Highway 101: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) m (Replaced links with hyperlinks) |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | |||

''by Eva Knowles, 2024'' | |||

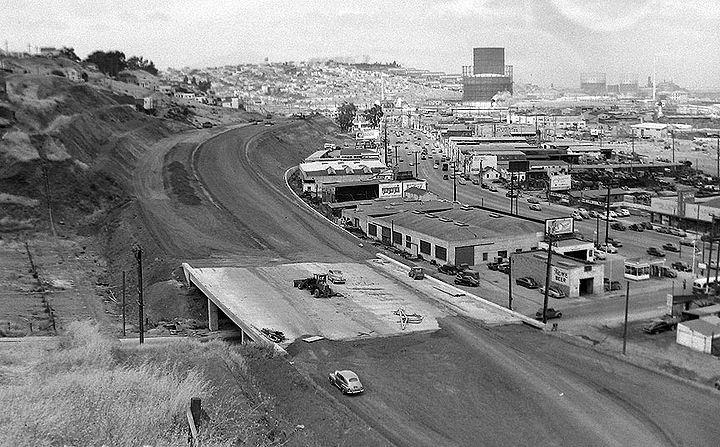

[[Image:Brady-Hwy-101-construction-1955ish-aerial.jpg]] | |||

'''Aerial view of mid-1950s construction of Highway 101, before it was connected to the Bay Bridge.''' | |||

''Photo: Ed Brady'' | |||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" | '''The creation of the portion of Highway 101 that traverses San Francisco began as early as the 1920s with the construction of the Bayshore Highway, which would be replaced with the Bayshore Freeway in the 1950s. The freeway marked a massive development in urban transportation but also significantly disrupted the communities already living in the areas in which it was built. Its history and present effects represent both a social justice and environmental justice issue that the city has yet to solve.''' | |||

|} | |||

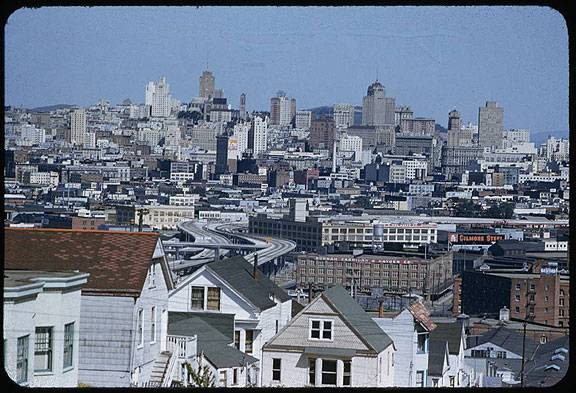

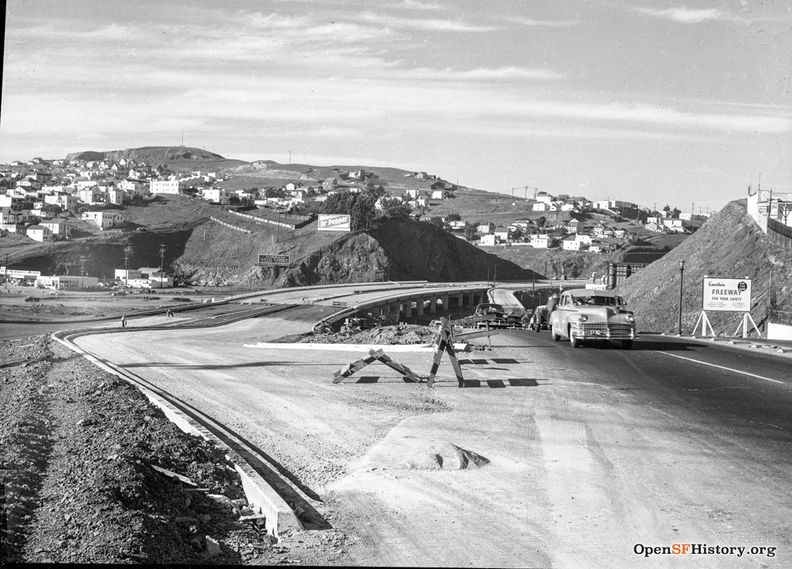

[[Image:Cushman-April-10-1955-20th-and-Rhode-Island-towards-Nob-Hill-P07970.jpg]] | |||

'''View northward from 20th and Rhode Island on Potrero Hill, Hwy 101 in center of image, April 10, 1955.''' | |||

''Photo:'' [http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/cushman/ ''Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P07970)''] | |||

