Tradeswomen Magazine Documents Two Decades of Activism: Difference between revisions

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) (added abstract based on visiting Bolerium Books) |

m (Protected "Tradeswomen Magazine Documents Two Decades of Activism" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite))) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 15:24, 8 August 2024

"I was there..."

by Molly Martin, 2022, originally published on tradeswomn blog

Early "Non-Traditional Employment for Women" Demonstration, 1970s.

Photo: Molly Martin

| Tradeswomen Magazine is the first and only national magazine written by and for women in the skilled trades. Molly Martin and Tradeswomen, Inc. produced the publication for nearly two decades, highlighting the written experiences of blue-collar women. The magazine included a variety of content, including how-to guides, poetry, short stories, and photography in addition to information about resources for these women to draw on. |

Before there were Facebook groups, there was Tradeswomen Magazine.

Published quarterly from 1981 until 1999, Tradeswomen Magazine gave voice to a community of women all over the country and the world who were isolated and often harassed at work. We were pioneers, we had stories to tell, and the only people who truly understood our struggles were other women doing the same work.

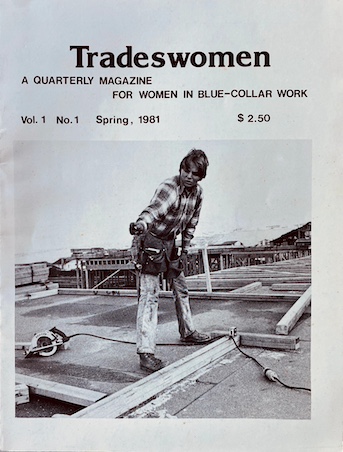

Our first issue of Tradeswomen Magazine, Spring 1981.

Tradeswomen Magazine documents an important period in our collective history, of a time when we were just starting to break down the barriers to nontraditional jobs, a time when we had to fight to be hired, and a time when every day on the job put us at the cutting edge of the feminist movement.

We wrote about sexual harassment, racism in construction, affirmative action, trades training programs, health and safety, union apprenticeships, and we interviewed women about what it was like working in their trades.

Unfortunately, tradeswomen still struggle with many of the same issues we wrote about and discussed in the 1980s and 90s. That makes Tradeswomen Magazine not just an historic artifact, but also still relevant to the tradeswomen of the 21st century.

In the 1970s Tradeswomen in the San Francisco Bay Area had been communicating through a mimeographed newsletter. In 1979 we founded the nonprofit Tradeswomen Inc. Then in 1980 the organization received a small grant from the U.S. Department of Labor with the help of Madeline Mixer, regional director of the Department’s Women’s Bureau. The grant allowed us to print and mail out two issues of a publication to individual tradeswomen and organizations across the country. After that, we depended on subscriptions along with volunteer labor to sustain the magazine.

We organized as a collective, usually with one of the collective members taking the position of executive editor. We did not operate by consensus–somebody needed to have the last word. The first editor, carpenter Jeanne Tetrault, had edited a newsletter and a book about country women. Jeanne convinced us that the publication should be a magazine and not a newsletter. People throw away newsletters, she said, but they keep magazines. This proved true. Over the years we’ve been contacted by many tradeswomen who saved all the issues and wanted to make sure we had copies of them all for the archives.

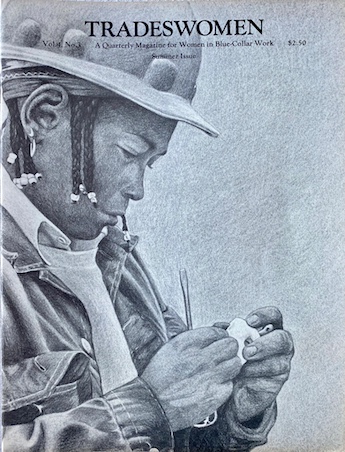

Tradeswomen Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 3, Summer 1984.

