Living in the UXA: The Universal Exchange Association: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' ''by John Curl, 1983'' Image:UXA cannery Bancroft.jpg '''The UXA cannery in Oakland, c. 1933.''' ''Photo: Bancroft Library'' {| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | colspan="2" |'''At the height of the Great Depression, a group of unemployed Oakland workers decided to take matters into their own hands. The system wasn’t working, so they set up...") |

(added link to curl's website) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | ||

''by John Curl, 1983'' | ''by John Curl, 1983, republished at [https://johncurl.net/living-in-the-uxa/ johncurl.net]'' | ||

[[Image:UXA cannery Bancroft.jpg]] | [[Image:UXA cannery Bancroft.jpg]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:32, 1 May 2023

Historical Essay

by John Curl, 1983, republished at johncurl.net

The UXA cannery in Oakland, c. 1933.

Photo: Bancroft Library

| At the height of the Great Depression, a group of unemployed Oakland workers decided to take matters into their own hands. The system wasn’t working, so they set up their own system. Money was nearly worthless, so they decided to live by barter. They called themselves the Unemployed Exchange Association and they soon went on to write a remarkable chapter in American economic history. This is their story. |

Ju1y 1932. The economy has stopped cold. Factories are locked, money is scarce. One out of seven Californians is unemployed. Social welfare programs are almost non-existent. Large numbers are destitute, hungry. Buildings stand vacant, boarded up. Food prices are next to nothing, but many thousands have nothing at all. California fields are rotting with tons of fruit and vegetables. Few farmers have money to pay harvesters; there is no market; many small farmers are losing their land. Thousands of children, women, and men have taken to the highways and rails, searching, for survival.

"Hoovervilles," shantytowns of the homeless, have sprung up around the country over the past three years. The largest in the Bay Area is "Pipe City," near the railroad tracks by the East Oakland waterfront, where hundreds live in sections of large sewer pipe that were never laid because the city ran out, of money. One of Pipe City's frequent visitors is Carl Rhodehamel. Once an electrical engineer at GE, a cellist, an inventor of several key technological developments in radio and early “talkies," an orchestra conductor, and a composer whose "Little Symphony" had once been a favorite with KGO fans, Rhodehamel is unemployed and down on his luck.

But not for long. There is a streak of genius in him that will 'sweep him out of Pipe City and into the leadership of an organization that will stir California and the country.

Rhodehamel and two others find an abandoned grocery store not far away, in Oakland’s Dimond-Allendale district that can be used for meetings. Soon a group of six unemployed men begin to meet and discuss ways out of their problems. All are skilled and experienced workers, but all realize it could be years, if ever, before they'll find work in their fields again. Since the system isn't working to provide their needs, they decide to form their own system. Since money is scarce, they dispense with money altogether. From now on they will try to provide themselves with everything they need to live by barter.

They begin by going door-to-door in the neighborhood, offering to do home repairs in exchange for "junk" from people's basements and garages. But to make their system really work they realize they'll have to grow larger. They distribute fliers, trying to gather all the unemployed in the neighborhood into the group.

On the evening of July 20, 1932, some twenty people meet at the Hawthorne School and organize the Unemployed (or Universal, as they'd later call it) Exchange Association, a title they immediately abbreviate to UXA. The X stands not only for exchange, but also for the "unknown factor" In an algebraic equation.

The UXA offers a new social equation to one neighborhood in Oakland—one whose echoes will soon be heard around a nation desperate for change.

I first heard of the UXA in 1978. It was election time at the Berkeley Co-op, and I was looking at photos and statements of board candidates in the Co-op News. Alongside a picture of a thoughtful ageless face, surrounded by a long mane of white beard and hair, was a candidacy statement different from all the rest. It began with a description of the UXA, and went on to call for the Co-op to expand its role as a marketing organization by undertaking the "ownership of the natural resources used to produce most of the goods it sells." The candidate pointed out that "time-killing" had been a fatal disease for the UXA and chided the reigning Co-op establishment for a similar affliction. The candidate's name was Oser Price.

The UXA sounded so unusual that I cut out Price's statement and saved it. I don't remember if I voted for him but as he said to me later, "I didn't run to get elected; I ran to get this information out."

