The Castro: The Rise of a Gay Community: Difference between revisions

(moved photos and added DPN cover image) |

No edit summary |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

''Photos: Crawford Barton, Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California'' | ''Photos: Crawford Barton, Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California'' | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''Many across the United States consider San Francisco to be a “Gay Mecca” due to its large gay community located primarily in the Castro District as well as the city’s relatively liberal attitude towards sex. Until the 1960’s, though, the Castro was largely a white working class Irish neighborhood known as “Eureka Valley.” A shift came during World War II, when many soldiers came to San Francisco and formed gay relationships. These soldiers then stayed in the city after being discharged for homosexuality. In the 1950s, Beat Culture erupted in San Francisco and notoriously rebelled against middle class values, thus aligning itself with homosexuality and helped bring gay culture to mainstream attention. In the mid to late 1950s, groups such as the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society were born, as well as the Tavern Guild, which was the first openly gay business association. By 1969, there were 50 gay organizations in San Francisco, and by 1973 there were 800. Unfortunately, the anti-gay feelings of the greater United States reached San Francisco in the late 70s, which were followed by the assassination of Mayor Moscone and Harvey Milk and the White Night Riot as well as the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. All of these events have led to a network of self-help organizations as well as a vibrant and strong gay community in the Castro and San Francisco.''' | |||

|} | |||

Homosexuals across America consider San Francisco a "Gay Mecca" thanks to the rise of the distinctive gay community, primarily in the [[18th and Castro 1914-5 |Castro District]], centered at the intersection of Castro and 18th Streets, a block from upper Market Street. Some estimate that there are as many as 100,000 gay men and lesbians in San Francisco, out of a total population of approximately 750,000. | Homosexuals across America consider San Francisco a "Gay Mecca" thanks to the rise of the distinctive gay community, primarily in the [[18th and Castro 1914-5 |Castro District]], centered at the intersection of Castro and 18th Streets, a block from upper Market Street. Some estimate that there are as many as 100,000 gay men and lesbians in San Francisco, out of a total population of approximately 750,000. | ||

| Line 28: | Line 31: | ||

When it finally closed in 1963, The Black Cat had broken the barriers that prevented overtly gay bars from existing freely. A 1951 California Supreme Court decision banned the closing down of a bar simply because homosexuals were the usual customers. Manuel Castells convincingly argues in ''The Grassroots and the City'' that The Black Cat had also established an important cultural precedent for the gay community: fun and humor. As the community developed, feasts, celebrations, street parties, public and private bars, and bathhouses and sex clubs, became the important forms of cultural expression and sociability, which in turn strongly influenced other communities in San Francisco and beyond. The element of immediate pleasure and fun that gays strove to establish in their daily lives found an emphatic echo and expansion in the hippie movement of the 1960s. The anti-war and counter-culture movements in general provided a relatively pro-pleasure climate for gays. | When it finally closed in 1963, The Black Cat had broken the barriers that prevented overtly gay bars from existing freely. A 1951 California Supreme Court decision banned the closing down of a bar simply because homosexuals were the usual customers. Manuel Castells convincingly argues in ''The Grassroots and the City'' that The Black Cat had also established an important cultural precedent for the gay community: fun and humor. As the community developed, feasts, celebrations, street parties, public and private bars, and bathhouses and sex clubs, became the important forms of cultural expression and sociability, which in turn strongly influenced other communities in San Francisco and beyond. The element of immediate pleasure and fun that gays strove to establish in their daily lives found an emphatic echo and expansion in the hippie movement of the 1960s. The anti-war and counter-culture movements in general provided a relatively pro-pleasure climate for gays. | ||

In 1969 there were 50 gay organizations. The famous Stonewall Riot in New York City in June 1969, led to an explosion of gay consciousness and self-organization. By 1973 there were over 800 organizations. Gay bars grew from 58 in 1969 to 234 in 1980. By organizing socially, culturally, and politically, the gay community came into its own in the 1970s. Its best known hero was Harvey Milk, a former camera store owner who used aggressive door-to-door (and bar-to-bar, corner-to-corner) populist organizing techniques to get elected to the city's Board of Supervisors. In fact, his election coincided with the establishment of a new coalition of progressive community organizations that together established a district election system in place of the downtown dominated at-large system, a victory which followed by two years the election of liberal state Senator George Moscone as mayor in 1975. | In 1969 there were 50 gay organizations. The famous Stonewall Riot in New York City in June 1969, led to an explosion of gay consciousness and self-organization. By 1973 there were over 800 organizations. Gay bars grew from 58 in 1969 to 234 in 1980. By organizing socially, culturally, and politically, the gay community came into its own in the 1970s. | ||

