South of Market Boys: Difference between revisions

(reorganized photos, minor proofreading and formatting) |

m (Protected "South of Market Boys" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite))) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 11:07, 8 October 2020

Historical Essay

by Adam Jancsek

South of Market Ball at the Civic Auditorium.

Photo: South of Market Journal, January 1926

For an organization that is so quintessentially San Franciscan, there is not much information to be found about the South of Market Boys, an organization that helped shape the cultural landscape of Depression-era San Francisco. There are a wide range of anecdotes found online:

“A local street gang”

“A fraternal drinking club”

“A club of San Francisco old timers”

and the most ridiculous: “The tech bro drinking club of the day.”

These descriptions do not capture the full essence of the group. So who really were the South of Market Boys?

To put it simply, the South of Market Boys were a group of men who grew up in the South of Market district prior to 1906. To understand why such a group was created, one must understand the area from which they came. Before the 1906 earthquake, South of Market was a crowded, working-class neighborhood, a sort of “Lower East Side” in San Francisco. The Irish were the most numerous in the area, and though many other ethnic groups lived within its boundaries, South of Market became associated with a blue collar, Irish identity. Many saloons, sweatshops, factories, and other businesses shared the space with dense housing that lined the streets and numerous alleys to create a dense, busy neighborhood. Many outside South of Market viewed it as a slum, and indeed, it was a primary target of “urban renewal” starting in the mid 20th century. As far back as the late 19th century, its residents had a tough reputation- seen as ruffians by those outside the neighborhood.

Destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire, South of Market was not rebuilt in the same manner. What once were tightly packed houses and flats became garages, industrial buildings, some hotels, or vacant lots. Traumatized by the destruction of the fire, residents left the inner city. The most popular destination was the Mission, which carried on South of Market’s legacy as a blue-collar Irish neighborhood through the mid 20th century. Many others settled in the formerly rural but rapidly urbanizing areas in the southeast corner of the City. Still others migrated to the Peninsula, the East Bay, or farther afield. The 19th century South of Market would never exist again.

All this set the stage for the emergence of the South of Market Boys (SOM Boys). Many erroneous dates float around about their founding, but Peter R. Maloney, a founder himself, gave the date of November 11, 1924, in his own history of the group.

South of Market's reputation did not stop its residents from becoming the next generation of civic leaders.

San Francisco Examiner, April 11, 1925

Maloney co-founded the SOM Boys along with a few others, notably his brother, state senator Tom Maloney. His idea was simple: to bring “together all the men who had lived south of Market Street before the fire of 1906” (which they defined as south of Market Street and east of 12th Street.) He wrote that 127 men attended the initial meeting at the New Call Building, and only ten years later, the organization boasted over 3,500 men.

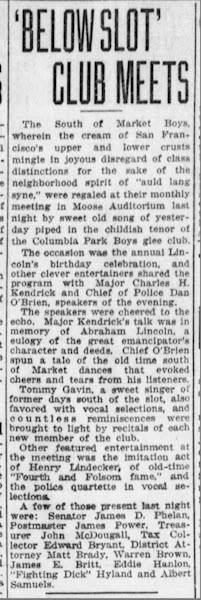

But what did they actually do? The former San Francisco Chronicle columnist Robert O’Brien wrote that they were “dedicated to the perpetuation of the spirit of the old South of Market”, which nicely encapsulates them. They threw many picnics, balls, and other events, bringing together the old boys from the neighborhood. Their annual St. Patrick’s Day celebration was known as the largest in the City, and the Mother’s Day Luncheon was always well attended. Their main annual events were the Anniversary Balls, held on April 18 of every year.

But the South of Market Boys were more than just a drinking club. They engaged in a wide range of charitable activities throughout San Francisco. A main concern was the St. Patrick’s shelter, located in the old neighborhood at 239 Minna Street. Monthly reports on the shelter were given in their Journal, and the SOM Boys were some of its main financiers.

