Emergence of Environmental Justice in Richmond: Difference between revisions

(need photo credits...) |

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) (added abstract) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

''by Jacob Soiffer, 2015'' | ''by Jacob Soiffer, 2015'' | ||

[[Image: | [[Image:File--CF-627-Wartime-Richmond-Shipyard.jpg]] | ||

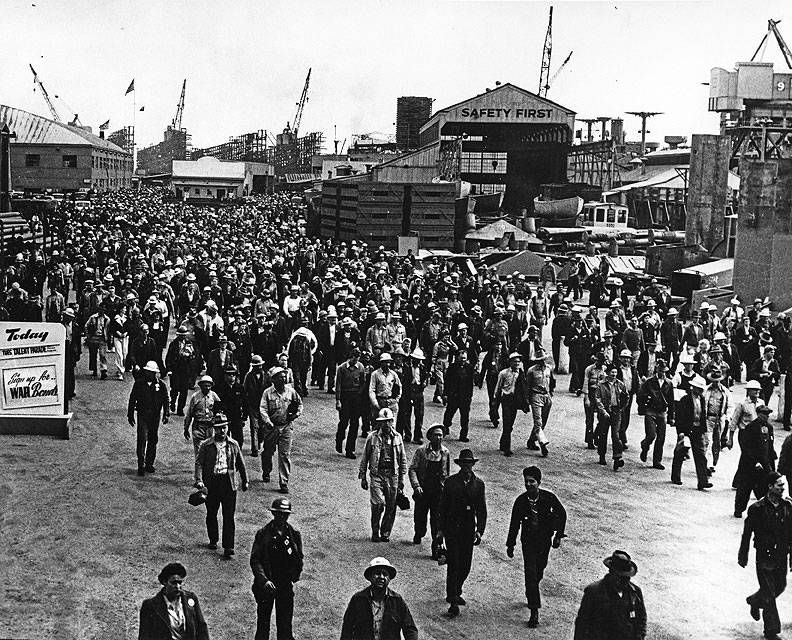

''' | '''Wartime employees shift change, Kaiser Richmond shipyard #1, circa 1943. ''' | ||

''Image courtesy Kaiser Permanente Heritage Resources.'' | |||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''Richmond’s distinct history in relation to industry has provided the grounds for its significant participation in the environmental justice movement, as its proximity to oil refineries has brought toxins to the air and water. Political contestation over the relationship between race and space has also played an important role in Richmond’s environmental activism over time as the city’s demographics have shifted.''' | |||

|} | |||

[[Image:Addressing-injustice.png|left]] | [[Image:Addressing-injustice.png|left]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:08, 7 July 2024

Historical Essay

by Jacob Soiffer, 2015

Wartime employees shift change, Kaiser Richmond shipyard #1, circa 1943.

Image courtesy Kaiser Permanente Heritage Resources.

| Richmond’s distinct history in relation to industry has provided the grounds for its significant participation in the environmental justice movement, as its proximity to oil refineries has brought toxins to the air and water. Political contestation over the relationship between race and space has also played an important role in Richmond’s environmental activism over time as the city’s demographics have shifted. |

In the past few decades the city of Richmond has come to be known both in the East Bay and nationally as a powerful center for the environmental justice movement and for intersectional, grassroots community organizing—a key “battlefield in this global struggle.”(1) In 2014, Richmond took the national stage when left-leaning candidates with the Richmond Progressive Alliance soundly defeated the candidates backed by local political broker Chevron, despite the oil giant outspending the other candidates by a 20-to-1 margin.(2) This followed high-profile successes of the past eight years, in which Richmond elected and re-elected Gayle McLaughlin, the first Green Party mayor in an American city of its size. These recent victories have their roots in decades of struggle, in which numerous organizations have approached issues of race, space, equity, and health from a number of angles.

