19th Century Medical Self-Help: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) (added abstract) |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

''by Dr. Joan B. Trauner, Excerpted from the version which appeared in ''California History'', Spring 1978, Vol. LVII, No. 1, courtesy of the California Historical Society'' | |||

[[Image:chinatwn$chinese-medical-clinic-1890s.jpg]] | [[Image:chinatwn$chinese-medical-clinic-1890s.jpg]] | ||

| Line 4: | Line 8: | ||

''Photo: California Historical Society'' | ''Photo: California Historical Society'' | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''In the 19th century, San Francisco city officials did not provide adequate medical services to Chinatown, which meant that residents had to band together to provide their own health care. Chinese-Americans were often discriminated against in municipal facilities and were otherwise reluctant to seek medical attention outside of Chinatown. This led to the creation of small local hospitals which, though technically illegal, were permitted by city officials.''' | |||

|} | |||

Another aspect of the story of the Chinese as medical scapegoats in San Francisco is the effect of public health policy upon the Chinese community itself. Throughout the nineteenth century, city officials were reluctant to finance any health services for the Chinese population even though Chinatown was popularly viewed as "a laboratory of infection." Early Chinese immigrants realized the necessity of banding together and providing for their own health care needs. In the 1850's they first grouped together into associations based upon loyalty to dan (family associations) or place of origin (district associations). In the 1860's, the district associations federated into the Chung Wah Kung Saw, which later became known as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, or the [[The Six Companies | Chinese Six Companies]]. During this period, each of the district associations maintained a small "hospital" in San Francisco for use by their aged or ailing members, a facility usually consisting of little more than a few bare rooms furnished with straw mats.[55] The existence of these hospitals was in direct violation of city health codes, but local officials allowed them to operate. In fact, during the leprosy scare of the 1870's, health officers ruled that lepers should be "debarred from hospital maintenance" at city expense and that "the Chinese companies should be compelled to maintain them and send them back to China."[56] Thus, from August, 1876, to October, 1878, known lepers were housed in the so-called Chinese "hospitals"; thereafter, health authorities ruled that all lepers were to be isolated in the Twenty-Sixth Street hospital. | Another aspect of the story of the Chinese as medical scapegoats in San Francisco is the effect of public health policy upon the Chinese community itself. Throughout the nineteenth century, city officials were reluctant to finance any health services for the Chinese population even though Chinatown was popularly viewed as "a laboratory of infection." Early Chinese immigrants realized the necessity of banding together and providing for their own health care needs. In the 1850's they first grouped together into associations based upon loyalty to dan (family associations) or place of origin (district associations). In the 1860's, the district associations federated into the Chung Wah Kung Saw, which later became known as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, or the [[The Six Companies | Chinese Six Companies]]. During this period, each of the district associations maintained a small "hospital" in San Francisco for use by their aged or ailing members, a facility usually consisting of little more than a few bare rooms furnished with straw mats.[55] The existence of these hospitals was in direct violation of city health codes, but local officials allowed them to operate. In fact, during the leprosy scare of the 1870's, health officers ruled that lepers should be "debarred from hospital maintenance" at city expense and that "the Chinese companies should be compelled to maintain them and send them back to China."[56] Thus, from August, 1876, to October, 1878, known lepers were housed in the so-called Chinese "hospitals"; thereafter, health authorities ruled that all lepers were to be isolated in the Twenty-Sixth Street hospital. | ||