A couple of years later at an Oakland Museum exhibit of California history in photography, I saw several pictures of the UXA taken by Dorothea Lange. My interest caught, I began rummaging through card catalogs in various East Bay libraries for more information, and. discovered a surprising wealth of literature written in the early '30s about the "self-help movement" and' particularly about the UXA. I realized I had stumbled upon an important but now forgotten corner of American history, a visionary social movement whose collapse had left artifacts scattered all over my own back yard...

“We are not going back to barter: we're going forward into barter. We're feeling our way along, developing a new science.”

- —Carl Rhodehamel

Their first focus was the neighborhood itself. They began by fixing up each other's homes and circulating unused articles of every variety among themselves, cycling the useless into the useful. There had been little work in the neighborhood in the three years since the crash of '29, so there was a great backlog of home repairs to be done. An abandoned grocery at 3768 Penniman became their first storeroom and commissary; it was soon overflowing with household and industrial articles. Broken items were repaired or rebuilt. The neighborhood, previously immobilized and choked with despair, was suddenly bustling with activity and confidence. People poured into the new organization.

They soon began sending scouts around Oakland and into the surrounding farm areas, to search out salvageable things they could acquire in labor exchange deals. Labor teams followed. All work was credited by a point system; one hundred points were awarded for an hour's work. UXA members exchanged points they'd earned for a choice of items in the commissary. Each article brought in was given a point value that approximated the labor time that went into it, with some adjustment for comparable monetary value. Many services were also offered for points, eventually including complete medical and dental care, auto repair, a nursery school, barbering, home heating (firewood), and some housing. At the UXA's peak it would distribute forty tons of food per week.

They called their system "reciprocal economy." They made no distinction in labor value between men and women, unskilled and skilled, lesser and greater productivity. Members could write "orders" (like checks) against their accounts to other' members for services provided. It was all done on the books, without a circulating script.

A General Assembly made up of all UXA members held final power. The assembly selected an Operating Committee in semi-annual elections, to coordinate the functions of the group. The UXA was divided into various sections: manufacturing, trading, food, farming, construction, gardening, homeworking, communications, health, transportation, bookkeeping, maintenance, fuel, personal services, placement, and food conservation. There was also a sawmill and a ranch. The headquarters' staff represented a section as well. Coordinators from each section met with the Operating Committee to form a Coordinating Assembly, the basic ongoing decision-making body.

The Operating Committee met four nights a week at the UXA's headquarters on East 14th Street at 40th Avenue. These were open meetings at which plans were hashed out in democratic discussions. Anybody with an idea—member or not—was welcome to sit in and was heard after the day's job commitments had been dealt with. The only rule was to speak one at a time.

On Friday nights the section coordinators joined in and formed the Coordinating Assembly. Oser Price was coordinator of the manufacturing section between '32 and '35. He describes the meeting: “The Coordinating Assembly had a big round table—nobody was at the head. There we held weekly brainstorming sessions. We could solve some of the most difficult problems by everybody tossing in their ideas—no matter how wild they were—and we would come up with answers that would work."

The section coordinators were appointed by the Operating Committee, with the workers in each section holding veto power. The coordinators had no authority over members; and could be recalled at any time. Power flowed from the bottom up. The workers in each section decided issues relevant to their work, approved or disapproved committee and assembly actions, and determined the admittance of new members into their section. Outsiders often expressed amazement at how well they functioned with no boss, foreman, or manager. In order to make decision-making viable, the numbers in each section were kept down to about twenty-five; when sections got much larger than that they split into two. "We were too busy," Oser Price says, “scratching around getting all the things we needed to survive to have many hassles."

News of the new organization quickly reached certain vigilant ears. Word was passed to the proper channels of the Oakland police department that the UXA was a "revolutionary" group with "Communist" leaders. Meetings were raided by the Red Squad. The commissary was once closed on the pretext that they were violating an ordinance prohibiting the sale of food and clothing from the same store. Utilities were shut off.

But the UXA bounced back, explaining to whomever would listen that organizing to barter was not the same thing as organizing to overthrow the government. Despite the harassment, the UXA grew, within only six months, to a membership of 1500. They began producing articles for trade and sale.