The terrain in which environmental justice organizations and existing coalitions emerged was engendered by Richmond’s unique history: its demographic changes, its evolving relationship with local industry, and the tactical choices made by organizers on the ground. The example of Richmond’s political landscape can serve as a microcosm for the broader challenges and promises facing the environmental justice movement, and the lessons it brings to the environmental movement and movements for justice more broadly.

Richmond: (Post)-Industrial Heartland

Richmond, a city of roughly one hundred thousand residents just north of Berkeley in the East Bay, has a long history of sharing space with heavy industry. The Standard Oil plant, which later became Chevron, opened in 1902 — three years before the city was incorporated — and by 1904 was the world’s second largest oil refinery.(3) Other industry soon followed, including the California Wine Association in 1906, Pullman Railroad Company in 1909,(4) and the Ford Motor Company in the early 1930s.(5) These industries shaped Richmond’s economic, political, and social landscape. In particular, for much of the 20th century, Standard Oil/Chevron has had a powerful hold on city politics, being the city’s biggest tax-payer and at one point employing half of its residents. One Standard Oil employee, W. W. Scott, was elected Mayor of Richmond four times, and employees and business-friendly politicians were frequently able to gain positions of power because of the support they received from the industry. (6)

The rapid growth of wartime industry in the Richmond shipyards during World War II caused a shift in Richmond’s sociopolitical makeup through a massive migration of workers into the city. The wartime industry grew partly because Richmond’s real estate boosters advertised it as a city where corporate power could go unchecked. According to them, the Richmond harbor was not “dictated by petty politicians” because it was “in private ownership,” and the city a “bulwark of Conservativism...with resultant low taxation” where “strikes were unknown.”(7) The new residents were on the whole much younger and much less white than the city had been in the past. While the labor force multipled by sixteen, Richmond’s Black population was fifty times larger by the end of the war.(8) The number of women working also increased—Richmond was one of the origins of the famous “Rosie the Riveter” image.(9) Richmond’s Black population boomed. Like the new white emigrants, many of them were poor workers from the South and Plains states, and strong racial and ethnic hierarchies emerged and racial tensions increased. From the start, “native” (native-born) Americans with money were at the top of the pyramid, with the working-class whites and white immigrants below them, and the poor Black and Hispanic immigrants below them.(10) On the docks where Black and white workers often shared space (though Blacks were excluded from or marginalized within the local unions), slurs were common, and when race riots erupted in Vallejo during the War it set the city of Richmond on edge.

Richmond’s social ills were formed at the nexus of race and space. As they entered the city in the 1940s, Blacks were commonly denied entrance or services at many establishments, and received unequal pay for their work. A “black crescent”(11) of lower-quality housing (much of it temporary wartime housing built by the government) formed “in the vicinity of existing industrial operations because the land was cheap and the people were poor.”(12) As late as 1950, the vast majority of Blacks lived in badly maintained temporary war housing, with the rest living largely in North Richmond, which the Chamber of Commerce repeatedly pushed to be rezoned for industrial, not residential, use.(13) As wartime industry left, the city government repeatedly tried to evict residents from wartime housing without providing alternative housing and were confronted by a series of powerful resident “no-rent strikes.”(14)

It was around these issues of race and space that Richmond’s “first major political contestations”(15) emerged, and similar issues—corporate control of city government, tensions between the community and police, high crime, and the segregation of low-income people of color into housing and schools dangerously close to heavy industry—have persisted into the 21st century. Resistance to toxicity and environmental injustice in Richmond emerged from this political culture concerned less with an abstract notion of “the environment” than with the real political contestations over space and power and the real implications of environmental racism.

Toxicity and the West County Toxics Coalition

An explosion at the Chevron refinery in Richmond, 2012.