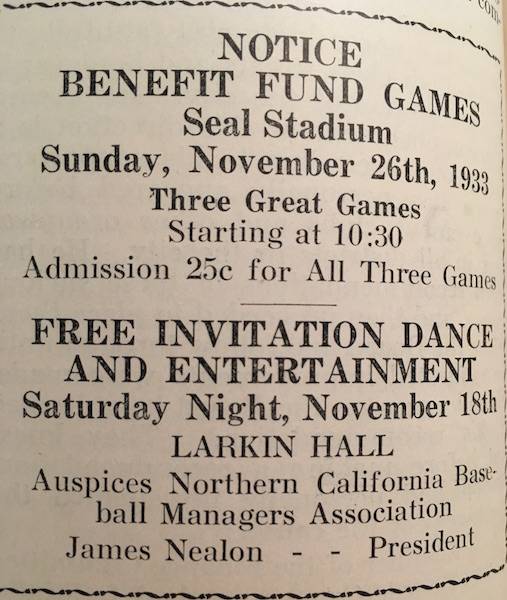

An advertisement for the 1933 benefit baseball game.

Photo: South of Market Journal, October 1933

Sporting events were very popular amongst members. Along with various other organizations, the SOM Boys hosted various charity old timers’ baseball games. The 1933 event featured the likes of Lefty O’Doul, Tony Lazzeri, and Joe Cronin, and was played at Seal Stadium.

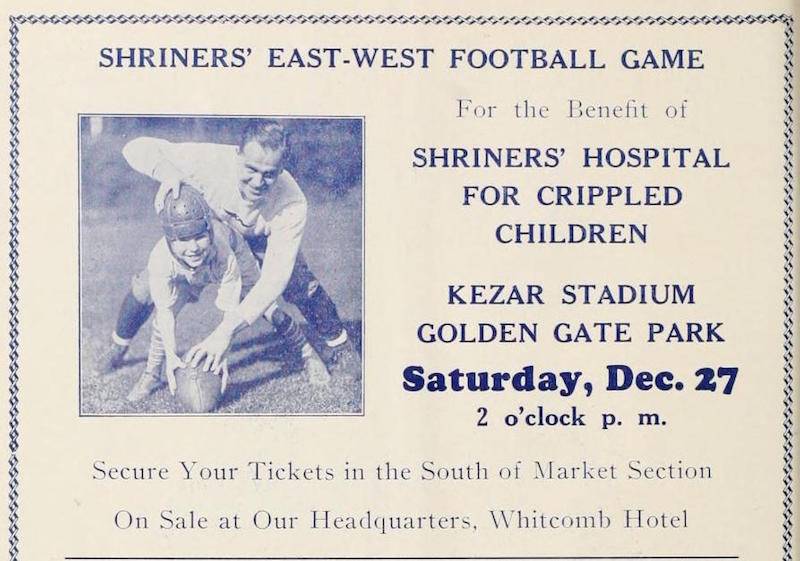

An advertisement for the 1930 East-West Shrine Game. Held annually since 1925, it was played in the Bay Area until 2007. As of 2020 it is held at Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Photo: South of Market Journal, December 1930

They also helped Shriners North America, another fraternal group, organize the East-West Shrine Game throughout the 1930s at Kezar Stadium, which showcased the nation’s best collegiate football players of the day.

Many SOM Boys were men of influence. Examples include “Sunny Jim” Rolph, onetime mayor of San Francisco and governor of California; Angelo Rossi, another San Francisco Mayor; Harry Heilmann, the Hall of Fame baseball player; and David Warfield, the internationally renowned actor and namesake of the theater on Market Street.

Some South of Market Boys on Mother's Day, 1946. From left to right: Peter Maloney, Hattie Diety, Ray Schiller, Elizabeth Harang, William Benn, and Harriett Hill.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