They set up a foundry and machine shop, woodshop, garage, soap factory, print shop, food conserving project, nursery and adult schools. They rebuilt eighteen trucks from junk. They branched outside of town maintaining a woodlot in Dixon, ranches near Modesto and Winters, and lumber mills near Oroville and in the Santa Cruz mountains.

UXA quilting workshop.

Photo: Bancroft Library

UXA printing operation.

Photo: Bancroft Library

A typical Coordinating Assembly meeting: Twenty-five women and men crowd about the huge round meeting table, elbows touching. Another twenty form a second circle around them. In the center of the table is a foot-high lighthouse; as its light revolves, the letters UXA flash. It's already past 8 p.m. Better get started; there's a lot to get done. The secretary takes down the day's commitments, detailed in an indexed looseleaf book and written on small yellow slips of paper. They go through the commitments one by one. What has been done and what not? What deals made? Which jobs have progressed, which have been finished? The different coordinators speak about their sections. They quickly go through twenty or thirty items. Fields have been harvested; trenches have been dug; wheelbarrows have been salvaged; cars have been painted; orders have come into the foundry; carpentering and plastering have been done; a deal has been made for wood; arms have been made for dental chairs; a contract to build a barn has been agreed on; a barge and tug have been leased to haul produce and wood; a group of apartments have been rented for labor and services; a wrecking deal has been discussed; an idle planing mill has been discovered; an order for office furniture has come in; a gasoline trade is in the works; a potato chip slicer is being converted for a sauerkraut project. Voorhies reports that a farmer near Hayward will trade sixty percent of his apricot and plum crops for harvesting labor. Can the UXA do it? Rutzebeck of personnel says labor is available. Hill is made coordinator.

Price of manufacturing reports that the swing saw bearings have been cast and are ready. Hanson says the saw needs a new motor. Llewellan knows of a motor but the owner wants a piano. Pugh says the trading section has one listed: they can get it for digging out part of a cellar, but it needs tuning. Is a piano tuner on the exchange list? Yes, three of them. After all the items are finished, there is a general discussion of ideas for new activities, how to get more labor power, and how to build leadership. By that time it is 11 p.m. and, since all have had their say, the chair, Rhodehamel, calls the meeting to a close.

But people linger afterward; discussion continues far into the night. Impressed with their success, they talk about how to implement barter on a social scale, so all who can find no place in the capitalist economy can join into cooperatives and create a new American way of life. They are convinced that a "reciprocal economy" could bring the whole country out of the Depression—from a USA of despair for the unemployed to a UXA of mutual aid and hope.

My search for the UXA ultimately led me back to the present: last spring I finally opened the phonebook and discovered, to my excitement, that there was a listing for Oser Price. I had to call several times before I caught him in. Oser at 82 leads a bustling, energetic life. Most mornings find him at a Laney College workshop practicing his welding, an art he has been developing in depth over the past few years; most evenings find him at one or another of his many involvements or at friends' homes. I found him eager to talk. His memories of those days, fifty years ago, seem scarcely dimmed or misplaced in his sharp mind. He remembers with particular clarity what it was like to be suddenly—and hopelessly—unemployed.

"When you were unemployed in those days, you were on your own (or on your friends). There weren't any benefits at all..."

“When, as a last resort, we join together to work for one another and share the result of that work, we make a great discovery: that the other's success is our own."

- —Carl Rhodehamel

UXA woodcutters.

Photo: Bancroft Library

The UXA was far from the only labor-exchange group in the Bay Area. It was part of what soon became a national phenomenon, a mass movement of "self-help'" or "unemployed" associations. In the summer and fall of 1932, at the same time as the UXA was forming, similar groups were organizing around the state and across the country—over one hundred in California alone. They appeared wherever conditions were ripe among the unemployed and underemployed, particularly near farming areas. It was truly a spontaneous mass movement, an idea whose time seemed to have come. By the spring of 1933, there were at least 100,000 members in about one hundred seventy-five groups in California, and another 50,000 in one hundred groups around the nation. Over the next two years, more than half a million people would be involved in at least 29 states. California was clearly in the forefront of the movement, with about two-thirds of the groups, many of the most successful ones, and (along with the Seattle area) some of the earliest.