Eleven women composed our first collective. In the early years we met on a Saturday and typed our stories into columns, then cut them out and pasted them onto mock-up boards. The photographs were sent to a camera shop to be made into halftones for printing. After we picked up the magazine from the (union) printer, we sponsored a mailing party in which volunteers stuck a mailing label on each magazine, then bundled them into zip code bunches for bulk mailing. It was quite a cumbersome task given that we sent out about a thousand magazines quarterly. The mailing parties continued through the very last issue.

Over the two decades, hundreds of women participated in the publication of the magazine. It really was a community-based effort. Tradeswomen Inc.’s staff person took care of memberships, subscriptions and finances.

From the very first issue, carpenter Sandy Thacker, whose photograph graces its cover, provided photos. We agreed that these images of women on the job were as important, if not more important, than our words. Anne Meredith and others also supplied photos. From the beginning we made an effort to feature photos of women of color.

Executive editor was a burn-out job. After the first year, Jeanne Tetrault bowed out as editor, and cabinetmaker Sandra Marilyn and dock worker Joss Eldredge assumed editorial control. From 1982 to 1987 with the help of volunteers as well as Tradeswomen Inc. directors Bobbie Kierstead and then Sue Doro, Joss and Sandra produced 20 memorable issues.

Then a collective reemerged with carpenter Barb Ryerson as editor. We began exploring digitization. I took on the job of editor in 1988 and was joined by electrician Helen Vozenilek in 1989. Along with a bevy of contributors, Helen and I produced nine issues before we burned out. Then electrician Janet Scoll Johnson assumed the helm to publish 10 beautiful issues as we went to color covers. When Janet burned out, the Tradeswomen Inc. director, Bobbi Tracy picked up the slack, with C.J. Thompson-White producing two issues.

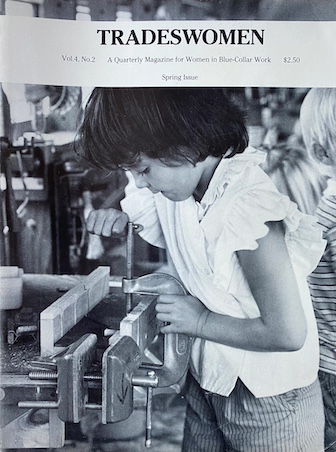

Tradeswomen Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 2, Spring 1984.

During this period Tradeswomen Inc. also had been publishing a local monthly newsletter, Trade Trax, to inform women in the local Bay Area about job openings and more timely events. We decided to roll the magazine and newsletter into one publication coming out six times a year instead of quarterly. I took the role of editor, tacking a calendar of the whole year on my wall to remind me of deadlines. It seemed like every day was a deadline! After producing five issues, I had to admit it was too much work to pile on my 40-hour work week as an electrical inspector.

We returned to publishing the magazine as a quarterly in 1996. I bought a roll-top desk set up for a computer, assembled it in my bedroom and called it my International Publishing Empire. I edited each issue and laid it out in a computer program called PageMaker, whose workings I understood just enough to get by. Many folks helped in the magazine’s last years, but the most devoted was Bob Jolly, a retired English teacher whose daughter had been a tradeswoman. Finally, in the 1998-99 winter issue, I wrote of my intention to pass on the job to another volunteer editor. No one applied for the job, and that became the final issue.

We saved all the issues of Tradeswomen Magazine with the intention of making them available online. Retired stationary engineer Pat Williams volunteered hundreds of hours of her time to digitize every issue. Thanks to Pat and every one of the volunteers who helped to make this publication a written piece of our history. The magazine can now be found in the California State University at Dominguez Hills Tradeswomen Archives. Actual copies of the whole set are available at the Tradeswomen Archives, the San Francisco Labor Archives and Research Center, and the San Francisco Public Library.

Tradeswomen Magazine was the first and only national publication written, edited and published by and about women in trades. I’m so proud to have been a part of its creation.