TOM MOONEY: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(upgraded video) |

||

| (31 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

''by Chris Carlsson'' | |||

[[Image:labor1$preparedness-day-1916.jpg]] | [[Image:labor1$preparedness-day-1916.jpg]] | ||

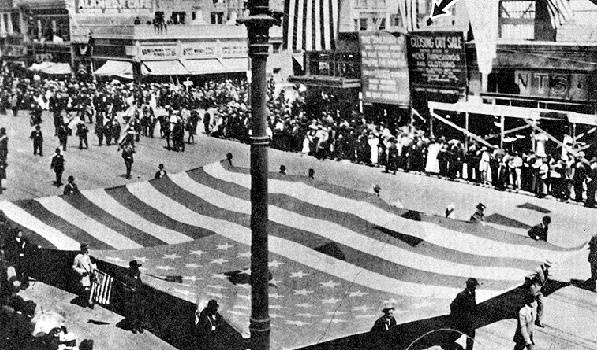

'''Market and Steuart Streets moments before the Preparedness Day Bombing, July 22, 1916. This picture was suppressed by the prosecution for 20 years. The arrow points to what some think may have been the actual bomber.''' | '''Market and Steuart Streets moments before the Preparedness Day Bombing, July 22, 1916. This picture was suppressed by the prosecution for 20 years. The arrow points to what some think may have been the actual bomber.''' | ||

''Photo: courtesy Bancroft Library'' | |||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''On July 22, 1916, the "Preparedness Day" parade through San Francisco—organized by anti-union city and business officials to rally support for US participation in WWI—was bombed in the worst attack in San Francisco history. The District Attorney's office, which had close ties with business interests opposed to unionism, accused labor leaders of being the perpetrators. In particular, they singled out Tom Mooney, an infamous militant San Francisco labor leader, and sentenced him to the death penalty despite having evidence of his innocence. It took pressure from President Wilson to commute the death sentence, and a further 22 years in jail for Mooney to be pardoned.''' | |||

|} | |||

July 22, 1916 "Preparedness Day:" A turning point in labor history for San Francisco and perhaps for the entire United States. | July 22, 1916 "Preparedness Day:" A turning point in labor history for San Francisco and perhaps for the entire United States. | ||

A large parade up San Francisco's Market Street had been organized by the Chamber of Commerce and the conservative business establishment to drum up patriotism and support for U.S. entry into the European war (WWI). In addition to the war in Europe, U.S. troops were already gathering at Nogales to invade Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa, Irish | A large parade up San Francisco's Market Street had been organized by the Chamber of Commerce and the conservative business establishment to drum up patriotism and support for U.S. entry into the European war (WWI). In addition to the war in Europe, U.S. troops were already gathering at Nogales to invade Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa, Irish immigrants were busy raising money and arms to support Irish independence, just three months after the Easter Rebellion in Ireland, a bloody strike on San Francisco's waterfront had killed a man and left dozens injured only a month earlier. At 2:06 pm, as marchers were entering Market Street from Steuart, a bomb exploded, killing ten and critically injuring 40 more. | ||

A militant San Francisco labor leader, Tom Mooney, his wife Rena, a radical worker named Warren K. Billings, and two others were soon charged with the crime. Then District Attorney Charles Fickert had been elected in 1909 with a secret fund of $100,000 put up by United Railroads, a company formed in | A militant San Francisco labor leader, Tom Mooney, his wife Rena, a radical worker named Warren K. Billings, and two others were soon charged with the crime. Then District Attorney Charles Fickert had been elected in 1909 with a secret fund of $100,000 put up by [[United Railroads|United Railroads]], a company formed in 1903 when Patrick Calhoun bought up most of the city's streetcar lines and merged them into one company. One of DA Fickert's first acts was the dismissal of corruption charges pending against Calhoun, his chief counsel and his chief assistant, thereby ending the famous graft trials which had brought down political boss [[Abe Ruef and the Union Labor Party|Abe Ruef]] and previous Mayor Schmitz. | ||