'''Bayshore Highway to Bayshore Freeway''' | |||

In the early twentieth century, as San Francisco and San Jose grew rapidly, the limitations of the aging El Camino Real became increasingly apparent. At the time, those who wanted to travel from San Francisco to San Jose and vice versa took El Camino Real. As automobile traffic increased, the two-lane road quickly proved insufficient and prompted the conception of a new highway. Construction on what came to be named the Bayshore Highway began on September 11, 1924, which Mayor Rolph declared to be “Bayshore Highway Day.” During these same years, following his grand plans of annexing towns on the peninsula to the south, Mayor Rolph also oversaw the widening of the Bernal Cut to expand San Jose Avenue to a double track steam railway and four lanes of car traffic. | |||

The highway was initially funded by the City of San Francisco and constructed in increments, which, when proven successful, garnered additional funding from the state. Though dedicated in 1929, it wasn’t fully completed until June 12, 1937. The newly completed Bayshore Highway was then given the designation of U.S. Route 101—a designation that El Camino Real had held previously, prompting an uproar from El Camino businesses. They were successful, gaining the designation back, while the Bayshore Highway became the bypass. | |||

Within only a few years, the Bayshore Highway had gained a nickname: “Bloody Bayshore,” for its having twice the accidents of the average California highway. In 1940, the California Highways and Public Works proposed converting what was at that point a four-lane highway with only a painted yellow line in the middle to freeway standards, which entailed a median and separation from surface streets. Construction on the Bayshore Freeway began in 1950 and the first unit, from Augusta Street to 25th Street, opened to public use in 1951. | |||

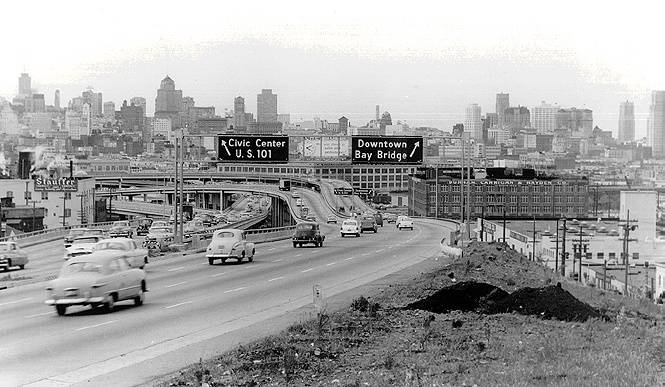

[[Image:transit1$james-lick-freeway-1957.jpg]] | [[Image:transit1$james-lick-freeway-1957.jpg]] | ||

'''The James Lick Freeway (Highway 101) in 1957, northbound, just past Vermont St. exit off Potrero Hill.''' | '''The James Lick Freeway (Highway 101) in 1957, northbound, just past Vermont St. exit off Potrero Hill.''' | ||

[[Image: | That same year, the California state legislature renamed the portion of the Bayshore Freeway within San Francisco after James Lick, a prominent California philanthropist. Lick, who was by some estimates the wealthiest man in California at the time of his death, had acquired large swaths of land during the Gold Rush. He left his estate to scientific and social causes, including San Jose’s Lick Observatory and San Francisco’s Lick-Wilmerding High School. | ||

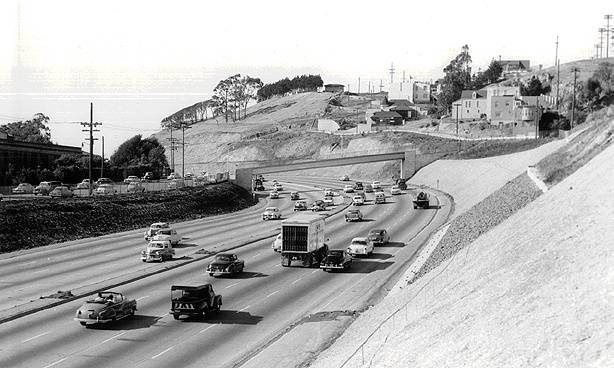

[[Image:pothill$hwy-101-1957.jpg]] | |||

'''The James Lick Freeway (Highway 101) in 1957, northbound from 23rd Street overpass.''' | '''The James Lick Freeway (Highway 101) in 1957, northbound from 23rd Street overpass.''' | ||

''Photos: San Francisco History | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | ||

After 1951, the freeway would open in sections. The San Francisco skyway to the Bay Bridge opened in 1955. The portion of the freeway within San Francisco was completed in 1958 and was finished through San Jose by 1962. In 1963, the Bayshore Freeway became the mainline highway once more, replacing El Camino Real. The original Bayshore Highway, now called Bayshore Boulevard, now runs parallel to U.S. 101. | |||

