From Southeast Asia to the Tenderloin: Difference between revisions

m (added link) |

(fixed navigation) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

[[Sacramento and Franklin |Prev. Document]] [[Nob Hill | [[Sacramento and Franklin |Prev. Document]] [[Nob Hill and Pacific Heights at Turn of 20th Century |Next Document]] | ||

[[category:TenderNob]] [[category:Tenderloin]] [[category:Immigration]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:1990s]] [[category:Southeast Asian]] [[category:Vietnamese]] [[category:Cambodian]] [[category:Chinese]] [[category:Laotian]] | [[category:TenderNob]] [[category:Tenderloin]] [[category:Immigration]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:1990s]] [[category:Southeast Asian]] [[category:Vietnamese]] [[category:Cambodian]] [[category:Chinese]] [[category:Laotian]] | ||

Revision as of 21:42, 10 September 2021

Historical Essay

by Rob Waters and Wade Hudson

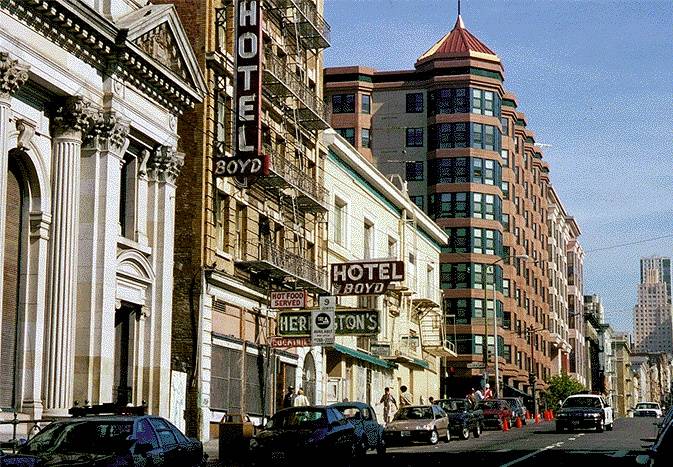

St. Anthony's at Jones and Golden Gate, behind Hotel Boyd, in the shadow of 111 Jones, a new affordable housing project built in the 1990s.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

At the same moment that the Tenderloin was rousing itself politically and beginning to pull together as a neighborhood, dramatic events on the other side of the Pacific Ocean began to make ripples, then waves in the Tenderloin. Starting in the late 1970s and intensifying in the early 80s, thousands of Southeast Asian refugees began arriving in the neighborhood. They were fleeing the violence and devastation of war, the squalor of overcrowded refugee camps, and the new communist regimes of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. The Tenderloin, with its supply of comparatively cheap rental housing became the principal settlement point of refugees landing in San Francisco.

This sudden influx of families and children made clearer than ever the critical lack of basic services for the residents of the Tenderloin. A concrete jungle with no parks, playgrounds, or greenery was now home to thousands of children. A community that had to depend for its grocery needs on corner stores with lots of liquor but little fresh food was now the home of large families, squeezed into studio and one-bedroom apartments, who wanted to buy fresh foods.

The dramatic demographic shift that took place in the neighborhood, and the community's new focus on organizing gave the neighborhood a stronger voice to advocate for itself, along with new resources to help meet its needs. One resource was the relative economic clout and entrepreneurial skill of the Southeast Asian community. Though most newly arriving Southeast Asians were desperately poor and had to depend on welfare benefits to survive, the Asian community's networks of mutual support allowed some families to open small markets where people could buy fresh vegetables, meat, and fruit, along with the specialty ingredients needed for Asian cooking. Today, there are a score of Asian-owned markets in the Tenderloin, and dozens of Vietnamese, Chinese and Cambodian restaurants.

excerpted from "The Tenderloin: What Makes a Neighborhood?" in Reclaiming San Francisco: History Politics and Culture, City Lights Books 1998