[[Image:Labor-mooney-alibi-photo.jpg]] | |||

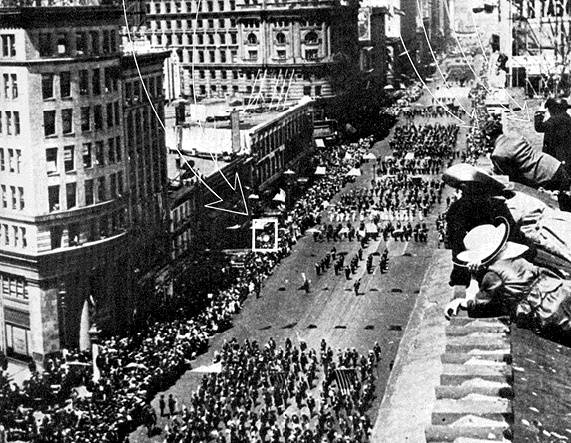

In late 1915, Mooney had targeted the | '''Tom Mooney had real evidence of his innocence, but was denied a new trial or pardon for 22 years. At 2:01 p.m. on July 22, 1916, a photo by Wade Hamilton places Tom and Rena Mooney on the Eilers Buildng at 975 Market, at the time they were allegedly placing the bomb a mile east at Steuart and Market. This photograph was in the possession of the prosecutors but was never presented at trial.''' | ||

''Photo: courtesy Bancroft Library'' | |||

Mooney had been a major actor in numerous strikes and organizing campaigns. By the end of 1915 he'd become a thorn in the side of the San Francisco Labor Council as much as the Chamber of Commerce with his radical calls for industrial unionism; Pacific Gas & Electric and its then subsidiaries (San Joaquin Light & Power Co., Western Electric Co., [[Rising Tensions Engulf 1916 San Francisco: Class War Precedes World War I|Sierra & SF Power Co.]]) considered him a dangerous foe after a big strike from May 1913 through January 1914. | |||

[[Image:1908-socialist-1st-Tom-Mooney-3rd-from-right-Eugene-Debs.jpg]] | |||

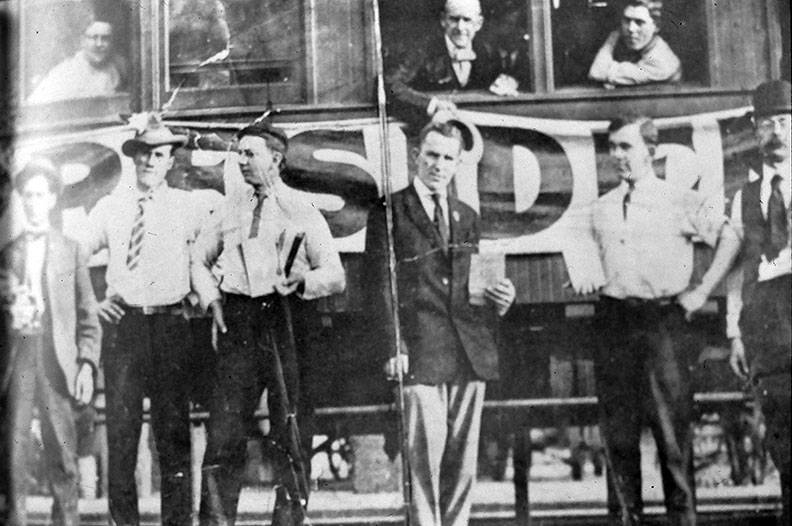

'''1908 photo of radicals, including Tom Mooney, 2nd from right, and Socialist Presidential candidate Eugene Debs, third from right.''' | |||

''Photo: provenance unknown'' | |||

In late 1915, Mooney had targeted the anti-union [[United Railroads|United Railroads]] for organizing. In 1916, California had two major cities, San Francisco and Los Angeles, the former known as the most unionized city in America, the latter as a bastion of conservatism and the most open shop (i.e. non-union) city in the country. San Francisco's Chamber of Commerce keenly felt the difference, as new investment was mostly heading south to Los Angeles and the land of cheap, abundant labor. | |||

Between June 9, 1916 and July 17, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce claimed that 38 "non-union workers" [scabs] were sent to the hospital because of attacks by striking longshoremen. Two strikers were dead. In this violent atmosphere the Chamber issued its first public endorsement of the open shop on June 22, 1916. On July 10, a meeting of over 2,000 merchants packed the floor of the Merchant's Exchange and endorsed the creation of a standing [[Law and Order Committee|"Law and Order Committee]]" of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce to "rid San Francisco of anarchistic elements." By year-end the Law and Order Committee had a fund at its disposal of $1 million. | Between June 9, 1916 and July 17, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce claimed that 38 "non-union workers" [scabs] were sent to the hospital because of attacks by striking longshoremen. Two strikers were dead. In this violent atmosphere the Chamber issued its first public endorsement of the open shop on June 22, 1916. On July 10, a meeting of over 2,000 merchants packed the floor of the Merchant's Exchange and endorsed the creation of a standing [[Law and Order Committee|"Law and Order Committee]]" of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce to "rid San Francisco of anarchistic elements." By year-end the Law and Order Committee had a fund at its disposal of $1 million. | ||