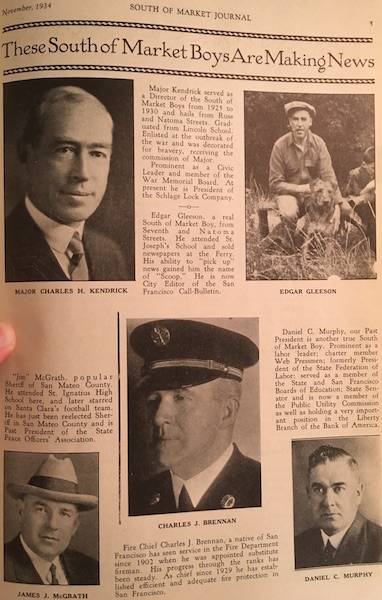

While recognizable names such as these called themselves South of Market Boys, someone like Peter Maloney, the founder himself, was a more typical example of a prominent member. Born to Irish parents, his father ran the Cuckoo’s Nest bar. Maloney grew up to become a distinguished police inspector, and today, the 4th street bridge is named in his honor. Along with his brother, the Maloney’s are but one example of the increased upward mobility that many South of Market Boys experienced in this time. Others include Chief of Police William Quinn, Fire Chief Charles Brennan, and many other judges, supervisors, and state senators. The list of SOM Boys in key positions of government and industry could go on. However, most of the 3,500 plus members were “working men”, and that is what made the SOM Boys truly influential. In every industry imaginable in San Francisco, there was bound to be a South of Market Boy, whether he be a leader or not. For every preeminent man, there were many more teachers, teamsters, longshoremen, tailors, railroad men, and small business owners of all kinds. The SOM Boys were well represented in both law enforcement and unions. One can only imagine how the famous 1934 general strike strained the meetings that year.

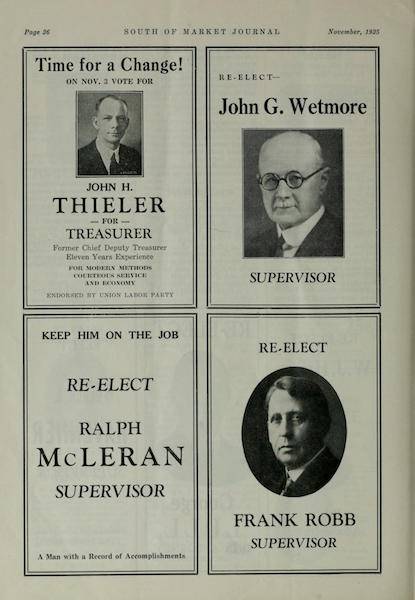

A few political advertisements in an issue of the South of Market Journal.

Photo: South of Market Journal, November 1925

This pervasiveness made it more than a club founded just for old times sake. It was a vehicle for networking, a space for political maneuvering, an avenue to reconnect with some of the most connected men in the City, who happened to be those old neighborhood kids. Proof of this exists in their surviving journals, where political articles and advertisements dot the pages. The support of an organization with 3,000 plus voters in San Francisco politics could be influential to say the least. Therefore, referring to them as just a drinking club or old timers’ club dismisses their position near the center of political and economic power of San Francisco.

Earthquake survivors pose in front of Lotta's Fountain in 1957. William Benn, former president of the South of Market Boys, hangs the wreath.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

As the generation who grew up "south of the slot" ceased to exist, so too did the South of Market Boys. Most memories of them have been lost to history, but everyone agrees that the SOM Boys were the first to establish the longstanding tradition of placing a wreath on Lotta’s Fountain on the anniversary of the great earthquake. Perhaps it is fitting that men so inextricably tied to April 18, 1906 are still remembered on that day.

A few noteworthy South of Market Boys

Photo: South of Market Journal, November 1934

On paper the South of Market Boys were similar to the many other fraternal groups that existed in American cities during that time. They threw parties, supported charitable causes, and managed to wield influence over city institutions. In this way, they are not unique. But maybe no other collection of people is so intertwined with San Francisco history like the SOM Boys. These men helped build and shape the city we know today, and as San Francisco constantly changes, they are a link to a working class culture that thrived in this city. Why are they largely forgotten? San Francisco is often romanticized as a bohemian haven, but that ignores the strong blue-collar tradition equally important to its history. If we talk about these roots, then the South of Market Boys should be included in that conversation.

Flyer for the Twenty-five Years After Ball.

Photo: South of Market Journal, April 1931

A few of their self-published journals are available to look at through the Internet Archive. They are some of the best sources we have left that specifically describe the old South of Market district, both physically and culturally. A link is provided below.

Men claimed membership to the South of Market Boys regardless of class. "The slot" referred to the cable car slots that lined Market Street. People living in South of Market were said to live "south of the slot."

San Francisco Examiner, February 13, 1925

SOURCES

Shaw, Annie. “Art Speaks: Love and Drama.” Nob Hill Gazette. May 4, 2019.

“Signals from Telegraph Hill.” San Francisco Westerners Corral, May 2017.

“Warren R. Maloney.” San Francisco Chronicle. May 4, 2014.

South of Market Journal, Aug. 1925 to Jul. 1926. San Francisco: South of Market Boys.

South of Market Journal, Dec. 1928 to Dec. 1930. San Francisco: South of Market Boys.

South of Market Journal, Jan. 1931 to Dec. 1934. San Francisco: South of Market Boys.