Crystal Palace Market: Difference between revisions

(linked to new photo essay on the market) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

[[Image:John-Gutmann Pop-Advertising,-San-Francisco 2000.127.71.jpg]] | [[Image:John-Gutmann Pop-Advertising,-San-Francisco 2000.127.71.jpg]] | ||

'''Advertisements on the side of the Crystal Palace Market, 1941 by John Gutman'' | '''Advertisements on the side of the Crystal Palace Market, 1941 by John Gutman''' | ||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6827'' | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6827'' | ||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAF-0023.'' | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAF-0023.'' | ||

''“The Palace was an emporium dedicated to the palates of the cosmos. It probably had food from Saturn. It was the FAO Schwarz of the stomach.”'' | |||

Thus author Gus Lee describes the Crystal Palace Market of his youth in ''China Boy''. | |||

His description is no exaggeration. During its 36-year run, the 71,000-square-foot market imported goods from at least 37 countries to provide the most varied offerings in the country. Its 65 shops included four dairy stands – selling 36,000 eggs daily – four poultry stands, six butcher shops, three fish markets, and seven fruit and vegetable stands. It featured a pet shop, a five and dime, two tobacco shops, and a phonograph record store. One stand sold only golden honey. When banks eliminated Saturday hours in 1953, the Crystal Palace Market promptly opened a check cashing service to meet its customers’ needs. | |||

[[Image: | [[Image:Fishing supply 1954 AAC-6889.jpeg]] | ||

''' | '''Fishing supply department at the Crystal Palace Market, April 14, 1954.''' | ||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC- | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6889.'' | ||

The Palace’s sporting goods store was one of the most diversified in the state. More copies of the New Yorker magazine were sold at the Palace Market’s newsstands than anywhere else in town except the St. Francis Hotel. A feed store, shoe repair, beauty parlor, flower stand, housewares store, photographer, locksmith, appliance store, catering department – all of these were available under its glass-latticed dome. Its fourteen eating establishments included Manning’s first San Francisco cafeteria and an Anchor Steam Beer stand. Few could argue with the Palace’s boast that it carried “Everything Under the Sun.” | |||

[[Image: Cash your paycheck 1953 AAC-6891.jpeg]] | |||

'' | '''Payroll check cashing booth at the Crystal Palace Market, was open six days a week, from 9:30 a.m. to 5:45 p.m. and charged 10 cents a check for the service, November 18, 1953''' | ||

'' | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6891.'' | ||

[[Image:Crystal palace AAC-6915.jpg]] | |||

'''Customer making a purchase from a meat stand in the Crystal Palace Market on its last day of business, August 3, 1959.''' | |||

'' | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6915.'' | ||

[[Image:Crystal palace AAC-6828.jpg]] | |||

'''Front of the Crystal Palace Market on Market Street, September 29, 1954.''' | |||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6828.'' | |||

[[Image:Crystal palace AAC-6862.jpg]] | |||

'' | '''Interior of the Crystal Palace Market, September 30, 1953.''' | ||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6862.'' | |||

[[Tour through Crystal Palace Market|Take a photo tour through some of the Crystal Palace Market stalls with the wide variety of offerings!]] | [[Tour through Crystal Palace Market|Take a photo tour through some of the Crystal Palace Market stalls with the wide variety of offerings!]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:51, 4 January 2023

Historical Essay

by Gail MacGowan, City Guides

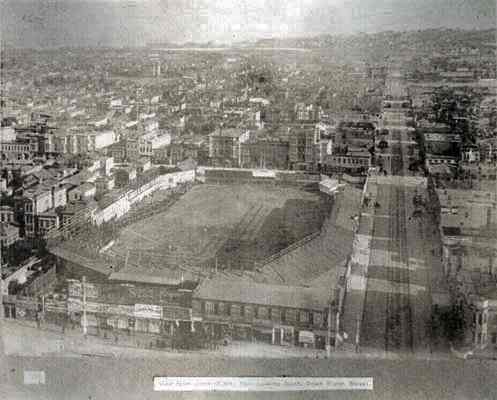

| Crystal Palace, a classic large center-city market, formerly at 8th and Market Streets, in a site that once housed a baseball stadium, and now is being extended vertically by a massive apartment complex being built by Angelo Sangiacomo's real estate empire. |

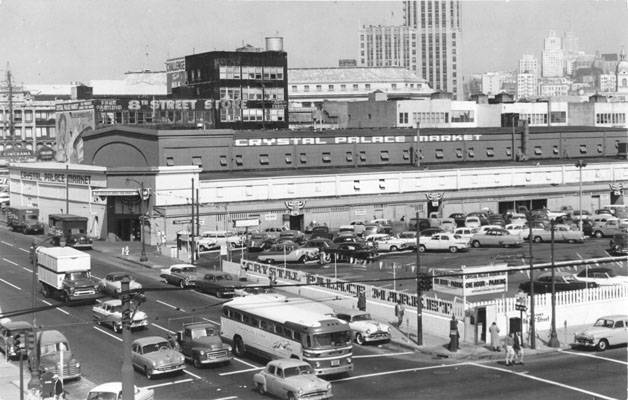

View of the Crystal Palace Market from 8th Street, showing the rear entrance and part of the 55,000 square foot parking lot, June 3, 1958

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6908.

