Joe Jachetta's Story: Difference between revisions

m (1 revision(s)) |

No edit summary |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

''by Audrey Tomaselli'' | |||

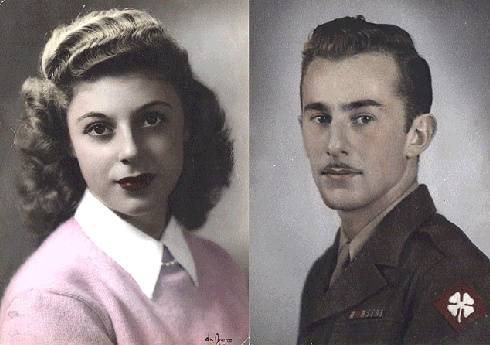

Joe Jachetta | [[Image:italian1$lucy-and-joe-jachetta.jpg]] | ||

'''Joe and Lucy Jachetta right after World War II.''' | |||

''Jachetta family photos courtesy Joe Jachetta'' | |||

[[Image:Italian1$joe-jachetta$mother itm$jachetta s-mother-during-wwii.jpg]] | |||

'''Joe Jachetta's Mother, Amelia Gallo, during World War II''' | |||

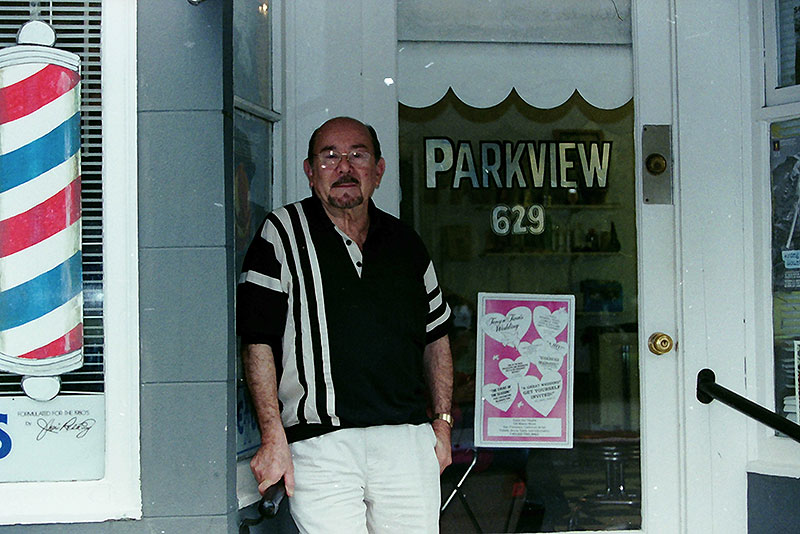

Joe | [[Image:Joe-Jachetta-CU IMG00045.jpg]] | ||

Joe | '''Joe Jachetta in front of his salon in late 1999.''' | ||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | |||

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/JoeJachettaOnNorthBeachLifeBeforeRefrigerators" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | |||

''North Beach hair stylist Joe Jachetta, interviewed by Audrey Tomaselli of the Telegraph Hill Dwellers oral history project, talks about how folks in his building kept things cold before refrigerators.'' | |||

Joe was with | Joe Jachetta was born 75 years ago at 334 Vallejo Street on the eastern slope of Telegraph Hill. His personal history is entwined with that of our neighborhood's. Joe's maternal grandfather, Giacomino Gallo, came to this country in 1886 and worked as a waiter at Fior d'Italia's original location on Broadway at Kearny. In fact, Joe's mother, Amelia Gallo, was born in the room above the restaurant. After learning the business, Giacomino (in partnership with his sister and her husband) opened a restaurant and boarding house a few blocks away on Front Street. Joe said, "I remember my mother describing a free lunch. Imagine going into this bar and all the cold cuts were free! A 1906 earthquake story was told more than once in our family: The earthquake hit when everyone was asleep. My mother, age 6, was in a room where a big chifforobe had fallen in front of the door. One of the tenants in the boarding house was a big, burly man who worked on a barge, and this man pushed the door open and carried my mother down the stairs (which were all crooked). He herded her and her family down to the waterfront and they all got on this barge which went out and anchored in the middle of the Bay and they watched the City burn." | ||

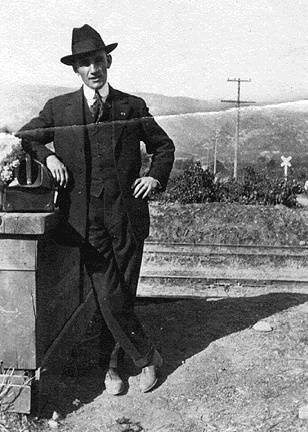

[[Image:italian1$joe-jachetta$gallo_itm$jachetta_s-grandfather.jpg]] | |||

'''Joe Jachetta's grandfather, Giocomino Gallo, posing in North Beach, 1890s.''' | |||