Numerically, the largest concentration of self-help workers was in the Los Angeles–Orange County area, where about 75,000 people in 107 groups participated in the harvest of fall '32. Among the earliest southern groups were the LA Exchange, the Compton Relief Association, and the Unemployed Association of Santa Ana. Since farming areas were' easily accessible in the south, most of these groups were focused on produce, and organized large numbers of people to harvest in exchange for a share of the crop.

Meanwhile, there were about 32 self-help groups in the Bay Area: 22 in the East Bay, nine in San Francisco and the Peninsula, one in San Jose. The Berkeley Unemployed Association at 2110 Parker Street, had sections that included sewing, quilting and weaving, shoe repair, barbering. In addition, there was a wood yard, a kitchen and dining room, a commissary, a garage, a machine shop, a woodshop, and a mattress factory. At its height the BUA involved, several hundred people, arid had full medical and dental coverage. A visitor to the· wood shop in December '34 watched them working on office desks and furniture, as well as fruit lugs for the farm exchange section. Like many other groups, they later changed their name to the Berkeley Self-Help Cooperative; they no longer considered themselves unemployed.

A few blocks away on Delaware Street was the Pacific Cooperative League, which operated a garage, flourmill, wood yard, and store, as well as canning and weaving projects. It also ran a newspaper, the Herald of Cooperation, later called the Voice the Self Employed. The PCL laid claim to having organized one of the earliest labor exchanges of the Depression, when they traded an Atascadero rancher their harvesting labor for part of his apricot crop in September 1930.

The San Jose Unemployed Relief Council (later called the SJ Self-Help Co-op) was formed by a group of laid-off cannery workers. They soon had a wood yard, a fruit-and-vegetable drying yard, store, laundry, farm, soap factory, barbershop, shoe shop, commissary, sewing project, and contracted for a wide variety of jobs and services. At their height, they were about twelve hundred strong.

The Peninsula Economic Exchange, in Palo Alto, was organized by a group of unemployed white-collar workers, professionals, and bankrupt merchants. With about a hundred member families, 'they had a store on Emerson Street, a farm, a cannery, a wood yard, and a fishing boat. Unlike most of the other Northern California groups, they issued scrip—in-house currency—to members in exchange for hours worked. "Scrip exchanges" were more common at first in Southern California but were usually plagued with problems.

Self-help groups were bursting out all over in the early '30s, but none were more highly developed than the UXA, which most observers of the movement believe to have been the most successful self-help cooperative in America.

Oser Price was raised in the early days of the century near Colusa, a small Northern California town, and has lived all his life in this area. "I'd been working at Caterpillar Tractor as a tool designer," he told me. "The stock market crashed in October '29, and my job came to a grinding halt the next June. Fortunately, my wife was working as a night information operator at the phone company." Price spent the next two frustrating years looking for steady work or any work at all; they lived marginally off her small earnings. When they first heard of the UXA it had already been going for a number of months; it sounded good and they quickly joined. The organization was trying to jump into a program·of expanded production. They didn't take long to recognize Oser's broad understanding of industrial arts and skills and made him manufacturing coordinator. “I was in charge of the foundry, machine shop, soap-making; I had every sort of production under my jurisdiction.”

Time has not dimmed the pride that rang through Oser's voice, as he recalled this history. I was fascinated . . . .

With Roosevelt's New Deal came the Federal Emergency Relief Act (FERA). To the cooperatives, it was a mixed blessing. Carl Rhodehamel, H.S. Calvert of the Pacific Cooperative League, and other California leaders were called by the congressional committees drafting the bill to confer on provisions concerning grants to cooperatives for means of production. Due in part to their efforts, funds were suddenly available. Rhodehamel, however, argued—in vain—that they should not be outright grants, but loans repayable by labor exchange. Rhodehamel felt so strongly about the issue that he tried to prevent the UXA from applying for a FERA grant, out of fear of the strings attached. He was overruled by the membership. Still, although the feds considered it a grant, the FERA money was recorded in the UXA books as a loan.

By the end of 1934, FERA had distributed $411,000 to 81 groups. The UXA received grants for their sawmill, for printing equipment, gardening, and canning facilities. The Berkeley Self Help Co-op got money for their furniture, mattress, and shoe operations. The PCL used FERA grants for housing, milling, and weaving operations.