| Line 13: | Line 21: | ||

In the nineteenth century medical care in Chinatown was largely provided by herbalists and pharmacies in the classic tradition of Chinese medicine. As late as 1900, no Chinese physicians appear to have been licensed to practice medicine in the state of California; in fact, not until 1908 was the Medical Department of the University of California in San Francisco to graduate a physician of Chinese origin.[59] Some Chinese of the merchant class did seek treatment from Caucasian physicians, usually for surgical care not available from Chinese practitioners.[60] In the I880's a few church missions in Chinatown also began offering the services of white female physicians for pediatric and obstetrical care. Throughout the nineteenth century, however, the vast majority of Chinese were unwilling to consult Caucasian doctors because, as one historian has noted, "the language barriers, the higher fees, and strange medications and methods were too much to assimilate."[61] | In the nineteenth century medical care in Chinatown was largely provided by herbalists and pharmacies in the classic tradition of Chinese medicine. As late as 1900, no Chinese physicians appear to have been licensed to practice medicine in the state of California; in fact, not until 1908 was the Medical Department of the University of California in San Francisco to graduate a physician of Chinese origin.[59] Some Chinese of the merchant class did seek treatment from Caucasian physicians, usually for surgical care not available from Chinese practitioners.[60] In the I880's a few church missions in Chinatown also began offering the services of white female physicians for pediatric and obstetrical care. Throughout the nineteenth century, however, the vast majority of Chinese were unwilling to consult Caucasian doctors because, as one historian has noted, "the language barriers, the higher fees, and strange medications and methods were too much to assimilate."[61] | ||

The reluctance on the part of the Chinese to seek medical attention outside of Chinatown accounted in part for their low admission rate to the San Francisco City and County Hospital and to the Almshouse during the last century. An examination of the statistics on admissions to the city and county hospital for the years 1870-1897 reveals that less than .1 percent of the hospital inpatients were of Chinese origin, whereas the Chinese population in the city varied from 5 to 11 percent of the total population. Statistics on admissions to the Almshouse disclose an even lower admission rate: of 14,402 admissions from 1871 to 1886, only 14 cases were of Chinese origin. | The reluctance on the part of the Chinese to seek medical attention outside of Chinatown accounted in part for their low admission rate to the San Francisco City and County Hospital and to the [[Laguna Honda Hospital|Almshouse]] during the last century. An examination of the statistics on admissions to the city and county hospital for the years 1870-1897 reveals that less than .1 percent of the hospital inpatients were of Chinese origin, whereas the Chinese population in the city varied from 5 to 11 percent of the total population. Statistics on admissions to the Almshouse disclose an even lower admission rate: of 14,402 admissions from 1871 to 1886, only 14 cases were of Chinese origin. | ||

Obviously, the low admission rate of the Chinese to municipal facilities cannot be attributed entirely to reluctance to seek Western-style care. An 1881 article in the ''San Francisco Chronicle'', headlined "No Room for Chinese: They are Denied Admission to the County Hospital," referred to a resolution of the Board of Health, adopted several years earlier, that had essentially closed City and County Hospital to Chinese patients.[62] | Obviously, the low admission rate of the Chinese to municipal facilities cannot be attributed entirely to reluctance to seek Western-style care. An 1881 article in the ''San Francisco Chronicle'', headlined "No Room for Chinese: They are Denied Admission to the County Hospital," referred to a resolution of the Board of Health, adopted several years earlier, that had essentially closed City and County Hospital to Chinese patients.[62] | ||

| Line 29: | Line 37: | ||

[[19th Century Medical Self-Help, Part II | continued]] | [[19th Century Medical Self-Help, Part II | continued]] | ||

Dr. Trauner is a research specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, Medical Center in the History of Health Science Department. | |||

[[Image:Chinatwn%24exclusion-act%24chs_itm%24ch-cover.jpg]] | |||

<font size=4>Notes</font size> | |||

55. U.S. Congress, Senate, ''Report of the Joint Special Committee to Investigate Chinese Immigration'', 44 Cong., 2 Sess., 1877, p. 646. | 55. U.S. Congress, Senate, ''Report of the Joint Special Committee to Investigate Chinese Immigration'', 44 Cong., 2 Sess., 1877, p. 646. | ||

Latest revision as of 16:43, 7 July 2024

Historical Essay

by Dr. Joan B. Trauner, Excerpted from the version which appeared in California History, Spring 1978, Vol. LVII, No. 1, courtesy of the California Historical Society