Joe was only 7 years old when his grandfather, Giacomino, died; but he has a few fond memories of him. He remembers Nonno sitting at the head of the table, reaching down to the wine jug on the floor beside him and hoisting it over his shoulder to refill the glasses. Each year, even during the Depression, his family made 200 gallons of wine. "I remember in our basement there was never less than a thousand bottles of wine---aging just right. I can smell the wine being made with these gigantic presses. They just went round and round and strained it until they got every drop. For fun, we used to take turns stomping the grapes. The container was pretty big; you needed a ladder to get into it. The truck would stop in front of the house with these lugs of grapes. The driver would put one box on the pavement, so the kids could come around and help themselves. Otherwise we'd be running back and forth stealing grapes from the truck. When a truckload of grapes came into the neighborhood, there would be something like a telegraph system. Someone would yell 'fugi'. It was amazing! It would go from one to the other, around the block and up the hill and before you knew it all the kids in the neighborhood were there. That's what the box on the ground was for." There were six flats at 334 Vallejo and all the families in the building shared the equipment and helped each other with the wine making. | |||

Joe recalled the easy way neighbors related to one another. "It was a working class building and quite often people would come down the back stairs and instead of going down into the basement to get out to the front of the house, they would just walk through my mother's flat. I remember in the evening sitting there having dinner and people walking through to get out to the front of the house. Nobody cared. It was just, 'Hi, how are you? I'm going out on a date.' We were on the first floor and it was easier to just walk through Amelia's house. We had the only telephone in the building. Everybody would use that phone. All six flats. We would be having dinner and there would be somebody phoning for a doctor. Our family also had a radio; people next door or two houses away came over to listen to the radio. After dinner, I would jump the fence from my backyard into the next backyard, run up the stairs, and there would be the Dinelli family. And I would walk right into their kitchen, then go into another room and wait till they finished having dinner and then they'd come in and we'd play Monopoly. Talk about the good old days; that was a wonderful feeling." | |||

[[Image:Italian1$joe-jachetta$restaurant itm$front-street-saloon-outside.jpg]] | |||

''' | '''Jachetta family restaurant/boarding house exterior view.''' | ||

[[Image:Italian1$joe-jachetta$restaurant itm$front-street-saloon-inside.jpg]] | |||

'''The family restaurant and boarding house on Front Street.''' | |||

Prescott Alley across the street from his house provided Joe with a short cut right to the back door of the (then) Washington Irving grade school on Broadway between Sansome and Montgomery. Joe went on to attend Francisco Middle School and Galileo High School. He and his friends often stopped at Athens Ice Cream Parlor (which was located on Columbus between Union and Green) on the way home. Joe describes it as "having booths and a marble-topped counter and sodas--lemon coke, chocolate coke, cherry coke. They had fabulous sundaes; one was called the Golden Gate Bridge which had nine scoops of ice cream and chocolate syrup and whipped cream. It was the most expensive thing you could buy; I think it was 30 cents." | |||

On Sundays Joe was an altar boy and served mass at St. Francis Church on Vallejo Street. In his teens he became a sextant and recalls having to change the light bulbs in the row of lights going down the center of the ceiling. "Around each fixture there is a lot of space and I used to climb up into the steeple and over the top of that row of lights and lie flat and look down and I could see the top of everyone's head during the service! I know St. Francis Church, every door, every corner; I know places nobody knows. Next time you're in there look up at those light fixtures!" | |||

' | When he was 19 Joe was drafted for service in the Second World War. On New Year's Eve 1944, he was among the American troops sent in landing barges to the beaches of France as the Allied invasion began. The first man to have disembarked from his barge, Joe stepped off into water that was over his head. When he surfaced, his backpack was gone. It contained his ID and personal effects which included a loved photograph of Lucy Accurso, a girl he had met in his first year at San Francisco Junior College. It was the coldest January on record in France. They marched in their wet clothes to what had been a convent where they were billeted. Miraculously, the next morning, his backpack washed up on the beach and was retrieved by one of the guards on duty. Joe remembers opening the pack and finding Lucy's picture intact and hanging it up to dry. | ||

