Miriam Dinkin Johnson: Difference between revisions

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) (part of Molly labor series) |

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

2. Johnson, Miriam. “Employment Service Revisited,” in ''Of Heart and Mind: Social Policy Essays in Honor of Sar A. Levitan'', eds. Garth Mangum and Stephen Mangum. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1996. | 2. Johnson, Miriam. “Employment Service Revisited,” in ''Of Heart and Mind: Social Policy Essays in Honor of Sar A. Levitan'', eds. Garth Mangum and Stephen Mangum. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1996. | ||

''Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists [[Making the Hill Red: Bernal Labor Activists|here]]. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects.'' | |||

[[category:Labor]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:Women]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:1960s]] | [[category:Labor]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:Women]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:1960s]] | ||

Revision as of 12:36, 5 September 2024

Historical Essay

by Molly Martin, Gail Sansbury, Elaine Elison, and the Bernal History Project

Miriam Dinkin Johnson, 1918-2001.

Photo courtesy of the Bancroft Library and UC Berkeley

| Bernal Heights has been a center of labor activism for over a century; many prominent labor organizers can be traced there. This profile is part of a series put together by the Bernal History Project for Labor Fest in 2008 that tells the stories of six “reds” from Bernal Heights: Miriam Dinkin Johnson, Eugene Paton, Phiz Mezey, Dow Wilson, Bill Sorro, and Giuliana Milanese. |

Miriam Johnson was born Miriam Dinkin in Chicago. Her family moved first to Los Angeles and then to San Francisco by the early 1930s. Her parents were Jewish immigrants from Russia, and like she herself would become, were labor and political activists.

She was politically active by the time she was a teenager. She was on a Writer’s Project under the Works Progress Administration in 1935, then began working for the WPA-supported Union Recreation Center, a joint project of San Francisco maritime unions.

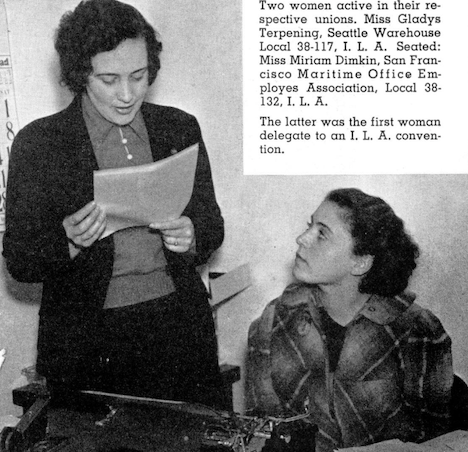

Gladys Terpening and Miriam Dinkin [Johnson] (right).

Photo courtesy of LARC, SFSU

When the Pacific Coast Maritime Strike broke out in 1936, the Union Recreation Center served as its headquarters. The strike was an effort by shipowners to destroy waterfront unions in response to the creation of the Marine Federation of the Pacific. Famous labor leader Harry Bridges led efforts to form the federation after rising to prominence in the 1934 General Strike. Johnson helped form the Marine Office Employees Association and became its secretary-treasurer. She was the first woman delegate to attend an International Longshoremen’s Association convention. At this time, Johnson was only eighteen years old.

It was also through the Union Recreation Center that in 1938 Johnson was introduced to the King-Ramsay-Conner Defense Committee and got a job as a secretary. She was soon promoted to executive secretary, taking control of the committee with head Z.R. Brown.

Ernest Ramsay, Frank J. Connor and Earl King at their 3 month trial, 1936-37.

Photo courtesy of the Bancroft Library and UC Berkeley

The defense committee formed in response to a historic labor case in which three union leaders—Earl King, Ernest Ramsay, and Frank J. Conner—were accused of murder. In March of 1936, chief engineer George Alberts was brutally murdered aboard the Point Lobos off of Alameda. The three men, as well as one other, were arrested despite their not being onboard the ship at the time. They did, however, all hold positions in the Marine Firemen, Oilers, Water Tenders and Wipers Association (MFOW), a small union based in San Francisco that worked closely with Harry Bridges and the Maritime Federation. The men were convicted and sentenced to twenty years at San Quentin Prison. The trial coincided with the 1936-1937 West Coast maritime strike, and it didn’t take long for other labor activists to identify the case as a frame-up intended to discredit the waterfront unions and form a defense committee.

