19th Century Medical Self-Help, Part II: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) (added abstract) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

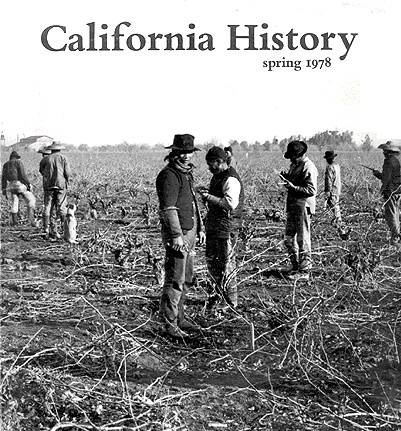

''by Dr. Joan B. Trauner, Excerpted from the version which appeared in ''California History'', Spring 1978, Vol. LVII, No. 1, courtesy of the California Historical Society'' | |||

[[Image:chinatwn$tung-wah-dispensary.jpg]] | [[Image:chinatwn$tung-wah-dispensary.jpg]] | ||

'''Tung Wah Dispensary, opened in 1900 by the Chinese Six Companies at 828 Sacramento St.''' | '''Tung Wah Dispensary, opened in 1900 by the Chinese Six Companies at 828 Sacramento St.''' | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''Outbreak of the bubonic plague in Chinatown in 1900 prompted residents to take both social and political action, forming their own health care system and taking legal action against anti-Chinese discrimination. The reluctance of Chinese and Chinese-American San Franciscans to receive health services outside of Chinatown well after the containment of the plague speaks to the lasting effects of medical discrimination and distrust in San Francisco.''' | |||

|} | |||

Shortly thereafter bubonic plague was discovered in Chinatown; public officials suddenly were faced with the fact that no health facilities existed in Chinatown for the care of plague victims. As early as May, 1900, the surgeon general of the Marine Hospital Service, Dr. Walter Wyman, suggested that one of the more "substantial" buildings in the area should be converted into a pest hospital.[69] The War Department, on the other hand, preferred to see the Chinese quarantined on Angel Island. Neither plan went into effect, and in April, 1901, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors appropriated funds for the erection of a hospital in Chinatown. The city auditor immediately declared that the appropriation was illegal, and accordingly, the hospital was never constructed.[70] | Shortly thereafter bubonic plague was discovered in Chinatown; public officials suddenly were faced with the fact that no health facilities existed in Chinatown for the care of plague victims. As early as May, 1900, the surgeon general of the Marine Hospital Service, Dr. Walter Wyman, suggested that one of the more "substantial" buildings in the area should be converted into a pest hospital.[69] The War Department, on the other hand, preferred to see the Chinese quarantined on Angel Island. Neither plan went into effect, and in April, 1901, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors appropriated funds for the erection of a hospital in Chinatown. The city auditor immediately declared that the appropriation was illegal, and accordingly, the hospital was never constructed.[70] | ||

| Line 19: | Line 27: | ||

Today, the outright discrimination against the Chinese has ceased. Nevertheless, a continuing phenomenon is the reluctance of many Chinese--particularly among the aged or non-English speaking immigrant groups--to seek health services outside of the Chinatown area. Thus, while members of the Chinese community routinely seek medical care in hospitals, offices, and clinics throughout San Francisco, Chinatown itself continues to present a unique situation for the organization of health services. In one sense, the Chinese ceased being medical scapegoats by 1905; after that date, advances in medical science made obsolete the nineteenth-century policy of condemning the Chinese as "carriers of alien disease." However, the failure of the City and County of San Francisco to provide health services within Chinatown was to have a more enduring effect. As late as 1967, the only outpatient facility furnishing acute medical services to the Chinese indigent in Health District IV (Chinatown-North Beach) was the Telegraph Hill Neighborhood Clinic, located in North Beach and funded in part by the United Crusade and by the San Francisco Department of Public Health.[82] The city facility--the Northeast Health Center--was housed during this period in the basement of the Ping Yuen Housing complex; a tuberculosis clinic, a well-baby clinic, dental services, an immunization center, and a public health nursing service were all provided in 1200 square feet of converted laundry space.[83] In other words, a paucity of medical services existed in Chinatown as late as the 1960's; not until the 1970's was the situation finally remedied. | Today, the outright discrimination against the Chinese has ceased. Nevertheless, a continuing phenomenon is the reluctance of many Chinese--particularly among the aged or non-English speaking immigrant groups--to seek health services outside of the Chinatown area. Thus, while members of the Chinese community routinely seek medical care in hospitals, offices, and clinics throughout San Francisco, Chinatown itself continues to present a unique situation for the organization of health services. In one sense, the Chinese ceased being medical scapegoats by 1905; after that date, advances in medical science made obsolete the nineteenth-century policy of condemning the Chinese as "carriers of alien disease." However, the failure of the City and County of San Francisco to provide health services within Chinatown was to have a more enduring effect. As late as 1967, the only outpatient facility furnishing acute medical services to the Chinese indigent in Health District IV (Chinatown-North Beach) was the Telegraph Hill Neighborhood Clinic, located in North Beach and funded in part by the United Crusade and by the San Francisco Department of Public Health.[82] The city facility--the Northeast Health Center--was housed during this period in the basement of the Ping Yuen Housing complex; a tuberculosis clinic, a well-baby clinic, dental services, an immunization center, and a public health nursing service were all provided in 1200 square feet of converted laundry space.[83] In other words, a paucity of medical services existed in Chinatown as late as the 1960's; not until the 1970's was the situation finally remedied. | ||