Though this federal money was welcome and helped the cooperatives expand their efforts, it also turned out that Carl Rhodehamel was right when he predicted that there would strings attached. FERA grants were used as a carrot to influence the internal affairs of many co-ops. A typical case was the San Jose Co-op, whose grants were held up due to the presence of a “radical faction” in the organization. This touched off a bitter struggle in the group. The “Reds” lost and the money came through.

Although FERA money proved to be a double-edged sword for the self-help movement, the co- ops survived it. The real kiss of death for the movement lay ahead: the WPA. But before that kiss descended, the co-ops were to spark one of the great grassroots electoral uprisings in American history.

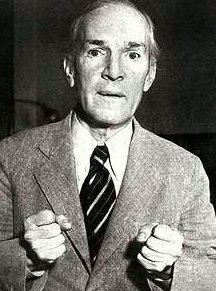

Upton Sinclair on cover of Time Magazine in 1934.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In September 1933, Upton Sinclair, novelist, chronicler of American social reality, and a long- time member of the California Socialist Party, suddenly changed registration and threw his hat into the ring for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination. He brought with him a program he called EPIC: End Poverty in California.

With “Production for Use” as its rally cry, the EPIC plan would have created state agencies to take over idle farms and production facilities and turn them over to the unemployed. Sinclair’s platform vowed to “establish State colonies whereby the unemployed may become self-sustaining . . . to acquire factories and production plants whereby the unemployed may produce the basic necessities required for themselves and for the land colonies, and to operate these factories and house and feed and care for the workers . . . , [to] maintain a distribution system of each other’s products . . . thus constituting a complete industrial system, a new and self-sustaining world for those our present system cannot employ.”

Public bodies—the California Authorities for Land, for Production, and for Barter—would preside, respectively, over rural, urban, and exchange activities. There were also provisions for a series of social welfare programs (there were virtually no state programs at the time), and for a general redistribution of the wealth downward through changes in tax laws.

End Poverty in California logo.

EPIC took its immediate inspiration from the self-help cooperatives, with the UXA as the classical model. To Sinclair, the cooperatives were living proof that these were not idle utopian dreams, but could actually work!

Hjalmar Rutzebeck, personnel coordinator of the UXA, took a leave of absence and became a key aide in the campaign. EPIC clubs sprang up around the state like grass after rain—ultimately 2000 of them. The EPIC News reached a circulation of 1.5 million.

Most of the cooperatives decided it was out of their sphere, as economic organizations, to formally endorse electoral candidates, even Sinclair. Sinclair agreed. But large numbers of members worked on the campaign. "Of course 'self-help' was production for use," Sinclair said later, "and those people, automatically became EPICs."

Sinclair had garnered 50,000 votes running for governor as a socialist four years previously. Now he swept the 1934 Democratic primary with 436,000 votes, more than the other six candidates, combined. But the California Right, entrenched for decades, had not yet begun to fight.

After the primary upset, most of the Democratic old guard defected to the Republicans; the state organization ceased to be of any support. The news media, which at first had usually reported favorably on the self-help movement and on Sinclair, now turned around and attacked without quarter. Almost every newspaper and radio station came out against him. An anti-EPIC newsreel was shown in every theater in the state. Gigantic sums of money were spent to defeat Sinclair in possibly the most vicious and libelous campaign in California history.

Sinclair countered by going to Washington for support. Roosevelt—in office only a year and a half—had decided not to single out any particular Democrat for special endorsement. Sinclair noted that did not exclude his endorsing any particular plan. He conferred with Harry Hopkins, the relief administrator who was later to set up the WPA. Hopkins announced that he was ready to work with EPIC; he presented it to FDR as a potential national plan. Sinclair wrote of his meeting with the President:

“At the end he told me that he was coming out for ‘production for use.’ I said, ‘If you do that, Mr. President, it will elect me.’ ‘Well,’ he said, ‘I am going to do it.’”

FDR indicated he would come·out for the plan during a nationwide radio address scheduled for the week before the election and Sinclair hinted publicly that this would happen. On the night of the broadcast, the entire EPIC movement was at its radios. When Roosevelt signed off, few could believe the speech was over, and he'd said nothing about production for use. A mood of doubt suddenly permeated the campaign where optimism had reigned.