Because of his experience here at St. Francis Church, the Catholic chaplain often asked Joe to assist whenever they were able to hold mass at the front. One of his platoon mates, Zeke, dubbed him Holy Joe. Not long after landing in France, they had set up operations in an old farmhouse when bombs started to hit. They ran for cover to the basement and Joe took out his rosary and prayed silently. Meanwhile, Zeke went to pieces as the farmhouse collapsed around their ears. Zeke later commented to him about that---how Joe had been calm and quiet because he had something to believe in. Zeke continued to call him Holy Joe, but it had a different tone and meaning after that. During that attack Joe again lost his backpack, but three days later he went back and picked through the rubble and found it (with Lucy's picture, of course). Joe still has that photo. | |||

Joe | Joe was with General Patton's division when they liberated Dachau. | ||

Joe was not wounded during the War (although he weighed only 102 pounds when he was discharged), but he came home with emotional scars---what we now know as post traumatic stress syndrome. For years afterward he suffered from horrific nightmares. Meeting this dapper, cheerful, vigorous man today, it's hard to believe he has endured so much. He has a twinkle in his eye when he talks about how he proposed to Lucy upon his return to San Francisco in 1945. It was in a night club on Bay and Columbus called La Fiesta, and that night they had won a rhumba contest. "You see, Lucy and I were truly, truly meant for each other. I had to have this lady with that smile and those two dimples." Joe delights in recounting that, prior to La Fiesta nightclub, the building was occupied by Jachetta Brothers Body and Fender Shop. "My father was the mechanic and my uncle was the body repair man. When my uncle got married and moved to Healdsburg, they decided to go out of business --- one of the pride things was they did not go bankrupt, they just went out of business --- that was a big thing." | |||

' | After they were married, Lucy and Joe found a wonderful apartment two buildings away from his mother's house. "Someone had added a floor to this house so it was like a little penthouse. We had four rooms and fourteen windows and they all overlooked the Bay and the bridge and Treasure Island and everything. That was a fun time. For less than a thousand dollars we outfitted the whole four room apartment including the dining room set, a sofa, a bed and mattress, and a washing machine. We paid twenty-five dollars a month in rent, with an additional five dollars in cash under the table." | ||

In 1948, after having worked as a hairdresser at the Emporium for a couple of years, Joe borrowed $5,000 from his uncle and opened the Parkview Salon in the Palace Theater building on Powell Street across from Washington Square. "My mother was a fixture at St. Francis Church, so many of my first customers were from the Catholic Ladies' Aid. A friend became my partner and we paid off the debt in six months. We were partners for 34 years." In 1958 Joe moved the business to the southwest corner of Union and Powell where it remained for another 30 years. Ten years ago the salon moved again to its present location on Union between Stockton and Columbus. "Some of my customers have been coming to me for 50 years. And I haven't burned out because I enjoy center stage. I enjoy what I do!" | |||

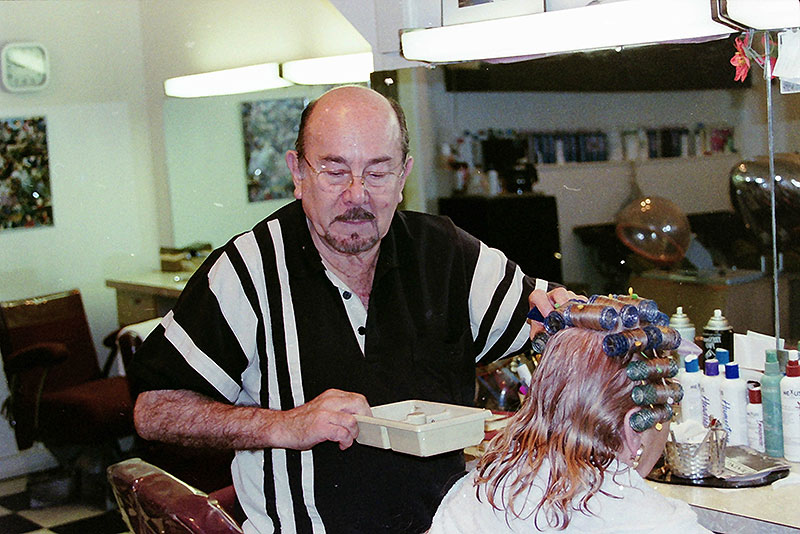

[[Image:Joe-Jachetta-doing-hair IMG00044.jpg]] | |||

'''Joe at his Parkview Salon, November 1999.''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | |||

Lucy and Joe have six children and twelve grandchildren. To his great delight all of them gathered at his home last summer to celebrate Fathers' Day. At the end of the interview, Joe surveyed his lovely home and garden and said, "It's hard to believe all this came from one little beauty shop on Washington Square." | |||

'''[http://www.thd.org TELEGRAPH HILL DWELLERS ORAL HISTORY SERIES]''' | |||

[[North Beach: Little Italy | Prev. Document]] [[Tina Modotti | Next Document]] | |||

[[North Beach: | [[category:Italian]] [[category:North Beach]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:1990s]] [[category:1890s]] [[category:Oral Histories]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:52, 18 December 2023

Historical Essay

by Audrey Tomaselli

Joe and Lucy Jachetta right after World War II.