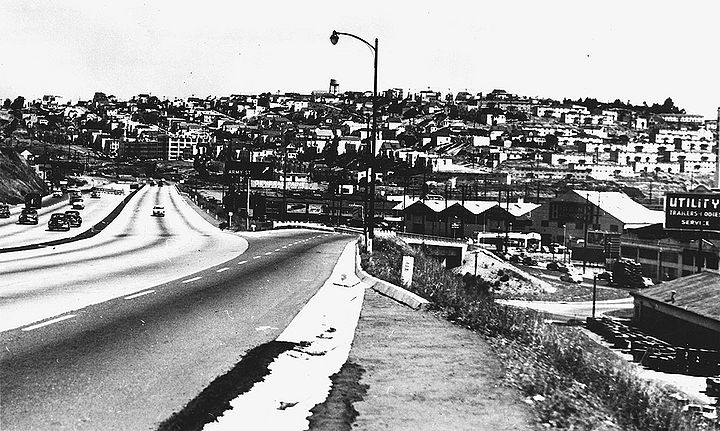

[[Image:Bayshore-Freeway-north-at-Army-St-offramp-freeway-ends-ahead-1956.jpg|720px]] | |||

'''Bayshore freeway north at Army Street offramp, 1956. The 101 freeway is still unfinished in distance.''' | |||

''Photo: C.R. Collection'' | |||

[[Image:Building-hwy-101-at-edge-of-Bernal-Heights-and-Cortland-1955 6750.jpg|720px]] | |||

'''Building Highway 101 where it crosses Cortland Avenue alongside Bernal Heights, 1955.''' | |||

''Photo: Private Collector'' | |||

'''Community Impact''' | |||

Upon its completion, there was widespread excitement and a quick jump in use. However, not everyone was happy with the new freeway. Six-foot-tall fences alongside much of the freeway meant that people who lived nearby could no longer cross the road and that buses no longer stopped there. This was clearly in the interest of safety given the high speeds of traveling automobiles, but the concept of freeways was relatively new and took some time to get accustomed to. | |||

Highway 101 was San Francisco’s first freeway, and would remain one of the only despite the efforts of the California Division of Highways. In the 1950s, the California Division of Highways developed a plan to build freeways all over San Francisco and were ultimately stopped through strong citizen opposition in what is now referred to as the Freeway Revolt. | |||

[[Image:US101 Freeway construction circa 1953 north to Bernal Hts wnp28.1050.jpg|792px]] | |||

'''Highway 101 construction, 1953, off southeast end of Bernal Heights, near the later intersection with I-280.''' | |||

''Photo: OpenSFHistory.org / wnp28.1050'' | |||

Freeway construction also largely occurred hand in hand with urban renewal projects as a supposed solution to urban blight. Much of the land seized through eminent domain under mid-20th century urban renewal policies was in fact used for freeway construction. These “blighted” areas were disproportionately home to low-income people and people of color. They were often quite similar to the areas that back in the late 1930s had been given the redlining grades of “declining” and “hazardous” based on the race, class, and ethnicity of those who lived there. This history is not exclusive to San Francisco, but certainly rings true here—Highway 101 passes through the eastern side of San Francisco, which compared to its middle and western areas was disproportionately subjected to both poor redlining grades and urban renewal. According to a 2023 study, “neighborhoods with a higher percentage of Black persons, laborers, lower educational attainment, and people living in dense housing were associated with freeway placement” (1). These socially vulnerable communities rarely had decision-making power at the city level, making it easier to take their land than more affluent communities elsewhere in the city. | |||

[[Image:Hwy-101-at-Army-w-Potrero-Hill-under-construction-1955 6748.jpg|720px]] | |||

'''Highway 101 at Army under construction, 1955, with Potrero Hill in background.''' | |||

''Photo: Private Collector'' | |||

The construction of Highway 101 dealt a lasting blow to these neighborhoods. The freeway tore through communities, displacing people and requiring that homes and businesses were razed to make room for it. This damaged not only a sense of community in neighborhoods like SoMa and the Mission District but also neighborhood commercial sectors, further impoverishing these areas. At the same time, these impacted areas also experienced poorer air quality from automobile emissions, making the issue of freeways one of environmental justice as well. The San Francisco Planning Department has designated Environmental Justice Communities throughout the city, defined as “the areas facing the top one-third of cumulative environmental and socioeconomic burdens across the City” (2). Nearly all of these communities are located along freeway corridors, and many of them along Highway 101. | |||