Sinclair's antagonist was incumbent governor Frank Merriam, seventy years old and somewhat senile, who'd saved himself from being dumped by his own party by his violent suppression of the San Francisco longshore (and later general) strike, which had taken place shortly before. He suddenly became the darling of the reactionary right.

Sinclair got almost 900,000 votes, 37 percent of the votes cast; Merriam got 49 percent, and a third party candidate got the difference. Sinclair was told later that there was a gunman waiting at his campaign headquarters; he was told he would have been shot if he'd won.

The EPIC uprising, even in electoral defeat, took much of the bite out of the state's right wing for decades afterwards. The reflection of many of EPIC's proposals can be seen in later New Deal programs.

Sinclair went on to offer a national version of EPIC, win a Pulitzer Prize for fiction and later was nominated for a Nobel Prize by a group that included Mahatma Gandhi, George Bernard Shaw, and Bertrand Russell. In 1936, Sinclair published a thinly fictionalized history of the UXA, the Self-Help movement, and EPIC, entitled, Co-op: a Novel of Living Together. He uses Hjalmet Rutzebeck, "the Alaskaman," as the model for his protagonist. Rutzebeck himself wrote a novel about his experiences in the UXA and EPIC, Hell's Paradise (1946).

After the defeat, EPIC leaders split on what to do next. While Sinclair took off on a national speaking tour, a group led by Frank Taylor set up a Production for Use Committee and worked to turn the EPIC energy into a consumer co-op movement. The consolidation of buying power would be a step to gaining control of the economy, they hoped.

A large number of EPIC groups planned buying clubs and stores; by the fall of 1935, there were 210 consumer co-ops in California, with 50,000 members—almost all the groups newly organized. Among the most successful at first was New Day Co-op in Oakland, with fourteen hundred members and Producers-Consumers Co-op at 668 Haight Street in San Francisco. But these and the great majority of others quickly collapsed.

Former members of New Day, however, became leaders in Pacific Co-operative Services, organized in 1936. In January of the next year, they opened a tiny store at 2489 Shattuck Avenue to which today's Berkeley Co-op, with around 100,000 member families, traces a central root.