Jachetta family photos courtesy Joe Jachetta

Joe Jachetta's Mother, Amelia Gallo, during World War II

Joe Jachetta in front of his salon in late 1999.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/JoeJachettaOnNorthBeachLifeBeforeRefrigerators" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

North Beach hair stylist Joe Jachetta, interviewed by Audrey Tomaselli of the Telegraph Hill Dwellers oral history project, talks about how folks in his building kept things cold before refrigerators.

Joe Jachetta was born 75 years ago at 334 Vallejo Street on the eastern slope of Telegraph Hill. His personal history is entwined with that of our neighborhood's. Joe's maternal grandfather, Giacomino Gallo, came to this country in 1886 and worked as a waiter at Fior d'Italia's original location on Broadway at Kearny. In fact, Joe's mother, Amelia Gallo, was born in the room above the restaurant. After learning the business, Giacomino (in partnership with his sister and her husband) opened a restaurant and boarding house a few blocks away on Front Street. Joe said, "I remember my mother describing a free lunch. Imagine going into this bar and all the cold cuts were free! A 1906 earthquake story was told more than once in our family: The earthquake hit when everyone was asleep. My mother, age 6, was in a room where a big chifforobe had fallen in front of the door. One of the tenants in the boarding house was a big, burly man who worked on a barge, and this man pushed the door open and carried my mother down the stairs (which were all crooked). He herded her and her family down to the waterfront and they all got on this barge which went out and anchored in the middle of the Bay and they watched the City burn."

Joe Jachetta's grandfather, Giocomino Gallo, posing in North Beach, 1890s.

Joe was only 7 years old when his grandfather, Giacomino, died; but he has a few fond memories of him. He remembers Nonno sitting at the head of the table, reaching down to the wine jug on the floor beside him and hoisting it over his shoulder to refill the glasses. Each year, even during the Depression, his family made 200 gallons of wine. "I remember in our basement there was never less than a thousand bottles of wine---aging just right. I can smell the wine being made with these gigantic presses. They just went round and round and strained it until they got every drop. For fun, we used to take turns stomping the grapes. The container was pretty big; you needed a ladder to get into it. The truck would stop in front of the house with these lugs of grapes. The driver would put one box on the pavement, so the kids could come around and help themselves. Otherwise we'd be running back and forth stealing grapes from the truck. When a truckload of grapes came into the neighborhood, there would be something like a telegraph system. Someone would yell 'fugi'. It was amazing! It would go from one to the other, around the block and up the hill and before you knew it all the kids in the neighborhood were there. That's what the box on the ground was for." There were six flats at 334 Vallejo and all the families in the building shared the equipment and helped each other with the wine making.

Joe recalled the easy way neighbors related to one another. "It was a working class building and quite often people would come down the back stairs and instead of going down into the basement to get out to the front of the house, they would just walk through my mother's flat. I remember in the evening sitting there having dinner and people walking through to get out to the front of the house. Nobody cared. It was just, 'Hi, how are you? I'm going out on a date.' We were on the first floor and it was easier to just walk through Amelia's house. We had the only telephone in the building. Everybody would use that phone. All six flats. We would be having dinner and there would be somebody phoning for a doctor. Our family also had a radio; people next door or two houses away came over to listen to the radio. After dinner, I would jump the fence from my backyard into the next backyard, run up the stairs, and there would be the Dinelli family. And I would walk right into their kitchen, then go into another room and wait till they finished having dinner and then they'd come in and we'd play Monopoly. Talk about the good old days; that was a wonderful feeling."

Jachetta family restaurant/boarding house exterior view.

The family restaurant and boarding house on Front Street.

Prescott Alley across the street from his house provided Joe with a short cut right to the back door of the (then) Washington Irving grade school on Broadway between Sansome and Montgomery. Joe went on to attend Francisco Middle School and Galileo High School. He and his friends often stopped at Athens Ice Cream Parlor (which was located on Columbus between Union and Green) on the way home. Joe describes it as "having booths and a marble-topped counter and sodas--lemon coke, chocolate coke, cherry coke. They had fabulous sundaes; one was called the Golden Gate Bridge which had nine scoops of ice cream and chocolate syrup and whipped cream. It was the most expensive thing you could buy; I think it was 30 cents."