[[Image:24VMT930.jpg]] | |||

'''In 1930 the Dutch Boy Paint Factory sat on the northeast corner of 24th and Kansas (above). By 1994 the west side of Kansas Street had been demolished and replaced by the 101 Freeway, hidden by eucalyptus trees in this image, and a new apartment building had replaced the paint factory (below).''' | |||

[[Image:24VMT993.jpg]] | |||

''Photos: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library (AAB-5992) (1930) and David Green (1994)'' | |||

The evolution of the Bayshore Freeway represents more than just a shift in infrastructure; it encapsulates the broader social and environmental impacts of urban planning during the mid-twentieth century. While the freeway system promised increased efficiency and connectivity, it also brought significant challenges. The displacement of communities, particularly those already marginalized, and the environmental burdens faced by neighborhoods along Highway 101 highlight the often overlooked consequences of such developments. | |||

[[Image:Hwy-101-heavy-traffic-at-Vermont-St-exit-northerly 4019.jpg]] | |||

'''Highway 101 full of autos in 2014.''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | |||

[[Image:Hospital-Curve-heavy-traffic-hwy-101-w-Bernal-behind 4020.jpg]] | |||

'''Hospital Curve southbound, Highway 101, with Bernal Heights.''' | |||

''Photo: Chris Carlsson'' | |||

'''Notes''' | |||

1. Roth, Johanna. [https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/7b3d5f8acf134b66b5ef5bf5ff3bf625 “Equity-Based History of San Francisco’s Freeways.”] ArcGIS StoryMaps, May 31, 2023. | |||

2. [https://sfplanning.org/project/environmental-justice-framework-and-general-plan-policies “Environmental Justice Framework and General Plan Policies.”] Environmental Justice Framework and General Plan Policies | SF Planning. Accessed August 5, 2024. | |||

[[Freeways trashed by 89 quake |Prev. Document]] [[Hidden Class Politics of Transit |Next Document]] | [[Freeways trashed by 89 quake |Prev. Document]] [[Hidden Class Politics of Transit |Next Document]] | ||

[[category:Transit]] [[category:1950s]] | [[category:Transit]] [[category:Redevelopment]] [[category:Potrero Hill]] [[category:Mission]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:SOMA]] [[category:1920s]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:1990s]] [[category:2010s]] | ||

Latest revision as of 09:39, 13 August 2024

Historical Essay

by Eva Knowles, 2024

Aerial view of mid-1950s construction of Highway 101, before it was connected to the Bay Bridge.

Photo: Ed Brady

| The creation of the portion of Highway 101 that traverses San Francisco began as early as the 1920s with the construction of the Bayshore Highway, which would be replaced with the Bayshore Freeway in the 1950s. The freeway marked a massive development in urban transportation but also significantly disrupted the communities already living in the areas in which it was built. Its history and present effects represent both a social justice and environmental justice issue that the city has yet to solve. |

View northward from 20th and Rhode Island on Potrero Hill, Hwy 101 in center of image, April 10, 1955.

Photo: Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P07970)

Bayshore Highway to Bayshore Freeway

In the early twentieth century, as San Francisco and San Jose grew rapidly, the limitations of the aging El Camino Real became increasingly apparent. At the time, those who wanted to travel from San Francisco to San Jose and vice versa took El Camino Real. As automobile traffic increased, the two-lane road quickly proved insufficient and prompted the conception of a new highway. Construction on what came to be named the Bayshore Highway began on September 11, 1924, which Mayor Rolph declared to be “Bayshore Highway Day.” During these same years, following his grand plans of annexing towns on the peninsula to the south, Mayor Rolph also oversaw the widening of the Bernal Cut to expand San Jose Avenue to a double track steam railway and four lanes of car traffic.

The highway was initially funded by the City of San Francisco and constructed in increments, which, when proven successful, garnered additional funding from the state. Though dedicated in 1929, it wasn’t fully completed until June 12, 1937. The newly completed Bayshore Highway was then given the designation of U.S. Route 101—a designation that El Camino Real had held previously, prompting an uproar from El Camino businesses. They were successful, gaining the designation back, while the Bayshore Highway became the bypass.

Within only a few years, the Bayshore Highway had gained a nickname: “Bloody Bayshore,” for its having twice the accidents of the average California highway. In 1940, the California Highways and Public Works proposed converting what was at that point a four-lane highway with only a painted yellow line in the middle to freeway standards, which entailed a median and separation from surface streets. Construction on the Bayshore Freeway began in 1950 and the first unit, from Augusta Street to 25th Street, opened to public use in 1951.

The James Lick Freeway (Highway 101) in 1957, northbound, just past Vermont St. exit off Potrero Hill.

