Greyhound Bus Strike 1983: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' ''by Chris Fillmer, originally published in the magazine ''Ideas & Action'' in 1984.'' Image:Greyhound-Strike-1983-mass-picketing-on-7th-street-IMG00073.jpg '''Mass picketing on 7th Street outside of the Greyhound Bus Terminal between Mission and Stevenson Alley, November 1983.''' ''All photos: Chris Carlsson'' Image:Greyhound-bus-during-1983-strike-IMG00072...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | ||

''by Chris Fillmer, originally published in the magazine ''Ideas & Action'' | ''by Chris Fillmer, originally published in the magazine ''Ideas & Action,'' Spring 1984.'' | ||

[[Image:Greyhound-Strike-1983-mass-picketing-on-7th-street-IMG00073.jpg]] | [[Image:Greyhound-Strike-1983-mass-picketing-on-7th-street-IMG00073.jpg]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:41, 18 December 2023

Historical Essay

by Chris Fillmer, originally published in the magazine Ideas & Action, Spring 1984.

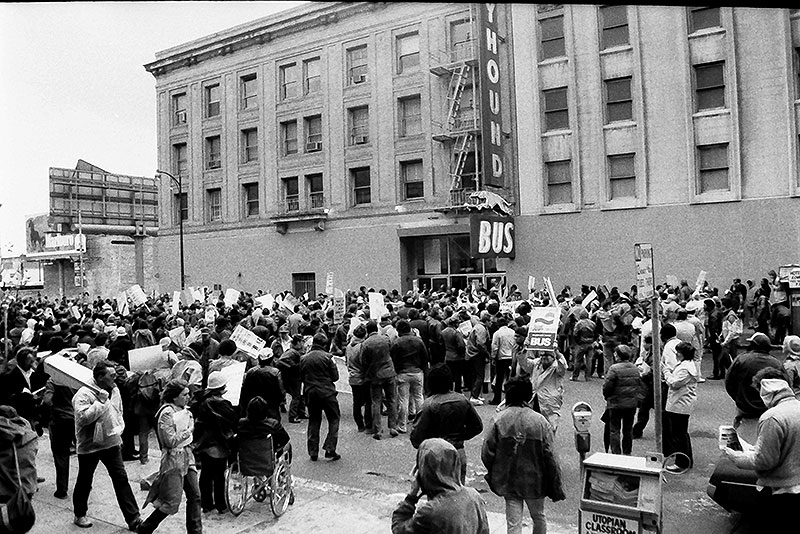

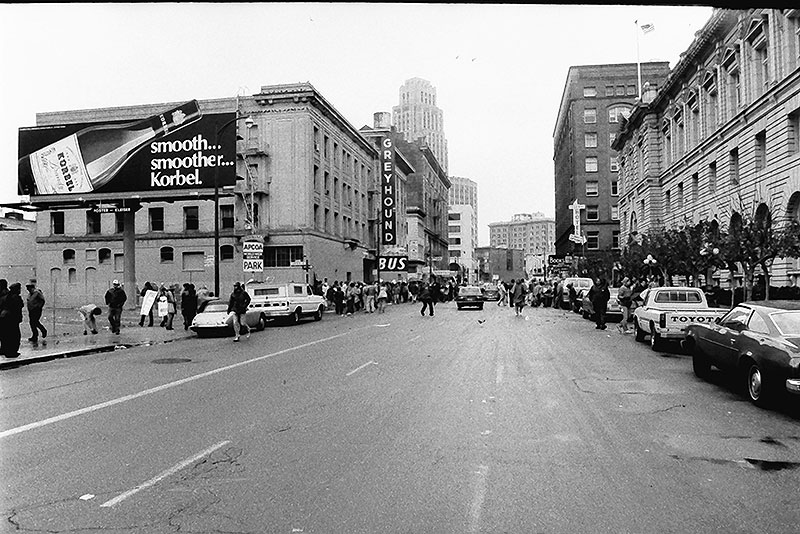

Mass picketing on 7th Street outside of the Greyhound Bus Terminal between Mission and Stevenson Alley, November 1983.