Though young, Johnson was able to win the trust of the three men. In an interview, Johnson explained it this way: “The first job they gave me, the tacit agreement that I made with Ramsay, and with all of them, then, was that they were my boss and no one else. And that was the way it stayed right until the very end… I would do nothing without their [King's, Ramsay's, and Conner's] approval, and make no decisions — that I belonged to them, that I was their agent, that I acted on their behalf. That was the first agreement, the first time that they felt they could deal with me, especially Ramsay” (1). Johnson remained committed to the mens’ freedom for the next several years, and was successful: the men were paroled on November 28, 1941.

Johnson later worked for the State Employment Service, from 1953 through the 1970s. She worked to end racial profiling within the Employment Service, then occurring under the guise of using one’s residence, as well as to provide wide access to job listings. In 1962 she was appointed to the post of Statewide Minority Specialist by Governor Pat Brown. In an essay, she wrote, “I remember thinking then that my most pressing task was to stop the interviewers’ fingers as they rummaged through the applicant file box – to stop them from automatically bypassing a suspected nonwhite applicant and actually to make that referral, whatever the consequences” (2). In 1973, she would publish Counter Point: The Changing Employment Service, an evaluation of the Employment Service.

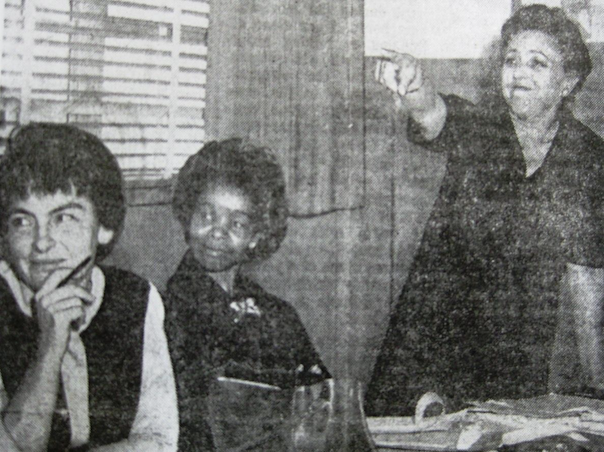

Left to right: Ruth Maguire, Ruby Shaw, and Miriam Johnson, “temporary officers” of Mothers Alone Working (MAW).

Photo courtesy of the Booker T. Washington Center, San Francisco.

The sixties also marked the birth of another initiative: Miriam Johnson was a founding member of Mothers Alone Working (MAW), a self-help organization demanding programs to aid low-income working mothers. MAW held its first public meeting on November 7, 1965. After three meetings, 300 women had signed up.

Despite being named one of “Ten Outstanding Projects” by the San Francisco Chronicle, MAW struggled with funding from the beginning. They submitted proposals to the San Francisco Foundation and the Office of Economic Opportunity to no avail. In the words of co-founder Ruth Maguire, “Everybody loved us. But nobody would give us a dime!” Meanwhile, Johnson and other members including Maguire were working fifteen-hour-a-day jobs.

MAW died soon after, but no one would call it a complete loss. Said co-founder Madeline Mixer in a 1998 Labor Archives and Research Center interview:

“One fact that became apparent was the interest of hundreds of women in such an organization. Even though it was not destined to last a long time, it did give some solace to women who were living in a world that denied that there were mothers alone who had all the needs of every other type of family and little support for those needs. I think that many a woman took comfort knowing that she was not the only one.”

Johnson went on to become a respected labor market researcher and writer. She remained persistent throughout her life: she took up walking later in life and once walked about fifty miles from San Francisco to Marin. She died in 2001.

Notes

1. Johnson, Miriam. “The King-Ramsay-Conner Defense Committee, 1938-1941.” Interview by Miriam Feingold Stein. Earl Warren Oral History Project. Regional Oral History Office, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley.

2. Johnson, Miriam. “Employment Service Revisited,” in Of Heart and Mind: Social Policy Essays in Honor of Sar A. Levitan, eds. Garth Mangum and Stephen Mangum. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 1996.

Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists here. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects.