Eugene "Pat" Paton: Difference between revisions

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) (part of Molly labor series) |

(added categories) |

||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

''Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists [[Making the Hill Red: Bernal Labor Activists|here]]. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects, especially Patty Paton Cavagnaro and Petrina Caruso Paton for their family albums.'' | ''Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists [[Making the Hill Red: Bernal Labor Activists|here]]. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects, especially Patty Paton Cavagnaro and Petrina Caruso Paton for their family albums.'' | ||

[[category:Labor]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:1950s]] | [[category:Labor]] [[category:Bernal Heights]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:Famous characters]] [[category:ILWU]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:04, 5 September 2024

Historical Essay

by Molly Martin, Gail Sansbury, Elaine Elison, and the Bernal History Project

Eugene "Pat" Paton, 1913-1951.

| Bernal Heights has been a center of labor activism for over a century; many prominent labor organizers can be traced there. This profile is part of a series put together by the Bernal History Project for Labor Fest in 2008 that tells the stories of six “reds” from Bernal Heights: Miriam Dinkin Johnson, Eugene Paton, Phiz Mezey, Dow Wilson, Bill Sorro, and Giuliana Milanese. |

Eugene Paton was the president of the ILWU Union Local 6 from 1938 to 1940 and considered by Sam Kagel, coast arbitrator for the unions and close consultant to Harry Bridges, to be the best negotiator he ever met.

Paton was one of twelve children born to Alice and Alex Paton of San Francisco. Alex worked in Butchertown on the killing floor. Eugene's brothers were strapping Irish lads who grew up to be firefighters, Muni conductors, engineers, and Teamsters. In 1940, when Eugene would have been 27, he and eight of his brothers were still living at home with their mother at 28 Bennington Street. The house is still there—not particularly large. Robert, his brother, remembered saying, "Pray you get in the bed first," otherwise there was no room for you.

Photo of Paton, second from left, in a family scrapbook.

The 1934 General Strike would have a significant impact on his career. On May 9, 1934, the longshoremen went on strike, soon followed by the sailors. Over several months they gained the sympathy of many big unions who voted for the general strike, which began peacefully. It followed the police attack and the shooting of two men on July 5, "Bloody Thursday." Of course, employers brought in strikebreakers, and violence flared in ports up and down the coast. Attacks on suspected communists flared during the strike. The 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike lasted 83 days and led to the unionization of all of the West Coast ports. The New York Times under an editorial headline "The American Way" was jubilant: "What already has been accomplished is sufficient demonstration that Americans will not harbor anarchists, nor tolerate revolutionists, and are still able, as Abraham Lincoln said, to 'keep house.'"

Eugene was active in organizing SF warehouses after the strike, establishing himself as the main organizer of warehouse workers in the city. Once a place got organized, the employer had to sit down and negotiate seriously, or there would be a strike. During the 30s, there were often five or six strikes going on at a time. This was all inspired by the longshoremen's victory in 1934. He and Sam Kagel would go in to mediate and win.

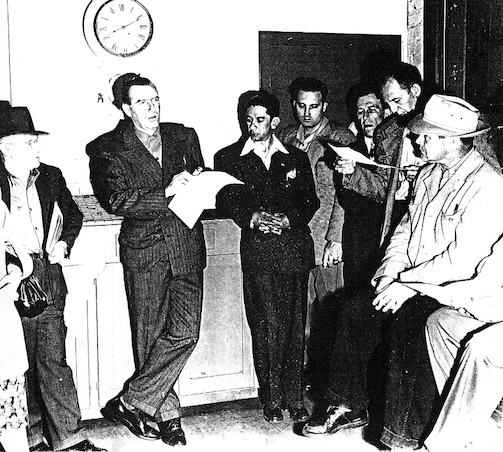

Eugene Paton (right) and Harry Bridges (third from right).

Photo courtesy of LARC, SFSU

Paton had a serious drinking problem, although it never seemed to get in the way of his work. Sam Kagel, a union negotiator for the ILWU, recalls taking him to the offices of a Dr. Goldman, whose nurse would give him a big horse syringe of Vitamin B1 into his backside. Then the men would go downstairs to a restaurant in the same building and Pat would have a steak for breakfast. Both those things restored him to instant health.