All photos: Chris Carlsson

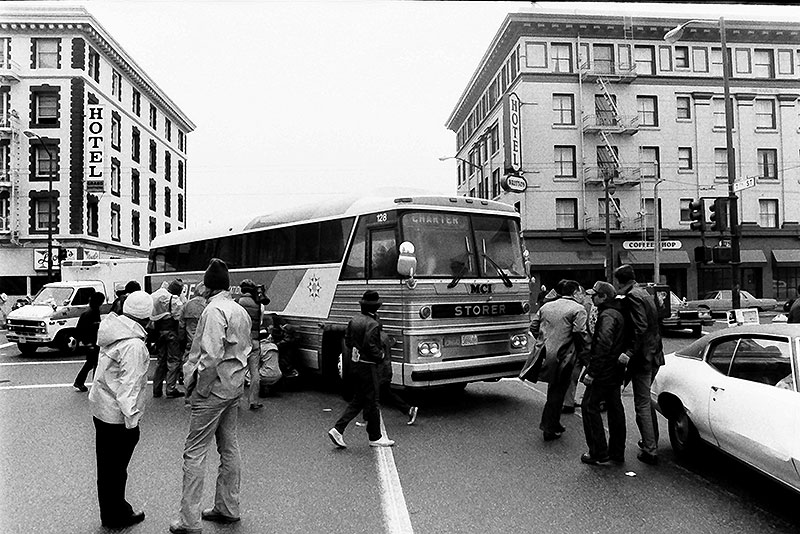

Passengers disembarking a block away from the terminal due to the pickets blocking entry.

On Dec. 19, 1983, 74% of the Greyhound Bus Lines employees who belong to the Amalgamated Transit Union voted to accept a contract with Greyhound that amounted to a 15% wage/benefit cut overall. Not only were outstanding issues such as safety problems and abuse of casual or "extra-board" drivers not dealt with, the workers took a direct 7.8% pay cut along with the Ioss of four to five paid vacation days; also, the company will no longer cover the complete cost of health insurance or pensions.

One of the biggest losses was one not voted for: On Dec.5th, Ray Phillips, of ATU Cleveland Local 1043, was run down and killed outside Zanesville, Ohio by a scab trainee-driver. The trainee was reportedly egged-on by his instructor. The bus drove through union pickets in a crosswalk, running against a traffic signal in doing so. Ray Phillips was unable to get out of the way. The slave driving the bus, as well as the slave-driving person in charge, went unpunished by the law. On the other hand, outside many a Greyhound depot the cops beat heads during the course of the strike. And about 30 strikers have been fired by Greyhound under allegations of causing "personal injury or property damage."

This may be the contract, but it ain't justice!

Greyhound Lines had opened bargaining with the ATU negotiators long before the actual strike by offering what amounted to a 25-30% cut in wages and benefits. As justification for its position, Greyhound cited the growing number of take-away contracts and non-union operators in the bus and air transportation industry. If the ATU membership didn't accept this offer the Greyhound Corporation (the conglomerate that owns the bus lines as well as businesses in other industries) claimed it would be forced to shut down the Bus Lines division within three years due to the increased competition.

This first offer was rejected by the Greyhound workers with 94% voting "No." It was so bad that even the official union negotiators urged a "No" vote. And why should they have accepted it? Pickets from San Francisco Local 1225 knew quite well that the Greyhound Corporation earned $103 million in profits through mid-November in 1983. As Labor Notes pointed out (Nov. 22, 1983), "Greyhound Lines Chair Frank Nagotte pulled down a hefty $447,000 in salary and benefits" in 1983. In general, Greyhound management was slated to receive a 7-10% salary/benefit increase. Despite the competition from lower air fares, cited by Greyhound management, the Bus Lines division alone earned a profit that has been estimated at $5 million in the first nine months of 1983. Neither the parent conglomerate nor the Bus Lines division were in any immediate danger of bankruptcy, unlike the situation of Chrysler in 1980 or Continental in early 1983.