That same year, the California state legislature renamed the portion of the Bayshore Freeway within San Francisco after James Lick, a prominent California philanthropist. Lick, who was by some estimates the wealthiest man in California at the time of his death, had acquired large swaths of land during the Gold Rush. He left his estate to scientific and social causes, including San Jose’s Lick Observatory and San Francisco’s Lick-Wilmerding High School.

The James Lick Freeway (Highway 101) in 1957, northbound from 23rd Street overpass.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

After 1951, the freeway would open in sections. The San Francisco skyway to the Bay Bridge opened in 1955. The portion of the freeway within San Francisco was completed in 1958 and was finished through San Jose by 1962. In 1963, the Bayshore Freeway became the mainline highway once more, replacing El Camino Real. The original Bayshore Highway, now called Bayshore Boulevard, now runs parallel to U.S. 101.

Bayshore freeway north at Army Street offramp, 1956. The 101 freeway is still unfinished in distance.

Photo: C.R. Collection

Building Highway 101 where it crosses Cortland Avenue alongside Bernal Heights, 1955.

Photo: Private Collector

Community Impact

Upon its completion, there was widespread excitement and a quick jump in use. However, not everyone was happy with the new freeway. Six-foot-tall fences alongside much of the freeway meant that people who lived nearby could no longer cross the road and that buses no longer stopped there. This was clearly in the interest of safety given the high speeds of traveling automobiles, but the concept of freeways was relatively new and took some time to get accustomed to.

Highway 101 was San Francisco’s first freeway, and would remain one of the only despite the efforts of the California Division of Highways. In the 1950s, the California Division of Highways developed a plan to build freeways all over San Francisco and were ultimately stopped through strong citizen opposition in what is now referred to as the Freeway Revolt.

Highway 101 construction, 1953, off southeast end of Bernal Heights, near the later intersection with I-280.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org / wnp28.1050

Freeway construction also largely occurred hand in hand with urban renewal projects as a supposed solution to urban blight. Much of the land seized through eminent domain under mid-20th century urban renewal policies was in fact used for freeway construction. These “blighted” areas were disproportionately home to low-income people and people of color. They were often quite similar to the areas that back in the late 1930s had been given the redlining grades of “declining” and “hazardous” based on the race, class, and ethnicity of those who lived there. This history is not exclusive to San Francisco, but certainly rings true here—Highway 101 passes through the eastern side of San Francisco, which compared to its middle and western areas was disproportionately subjected to both poor redlining grades and urban renewal. According to a 2023 study, “neighborhoods with a higher percentage of Black persons, laborers, lower educational attainment, and people living in dense housing were associated with freeway placement” (1). These socially vulnerable communities rarely had decision-making power at the city level, making it easier to take their land than more affluent communities elsewhere in the city.

Highway 101 at Army under construction, 1955, with Potrero Hill in background.

Photo: Private Collector

The construction of Highway 101 dealt a lasting blow to these neighborhoods. The freeway tore through communities, displacing people and requiring that homes and businesses were razed to make room for it. This damaged not only a sense of community in neighborhoods like SoMa and the Mission District but also neighborhood commercial sectors, further impoverishing these areas. At the same time, these impacted areas also experienced poorer air quality from automobile emissions, making the issue of freeways one of environmental justice as well. The San Francisco Planning Department has designated Environmental Justice Communities throughout the city, defined as “the areas facing the top one-third of cumulative environmental and socioeconomic burdens across the City” (2). Nearly all of these communities are located along freeway corridors, and many of them along Highway 101.

In 1930 the Dutch Boy Paint Factory sat on the northeast corner of 24th and Kansas (above). By 1994 the west side of Kansas Street had been demolished and replaced by the 101 Freeway, hidden by eucalyptus trees in this image, and a new apartment building had replaced the paint factory (below).

Photos: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library (AAB-5992) (1930) and David Green (1994)

The evolution of the Bayshore Freeway represents more than just a shift in infrastructure; it encapsulates the broader social and environmental impacts of urban planning during the mid-twentieth century. While the freeway system promised increased efficiency and connectivity, it also brought significant challenges. The displacement of communities, particularly those already marginalized, and the environmental burdens faced by neighborhoods along Highway 101 highlight the often overlooked consequences of such developments.

Highway 101 full of autos in 2014.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Hospital Curve southbound, Highway 101, with Bernal Heights.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Notes

1. Roth, Johanna. “Equity-Based History of San Francisco’s Freeways.” ArcGIS StoryMaps, May 31, 2023.

2. “Environmental Justice Framework and General Plan Policies.” Environmental Justice Framework and General Plan Policies | SF Planning. Accessed August 5, 2024.