

'''San Francisco Scavengers at work.''' | '''San Francisco Scavengers at work in the 1990s, before the introduction of the [[San Francisco's Trash|curbside recycling]] and plastic bin system.''' | ||

''Photo: Rick Gerharter'' | ''Photo: Rick Gerharter'' | ||

| Line 34: | Line 100: | ||

[[Bank of Italy| Prev. Document]] [[Italians and Sports| Next Document]] | [[Bank of Italy| Prev. Document]] [[Italians and Sports| Next Document]] | ||

[[category:Italian]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:Labor]] [[category:Ecology]] | [[category:Italian]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:Labor]] [[category:Ecology]] [[category:Waste]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:North Beach]] [[category:Visitacion Valley]] [[category:2020s]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:57, 16 June 2020

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

The Brisbane Dump, in the shadow of San Bruno Mountain, San Francisco's waste disposal for over 30 years. The stench from garbage wafting up to San Bruno Mtn. helped save it from development, since no one wanted to live with that smell!

Photos: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Ines Belli’s father and uncle, circa 1912.

Photo courtesy Ines Belli

Scavengers on the job, 1930s.

Photo: Private Collection

View of burlap bundles of recyclables hanging from a 1936 Scavenger truck.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The story of San Francisco’s garbagemen, or scavengers, or as some like to say “sanitation engineers,” is a surprising and fascinating story. In the late 19th century and into the 20th, garbage collection ("scavenging") was controlled by Italians from the area known as Lorsica, near the city of Genoa. Until 1910, when more workers were needed, they were hired from that province in Italy, rather than from among other Italians in North Beach. (Also, newly arrived Italian immigrants had a hard time finding other kinds of work.) For the next quarter century the Lorsicani of San Francisco provided enough children to satisfy the need for new workers. They would pass through these San Francisco neighborhoods with horse-drawn wagons gathering refuse from the households along the way. Before WWII and the packaging and plastics revolution that followed, nearly everything had a potential use or was made of organic materials and could be decomposed.

One of the largest of the companies was the Scavengers Protective Association, which was founded by Andrea Sbaboro, one of the prominenti of the city. Another large company was started before WWI by Emilio Rattaro as the Sunset Scavenger Company with about 100 workers (there were about 400 garbage men in the city). After city legislation in 1920 specified districts and rates, Sunset was formally incorporated in 1921.

In 1932 there were a total of 97 districts served by 36 companies. Yet the Depression took a toll, and by 1935 there were only three districts. In 1939 the Sunset Scavengers bought Mission Scavengers, leaving only two districts: Sunset and the Scavengers Protective Association.

Leonard Stefanelli, president of Sunset Scavenger after a sudden revolt of shareholders against the long-time management, captured the schizophrenic quality of the scavenger companies decades later:

“I have referred to Sunset Scavenger as a capitalistic, communistic society. In theory, it was capitalist; in reality, it was also a communistic organization. The common goal was for everybody to own an equal share of equity as well as equal income and benefits, but a single person made the decisions. The final analysis was simple: it was a communistic society. .. The corporation bylaws governed the company. One key and unique component of the bylaws was that everybody was paid “absolutely alike, regardless of office position or responsibility.” Whether you were a truck boss, driver, mechanic, officer, or light-duty worker, you made the same amount of money as everyone else.” *

Sunset Scavenger had its corporate offices on Hampshire near 19th Street, but most of the Boss Scavengers lived further west, many on today’s Oakwood Street when it was a dead-end alley from 18th near Dolores. Boarding houses and stables crowded the cul-de-sac and every night the scavengers’ horses and carts would fill what they commonly referred to as “Dago Alley.” Stefanelli says his three uncles had places on the alley, along with many Sunset “Boss Scavengers” with names like Campi, Fontana, Chiosso, Borghello, Onarato, Moscone, Leonardini, Guaraglia, Scolari, Salvi, and Musante.

Oakwood Street, a.k.a. "Dago Alley" looking south towards 19th Street, June 12, 1915.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp36.00828

The two companies founded a third entity in 1935, the Sanitary Fill Company, which ran the dump on Tunnel Road, assuming responsibility from Southern Pacific railroad after 1952 for slowly filling in Brisbane Lagoon over the course of a half century. The techniques pioneered by Sanitary Fill Company—covering garbage with layers of fresh soil cut from the flanks of Bayview Hill—long before any regulatory laws were passed, helped cut down on blowing garbage and the raw stench long associated with dumps. (Ironically, it was the stench of the garbage here blowing south across the flanks of San Bruno Mountain that probably saved the mountain from rampant development in the mid-twentieth century.)