'' | ''Dr. Trauner is a research specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, Medical Center in the History of Health Science Department.'' | ||

[[19th Century Medical Self-Help | Return to Part 1]] | |||

[[ | [[Image:Chinatwn%24exclusion-act%24chs_itm%24ch-cover.jpg]] | ||

'''Footnotes''' | '''Footnotes''' | ||

Latest revision as of 16:44, 7 July 2024

Historical Essay

by Dr. Joan B. Trauner, Excerpted from the version which appeared in California History, Spring 1978, Vol. LVII, No. 1, courtesy of the California Historical Society

Tung Wah Dispensary, opened in 1900 by the Chinese Six Companies at 828 Sacramento St.

| Outbreak of the bubonic plague in Chinatown in 1900 prompted residents to take both social and political action, forming their own health care system and taking legal action against anti-Chinese discrimination. The reluctance of Chinese and Chinese-American San Franciscans to receive health services outside of Chinatown well after the containment of the plague speaks to the lasting effects of medical discrimination and distrust in San Francisco. |

Shortly thereafter bubonic plague was discovered in Chinatown; public officials suddenly were faced with the fact that no health facilities existed in Chinatown for the care of plague victims. As early as May, 1900, the surgeon general of the Marine Hospital Service, Dr. Walter Wyman, suggested that one of the more "substantial" buildings in the area should be converted into a pest hospital.[69] The War Department, on the other hand, preferred to see the Chinese quarantined on Angel Island. Neither plan went into effect, and in April, 1901, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors appropriated funds for the erection of a hospital in Chinatown. The city auditor immediately declared that the appropriation was illegal, and accordingly, the hospital was never constructed.[70]

About the time that plague was discovered in Chinatown, the Chinese Six Companies realized that it was imperative for the Chinese community to organize its own health care system. The result was the Tung Wah Dispensary which opened in 1900 at 828 Sacramento Street. The dispensary, which employed both Western trained physicians and Chinese herbalists, was funded entirely by the Chinese Six Companies, and this dispensary was to be the forerunner of the present-day Chinese Hospital which opened its doors in April, 1925.[71]

In 1900, in addition to financing the dispensary, the Chinese Six Companies instituted legal action to prevent local, state, and national officials from enforcing discriminatory measures aimed at the Chinese. In court, their attorneys won the right for non-licensed Chinese physicians to attend autopsies conducted under the jurisdiction of the San Francisco Board of Health. Similarly, their lawyers forced the courts to end the quarantine of Chinatown as ordered by the Board of Health. In May, 1900, when the U.S. Marine Hospital Service imposed a ban on interstate travel by Asiatics, the secretary of the Chinese Six Companies obtained a restraining order from the U.S. circuit court, arguing that such a ban was unfair class legislation.[72]

Public health officials were infuriated by the legal tactics of the Chinese Six Companies. Dr. J. J. Kinyoun, federal quarantine officer for San Francisco, expressed his indignation in the following statement:

The various injunctions which have been entertained by both state and federal courts ... have all conspired to convince the Chinese Six Companies that they in nowise consider the Chinamen amenable to observe or comply with the health laws of the city, state, or United States. The attitude assumed by this powerful corporation forms a good excuse for the individual Chinaman to follow suit and set at naught and defiance any or all rules and regulations which are considered necessary for the sanitary protection of the citizens of this state and country.[73]

Although the Chinese were extremely hostile to the official anti-plague measures, this lack of cooperation stemmed in part from their unfamiliarity with public health procedures. When quarantine of Chinatown was first instituted, the Chinese attempted to prevent door-to-door inspection by locking up their homes and shops.[74] When health officials attempted to vaccinate the Chinese with Haffkine prophylactic serum, riots broke out in Chinatown.[75] Finally, when health officials came into the area to search for victims of the plague, the sick were reportedly hidden in the cellars and "subterranean passages" of Chinatown.[76] Health officials despaired, neither understanding nor sympathizing with the motives of the Chinese. In the words of J. J. Kinyoun: "We never can expect to accomplish in our dealings with this race what we intend to do."[77] Accordingly, in 1905 after the first episode of the plague had ended, public health officials retreated from Chinatown, unofficially delegating the Chinese Six Companies with the responsibility of caring for the health needs of the Chinese community.