By the 1980s, underregulated industry had for years been operating in Richmond without any heed to the public health effects of toxicity in the city’s air and water. Almost one-fifth of California’s Superfund sites—locations which the EPA has declared contaminated with hazardous materials—are in Richmond.(16) The Chevron plant, in particular, has been a frequent source of toxicity and danger to local residents: it had 304 industrial accidents between 1989 and 1995 alone.(17) According to Henry Clark from the West County Toxics Coalition, North Richmond—the area nearest to the refinery—was “on the frontline of the chemical assault” when he was growing up there. He remembers, like others in the area, “finding the leaves on the tree burnt crisp overnight from chemical exposure, or going outside and the air would be so foul that you would literally have to grab your nose and try to not breathe the air and go back in the house and wait until it was cleared up.”(18) Children in the local elementary school had grown used to toxic disaster evacuation drills.(19) Although earlier on in Richmond’s history Standard Oil had been a major employer of Richmond residents, these days “very few people from the surrounding community that live around the refinery...are actually employed there,” souring the refinery’s basis for its relationship with the community.(20)

Industry grew near low-income neighborhoods where it was less likely to face political resistance and regulation, and low-income people of color were then pushed closer and closer to the toxic sites as rents rose elsewhere and the land became less desirable. Unsurprisingly, 79% of those living near the Chevron plant were low-income people of color.(21)

Founded in 1987, the West County Toxics Coalition has for almost thirty years been a one of Richmond’s strongest environmental and social justice organizations.(22) It emerged with local roots, building off of community connections and focusing on the environmental justice issues particular to Richmond, but also from interaction with national movements against toxicity and for social and racial justice. Ahmadia Thomas, one of WCTC’s early members, remembers how many of the organizers that ended up together in the organization began organizing on different issues, including housing issues, tenants’ rights, and redlining—coming from a background of social and racial justice, not traditional environmentalism. The coalition was created by a group called Citizens’ Action, a “spin-off” of the Oakland ACORN branch. In Thomas’s eyes, few folks in the community thought about toxicity or pollution in any political sense before WCTC came along: “they smelled something, and that was it.” For the most part, their backgrounds were not in environmental work or traditional environmental politics.(23)

Although the organization had roots in the local community, it was also formed out of interaction with a growing national anti-toxics and environmental justice movement. According to Clark, its long-time Executive Director, the organization was actually founded as an extension of the National Toxics Campaign—Craig Williams, WCTC’s founder, was sent from Boston to “build an organization” in Richmond and “train some native leadership.”(24) It also grew stronger thanks to the strong presence of the environmental movement in the Bay: the Sierra Club, headquartered in the Bay, was “involved” in its early stages, and Communities for a Better Environment, headquartered in San Francisco, “furnished the group with technical assistance and documentation” and has continued to play an active role in the community since.(25)

Over the years WCTC has launched a number of campaigns to protect the community from toxicity, with some powerful successes. Its first campaign succeeded in pressuring city agencies to abandon a plan to build a waste-to-energy incinerator near North Richmond’s Verde Elementary School.(26) In the early- to mid-90s, WCTC worked to bring class-action lawsuits against Safeway for a fire that endangered residents and ran a related public health forum.(27) When part of the port area where United Heckathorn and other chemical companies had caused dangerous contamination was labelled a superfund site, WCTC helped organize community participation in the removal process, and when it was announced that the waste was going to be shipped to another unsafe location near a low-income community of color in Mobile, Arizona, Richmond residents and WCTC agitated in solidarity with the people of Mobile, successfully forcing the waste to be moved to an area in Utah where the community didn’t have problems with the waste being there because it was farther from residential areas.(28) As Clark puts it: “To say ‘Not in my backyard, but in someone else’s backyard, that’s OK...'that ain’t really environmental justice.”(29)

Although WCTC doesn’t have any attorneys on staff, filing class-action lawsuits for affected community members have consistently been a power tool in its arsenal. After a General Chemical Company explosion in 1993 sent 20,000 people to the hospital, a class-action lawsuit WCTC worked on won around $180 million in reparations, including money for a new community health center and, crucially, sirens for the city’s emergency warning system.(30)