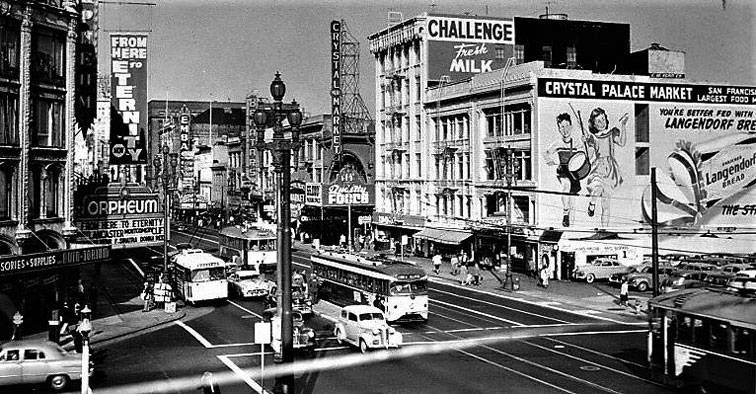

Crystal Palace Market and intersection of 8th and Market Streets, September, 1953.

Photo: courtesy Ben Campbell via Facebook

Waiting to buy New Zealand beef at Roy's Meats, 1953.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6851.

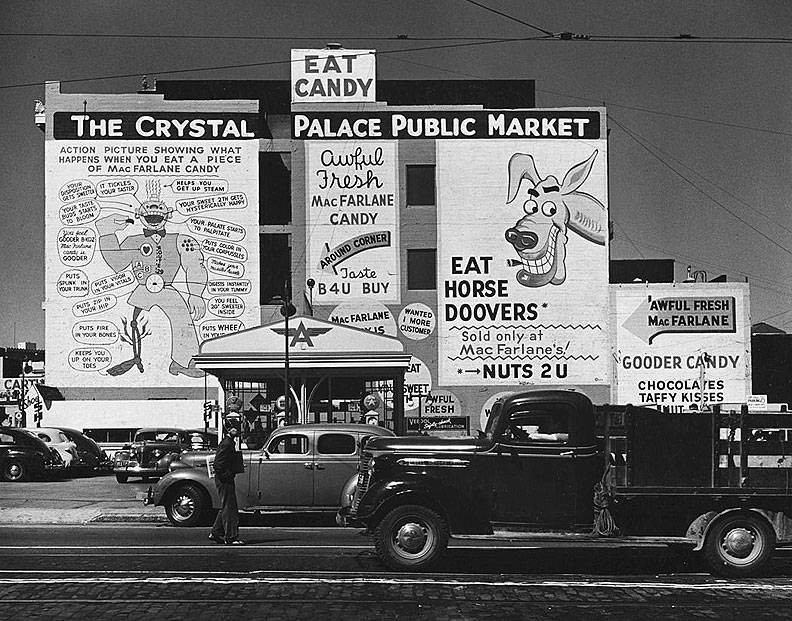

Advertisements on the side of the Crystal Palace Market, 1941 by John Gutman

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6827

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAF-0023.

“The Palace was an emporium dedicated to the palates of the cosmos. It probably had food from Saturn. It was the FAO Schwarz of the stomach.”

Thus author Gus Lee describes the Crystal Palace Market of his youth in China Boy.

His description is no exaggeration. During its 36-year run, the 71,000-square-foot market imported goods from at least 37 countries to provide the most varied offerings in the country. Its 65 shops included four dairy stands – selling 36,000 eggs daily – four poultry stands, six butcher shops, three fish markets, and seven fruit and vegetable stands. It featured a pet shop, a five and dime, two tobacco shops, and a phonograph record store. One stand sold only golden honey. When banks eliminated Saturday hours in 1953, the Crystal Palace Market promptly opened a check cashing service to meet its customers’ needs.

Fishing supply department at the Crystal Palace Market, April 14, 1954.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6889.