[[Image:Gay Freedom Day 1976 Gaar wnp72.085.jpg|800px]] | |||

'''[[Gay Freedom Day 1974|Gay Freedom Day in 1974]], when the gay community was equally focused on the Polk Gulch area, as seen in this photo.''' | |||

''Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp72.085; © Greg Gaar Photography'' | |||

Its best known hero was Harvey Milk, a former camera store owner who used aggressive door-to-door (and bar-to-bar, corner-to-corner) populist organizing techniques to get elected to the city's Board of Supervisors. In fact, his election coincided with the establishment of a new coalition of progressive community organizations that together established a district election system in place of the downtown dominated at-large system, a victory which followed by two years the election of liberal state Senator George Moscone as mayor in 1975. | |||

[[Image:gay1$dykes-on-bikes.jpg]] | [[Image:gay1$dykes-on-bikes.jpg]] | ||

| Line 48: | Line 59: | ||

[[The Bubble Bursts | Prev. Document]] [[Sisters--Against Guilt | Next Document]] | [[The Bubble Bursts | Prev. Document]] [[Sisters--Against Guilt | Next Document]] | ||

[[category: | [[category:LGBTQI]] [[category:Castro]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:1990s]] [[category:Irish]] [[category:Polk Gulch]] | ||

Latest revision as of 13:57, 16 July 2020

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson, 1995

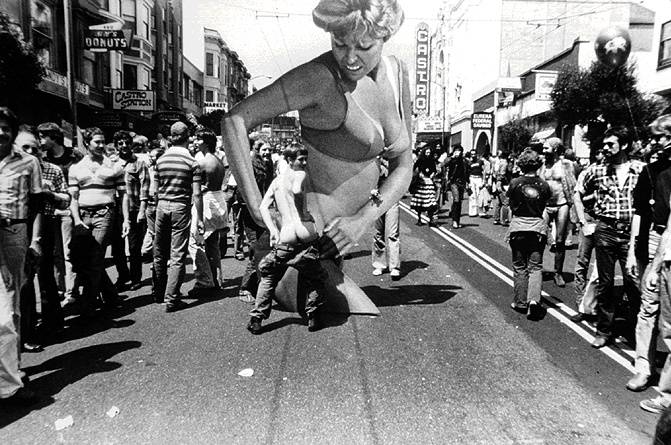

Castro Street Fair, 1978

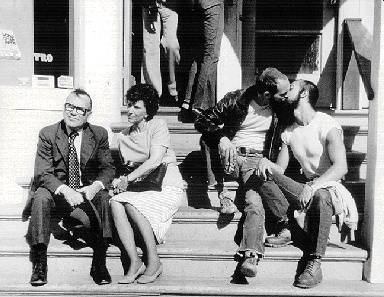

Castro Street Scene 1970s

Photos: Crawford Barton, Gay and Lesbian Historical Society of Northern California

| Many across the United States consider San Francisco to be a “Gay Mecca” due to its large gay community located primarily in the Castro District as well as the city’s relatively liberal attitude towards sex. Until the 1960’s, though, the Castro was largely a white working class Irish neighborhood known as “Eureka Valley.” A shift came during World War II, when many soldiers came to San Francisco and formed gay relationships. These soldiers then stayed in the city after being discharged for homosexuality. In the 1950s, Beat Culture erupted in San Francisco and notoriously rebelled against middle class values, thus aligning itself with homosexuality and helped bring gay culture to mainstream attention. In the mid to late 1950s, groups such as the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society were born, as well as the Tavern Guild, which was the first openly gay business association. By 1969, there were 50 gay organizations in San Francisco, and by 1973 there were 800. Unfortunately, the anti-gay feelings of the greater United States reached San Francisco in the late 70s, which were followed by the assassination of Mayor Moscone and Harvey Milk and the White Night Riot as well as the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. All of these events have led to a network of self-help organizations as well as a vibrant and strong gay community in the Castro and San Francisco. |

Homosexuals across America consider San Francisco a "Gay Mecca" thanks to the rise of the distinctive gay community, primarily in the Castro District, centered at the intersection of Castro and 18th Streets, a block from upper Market Street. Some estimate that there are as many as 100,000 gay men and lesbians in San Francisco, out of a total population of approximately 750,000.