Behind the scenes was one Martin Swanson, a detective with a long involvement in strikes, and various labor confrontations in San Francisco, mostly working for PG&E, the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Co. (later PacBell), and other utilities and railroads. Swanson had spent a couple of months trying to frame Mooney for a bombing of PG&E power lines just south of San Francisco on San Bruno mountain, offering bribes of $5,000 to several of Mooney's allies. He also maintained constant surveillance and harassment of Mooney, Billings, and the anarchists Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman, who were living at 569 Dolores in the Mission District. | Behind the scenes was one Martin Swanson, a detective with a long involvement in strikes, and various labor confrontations in San Francisco, mostly working for PG&E, the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Co. (later PacBell), and other utilities and railroads. Swanson had spent a couple of months trying to frame Mooney for a bombing of PG&E power lines just south of San Francisco on San Bruno mountain, offering bribes of $5,000 to several of Mooney's allies. He also maintained constant surveillance and harassment of Mooney, Billings, and the anarchists [[Goldman and Berkman in SF|Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman]], who were living at 569 Dolores in the Mission District. | ||

[[Image:Tom mooney innocent 001.jpg]] | |||

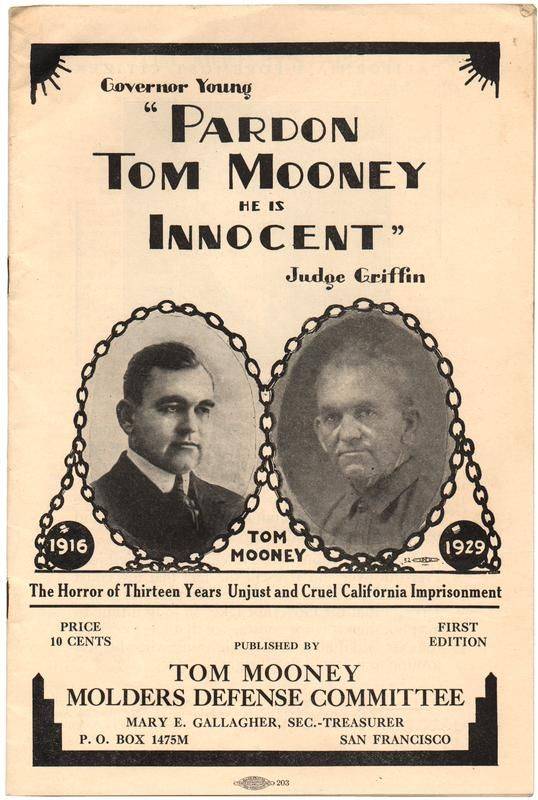

'''One of the many efforts to publicize the Mooney case, this one in 1929.''' | |||

[[Image:labor1$mooney-in-san-quentin.jpg]] | |||

READ MORE: | '''Tom Mooney in his cell in San Quentin (c. 1932)''' | ||

''Image: Bancroft Library'' | |||

[[Image:Mooney in sf jail.jpg]] | |||

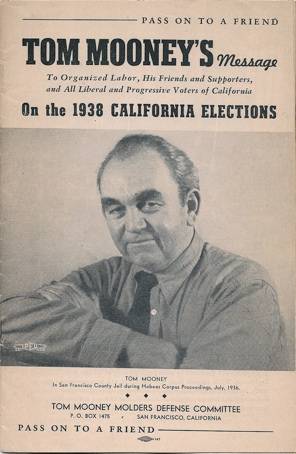

'''Agitational writing in 1938 that successful led to Mooney's pardon in 1939 by new Governor Culbert Olson.''' | |||

After the Preparedness Day bombing, Swanson was appointed as investigator for the (clearly corrupt) District Attorney that same evening. Over the next two years it was gradually revealed that Martin Swanson was the man primarily responsible for finding and coaching false witnesses against Mooney and Billings. Tom Mooney was tried first, and based on the false evidence, convicted of first degree murder and given the death sentence. Some time later Warren Billings was tried, and though some of the testimony had already been discredited, he too was convicted of first degree murder but given a life sentence. The three other alleged co-conspirators were tried later and all acquitted as the fraudulent case against them had collapsed by then. | |||