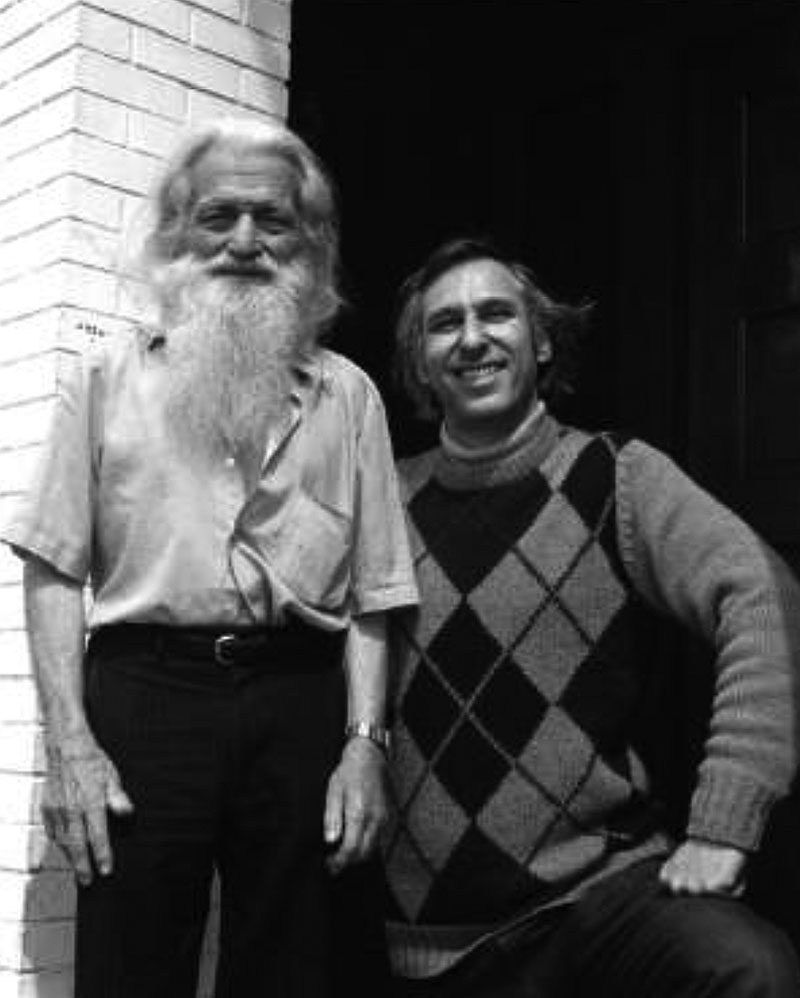

One Sunday morning Oser Price, myself, and my photographer friend Michael Ghelerter squeezed into a little car and zipped down Ashby onto the freeway to East Oakland. Our plan was to tour the main sites of UXA activities, see what was there now, and try to get a few good pictures.

Oser Price and John Curl (author) in 1983.

Photo: Michael Ghelerter

We turned off the freeway at Hegenberger Road and cruised down 85th Avenue looking for the site of the old foundry. We finally stopped at an open field covered with weeds and broken foundations and climbed out. I followed Oser, who is about half my size, back and forth around the cracked concrete slabs and rubble. He seemed a bit uncertain at first, then stopped. "This is the spot the foundry was on. Syd Splain made a cupola for it out of large oil drums. It wasn't a very big foundry, but we did a lot of casting. This made the basis for getting all of our dental and medical supplies. We made brass and bronze and aluminum castings for a supply company in trade."

Then it was on to the site of the Operating Assembly. As we drove down East 14th Street, Oser remarked about how much the ethnic makeup of the neighborhood had changed, that the large black and Latin population had not arrived until World War II. "I don't remember any blacks in the UXA at all. They would have been welcome, but they just weren't around here then.”

The building where the Operating Assembly met is still there, at 40th Avenue; it's a Volvo dealership today. Being Sunday, it was locked and we couldn't get in. "The Assembly room was downstairs in front and the dental lab in back. Upstairs was medical and dental offices, and some living quarters," Oser said.

Not far away was "Smiley" Gilbert's old house, a quaint little wood frame structure perched on top of a hill where many UXA folks used to come to socialize after hours. Smiley was the main organizer of the Santa Cruz Mountains lumbering operation.

From there we drove to 35th and Penniman, to see a parking lot that has taken the place of the UXA commissary and crafts store. We circled Lake Merritt to 9th Street and Oak, and stopped at an apartment building, predominantly Chinese today, that the UXA had taken over, exchanging carpentry for rental credits.

Oser spoke of other sites we didn't get to: "Down on High Street near the estuary, there was this big warehouse where we produced our sauerkraut and had our soap factory. There was a shed not far from it, where we had our garage. We had good competent mechanics and good tools. I rebored an eight cylinder engine there.” Sauerkraut, because of the ready availability of lots of cabbage, became a UXA staple. "They were cutting sauerkraut with hand cutters—pretty slow,” Oser recalled. "I spotted an old potato chip slicer that was sitting out in the back yard of a company in East Oakland. The manager said it wasn’t fast enough for commercial production, so for thirty hours work we got it. We went from making sauerkraut from the bucket to by the barrel."

The thing that' killed the UXA was the cash flow from the WPA. It drained off people who needed money—and everybody did need some. People couldn't be in both the UXA and in WPA at the same time. Those who had to have cash took WPA. Soon there weren't enough people available to make the UXA work.

- —Oser Price

The Works Progress Administration of 1935, promising a cash job at a decent wage to every unemployed person able to work, undercut the entire self-help movement. Members had to choose between the limitations of barter or an assured cash income. (Only one tenth of one percent of UXA transactions had been in cash.)

Carl Rhodehamel tried to prevent a mass exodus from the UXA by arguing that these government programs would be temporary, and members would have no cooperative to come back to when WPA was shut down. Nonetheless, the exodus took place. Hundreds of groups around the country collapsed. The UXA, like the rest, faced a sudden labor shortage. They now had difficulty delivering on work promised, and fell deeper and deeper into a hole. Rutzebeck describes the situation in Hell's Paradise:

“Svend Norman made the rounds at the local relief centers. Here he saw, standing in line to be registered, workers and former workers from UXA PCL, BUA, UCRA, and all the other groups; while at headquarters, calls went unheeded for workers….”

Rhodehamel accused the federal government of wanting the cooperatives to fail, and Sinclair pleaded with Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins to get work in the cooperatives declared to count as WPA hours. It was all to no avail. Sinclair wound up calling WPA an "arch-enemy of self-help."

The administration probably really didn’t want independent cooperatives as a permanent part of the economy. Still, the New Deal was far from the only problem the movement faced. Besides the usual personality clashes and leadership disputes that are a fact of life in all organizations, especially democratic ones, the co-ops were beset by a number of particular difficulties.

In production-oriented groups, such as the UXA, productivity was an on-going problem. When the group decided that all work would be worth the same on a time basis, they hoped that spirit and education would make up for inevitable unproductive attitudes in some members. But despite weekly classes, the UXA "School of Reciprocal Economy" was never able to overcome the "employee mentality" of some members, who tried to put in as many hours as possible without care to productivity. The result was the piling up of more points on the books than the organization had products to redeem them for. Meanwhile, the scavenging operations of the co-ops inevitably diminished as their work eventually depleted the surplus products in their areas.

The high turnover rate of younger members was also a problem. Young people tended to move on when they found job openings, while the older, largely "unemployable" members tended to stay in the co-ops for the long run. The result in some instances was a dearth of muscle power. At one point, the median age of the UXA was 48.

And then the young men found another occupation.

If there must be war, then our movement will have to wait for the fever of that war to run its course …. But all wars end, and when this one is ended, five, ten, or fifty years from now, we or such as we will again proceed ….

- –Carl Rhodehamel

Although Roosevelt's programs alleviated some of the problems of the depression, the "New" Deal turned out to be temporary, and California, like the nation, slumped back into lethargy as the late '30s progressed. The WPA ended, but the self-help movement did not revive, as the country and the world braced for war.

World War II finally snapped the economy out of depression, created full employment, and gave birth to the mighty industrial machine that emerged at war's end. By that time Carl Rhodehamel and many of the others who made the movement were no longer with us, and the movement on which they'd pinned their hopes and dreams was but a faint memory. Still, questions remain: If the government had not undercut the cooperatives, would they have become a permanent part of our economy? What if EPIC had won: could it have actually ended poverty and unemployment?

Rhodehamel believed that the primary reason cooperatives were needed was that a growing body of people was being permanently displaced by technological changes. The ranks of the unemployed in the '30s were filled with highly trained and skilled people who would never find jobs in their fields again, particularly middle-aged people. Today that process has accelerated; we are being told continually to prepare ourselves for a permanent situation of high unemployment.

If the US continues to change from a production economy to a service economy (with multinational firms shifting their production to the Third World, primarily Asia), a permanent underclass of unemployed, underemployed, and never-employed will continue to be formed here. Self-help associations are a natural organizational form springing from people in this situation, just as labor unions are natural for the employed.

Could the unemployed rise today in a similar movement?

There are already groups of the unemployed in the Bay Area, although none has turned to barter or labor exchange in a major way. The money system today is not stopped dead as it was in '32'. Still, a close parallel to the production side of self-help cooperatives can be found in today's work collective movement, of which the Bay Area is probably the most developed center in the nation. The most recent Bay Area Directory of Collectives, published by a local networking' organization, the InterCollective, lists over two hundred work collectives, participating in a wide variety of activities.

“Consider this," says Oser Price today, fifty years later. “All of us work a certain amount of time or produce a certain amount, whatever it takes to produce a minimal survival. Beyond that everybody's on their own and can produce or make all they can. That way you don't squelch creativity or initiative. To reduce bureaucracy to zero, you have to have as much as possible of what's done and how it's done in the hands of the people who are doing it. Worker ownership, that's the key. I don't care how big the organization, if you have nothing but worker ownership, it'll work. It can happen if you make it happen: it's all up to you."

Our tour stopped at 532 16th Street in downtown Oakland where, fifty years ago, the UXA had maintained offices on the second floor. We met a young woman at the front door who turned out to be one half of the couple managing what today is an apartment building. She let us in and showed us around. I watched as Oser Price walked down the hall he'd trod half a century earlier. He stopped at a window by the fire escape and stood there a minute gazing wistfully out. There was a faraway look in his eyes, and on his lips an almost imperceptible smile.

From the East Bay Express, Friday, November 11, 1983—Volume 6, Number 5