The Palace’s sporting goods store was one of the most diversified in the state. More copies of the New Yorker magazine were sold at the Palace Market’s newsstands than anywhere else in town except the St. Francis Hotel. A feed store, shoe repair, beauty parlor, flower stand, housewares store, photographer, locksmith, appliance store, catering department – all of these were available under its glass-latticed dome. Its fourteen eating establishments included Manning’s first San Francisco cafeteria and an Anchor Steam Beer stand. Few could argue with the Palace’s boast that it carried “Everything Under the Sun.”

Payroll check cashing booth at the Crystal Palace Market, was open six days a week, from 9:30 a.m. to 5:45 p.m. and charged 10 cents a check for the service, November 18, 1953

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6891.

Customer making a purchase from a meat stand in the Crystal Palace Market on its last day of business, August 3, 1959.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6915.

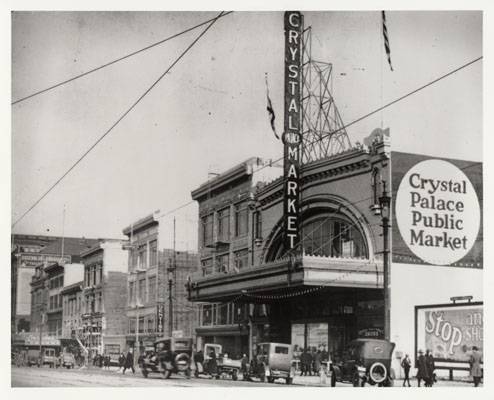

Front of the Crystal Palace Market on Market Street, September 29, 1954.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6828.

Interior of the Crystal Palace Market, September 30, 1953.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6862.

Liquor department at the Crystal Palace Market, September 30, 1953.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAC-6847.

When the Crystal Palace Market opened at Market and Eighth in 1923, the site was regarded as “out of town,” and raffles of automobiles were held to draw customers to the huge structure. Named for the historic Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park, the steel-framed, skylight-lit bazaar was a gamble that its huge central market could replace the corner grocery story. The market’s owners operated the grocery section, two liquor departments, two tobacco and magazine stands, and the appliance store, but the other 64 concessions were leased to individuals and firms. Three hundred people worked there.

The Market featured twenty-two entrances on five different streets: Market, Mission, 8th, Stevenson, and Jessie. Free parking was available in its 55,375-square-foot lot, or for 5¢ shoppers could arrive via the Municipal Railway’s Shoppers Special shuttle that traveled down Market from 2nd Street. Customers came from all walks of life – Queen Mother Nazli of Egypt came to shop there every day when she lived at the Fairmont Hotel – and drove to the Palace Market from as far away as Santa Rosa, Sacramento, and Merced. The Palace advertised “almost a country fair feeling in the air,” with clerks hawking their wares at the top of their voices to compete with strolling minstrels, an organ grinder and his monkey, and bands playing on the balcony. A gypsy fortune teller featured a parakeet who would pluck your fortune from her stack of cards. The Horseradish Man, red-eyed and weeping from grating his product, attracted wide-eyed children to his stand. Children also flocked to the peanut butter man for his free samples. Soap salesman Fred Wiedeman, stationed near the Market Street entrance, gathered crowds by letting his snakes crawl all over him, then demonstrated his wares to wash himself clean. Some Palace patrons recalled bootleggers at the back door and crap games with homemade beer in the basement.

View from Dome of City Hall, Looking South, Down Eighth Street, at Central Park, 1896.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, AAB-5897.

The four-acre lot at Market and Eighth had hosted crowds well before the Crystal Palace Market was built there. From 1874 to 1881, it was the site of the Mechanics Institute Pavilion where annual mechanics’ and manufacturers’ fairs were held. After that pavilion was demolished in 1881, the California Baseball League got its start at Central Park built on the lot. Shortly before the turn of the century, when the league outgrew the site, the park was replaced by the Central Theater, featuring touring shows and melodramas. It was destroyed in 1906, and for the next 16 years the empty “Circus Lot” hosted Ringling Brothers, Barnum & Bailey, and all the other big circuses and carnivals, plus a balloon ascension attraction.

In 1922, brothers Oliver and Arthur Rosseau bought the four-acre site and started their fabulous bazaar. Emporium-Capwell purchased it and the adjoining property in 1925; then in 1944 it was bought by 33-year-old Joseph Long of Alameda, who in the previous seven years had started a chain of drug stores. He “modernized” the huge market by breaking up its open spaces and building a large drugstore in one corner. But postwar tastes changed as families moved out to the suburbs. On August 1, 1959, the Crystal Palace Market closed its doors and was demolished to make room for the new $8 million, 400-room Del Webb TowneHouse luxury motel.

Sources: China Boy, Gus Lee (1991) Crystal Palace Market clipping file, San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

from City Guides website