Bay Shore Railroad looking north from Sierra Point, March 31, 1905.

Photo: Private Collection

Twenty years later, this train coursing the shoreline around San Bruno Mountain at tip of Sierra Point (1926) is no longer on a trestle over water but part of the expanding landfill beneath San Bruno Mountain. Brisbane Lagoon hasn't yet been filled as a dump, and there isn't yet any Highway 101.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp36.03363; DPW Book 36, DPW 10210

When the original McAteer-Petris Act passed in 1965 to create the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, dumping garbage in the bay would soon be halted. But Sunset and the Sanitary Fill Company, recognizing that their existing dump was nearly full, had already identified some tidelands off the eastern edge of San Bruno Mountain at Sierra Point to use as their next sanitary landfill. Millions of dollars was spent to prepare the site and when Brisbane’s City Council tried to reverse their original support for the landfill, Sunset dramatically and publicly went ahead and moved their operations to the new site. Stefanelli was by then the President of Sunset Scavenger and, egged on by his attorney, was driving the truck that blew through a police barricade:

“Time was running out—by now it was July 1966. The current waste site would fill to capacity in three short months… With my approval, along with the people of Sanitary Fill Company and the Easley & Brassy Corporation, Scavenger’s Protective Association agreed to proceed. The plan was confidential and would be implemented through tactics similar to a well-planned military action. On a Friday night in late November of 1966, we would terminate the current operations on the west side of the freeway in the City of Brisbane and begin dumping garbage at Sierra Point.”

Repeated efforts by Brisbane citizens to block the bay dumping eventually failed. Sierra Point today is an office park east of Highway 101 at the southeast corner of San Bruno Mountain.

The next location for San Francisco’s garbage dump became the wetlands in Mountain View where a future park was promised (and eventually became home too to the Shoreline Amphitheatre) along with substantial fees from the garbage companies to the city coffers. Once that landfill was exhausted, San Francisco began sending its garbage to the Altamont Pass dump in eastern Alameda County, which it is still using at present.

Aerial view southward along the Highway 101 construction corridor in 1955, Brisbane Lagoon still being filled by San Francisco's garbage.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

View north in 2020 across remains of Brisbane Lagoon, Bayview Hill in distance, Highway 101 on causeway between lagoon and bay.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

By 1966, Scavenger’s Protective Association had changed its name to Golden Gate Disposal, and continued to see its business grow rapidly since their territory was largely the northeastern part of San Francisco encompassing the Financial District which was was increasingly vertical. In 1972 Sunset Scavenger merged its operations with Los Altos South Valley, Stockton Scavenger, Sanitary Fill Company, Joseph Petigera Company (our independent salvage/recycling entity), and others, and took the name Envirocal.

In the early 1970s, Golden Gate Disposal took its growing profits to buy out the original share structure that the companies had maintained since their founding a half century earlier and replace it with an Employee Stock Ownership Plan. Sunset Scavenger’s profits were shrinking due to being dependent on residential areas, in contrast to Golden Gate Disposal’s growing downtown business. In both companies, wages that had been identical for decades now began to vary depending on more typical considerations. Seeking to expand into the lucrative trash business throughout Northern California, Golden Gate Disposal changed its name to Norcal Solid Waste Systems in 1983. In 1986, Norcal was sold back to the original Employee Stock Ownership Plan, and a year later it absorbed the former Envirocal/Sunset Scavenger, becoming one company.

Soon after, Norcal Waste, certain that their clients would never recycle, and institutionally opposed to the “hippie” approach to solid waste, sought to build a massive incinerator just south of city limits in Brisbane. Supervisors of both San Francisco and San Mateo approved the plan, as did the city council of Brisbane, but Brisbane citizens revolted. A popular initiative was put on the ballot, and the NIMBYs of Brisbane defeated the planned incinerator (which would have spewed toxic exhaust over their town), foiling the plans of Norcal and PG&E (who would have generated electricity with the burned trash). Combined with the California statewide mandate to reduce waste due to overflowing landfills, the renamed Recology had to establish curbside recycling in San Francisco, now taken for granted by City residents.

- Quotes from Garbage: The Saga of a Boss Scavenger in San Francisco by Leonard Dominic Stefanelli, University of Nevada Press: 2018

1953: Charles & John Guanaglia, father and son. Charles worked the same route for 28 years, now his son is taking over.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

San Francisco Scavengers at work in the 1990s, before the introduction of the curbside recycling and plastic bin system.

Photo: Rick Gerharter