On Sundays Joe was an altar boy and served mass at St. Francis Church on Vallejo Street. In his teens he became a sextant and recalls having to change the light bulbs in the row of lights going down the center of the ceiling. "Around each fixture there is a lot of space and I used to climb up into the steeple and over the top of that row of lights and lie flat and look down and I could see the top of everyone's head during the service! I know St. Francis Church, every door, every corner; I know places nobody knows. Next time you're in there look up at those light fixtures!"

When he was 19 Joe was drafted for service in the Second World War. On New Year's Eve 1944, he was among the American troops sent in landing barges to the beaches of France as the Allied invasion began. The first man to have disembarked from his barge, Joe stepped off into water that was over his head. When he surfaced, his backpack was gone. It contained his ID and personal effects which included a loved photograph of Lucy Accurso, a girl he had met in his first year at San Francisco Junior College. It was the coldest January on record in France. They marched in their wet clothes to what had been a convent where they were billeted. Miraculously, the next morning, his backpack washed up on the beach and was retrieved by one of the guards on duty. Joe remembers opening the pack and finding Lucy's picture intact and hanging it up to dry.

Because of his experience here at St. Francis Church, the Catholic chaplain often asked Joe to assist whenever they were able to hold mass at the front. One of his platoon mates, Zeke, dubbed him Holy Joe. Not long after landing in France, they had set up operations in an old farmhouse when bombs started to hit. They ran for cover to the basement and Joe took out his rosary and prayed silently. Meanwhile, Zeke went to pieces as the farmhouse collapsed around their ears. Zeke later commented to him about that---how Joe had been calm and quiet because he had something to believe in. Zeke continued to call him Holy Joe, but it had a different tone and meaning after that. During that attack Joe again lost his backpack, but three days later he went back and picked through the rubble and found it (with Lucy's picture, of course). Joe still has that photo.

Joe was with General Patton's division when they liberated Dachau.

Joe was not wounded during the War (although he weighed only 102 pounds when he was discharged), but he came home with emotional scars---what we now know as post traumatic stress syndrome. For years afterward he suffered from horrific nightmares. Meeting this dapper, cheerful, vigorous man today, it's hard to believe he has endured so much. He has a twinkle in his eye when he talks about how he proposed to Lucy upon his return to San Francisco in 1945. It was in a night club on Bay and Columbus called La Fiesta, and that night they had won a rhumba contest. "You see, Lucy and I were truly, truly meant for each other. I had to have this lady with that smile and those two dimples." Joe delights in recounting that, prior to La Fiesta nightclub, the building was occupied by Jachetta Brothers Body and Fender Shop. "My father was the mechanic and my uncle was the body repair man. When my uncle got married and moved to Healdsburg, they decided to go out of business --- one of the pride things was they did not go bankrupt, they just went out of business --- that was a big thing."

After they were married, Lucy and Joe found a wonderful apartment two buildings away from his mother's house. "Someone had added a floor to this house so it was like a little penthouse. We had four rooms and fourteen windows and they all overlooked the Bay and the bridge and Treasure Island and everything. That was a fun time. For less than a thousand dollars we outfitted the whole four room apartment including the dining room set, a sofa, a bed and mattress, and a washing machine. We paid twenty-five dollars a month in rent, with an additional five dollars in cash under the table."

In 1948, after having worked as a hairdresser at the Emporium for a couple of years, Joe borrowed $5,000 from his uncle and opened the Parkview Salon in the Palace Theater building on Powell Street across from Washington Square. "My mother was a fixture at St. Francis Church, so many of my first customers were from the Catholic Ladies' Aid. A friend became my partner and we paid off the debt in six months. We were partners for 34 years." In 1958 Joe moved the business to the southwest corner of Union and Powell where it remained for another 30 years. Ten years ago the salon moved again to its present location on Union between Stockton and Columbus. "Some of my customers have been coming to me for 50 years. And I haven't burned out because I enjoy center stage. I enjoy what I do!"

Joe at his Parkview Salon, November 1999.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Lucy and Joe have six children and twelve grandchildren. To his great delight all of them gathered at his home last summer to celebrate Fathers' Day. At the end of the interview, Joe surveyed his lovely home and garden and said, "It's hard to believe all this came from one little beauty shop on Washington Square."