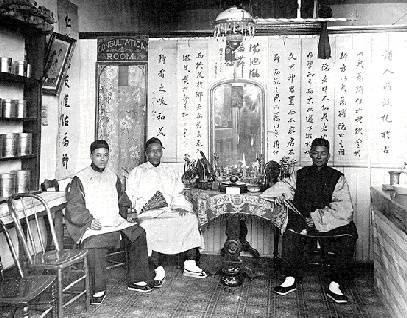

Chinese Medical Clinic in Chinatown, c. 1890s

Photo: California Historical Society

| In the 19th century, San Francisco city officials did not provide adequate medical services to Chinatown, which meant that residents had to band together to provide their own health care. Chinese-Americans were often discriminated against in municipal facilities and were otherwise reluctant to seek medical attention outside of Chinatown. This led to the creation of small local hospitals which, though technically illegal, were permitted by city officials. |

Another aspect of the story of the Chinese as medical scapegoats in San Francisco is the effect of public health policy upon the Chinese community itself. Throughout the nineteenth century, city officials were reluctant to finance any health services for the Chinese population even though Chinatown was popularly viewed as "a laboratory of infection." Early Chinese immigrants realized the necessity of banding together and providing for their own health care needs. In the 1850's they first grouped together into associations based upon loyalty to dan (family associations) or place of origin (district associations). In the 1860's, the district associations federated into the Chung Wah Kung Saw, which later became known as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, or the Chinese Six Companies. During this period, each of the district associations maintained a small "hospital" in San Francisco for use by their aged or ailing members, a facility usually consisting of little more than a few bare rooms furnished with straw mats.[55] The existence of these hospitals was in direct violation of city health codes, but local officials allowed them to operate. In fact, during the leprosy scare of the 1870's, health officers ruled that lepers should be "debarred from hospital maintenance" at city expense and that "the Chinese companies should be compelled to maintain them and send them back to China."[56] Thus, from August, 1876, to October, 1878, known lepers were housed in the so-called Chinese "hospitals"; thereafter, health authorities ruled that all lepers were to be isolated in the Twenty-Sixth Street hospital.

Not only were local authorities ambivalent about admitting Chinese patients to municipal facilities, but they also were hesitant about providing sanitary services within the Chinatown area. Dr. A. B. Stout, a prominent physician and member of the California Board of Health, testified before a congressional investigating committee in 1877 that "the city authorities undertake to clean the city in other parts, but the Chinese are left to take care of themselves and clean their own quarter at their own expense."[57]

Whenever a major epidemic threatened San Francisco, however, health officials descended upon Chinatown with a vengeance. During the smallpox epidemic of 1876-1877, for instance, city health officer J. L. Meares bragged that not only had he ordered every house in Chinatown thoroughly fumigated, "but the whole of the Chinese quarter was put in a sanitary condition that it had not enjoyed for ten years."[58] Similar comments were made at the time of the bubonic plague in 1900-1901 when nearly every house in the district was disinfected and fumigated.

In the nineteenth century medical care in Chinatown was largely provided by herbalists and pharmacies in the classic tradition of Chinese medicine. As late as 1900, no Chinese physicians appear to have been licensed to practice medicine in the state of California; in fact, not until 1908 was the Medical Department of the University of California in San Francisco to graduate a physician of Chinese origin.[59] Some Chinese of the merchant class did seek treatment from Caucasian physicians, usually for surgical care not available from Chinese practitioners.[60] In the I880's a few church missions in Chinatown also began offering the services of white female physicians for pediatric and obstetrical care. Throughout the nineteenth century, however, the vast majority of Chinese were unwilling to consult Caucasian doctors because, as one historian has noted, "the language barriers, the higher fees, and strange medications and methods were too much to assimilate."[61]

The reluctance on the part of the Chinese to seek medical attention outside of Chinatown accounted in part for their low admission rate to the San Francisco City and County Hospital and to the Almshouse during the last century. An examination of the statistics on admissions to the city and county hospital for the years 1870-1897 reveals that less than .1 percent of the hospital inpatients were of Chinese origin, whereas the Chinese population in the city varied from 5 to 11 percent of the total population. Statistics on admissions to the Almshouse disclose an even lower admission rate: of 14,402 admissions from 1871 to 1886, only 14 cases were of Chinese origin.

