Phiz Mezey: Difference between revisions

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) (part of Molly labor series) |

(added category) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

Mezey was the youngest journalism professor at San Francisco State at just twenty-three years old. The hiring committee was at first hesitant about her ability to lead a class of men returning from war. However, she was clearly talented: her stories had already been published in the ''New Republic'', the ''New York Times'' and ''The Nation''. | Mezey was the youngest journalism professor at San Francisco State at just twenty-three years old. The hiring committee was at first hesitant about her ability to lead a class of men returning from war. However, she was clearly talented: her stories had already been published in the ''New Republic'', the ''New York Times'' and ''The Nation''. | ||

In their book, ''Wherever There’s a Fight'', Elaine Elison and Stan Yogi tell the story of how Truman-era loyalty oaths were forced onto university employees; much of this profile is drawn from their work. Beginning in June 1949, all University of California employees had to sign an oath denying Communist Party membership. In February 1950, UC regents voted to fire all employees who did not sign by April 30, and sure enough on August 25, thirty-one faculty members were fired. These loyalty oaths would not remain unique to the UC system but find their way to Mezey at SF State. | In their book, ''Wherever There’s a Fight'', Elaine Elison and Stan Yogi tell the story of how Truman-era loyalty oaths were forced onto university employees; much of this profile is drawn from their work. Beginning in June 1949, all University of California employees had to [[UC Berkeley: The Loyalty Oath Controversy, 1949-51|sign an oath denying Communist Party membership]]. In February 1950, UC regents voted to fire all employees who did not sign by April 30, and sure enough on August 25, thirty-one faculty members were fired. These loyalty oaths would not remain unique to the UC system but find their way to Mezey at SF State. | ||

Political trouble with SF State had started earlier that summer for Mezey, when a disgruntled student reported her to administrators and made insinuations to her “Communist leanings”. As part of her job, Mezey was an advisor for the student newspaper, the Golden Gater, for which the student, Arthur Duffy, was a summer session editor. Duffy had refused to run an anti-Korean War article because of his own beliefs despite advice from Mezey and the chief editor to allow multiple perspectives. In part because of this incident and in part because of his poor student performance, Mezey gave the student a failing grade. To administrators, Duffy made the case that he had received the grade because of his political views. | Political trouble with SF State had started earlier that summer for Mezey, when a disgruntled student reported her to administrators and made insinuations to her “Communist leanings”. As part of her job, Mezey was an advisor for the student newspaper, the ''Golden Gater'', for which the student, Arthur Duffy, was a summer session editor. Duffy had refused to run an anti-Korean War article because of his own beliefs despite advice from Mezey and the chief editor to allow multiple perspectives. In part because of this incident and in part because of his poor student performance, Mezey gave the student a failing grade. To administrators, Duffy made the case that he had received the grade because of his political views. | ||

Mezey was instructed by college administrators not only to provide a report of the incident but also to sign an oath denying allegiance to the Communist Party. Mezey refused, writing in a letter to SF State president J. Paul Leonard: “I will not sign the loyalty oath now because I know that hereafter no teacher can adequately be protected under the law.” A month later, she was fired under the Levering Act, along with eight others who had also refused to sign. | Mezey was instructed by college administrators not only to provide a report of the incident but also to sign an oath denying allegiance to the Communist Party. Mezey refused, writing in a letter to SF State president J. Paul Leonard: “I will not sign the loyalty oath now because I know that hereafter no teacher can adequately be protected under the law.” A month later, she was fired under the Levering Act, along with eight others who had also refused to sign. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

''Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists [[Making the Hill Red: Bernal Labor Activists|here]]. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects.'' | ''Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists [[Making the Hill Red: Bernal Labor Activists|here]]. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects.'' | ||

[[category:Labor]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:Women]] [[category:Photography]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] | [[category:Labor]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:Women]] [[category:Photography]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:Famous characters]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:01, 5 September 2024

Historical Essay

by Molly Martin, Gail Sansbury, Elaine Elison, and the Bernal History Project

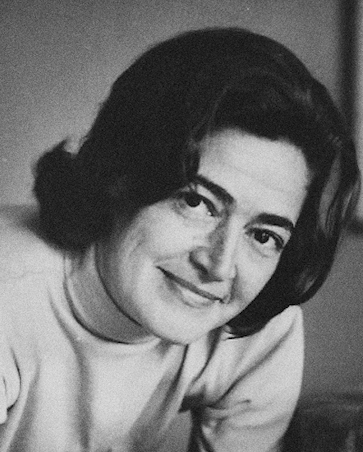

Phiz Mezey, 1925-2020.

| Bernal Heights has been a center of labor activism for over a century; many prominent labor organizers can be traced there. This profile is part of a series put together by the Bernal History Project for Labor Fest in 2008 that tells the stories of six “reds” from Bernal Heights: Miriam Dinkin Johnson, Eugene Paton, Phiz Mezey, Dow Wilson, Bill Sorro, and Giuliana Milanese. |

Originally from New York, Phiz Mezey set out to be a journalist early in her life. She attended Reed College in Oregon and made her way down to San Francisco to pursue a career as a journalist.

Mezey was the youngest journalism professor at San Francisco State at just twenty-three years old. The hiring committee was at first hesitant about her ability to lead a class of men returning from war. However, she was clearly talented: her stories had already been published in the New Republic, the New York Times and The Nation.

In their book, Wherever There’s a Fight, Elaine Elison and Stan Yogi tell the story of how Truman-era loyalty oaths were forced onto university employees; much of this profile is drawn from their work. Beginning in June 1949, all University of California employees had to sign an oath denying Communist Party membership. In February 1950, UC regents voted to fire all employees who did not sign by April 30, and sure enough on August 25, thirty-one faculty members were fired. These loyalty oaths would not remain unique to the UC system but find their way to Mezey at SF State.

Political trouble with SF State had started earlier that summer for Mezey, when a disgruntled student reported her to administrators and made insinuations to her “Communist leanings”. As part of her job, Mezey was an advisor for the student newspaper, the Golden Gater, for which the student, Arthur Duffy, was a summer session editor. Duffy had refused to run an anti-Korean War article because of his own beliefs despite advice from Mezey and the chief editor to allow multiple perspectives. In part because of this incident and in part because of his poor student performance, Mezey gave the student a failing grade. To administrators, Duffy made the case that he had received the grade because of his political views.

Mezey was instructed by college administrators not only to provide a report of the incident but also to sign an oath denying allegiance to the Communist Party. Mezey refused, writing in a letter to SF State president J. Paul Leonard: “I will not sign the loyalty oath now because I know that hereafter no teacher can adequately be protected under the law.” A month later, she was fired under the Levering Act, along with eight others who had also refused to sign.

This was the height of McCarthyism: the Levering Act required all California State employees to sign a loyalty oath by November 2, 1950, or else lose their jobs. Legislation containing the oath was written by Assemblyman Harold A. Levering. All but one legislator voted for the bill. The oath itself, devised during the UC controversy, read:

“I swear that

- I am not a member

- within 5 years of taking this oath I have not been a member

- I will not become a member

of any party or organizations, political or otherwise, that now advocates the overthrow of the Government of the United States or the State of California by force or violence or other unlawful means.”

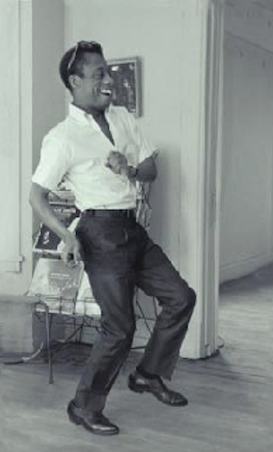

Martin Luther King, Jr., by Phiz Mezey in 1961.

James Baldwin, by Phiz Mezey in 1963.

Mezey got a job at the Koret of California manufacturing plant, and was even promoted to production manager—that is, until the FBI visited her supervisor and she was fired. Mezey remained under FBI surveillance for fifteen years. The combination of FBI interference with employers and being a single mother made it difficult for Mezey to find work. Eventually, she became a freelance photographer and was very successful: she took portraits of hugely influential figures like Martin Luther King, Jr. and James Baldwin as well as capturing political events in San Francisco. Her work has been shown at photo exhibits around the country including San Francisco’s de Young Museum and Museum of Modern Art.

Photo of the 1968 SFSU strike by Phiz Mezey.

Photo courtesy of LARC, SFSU

The Levering Act was ultimately deemed unconstitutional: in 1967, the California Supreme Court decided it violated the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of association. Then, in 1971, the court ruled that it was unconstitutional to fire teachers for refusing to take the oath.

That same year, Mezey earned her MA and PhD equivalency from SF State. She then taught photography at San Francisco City College in the mid-1970s. In 1978, SF State rehired her in the Educational Technology Department—not in her previous position in the Journalism Department. In 1981, she was promoted to full professor.

Phiz Mezey at her home on Winfield Street.

Photo: Elaine Elinson

Mezey retired from teaching in 1990. She lived on Winfield Street surrounded by a dazzling array of home-grown succulents and photos she had taken that document the key political movements of her times.

Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists here. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects.