Work Boots Step Out of the Closet: Difference between revisions

(added link to related profile entries) |

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) (added abstract for series) |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

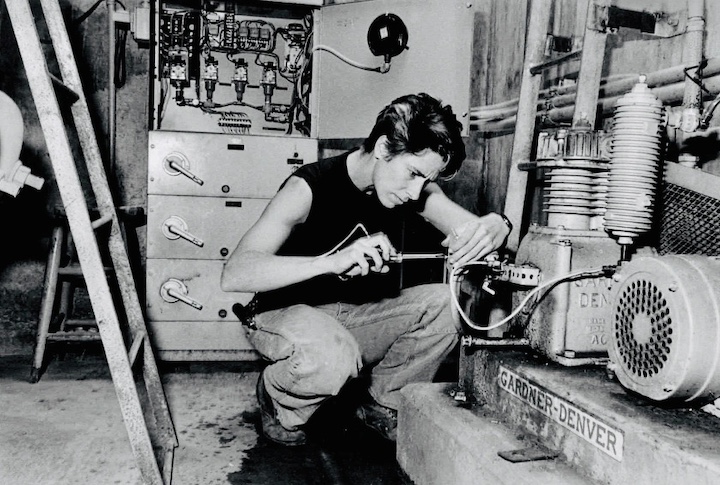

'''Working at a Water Department pump station. My shirt reads WOMEN WORKING.''' | '''Working at a Water Department pump station. My shirt reads WOMEN WORKING.''' | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" | '''After arriving in San Francisco in the 1970s, Molly Martin worked as an electrician and became highly active in advocating for women in the trades. This article is the third of a series of three pieces in which she documents the experience of doing this work: how she navigated stereotyping from men at blue collar work sites; union activity; and homophobia.''' | |||

|} | |||

“Come on you can tell me,” says Bobby. “Are you gay?” | “Come on you can tell me,” says Bobby. “Are you gay?” | ||

| Line 100: | Line 104: | ||

'''Read more about the Tradeswoman experience in San Francisco:''' | '''Read more about the Tradeswoman experience in San Francisco:''' | ||

[[What I Know About Stereotypes]] | |||

[[My First Day Local 6 | My First Day Local 6]] | [[My First Day Local 6 | My First Day Local 6]] | ||

[[category:1980s]] [[category:Potrero Hill]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:Civic Center]] [[category:Women]] [[category:Labor]] [[category:LGBTQI]] | [[category:1980s]] [[category:Potrero Hill]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:Civic Center]] [[category:Women]] [[category:Labor]] [[category:LGBTQI]] | ||

Revision as of 09:54, 23 July 2024

"I was there..."

by Molly Martin, 2020, originally published on tradeswomn blog

Working at a Water Department pump station. My shirt reads WOMEN WORKING.

| After arriving in San Francisco in the 1970s, Molly Martin worked as an electrician and became highly active in advocating for women in the trades. This article is the third of a series of three pieces in which she documents the experience of doing this work: how she navigated stereotyping from men at blue collar work sites; union activity; and homophobia. |

“Come on you can tell me,” says Bobby. “Are you gay?”

Bobby is a machinist who usually works in the machine shop but today he is helping me change fixtures in the warehouse at the corporation yard. I’m the only electrician and sometimes I need a helper. There was no laborer available and I am up on a 16-foot ladder.

The song by the Police, Every Breath You Take, is playing on the boom box he carries around with him.

“This sounds like a song about stalking,” I say. “It’s a threat.”

“Hmm, I never thought about it that way,” he says, “but I guess you’re right.”

I’ve been at the San Francisco Water Department for a few months and I’m getting along alright. Especially considering I’m the only tradeswoman there except for Amy, the only female plumber. Amy is out digging up the streets every day and so I rarely see her. Sometimes we convene a two-woman support group in the women’s restroom and it’s good to know she’s there.

I think about how to answer Bobby. It kind of annoys me that he would just ask me like that. But on the other hand I appreciate his directness. I like Bobby and he’s as close to a friend as I have among the men, but I know if I give him any information about my private life it will be all over the yard within 24 hours. Do I want all the guys in all the shops to know?

“That’s none of your business,” I reply.