In the years to come, the overcrowded living conditions in Chinatown were to result in a high incidence of tuberculosis. For instance, the average yearly death rate from tuberculosis for the years 1912-1914 was 622 deaths per 100,000 as compared to a citywide average of 174.[78] In 1929, after the introduction of tuberculin testing of cattle and pasteurization of milk, the Chinese mortality rate was 276 deaths per 100,000 as compared to a citywide average of 8 3.[79] Yet, until 1933 no public health facilities existed within Chinatown for the diagnosis or treatment of tuberculosis. One 1915 health report noted the absence of clinics in the Chinatown area and stated as follows: "The Six Companies is probably in a better position than any other group to cooperate with the Board of Health in instituting curative and preventative measures among their own people."[80] In other words, the city had adopted a "hands off" policy with regards to health care among the Chinese. Not until March 1933, when the Chinese Health Center was established in the nurses' room at the Commodore Stockton School, would the city attempt to cope even half-heartedly with the tuberculosis problem in Chinatown.[81]

Today, the outright discrimination against the Chinese has ceased. Nevertheless, a continuing phenomenon is the reluctance of many Chinese--particularly among the aged or non-English speaking immigrant groups--to seek health services outside of the Chinatown area. Thus, while members of the Chinese community routinely seek medical care in hospitals, offices, and clinics throughout San Francisco, Chinatown itself continues to present a unique situation for the organization of health services. In one sense, the Chinese ceased being medical scapegoats by 1905; after that date, advances in medical science made obsolete the nineteenth-century policy of condemning the Chinese as "carriers of alien disease." However, the failure of the City and County of San Francisco to provide health services within Chinatown was to have a more enduring effect. As late as 1967, the only outpatient facility furnishing acute medical services to the Chinese indigent in Health District IV (Chinatown-North Beach) was the Telegraph Hill Neighborhood Clinic, located in North Beach and funded in part by the United Crusade and by the San Francisco Department of Public Health.[82] The city facility--the Northeast Health Center--was housed during this period in the basement of the Ping Yuen Housing complex; a tuberculosis clinic, a well-baby clinic, dental services, an immunization center, and a public health nursing service were all provided in 1200 square feet of converted laundry space.[83] In other words, a paucity of medical services existed in Chinatown as late as the 1960's; not until the 1970's was the situation finally remedied.

Dr. Trauner is a research specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, Medical Center in the History of Health Science Department.

Footnotes

69. Public Health Reports, XV (May 15, 1900): 1255.

70. Link, A History of Plague, 4.

71. T. J. Gintjee and Howard Johnson, M.D., "San Francisco's First Chinese Hospital," Modern Hospital, XXV (Oct., I925), p. 283. See also Chinese Hospital, 40th Anniversary: Chinese Hospital (Hong Kong: Wing On Shing, [1964]), p. 1.

72. Link, A History of Plague, 4-5.

73. Kinyoun, quoted in Kellogg, Transactions, (1901, 1) 85.

74. Link, A History of Plague, 4.

75. Society Proceedings of the California Academy of Medicine, Occidental Medical Times, XIV (July, 1900): 226.

76. "Plague on the Pacific Coast," Journal of the American Medical Association, XLIX (Dec. 14, 1907): 2000. See also Amold Genthe and Will Irwin, Old Chinatown (New York: Mitchell Kennerly, 1919), p. 154.

77. Kinyoun, quoted in Kellogg, Transactions, 1901, p. 89.

78. San Francisco Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, A Report of the Tuberculosis Situation in San Francisco Submitted to the Department of Public Health of the City and County of San Francisco (San Francisco: San Francisco Association for the Study and Prevention of Tuberculosis, 1915), p. 20.

79. J. C. Geiger, M.D., Emmet E. Sappington, M.D., Roslyn C. Miller, and Hilda F. Welke, The Health of the Chinese in An American City: San Francisco (San Francisco: San Francisco Department of Public Health, 1939), p. 24.

80. A Report of the Tuberculosis Situation in San Francisco, 1915, p. 20.

81.J. C. Geiger, M.D., Emmet E. Sappington, M.D., Roslyn C. Miller, and Hilda F. Welke, The Health of the Chinese in An American City: San Francisco (San Francisco: San Francisco Department of Public Health, 1939), p. 5.

82. San Francisco Chinese Community Citizens' Survey and Fact Finding Committee, Abridged Report, August 15, 1969 (San Francisco, 1969), p. 96.

83. Ibid., 99.