Obviously, the low admission rate of the Chinese to municipal facilities cannot be attributed entirely to reluctance to seek Western-style care. An 1881 article in the San Francisco Chronicle, headlined "No Room for Chinese: They are Denied Admission to the County Hospital," referred to a resolution of the Board of Health, adopted several years earlier, that had essentially closed City and County Hospital to Chinese patients.[62]

The article pointed out that in the fall of 1881 the Chinese consul had petitioned the Board of Health on behalf of an ailing Chinese immigrant who desired to gain admission to the city and county facility. Fearing an influx of Chinese patients with chronic diseases, the board passed a resolution that all Chinese patients who thereafter requested care were to be assigned to a separate building on the Twenty-Sixth Street hospital lot.[63] Apparently, this policy remained in effect throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century. A document dated 1899 noted that the City and County Hospital only opens its doors to a limited number of [Chinese] patients. The remainder of the patients are taken to the small, dismal Charnel-house established by the Chinese Companies, and known as the "Hall of Great Peace," or else to the Leper Asylum or Pest-House.[64]

Although the ban on Chinese patients at both the City and County Hospital and the Almshouse was common knowledge, city officials continued to claim that San Francisco opened its municipal facilities to the sick and poor of any nationality.[65]

Because of the difficulties inherent in obtaining care at municipal expense, the Chinese community sought from an early date to fund a well-equipped hospital within the Chinatown area. Dr. Stout, in his congressional testimony in 1877, mentioned that the Chinese desired very much to establish a general hospital and a smallpox hospital, similar to those built by the French and German communities. Reportedly, the Chinese were willing "to pay liberally and freely" to establish a hospital, with patient care to be provided by both white and Chinese physicians.[66] (In order to secure approval from the Board of Supervisors for the erection of such a hospital, the Chinese community recognized that their Physicians would have to work in conjunction with state-licensed Caucasian physicians.)

Nothing more is heard of any hospital plans until the early 1890's when land was purchased in the southern outskirts of San Francisco in the name of the Chinese consul general of San Francisco. Plans were drawn up for a hospital, and funds were collected both locally and from foreign sources. When construction of the hospital was about to begin, "city authorities forbade further proceedings on the ground that the promoters only intended to use objectionable Chinese systems of medical treatment."[67] It can be surmised that the real objections were to the proposed location of the hospital outside the perimeter of Chinatown.

In 1899, the community planned to rent a house in a "suitable locality" to be fitted up as a hospital and dispensary where only practitioners with American or European diplomas were to be allowed to visit the patients. The dispensary was to give free advice and medicine to indigent clinic patients; the hospital was to consist of twenty-five beds for use by both clinic and paying patients. The Chinese Hospital (Yan-Chai-i-yn) was incorporated under California law in March, 1899. At that time, twenty-one persons (including twelve Caucasians) pledged to become members of the hospital by payment of an annual subscription of $5. Except for the Chinese consul general, the officers of the hospital's first governing board were to be prominent members of the white community.[68] This project, too, must have been shelved because no further trace of this hospital can be found.

Dr. Trauner is a research specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, Medical Center in the History of Health Science Department.

Notes

55. U.S. Congress, Senate, Report of the Joint Special Committee to Investigate Chinese Immigration, 44 Cong., 2 Sess., 1877, p. 646.

56. "Mongolian Leprosy," 236.

57. Examination of the testimony of Arthur B. Stout, M.D., before Joint Special Committee to Investigate Chinese Immigration, Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration, 1885, p. 311.

58. Municipal Reports, 1877, p. 398.

59. Transactions, 1901, p. 386. See also "Medical School: Directory of Graduates, 1864-1921," University of California Bulletin, third series, 15:3.

60. Royal Commission, 1885, p. 224.

61. Chinn, A History of the Chinese in California, 78.

62. San Francisco Chronicle, November 20, 1881.

63. Ibid.

64. The Chinese Hospital of San Francisco (Oakland: Carruth & Carruth, 1899), p. 2.

65. "Mongolian Leprosy," 236.

66. Report of Joint Special Committee to Investigate Chinese Immigration, 1877, p. 647.

67. Chinese Hospital of San Francisco, 1899, p. 2.

68. Ibid., p. 6.