The Castro wasn't always a gay neighborhood. Until the early 1960s it was primarily white working-class, predominantly of Irish descent, and better known as "Eureka Valley." But as the post-WWII trend of white flight to the suburbs drew more and more older San Franciscan families out, new groups moved in behind them. In most U.S. cities, such in-migration was typically that of ethnic minorities, mostly blacks, Latinos and Asians. This was also true in San Francisco, but thanks to several coincidences, SF also became home to thousands of gays, and the Castro is the district in which they decided to spend their money, put down roots and make a home.

The city was always known for its relatively libertine attitudes towards sex and pleasure. The Barbary Coast and the waterfront brought together travelers, sailors, transients and others in casual encounters far from the prevailing rules "back home." Hundreds of houses of prostitution flourished from the Gold Rush through the early 20th century, followed decades later by the rise of topless bars and strip joints, and the pornographic film industry (The Mitchell Brothers being the best known), all contributing to a sexual openness that gave San Francisco a reputation directly challenging the sexual repressiveness that prevailed in the rest of the country. This in turn made San Francisco an attractive destination for those deemed "outlaws" by the dominant morals of society.

World War II provided a big impetus for the development of San Francisco's gay community. One and a half million soldiers, 10%+ of which were homosexual, were able to find each other more easily in the marginal districts of San Francisco. Thousands were discharged by the military for homosexuality and were released in San Francisco. Rather than returning to the hinterlands in which they would be stigmatized, many stayed on and after the war they were joined by thousands more who had discovered new identities in the crucible of war. The Black Cat Cafe on Montgomery Street became home to a gay drag revue starring Jose Sarria. Sarria was born in San Francisco and performed each Sunday afternoon for fifteen years to full houses of 250 or more, using his role as Madam Butterfly to sermonize about homosexual rights and leading a sing-along of "God Save the Nelly Queens."

During the 1950s San Francisco also spawned the Beat Culture, which shared spaces and attitudes with the incipient gay culture. Allen Ginsberg, himself gay, wrote Howl and fought obscenity charges in 1957. The beats expressed a basic rejection of American middle class values, especially the family and suburbanism, which coincided closely with early gay attitudes. Of course, it can be argued that a good deal of gay culture tries to emulate middle class America and its values, helping homosexuality to become more mainstream and less stigmatized. Bars and nightclubs in North Beach and the Tenderloin became important sources of cross-pollination and expansion.

In 1962 police and alcohol control board harassment led to the establishment of the Tavern Guild, consisting of the owners of primarily gay and bohemian establishments. The Guild became the first overtly gay business association and provided one of the first organizational backbones of the gay community. Earlier, in 1955, the Mattachine Society (one of the first ever gay organizations) had moved its headquarters from Los Angeles to San Francisco and eventually spawned The Advocate, the nation's first gay magazine. The Daughters of Bilitis, the first openly lesbian organization, was founded in San Francisco, also in 1955. Mayor George Christopher, a relatively conservative Republican, was criticized by an even more conservative challenger, Russell Wolden, in his 1959 re-election campaign for allowing the city to become "the national headquarters of organized homosexuals in America," but the establishment and local press criticized Wolden for harming the image of San Francisco and Christopher was re-elected.

When it finally closed in 1963, The Black Cat had broken the barriers that prevented overtly gay bars from existing freely. A 1951 California Supreme Court decision banned the closing down of a bar simply because homosexuals were the usual customers. Manuel Castells convincingly argues in The Grassroots and the City that The Black Cat had also established an important cultural precedent for the gay community: fun and humor. As the community developed, feasts, celebrations, street parties, public and private bars, and bathhouses and sex clubs, became the important forms of cultural expression and sociability, which in turn strongly influenced other communities in San Francisco and beyond. The element of immediate pleasure and fun that gays strove to establish in their daily lives found an emphatic echo and expansion in the hippie movement of the 1960s. The anti-war and counter-culture movements in general provided a relatively pro-pleasure climate for gays.