In 1938, Paton regularly drank in a bar at the bottom of Sacramento Street on the waterfront with Harry Bridges, Kagel, and a young labor reporter called Katharine Meyer, better known as Katharine Graham, the publisher of Washington Post fame. Katherine and Eugene became friends, and then lovers—the story talks of "the dainty deb and opera first-nighter meets scrappy, hard-living unionist." Eugene was married, and the affair was brief; Katherine returned to Washington, but she never forgot him and mentioned him in her memoirs. Meanwhile, Paton and his wife, Elizabeth, had one son, Raymond Eugene Paton.

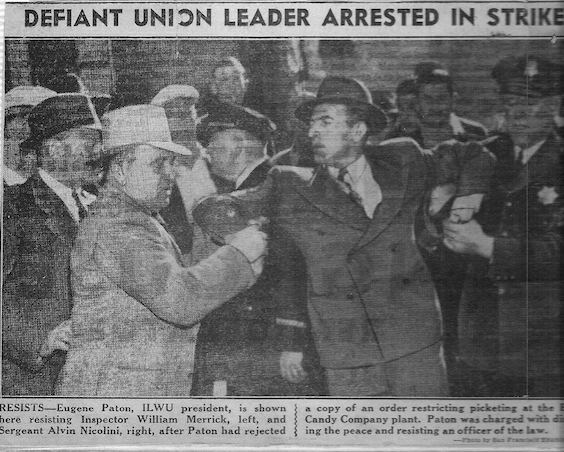

In May 1940, Paton was charged with disturbing the peace at a picket at the Euclid Candy Company plant at 715 Battery. He was slugged by Inspector Sidney Duboce without any provocation, while he was peaceably submitting to arrest.

San Francisco Examiner article about Paton’s 1940 arrest.

In 1940, Paton became the first secretary-treasurer of the ILWU. Three years later, he resigned as secretary-treasurer to enlist. He went into the Army and fought at the Battle of the Bulge; he was promoted on the field from officer to captain.

In 1945, he wrote to the ILWU officers, "This had better be a better world when this is over, because a hell of a lot of swell guys are dying and suffering to make it better. What a debt we owe these guys and their families, and by that I mean really making the world a pleasant place to live in, where poverty, unemployment, discrimination, and all the other self-inflicted curses of mankind are eliminated once and for all.”

Paton’s alcohol problem continued after the war, although he was always able to work. Sam Kagel hoped that his friend and colleague would sober up, but that never happened. In 1951, after he had become an attorney, he recalls Paton asking him for a loan; he gave him $50. The next thing he heard that day was the Examiner noting that Paton had committed suicide by jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge. It was March 22, 1951. "I found out later that he had taken the money and given it to his wife, who was a telephone operator." One newspaper headline blared, "PATON JUMPS OFF GOLDEN GATE."

Harry Bridges delivered the funeral oration at Golden Gate Cemetery in San Bruno, saying, "I knew him as a man of great heart and brave spirit, with tolerance, and sympathetic understanding of the frailties of mankind, especially those frailties that spring from the cruelties and injustices of our social system."

The Ninth Biennial Convention of the ILWU eulogized him a month later, saying he died "a victim of strain and overwork." One newspaper editorial said, "He made the resolve, to hell with everybody, to hell with guys calling other people phony, to hell with all the backbiting and maneuvering, and he took the jump off the bridge. So Eugene Paton went West, a regular guy, a happy-go-lucky guy, a victim of pressure groups. He wasn't the first, and he won't be the last."

The reasons for Paton's suicide are unclear—perhaps he was unstable because of his alcoholism, or because of the pressures of life. He was only 38. There was speculation that his suicide was related to the FBI investigation into Harry Bridges.

Read about other Bernal Heights labor activists here. Thanks to the SF Labor Archives and Research Center, a rich source of information about union movements and working class life in the Bay Area, and the families of our subjects, especially Patty Paton Cavagnaro and Petrina Caruso Paton for their family albums.