Mooney had his death sentence commuted to life in prison by California's governor under pressure from President Woodrow Wilson in 1917. It took another 22 and a half years before Tom Mooney was granted an unconditional pardon by newly-elected liberal Democratic governor Culbert Olson in January, 1939. Warren Billings would receive his release from prison in 1942. | |||

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/ssfMOONEDT1" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | |||

'''Mooney appeals for his release in 1933 (video)''' | |||

'''READ MORE:''' | |||

''Frame-up'' by Curt Gentry, © 1967, WW Norton & Co., New York. | ''Frame-up'' by Curt Gentry, © 1967, WW Norton & Co., New York. | ||

| Line 29: | Line 67: | ||

''Life of an Anarchist: The Alexander Berkman Reader'', ed. Gene Fellner, Four Walls Eight Windows, New York: 1992. | ''Life of an Anarchist: The Alexander Berkman Reader'', ed. Gene Fellner, Four Walls Eight Windows, New York: 1992. | ||

[[ | [[San Francisco’s Haymarket: A Redemptive Tale of Class Struggle |More on Tom Mooney]] | ||

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/chamber-of-commerce-preparedness-day-film-llsf-2015-20151208-30p-7-mbps" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | |||

'''Chamber of Commerce propaganda film to warn population.''' | |||

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/tom-mooney-returns-1939-llsf-2016-20-mbps-1" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | |||

'' | '''Footage of Tom Mooney on his long-awaited return to San Francisco after 22.5 years in jail for a bombing in 1916 he had nothing to do with. He was pardoned by new governor Culbert Olson and made his way back to SF's Ferry Building where he was greeted by 10,000 people. The city accompanied him on his walk up Market to the Civic Center and this footage was shot near the end of the parade.''' | ||

''Video: from "Lost Landscapes 11, 2016" edited by Rick Prelinger, courtesy Prelinger Archives'' | |||

<hr> | |||

[[Image:Tours-labor.gif|link=CLASS CONFLICT IN S.F.]] [[CLASS CONFLICT IN S.F.| Return to beginning of Labor History Tour]] | |||

[[Abe Ruef and the Union Labor Party |Prev. Document]] [[ | [[Abe Ruef and the Union Labor Party |Prev. Document]] [[San Francisco’s Haymarket: A Redemptive Tale of Class Struggle |Next Document]] | ||

[[category:Labor]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:downtown]] | [[category:Labor]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1910s]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:downtown]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:48, 4 November 2023

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

Market and Steuart Streets moments before the Preparedness Day Bombing, July 22, 1916. This picture was suppressed by the prosecution for 20 years. The arrow points to what some think may have been the actual bomber.

Photo: courtesy Bancroft Library

| On July 22, 1916, the "Preparedness Day" parade through San Francisco—organized by anti-union city and business officials to rally support for US participation in WWI—was bombed in the worst attack in San Francisco history. The District Attorney's office, which had close ties with business interests opposed to unionism, accused labor leaders of being the perpetrators. In particular, they singled out Tom Mooney, an infamous militant San Francisco labor leader, and sentenced him to the death penalty despite having evidence of his innocence. It took pressure from President Wilson to commute the death sentence, and a further 22 years in jail for Mooney to be pardoned. |

July 22, 1916 "Preparedness Day:" A turning point in labor history for San Francisco and perhaps for the entire United States.

A large parade up San Francisco's Market Street had been organized by the Chamber of Commerce and the conservative business establishment to drum up patriotism and support for U.S. entry into the European war (WWI). In addition to the war in Europe, U.S. troops were already gathering at Nogales to invade Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa, Irish immigrants were busy raising money and arms to support Irish independence, just three months after the Easter Rebellion in Ireland, a bloody strike on San Francisco's waterfront had killed a man and left dozens injured only a month earlier. At 2:06 pm, as marchers were entering Market Street from Steuart, a bomb exploded, killing ten and critically injuring 40 more.

A militant San Francisco labor leader, Tom Mooney, his wife Rena, a radical worker named Warren K. Billings, and two others were soon charged with the crime. Then District Attorney Charles Fickert had been elected in 1909 with a secret fund of $100,000 put up by United Railroads, a company formed in 1903 when Patrick Calhoun bought up most of the city's streetcar lines and merged them into one company. One of DA Fickert's first acts was the dismissal of corruption charges pending against Calhoun, his chief counsel and his chief assistant, thereby ending the famous graft trials which had brought down political boss Abe Ruef and previous Mayor Schmitz.