After Greyhound's first contract of fer was voted down, the ATU negotiators came back with the offer to leave the then-valid contract in effect. Not a hint that even the current contract left important matters untouched. But Greyhound was out for blood, and they were in no mood to accept the status quo. Thus, the company just repeated their demands for concessions.

The union piecards then pleaded for binding arbitration -- anythmg to avoid a strike!

After the strike got underway, the stalemate in negotiations lasted until the Bus Lines tried to run scab buses, beginning on Nov. 17th.

In response, the striking Greyhound workers carried out militant actions that were effective as far as they went. For example, early in the morning on Nov. 17th pickets from Local 1225 in San Francisco, together with some supporters, tried to block the departure of buses from the 7th Street depot in downtown San Francisco. There was then a cop attack on the picket line and a melee ensued. Only one bus left the station. It soon experienced a collision with another vehicle (the driver of the other vehicle just happened to be a striking Greyhound driver) and it was forced to retreat to the S.F. depot.

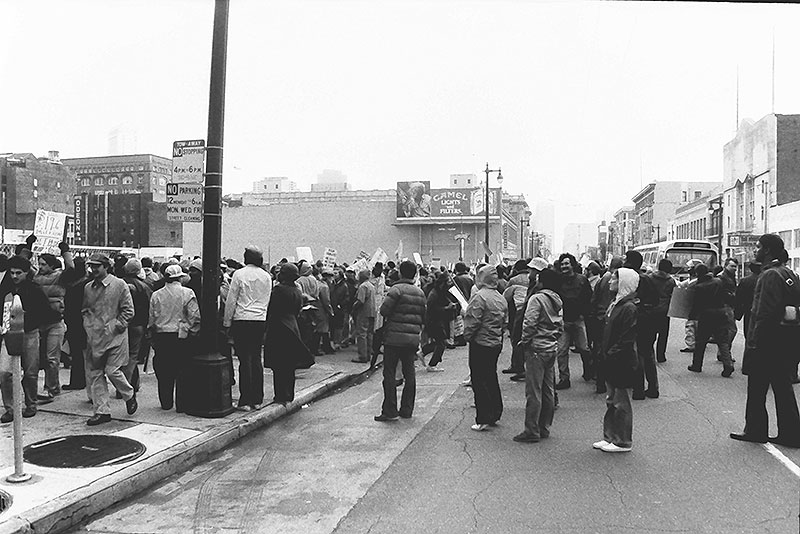

Greyhound bus blockaded on 7th and Mission, November 17, 1983.

Outside the main doors on 7th Street.

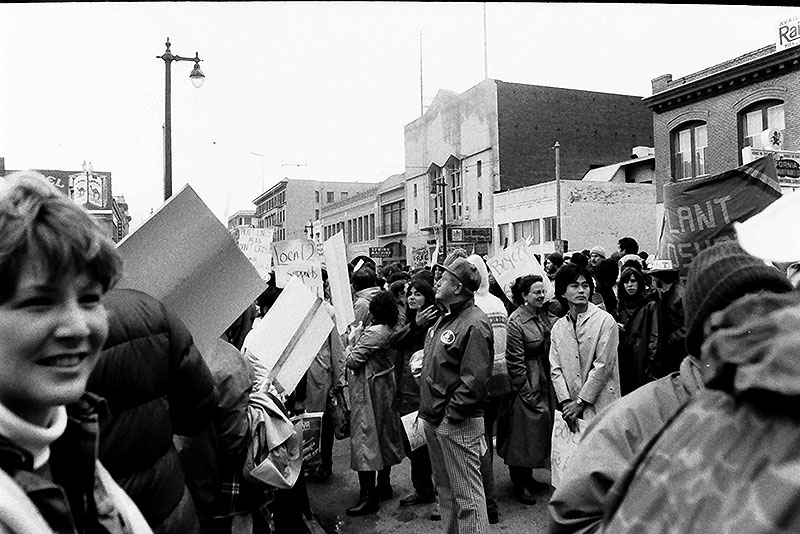

Blockading the main bus entrance along Mission Street.

On Mission Street looking northeast, Grant Building visible in background.