Apart from the superfund sites, many of the most influential environmental justice struggles in Richmond have dealt with the Chevron refinery and associated infrastructure. One of their first early aims was to win “the right to negotiate” with Chevron, to bring Chevron to the bargaining table—which they were able to do after a visit by Reverend Jesse Jackson and some connections they had through CBE attracted Chevron’s interest.(31) However, their first major victory in terms of actually curtailing the pollution related to the Chevron refinery came when Chevron attempted to acquire a permit to expand its Ortho incinerator, which WCTC had been opposed to for years. In 1997, after two years of door-knocking, organizing community leaders, and “public education,” WCTC and allied organizations succeeded in pushing Chevron to withdraw its request for a permit and they shut down the incinerator entirely.

Their relationships with other organizations have been a complicated bag: Clark in particular has taken aim at “big ten” environmental organizations like the Sierra Club and Greenpeace for not addressing “issues that impacted communities of color” because they didn’t consider themselves “rock-the-boat type of organizations” or were concerned about their funding, which in some cases came from large corporations.(32) Even when told by the growing national environmental justice movement that they weren’t “inclusive” or “had been working in opposition to environmental justice,” these environmental groups often only responded by “hiring some person of color on their staff or something,” without any fundamental change in their politics or strategies.(33) Similarly, Clark has also felt some frustration with many of the local agencies, nonprofits, and social service groups in Richmond, which he and others at WCTC have felt don’t do enough to challenge Chevron’s power in the community because they are funded by Chevron or have pro-Chevron boards.(34)

WCTC has had good relationships with the Asian-Pacific Environmental Network (APEN) and Communities for a Better Environment (CBE) in Richmond, other groups committed to community organizing, challenging corporate power, and a progressive vision. It is from this nexus of interests and groups that Richmond’s environmental justice movement has emerged over the past few decades, and began to fundamentally shift power away from Chevron and Richmond’s other corporate polluters.

APEN & Richmond’s Shifting Demographics

Henry Clark, right, and others protest against Chevron.

Photo: Richmond Confidential

Much of the shift towards a uniquely intersectional environmental justice politics in Richmond may have been enabled by the demographic transformations in Richmond in the last thirty years. The large spike in Richmond’s Latin@ and Asian-Pacific Islander populations has been the dominant trend in Richmond’s demographics since 1980,(35) with Latin@s now comprising a plurality of the population and Laotian and Hmong immigrants an important, and economically marginalized, subset.(36) Although the city has seen a resulting uptick in interracial violence,(37) new possibilities have also opened up for multiracial organizing, with alliances forged between progressive leaders in the Laotian, Latin@, and African-American communities. Arguably, this has empowered progressive voices across the board, while opening up a “deeper fissure between black progressives and the entrenched pro-business black leadership.”(38) In a city with frequent African-American leadership over the last half-century, during McLaughlin’s two terms as mayor, African-American representation on the city council dropped to its lowest point in fifty years.(39) It remains to be seen whether this trend will continue, or how Richmond’s continuously changing demographics will shape its political landscape moving forward.

APEN has done powerful work in Richmond organizing the local Laotian community for

environmental justice, via the Laotian Organizing Project, and it has played an important role in the emergence of Richmond’s environmental justice movement. Much of the work that organizers with APEN have done has been in tandem with WCTC and other organizations in the area. For example, while WCTC and others lobbied to get the first emergency warning sirens installed, it was APEN who made sure the warning calls were timely and in residents’ native languages, after calls came late or only in English following a 1999 explosion at the Chevron plant.(40) Over the years, APEN has brought a uniquely intersectional analysis to the work, focusing not just on racial inequity but also on the “social and political rights” of “new immigrants and their children”(41) and on gender justice, especially regarding reproductive health issues and the empowerment of women within the communities they work with.(42) As conservatives in California led a backlash against immigrants and people of color in the 1990s and 2000s via Propositions 187, 209, and 227, and Clinton-era changes in welfare tied welfare to citizenship, cutting off many immigrant families, racial and immigrant justice groups like APEN fought hard to defend their communities, and a political analysis that uplifted immigrants and people of color became more heavily incorporated into the environmental justice movement.(43)