Yeah, I’m a lesbian and my lover is Del, who works at Park and Rec. We were both female firsts—she the first carpenter and I the first electrician to work for the city of San Francisco. Being the first is always a burden. You are aware that you set the stereotype for all the women who come after you. You feel the whole of womankind rests on your shoulders. You know you can’t make mistakes but of course you do, and then you imagine all of womankind suffers.

Del is five foot two and slender but you don’t see her as small. Her wiry gray hair gives her a couple more inches of height. She’s got broad shoulders and large hands. And she gets power from her low voice; she sings tenor with a gay chorus, the Vocal Minority.

Del and I don’t live together but I spend a lot of time at her apartment on Potrero Hill with its sweeping view of the bay and downtown. At my place on Bernal Hill I have a roommate, Sandy, another electrician. She’s messy and has a lot of stuff and a coke head girlfriend I don’t like. So I often stay with Del. Truth is I can’t stay away. I’m mad for her.

Since I got in to the trades, my lovers have been tradeswomen. I can’t resist a woman with a toolbelt. The first woman I fell in love with was a carpenter. They say you either fall in love with her or you want to be her. For me it was both.

I watch my lover Nancy build a house. She wears dirty blue jeans and scuffed work boots. Sweat stains mushroom on her T-shirt, which reads Sisterhood is Powerful, under a women’s symbol with a fist in its center. Sweat drips from her nose and rolls down the side of her face. Her sun-bleached curly hair sticks out from under her hardhat.

Around her hips hangs the heavy leather carpenter’s belt. It has a metal ring for the hammer and slots for the tape measure and various other tools, and pouches for the nails of different sizes. A two-inch wide leather belt holds it around her ample hips. It’s helped by wide suspenders. She grabs a handful of nails and holds them with all the heads lined up in one direction, flips them down and pounds them in to the wood with great efficiency. Tanned arms bulge as she sinks nail after nail into the sill plate. She is focused and fast, the epitome of strength and ease. When she takes a break, she rolls a cigaret and lights it with a match put to her boot. She sucks in the smoke with obvious pleasure and even though I’m super allergic to smoke and it will set me off coughing, that is the sexiest thing I’ve ever seen. How could a gal not fall in love with this image of power, strength, purpose.

I was smitten and I’ve been smitten by tradeswomen ever since. And they are the only ones who really understand what I go through at work. A person’s got to have a partner she can whine to when she gets home.

Lately it’s Del who’s been having trouble at work. Dick, her foreman at the carpentry shop, doesn’t like women or queers. He does everything he can to make her work life difficult. If it weren’t for Dick, Del would get along just fine. She loves the work, not the harassment. She once overheard him call her a dyke. That’s a word we lesbians have reclaimed and embraced but he meant it in the old-fashioned derogatory way.

Negotiating homophobia and sexism at work is a balancing act for us. You just know that the foreman will use any excuse to lay you off. Del knows this too, that we women must always keep our cool in these situations, but sometimes she can’t help herself. She just loses her temper and then even she doesn’t know what she might do.

One time she held off an attacker with a hand saw. If you swing it at waist level, they can’t reach you. She swung the saw in a fit of rage, acting without thinking. In that case rage saved her ass, but mostly when this happens she leaves the confrontation feeling embarrassed that she could not control her emotions. She tells me I’m much better at not losing my cool and she ascribes her rage to her hot Italian blood.

I first met Del at a tradeswomen confab when I was working with the Wonder Woman Electric collective in 1978, but we didn’t get together as lovers until 1982 while we were organizing the first national tradeswomen conference that took place in Oakland the next year. We had both been working construction downtown before starting to work for the city of San Francisco.

“I lost my temper today and now I might lose my job,” Del told me one evening when I got over to her place after work.

By that time she was remorseful. “Why do I always lose my temper? How do you manage to stay so cool?”

I think the answer lays in the ways we learned to respond to stress and abuse when we were growing up. She was a caretaker type and I was oblivious. Del says she always felt like she had antennae, that she was super aware of her surroundings. I, on the other hand, would put on virtual blinders and just continue pretending nothing was going on. This method of avoiding conflict has served me well in the trades. I pretend not to see and often I really don’t.