When two of us arrived at the picket line later that afternoon, all of the men and women we talked to told us they were opposed to any give-backs. The involvement and mutual support shown by the local 1225 members was reflected in the fact that this local had organized rank-and-file-elected strike committees.

The various actions around the country ran the gamut from (some times wild) picketing, support rallies with people from other unions and leftists to vandalism. All of this added up to a fairly successful effort to disrupt scab operations. Out of 1200 members in Local 1225 in the Bay Area, only one person crossed the picket line, and Local 1500 in Memphis had only three scabs out of its 300 members. After a month of trying, the Bus Lines was only able to get about 10% of its system running and often the buses ran empty or with few riders.

The ranks shut down the bus lines effectively enough that they were able to halt the company's effort to break the labor organization in the Bus Lines Division and ultimately forced them to modify their stance a little (though not much).

And yet, in the midst of this strike activity, the drivers, ticket agents, baggage handlers and mechanics of the Council of Greyhound ATU Locals voted to accept a crummy take-away contract, with 74% voting "Yes." Why?

One reason is that the official union negotiators sent out the contract offer to be voted on by each ATU member in the privacy of their own home, where he or she is most likely to read it in isolation from their fellow workers—the best way to encourage a feeling that you're just a powerless individual and can't fight city hall.

During any strike—especially in a situation where union bureaucrats control dues-funded strike pay-material pressures (rent or house payments, utility bills, RV financing, etc.) may influence strikers' decisions, as it did some ATUers after seven weeks on strike. One San Francisco striker told us that he had started saving as soon as he heard the company's first offer. He didn't want to be starved into accepting such a contract, he said. But what of the members who couldn't save, trying to enjoy a rather moderate style of life?

Since Greyhound is not merely a bus line, but a conglomerate with revenues from many lines of business, it's capacity to bear losses from a strike is much greater than that of individual strikers and any dependents to bear the loss of wages. Even those who have substantial savings may run short during a long strike.

Despite their diplomatic relations with the leaders of the other organized labor forces in the U.S., the ATU leaders never called upon other unions or workers to engage in secondary strike activity that might have aided the Greyhound strike—such as sympathy strikes in the transport sector. "Why, that's against the law!" How convenient. In fact, the ATU leadership didn't even bother to make minimal "No concessions" demands.

The basic problem isn't really bad leadership

The analyses of the Greyhound strike by various "friends of labor," "vanguards of the workers" or "tribunes of the people" that I have read try to explain why give-backs ultimatelv prevailed at Greyhound by referring to union bureaucrats, politicians—everything but the free-thinking and decision-making of the rank-and-file. Here are a few examples:

- Greyhound Corporation, . . . the Reagan administration and capitulating top union leadership. . . forced the 12,700 Bus Lines unionists to take pay cuts and other weakening contractual clauses.

- —People's World (12/24/84)

- As a result of the combined pressure of Greyhound management and the labor bureaucracy. . . of their own union and the AFL-CIO as a whole [they] concluded that they had no choice other than to vote if up.

- —Torch (12/83)

- What's behind the defeats of the unions (UE, PATCO, USWA, IAM, CWA, ATU) is not so much the courts and the cops, but the failure of the union misleaders to unleash the enormous power of labor solidarity.

- —Workers Vanguard (11/18/83)

These statements do contain some truth in that it is certainly true that the ATU or AFL-CIO officials didn't facilitate any actions which might have led to fighting off any give-backs.

Actually, I'm not surprised. Business unions have always acted in this manner. Whenever matters have gotten blunt, they have proven quite bluntly that they are representing the interests of their members only within the narrow framework of profitability of one particular industry in one particular nation, despite the global and integrated character of the system. At the least ATU or AFL-CIO leadership are not misrepresenting themselves. Business unionism IS basically pro-capitalist—it accepts the existence of private profit and ruling class power as a fact that can't be challenged They are the guardians of the contracts that regulate the position of workers within this framework and act as simply mediators between wage-earners and the corporate few at the top who use our labor. As such, they are not particularly interested in facilitating militant democratic control in working class organizations and activity. What need would there be for "mediators" if decision-making and responsibility in the struggle rested squarely where it belongs: in the hands of those directly affected by the outcome. In fact, the union officialdom will fail to support strikes, repress wildcats, squelch dissent and ignore their members grievances if it is necessary to preserve the existing framework.

Yet despite the non-facilitation and hindrances, and their pitiful business union perspective, this is not the same thing as "force," a "failure to unleash" or "leaving no choice." The fact that the ranks acted within the framework of business unionism -- with all its limitations—involved an element of choice.

The ranks could have acted on their full knowledge and prepared better in advance. Knowing what they know about the Greyhound Corporation and the Amalgamated Transit Union, Greyhound workers had two primary possibilities: They either had to convince the union and non-union workers of the other parts of the Greyhound Corporation to engage in some joint struggle with them, or else they could try to convince other transport workers and their unions to come out in sympathy with them. Only by generalizing the struggle in this way could the ATU have created enough pressure to win even their minimal demands of "No concessions."

But of course, all that's illegal under existing contracts and laws and union bureaucrats are very law-abiding. They would never sanction such a thing. But that only means that the ranks needed to take matters into their own hands from the very beginning. The rank and file did not have to respect either the bureaucrats or the law. There is the example of the rank-and-file-elected strike committees set up by the Bay Area unionists of Local 1225. This showed an awareness of the need to not leave things to the top officials and their appointed staffs, even in a strike limited to Greyhound Bus Lines.

Unionists who were already aware of the value of rank-and-file-run strike committees could have argued loud and clear for such committees being formed throughout the union—especially in a situation that called for actions that would go beyond the boundaries of what would be acceptable to the union tops. While building rank-and-file solidarity and democracy within the ATU, such committees could have reached out to workers in other divisions of the Greyhound conglomerate and other transport unions and rank-and-filers. Rank-and-filers could have set the stage for getting support by giving support to these other groups of workers on those occasions when it is needed (e.g., by giving money, picket-line presence, staunch opposition to strike-breaking, etc.). Instead of a situation where workers are separated into many different unions that are limited to just the concerns of workers in one particular company or industry, or separated into those who do belong to unions and those who don't, what we need is mutual support.

Competition and lack of support can only undermine all of us; what's needed is put into practice in our workplaces and struggles the principle, "We'd better all hang together or we'll each hang separately. "

None of these "could be's" are too unrealistic. And yet, the "could be's" remained just that. I believe that ultimately the failure of the ranks to pursue adequate means for even minimum ends rests upon their current acceptance of the prevailing economic and political system. With no perspectives for creating a different type of society, based on equality and freedom, most rank-and-filers fell into the self-defeating attitude encapsulated in the phrase, "give a little now or lose it all later. "

The corporation referred to its freedom under "free enterprise" when it threatened to close down the Bus Lines if it was "forced" to by lower profits or future losses-or in effect, whenever they want to. When so many assume there can be no alternative to capitalist power, the rank and file can be intimidated and frightened. And in the end, many workers may give a little now and lose it all later. But unless we go along with it, there is nothing that says the corporate few must be allowed to get away with that kind of arbitrary power. In fact, the threat of a shutdown could be met with occupations of company property, sympathy strikes from other Greyhound divisions or other transport workers, or even a general strike, if the solidarity has been developed.

What is needed is to break the cycle of futile acceptance, unhappy submission. And it can be done. Our abilities are many; our potential is great. The self-organization that we need to create today—directly democratic local worker meetings and rank-and-file committees, federated together throughout regions and industries and built independently of the union bureaucracies (where such bureaucracies exist)—is at times visible before us -- as some people make such organization happen from time to time in various lands.

Such autonomous organization needs to be seen as the the basis of a new society of cooperative and non-discriminatory workers' self-management. Unless this larger possibility is recognized, we will never be in a position to resolve the full range of human problems and accomplish our goals, whether in one industry or in the entire society. This needs no Vanguard Party, no Labor Party—in fact no "Party" at all. It requires the development of a social movement based upon direct democracy, direct action and individual responsibility, liberty and pride.

And you can still go out dancing!

View north on 7th Street from Mission. Greyhound Terminal was torn down in the late 1990s and replaced in the early 21st century by a new Federal Building.