Richmond’s Progressive Coalition & the National Movement

One of the broadest shifts environmental politics nationally over the last couple of decades has been the rise of the environmental justice movement, and Richmond has played a key role in its formation. Community organizers from Richmond served as representatives at the first People of Color Environmental Justice Summit in 1991, which Clark cites as “the official formation of the environmental justice movement.”(44)

Recently, Richmond has played a key role in the growing national Climate Justice Alliance and has served as a powerful example to other communities fighting for a transition towards equity and sustainable and just energy production. The successes of the Richmond Progressive Alliance and others in breaking Chevron’s hold on the city’s politics have gained national media attention, and the Richmond General Plan 2030, the city’s progressive 2012 plan for land-use, housing, conservation, and other aspects of development, offers a glimpse of how the city can develop moving forwards in a way that prioritizes justice and a healthy relationship with the environment.(45)

Notes

1. Ellen Choy and Ana Orozco, “Chevron in Richmond: Community-Based Strategies for Climate Justice.” Race, Poverty &

the Environment, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Fall 2009), 43.

2. Carolyn Jones, “Chevron’s $3 million backfires in Richmond election.” SFGate, November 5, 2014.

3. Robert Wenkert, A historical digest of Negro-White relations in Richmond, California (Berkeley: Survey Research Center, University of California, 1967), 2.

4. Wenkert, A historical digest, 3.

5. Wenkert, A historical digest, 6.

6. Wenkert, A historical digest, 9.

7. Wenkert, A historical digest, 10.

8. Bindi V. Shah, Laotian Daughters: Working toward Community, Belonging, and Environmental Justice (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2011), 28.

9. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 28.

10. Wenkert, A historical digest, 14.

11. Manuel Pastor, “Black, brown, white, and green: race, land use, and environmental politics in a changing Richmond.” Social justice in diverse suburbs : history, politics, and prospects. Edited by Christopher Niedt. (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2013), 159.

12. Regina Austin and Michael Schill, “Black, Brown, Poor & (and) Poisoned: Minority Grassroots Environmentalism and the Quest for Eco-Justice.” Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy, Vol. 69 (1991), 70.

13. Wenkert, A historical digest, 36.

14. Wenkert, A historical digest, 39.

15. Pastor, “Black, brown, white, and green,” 159.

16. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 28.

17. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 29.br>

18. Henry Clark, interviewed by Carl Wilmsen, "Fighting toxic emissions in Richmond, California, 1984-2000", Regional Oral History Office, the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, December 6, 1999.

19. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 21.

20. Clark, interview, 1999.

21. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 32.

22. Livingston, Handbook of Black American Health: The Mosaic of Conditions, Issues, Policies, and Prospects (Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994), 325.

23. Ahmadia Thomas, interviewed by Carl Wilmsen, "Fighting toxic emissions in Richmond, California, 1984-2000," Regional Oral History Office, the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, February 22, 2000.

24. Clark, interview, 1999.

25. Robert Doyle Bullard, Confronting Environmental Racism: Voices from the Grassroots, (South End Press, 1993), 33.

26. Clark, interview, 1999.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

29. Sarah Bernard, “Henry Clark and three decades of environmental justice.” Richmond Confidential, December 6, 2012.

30. Clark, interview, 1999.

31. Ibid.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid.

35. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 31.

36. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 28.

37. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 31.

38. Pastor, “Black, brown, white, and green,” 156.

39. Pastor, “Black, brown, white, and green,” 155.

40. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 58.

41. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 50.

42. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 120.

43. Shah, Laotian Daughters, 33.

44. Clark, interview, 1999.

45. “Richmond General Plan 2030.” City of Richmond, CA Official Website. Web. 2012.