In 1969 there were 50 gay organizations. The famous Stonewall Riot in New York City in June 1969, led to an explosion of gay consciousness and self-organization. By 1973 there were over 800 organizations. Gay bars grew from 58 in 1969 to 234 in 1980. By organizing socially, culturally, and politically, the gay community came into its own in the 1970s.

Gay Freedom Day in 1974, when the gay community was equally focused on the Polk Gulch area, as seen in this photo.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp72.085; © Greg Gaar Photography

Its best known hero was Harvey Milk, a former camera store owner who used aggressive door-to-door (and bar-to-bar, corner-to-corner) populist organizing techniques to get elected to the city's Board of Supervisors. In fact, his election coincided with the establishment of a new coalition of progressive community organizations that together established a district election system in place of the downtown dominated at-large system, a victory which followed by two years the election of liberal state Senator George Moscone as mayor in 1975.

Dykes on Bikes, a distinctive feature of SF Gay Pride parades.

Photo: David Green

The upsurge of anti-gay, homophobic feelings in the United States came to San Francisco, too. In 1978, an ultra-conservative state senator put on the statewide ballot the Briggs Initiative, intended to ban gays from teaching in the public schools. With the energetic participation of Milk and thousands of newly self-empowered gay activists, Briggs was defeated by a sound majority. Not long after the election, a disgruntled conservative ex-cop who had recently resigned his seat on San Francisco's Board of Supervisors, Dan White, entered City Hall through a side door (one which lacked a metal detector) and murdered Mayor Moscone and Supervisor Milk. When Dan White was given a virtual slap on the wrist for this cold-blooded murder in a jury trial (the verdict of voluntary manslaughter was handed down on May 21, 1979) one of the biggest riots in SF history exploded in the Civic Center Plaza, known as the White Night Riot.

As Feinstein proceeded with the downtown expansion plans and put community initiatives on hold, gays fragmented along various lines. Under Reagan many conservative assumptions were adapted to, and gay politics became more an interest group and less a progressive agenda. Perhaps the class divisions among gays eroded the earlier Milk/Harry Britt tradition of gay leftism. The AIDS crisis struck in the early 1980s, with thousands of San Francisco's most creative, intelligent and exciting people perishing in the epidemic. Gay politics became very focused on getting resources dedicated to the AIDS situation, or more practically, on the creation of an astounding network of self-help organizations. Two outspoken lesbians were elected to the Board of Supervisors in 1992, one of whom, Roberta Achtenberg, went on to be appointed a high-end official in the Clinton Administration's Housing Department. Carole Migden, the second, led a budget committee to cut pay and benefits to city workers in her effort to be the responsible centrist lesbian, palatable to downtown.

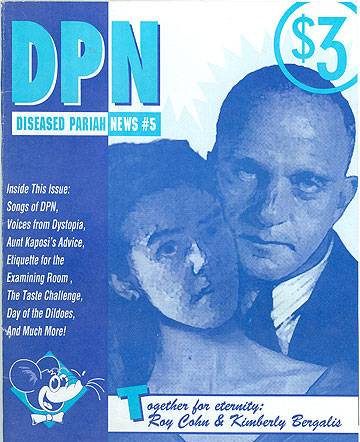

The above-ground gay press in San Francisco supports an impressive three fat weeklies, Bay Times, Bay Area Reporter (BAR), and in the 1970's The Sentinel. The first is a more meaty rag, featuring very long pieces on many issues facing the gay community. BAR and Sentinel both carry a lot more advertising. Meanwhile, the underground gay press is exploding with dozens of wild 'zines, from the hardcore to the no-core to homocore. Diseased Pariah News, A Taste of Latex, On Our Backs, Raw Vulva, there are blistering, often hilarious, often erotic writings from the daily lives of fags and dykes, bi- and transsexuals, and transgender individuals.