Tom Mooney had real evidence of his innocence, but was denied a new trial or pardon for 22 years. At 2:01 p.m. on July 22, 1916, a photo by Wade Hamilton places Tom and Rena Mooney on the Eilers Buildng at 975 Market, at the time they were allegedly placing the bomb a mile east at Steuart and Market. This photograph was in the possession of the prosecutors but was never presented at trial.

Photo: courtesy Bancroft Library

Mooney had been a major actor in numerous strikes and organizing campaigns. By the end of 1915 he'd become a thorn in the side of the San Francisco Labor Council as much as the Chamber of Commerce with his radical calls for industrial unionism; Pacific Gas & Electric and its then subsidiaries (San Joaquin Light & Power Co., Western Electric Co., Sierra & SF Power Co.) considered him a dangerous foe after a big strike from May 1913 through January 1914.

1908 photo of radicals, including Tom Mooney, 2nd from right, and Socialist Presidential candidate Eugene Debs, third from right.

Photo: provenance unknown

In late 1915, Mooney had targeted the anti-union United Railroads for organizing. In 1916, California had two major cities, San Francisco and Los Angeles, the former known as the most unionized city in America, the latter as a bastion of conservatism and the most open shop (i.e. non-union) city in the country. San Francisco's Chamber of Commerce keenly felt the difference, as new investment was mostly heading south to Los Angeles and the land of cheap, abundant labor.

Between June 9, 1916 and July 17, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce claimed that 38 "non-union workers" [scabs] were sent to the hospital because of attacks by striking longshoremen. Two strikers were dead. In this violent atmosphere the Chamber issued its first public endorsement of the open shop on June 22, 1916. On July 10, a meeting of over 2,000 merchants packed the floor of the Merchant's Exchange and endorsed the creation of a standing "Law and Order Committee" of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce to "rid San Francisco of anarchistic elements." By year-end the Law and Order Committee had a fund at its disposal of $1 million.

Behind the scenes was one Martin Swanson, a detective with a long involvement in strikes, and various labor confrontations in San Francisco, mostly working for PG&E, the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Co. (later PacBell), and other utilities and railroads. Swanson had spent a couple of months trying to frame Mooney for a bombing of PG&E power lines just south of San Francisco on San Bruno mountain, offering bribes of $5,000 to several of Mooney's allies. He also maintained constant surveillance and harassment of Mooney, Billings, and the anarchists Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman, who were living at 569 Dolores in the Mission District.

One of the many efforts to publicize the Mooney case, this one in 1929.

Tom Mooney in his cell in San Quentin (c. 1932)

Image: Bancroft Library

Agitational writing in 1938 that successful led to Mooney's pardon in 1939 by new Governor Culbert Olson.

After the Preparedness Day bombing, Swanson was appointed as investigator for the (clearly corrupt) District Attorney that same evening. Over the next two years it was gradually revealed that Martin Swanson was the man primarily responsible for finding and coaching false witnesses against Mooney and Billings. Tom Mooney was tried first, and based on the false evidence, convicted of first degree murder and given the death sentence. Some time later Warren Billings was tried, and though some of the testimony had already been discredited, he too was convicted of first degree murder but given a life sentence. The three other alleged co-conspirators were tried later and all acquitted as the fraudulent case against them had collapsed by then.

Mooney had his death sentence commuted to life in prison by California's governor under pressure from President Woodrow Wilson in 1917. It took another 22 and a half years before Tom Mooney was granted an unconditional pardon by newly-elected liberal Democratic governor Culbert Olson in January, 1939. Warren Billings would receive his release from prison in 1942.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/ssfMOONEDT1" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Mooney appeals for his release in 1933 (video)

READ MORE:

Frame-up by Curt Gentry, © 1967, WW Norton & Co., New York.

Life of an Anarchist: The Alexander Berkman Reader, ed. Gene Fellner, Four Walls Eight Windows, New York: 1992.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/chamber-of-commerce-preparedness-day-film-llsf-2015-20151208-30p-7-mbps" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Chamber of Commerce propaganda film to warn population.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/tom-mooney-returns-1939-llsf-2016-20-mbps-1" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Footage of Tom Mooney on his long-awaited return to San Francisco after 22.5 years in jail for a bombing in 1916 he had nothing to do with. He was pardoned by new governor Culbert Olson and made his way back to SF's Ferry Building where he was greeted by 10,000 people. The city accompanied him on his walk up Market to the Civic Center and this footage was shot near the end of the parade.

Video: from "Lost Landscapes 11, 2016" edited by Rick Prelinger, courtesy Prelinger Archives