Soon after we got together I accompanied her to visit her family in Chicago. Right away I felt at home. They are huggers, and loud talkers, people who like to cook and eat big family meals and who live in their basements, never using the living room upstairs where couches are covered with plastic. Her mother is part of a big Italian clan—all sisters except for one brother who is treated like a king but drowned out by loud women.

“Here’s what happened,” she said. “I wanted to get my paycheck earlier in the day than Dick wanted to give it out. I had an appointment and was leaving at noon. He was being totally obnoxious about it and I got really mad at him. I said “fuck it” and walked out without the paycheck. Now he’s trying to fire me for swearing at him. I wasn’t swearing at him, it was a general fuck-it. Anyway, just an excuse to fire me.”

“I’m scared,” she admitted.

“What are you gonna do now?” I asked, concerned.

“I don’t have a plan except to wait to see what he does next. Maybe it won’t go anywhere.”

A few days later Dick upped the ante. He set up a kangaroo court with his supervisors and friends in the yard who sat Del down and questioned her. She had no representation or support. It was just a set up.

That’s when Del went above the foreman’s head. We knew that the director of Park and Rec was an out gay man. Tom had gained a reputation as a respected department head who gave a shit about workers. He was also a player in the gay South of Market scene who (we heard) had tattoos all over his body. He always wore long sleeved shirts at work.

“Tom was absolutely great when I told him the story and showed him the daily journal I’d kept about the harassment,” she said to me. Soon after that Dick was fired.

Our gay ally had saved Del’s job, but what would have happened had he not been there?

“Are you out on the job,” she asked me later.

“Well, no. It’s none of their business.”

Del is a proponent of coming out at work. She says it’s better to give the guys the information so they will just stop gossiping about you. For women it might actually be a plus to be out. It’s a signal that you’re not interested in them romantically and you never will be, a good way to stop come-ons. Telling them you’re married with five kids works too.

At the tradeswomen conference she gave a workshop to help gay women come out.

“If we all come out we won’t be alone,” she says. “We’ll be supporting our lesbian sisters.”

She quoted Harvey Milk: “Every gay person must come out. As difficult as it is, you must tell your immediate family. You must tell your relatives. You must tell your friends if indeed they are your friends. You must tell the people you work with. You must tell the people in the stores you shop in. Once they realize that we are indeed their children, that we are indeed everywhere, every myth, every lie, every innuendo will be destroyed once and all. And once you do, you will feel so much better.”

Del was pissed when I admitted I wasn’t out on the job.“What!” She exclaimed. “You’re still in the closet at work! Don’t you see why it’s important for us all to be out? How can you leave me hanging out there on a limb? I almost lost my job!”

She had a good point—several good points. I thought about why I’d stayed closeted. It was easier. I didn’t want to risk the wrath and disdain of my co-workers. They weren’t really interested in my private life and I couldn’t care less about theirs. It was hard enough just being the only female on the job. You imagine the worst thing that could happen. They wouldn’t physically attack me. But they could refuse to work with me just as one white guy in the machine shop had refused to work with a Black guy. They could refuse to talk to me, a trick men used on women all the time to get them to quit. They could fire me. I’d been hired on as a temporary worker with no employment rights. I wasn’t safe.

But I promised my lover I would come out.

My electric “shop” was a windowless closet next to the machine shop office where my boss, Manuel, and a secretary worked. They were always trying to get me to fill in when she was out sick, which happened with regularity. I had made the mistake of answering truthfully when they’d asked if I could type. I’d refused and I hadn’t relented even when Dave, the auto shop foreman cried crocodile tears as he tried to type with hands missing several of their fingers. Somehow the guy was still able to work on trucks. But that was men’s work.

One day Manuel made a reference to my husband. That was my opening. I hadn’t had to wait long.

“I don’t have a husband,” I said. “I’m gay.”

When you come out to them, men are either totally shocked or they tell you they knew all along. Manuel was shocked, but he recovered quickly.

I didn’t have to tell anyone else. Word got around the yard. I heard one of the machinists, a religious nut, had moved me into the hated category. But he was someone I could avoid.

Bobby was cool. “I knew it,” he said.

Read more about the Tradeswoman experience in San Francisco: