Key System and March of Progress: Difference between revisions

(added photos) |

(added photo) |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | ||

''by Michael C. Healy'' | |||

''Text originally published in ''BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System'' Heyday Books: Berkeley CA, 2016'' | |||

[[Image:Key-system-train-on-bay-bridge-from-opening-newspaper.jpg]] | [[Image:Key-system-train-on-bay-bridge-from-opening-newspaper.jpg]] | ||

| Line 17: | Line 21: | ||

''Photographer unknown'' | ''Photographer unknown'' | ||

[[Image:Key-trains-and-bay-bridge-offramps-c-1956-sfmemory.jpg]] | |||

'''Key Trains exiting Bay Bridge, c. 1956.''' | |||

''Photo: SFMemory.org'' | |||

[[Image:Borax 20 mule team.jpg|240px|right]] | |||

The Key System first began operating on October 26, 1903, as the San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose Railway (SFOSJR), founded by Francis Marion “Borax” Smith and a partner, Frank C. Havens. Its primary competitor at the time was the Inter Urban Rail Transit Company (IURT), which began service in the late 1800s and was still a steam operation. IURT was owned by Southern Pacific. Eventually, IURT converted to electricity and became the East Bay Interurban Electric Railway (IER). While it served many of the same areas that SFOSJR had, it eventually ceased operations and sold much of its equipment to SFOSJR long after that operation had been redubbed the Key System. | |||

As part of its transit mix, the SFOSJR owned a fleet of ferries to provide transbay service for commuters to San Francisco. Among them was Borax Smith, who had built a fortune from his namesake cleaning product, Borax. (His company’s logo, the 20 Mule Team wagon, was by then nationally famous.) After settling in Oakland in the late 1800s, he began to think of new enterprises, and he saw an opportunity in the transportation business, although his venture into mass transit had more to do with real estate development than simply wanting to help people move from place to place. Smith and his partner believed that rail transit could support development along its rights-of- way, a natural symbiotic relationship: create the destination and then transport people to it. Perhaps the experience of the transcontinental railroad, where whole towns sprang up along its owned right-of-way, spurred the idea. In other words, the transcontinental railroad was in the real estate business as much as it was in the transportation business. | |||

The parent company of the new electric streetcar system, which had several investors, was in fact called Realty Syndicate. The company acquired large tracts of land in the East Bay and built two hotels, one of which was the famous Claremont, a towering classic white monument from a bygone era that still thrives today as a luxurious resort. | |||

[[Image:Claremont-Hotel city-of-Oakland.jpg]] | |||

'''The Claremont Hotel, built originally by the Realty Syndicate as an anchor for the E-Claremont streetcar line.''' | |||

<iframe src=" | ''Photo: courtesy City of Oakland'' | ||

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/6358_HM_Key_System_ca_1959_01_15_49_00" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | |||

'''Home movies of VS trains on Key System viaduct around Transbay Terminal area; F train along right-of-way in East Bay; Scenes of Bay Area Electric Railroad Association Special (older yellow car) on East Bay streets; North Berkeley tunnel (Shattuck-Solano); downtown Berkeley''' | '''Home movies of VS trains on Key System viaduct around Transbay Terminal area; F train along right-of-way in East Bay; Scenes of Bay Area Electric Railroad Association Special (older yellow car) on East Bay streets; North Berkeley tunnel (Shattuck-Solano); downtown Berkeley''' | ||

| Line 36: | Line 59: | ||

[[Image:Oakmole2.jpg]] | [[Image:Oakmole2.jpg]] | ||

'''The Oakland Mole in early 20th century was the end point of the Southern Pacific steam trains and later also their Interurban Electric Railway trains that serviced the East Bay. The Key System trains terminated at their own pier to the north of the Oakland Mole until the completion of the Bay Bridge allowed them to roll all the way to the Transbay Terminal.''' | '''The Oakland Mole in early 20th century was the end point of the Southern Pacific steam trains and later also their Interurban Electric Railway trains that serviced the East Bay. The Key System trains terminated at their own pier to the north of the Oakland Mole until the completion of the Bay Bridge allowed them to roll all the way to the [[Transbay Terminal|Transbay Terminal]].''' | ||

''Photo: Shaping San Francisco'' | ''Photo: Shaping San Francisco'' | ||

[[Image:Keysystemmap. | [[Image:Keysystemmap.jpg|800px]] | ||

'''Key System map, early 20th century''' | '''Key System map, early 20th century''' | ||

As part of its business strategy, the company sold off plots of land for private development that could be served by its streetcars. As the years went by, the SFOSJR evolved into what became known as the Key System, so named because its track configuration and ferry piers resembled an old-fashioned skeleton key. It provided service from Berkeley, through Piedmont and Oakland to San Leandro, and eventually over the lower deck of the Bay Bridge. One example of how the rail service was integrated with the company’s real estate development was the E line. Its streetcars went directly to the Claremont Hotel, terminating between two tennis courts on the lower grounds that are still there today. Though Borax Smith was forced out of the company in 1911 by its investors, the system continued to thrive, particularly during World War II. After the war, the majority of its shares were bought up by a new company with a very different agenda. | |||

<iframe src=" | <font size=4>A Scandal Brews as a Plot Unfolds</font size> | ||

While the effort was being made to move forward on the Joint Army-Navy Board’s recommendation, the Key System was beginning to go through some dramatic changes. As early as 1947, service was being cut back by the system’s new owner, Pacific City Lines, a subsidiary of National City Lines. During the war years, the Key System had seen its highest ridership since first operating, in part because no new automobiles coming off the assembly lines meant options for travel were limited and mass transit was king. After the war ended, however, the stated reason for reducing Key System service was sliding ridership, particularly on local lines. A contributing factor was deferred maintenance and a reduced reliability of service. At the same time, a fare increase may also have had some negative impact on ridership. It’s not clear what the “elasticity of demand” was at the time, but in today’s transit marketing mix, that is an important factor when determining periodic fare increases. The formula pits increased revenue against a calculated ridership decrease on a percentage basis. For example, if fares on a system are increased by, say, 5 percent, and ridership decreases by 1 or 2 percent, revenue more than likely wins hands down. | |||

Meanwhile, although the Key System commute service to San Francisco was still holding its own, it too saw a dramatic decline over the years. Transbay ridership in 1946 was 22 million, dropping to 9.8 million by 1952. It would be another six years before the Key System’s demise. The last train crossed the Bay Bridge in 1958, after which the system’s infrastructure went by way of the wrecking crew. Although a major effort was made by AC Transit to keep the tracks for possible future use, in the end it was not successful. Meanwhile, about thirty of the two-unit cars from the fleet were sold to Buenos Aires, Argentina, for that city’s federal rail system, and a few of the cars were saved and sent to the California Railway Museum (now the Western Railway Museum) in Rio Vista, California. | |||

As it turned out, National City Lines (NCL) was actually a holding company for General Motors, the Firestone Tire Company, Phil lips Petroleum, and Standard Oil of California. NCL was formed in 1936 after taking over a small bus company in Minnesota with the same name. The new company’s express purpose was to acquire privately owned rail lines across the country and replace those lines with buses. In its first year alone, NCL bought thirteen streetcar systems. The following year, Pacific City Lines (PCL) was formed to buy rail transit systems in the West. By 1947, NCL and PCL combined had purchased more than one hundred electric streetcar lines in forty-five cities. In city after city, the rail systems were dismantled and replaced by buses. | |||

In 1947, NCL and its subsidiary, PCL, were indicted by the federal district court in Los Angeles and convicted of conspiring to monopolize the sale of buses in those cities where they had purchased privately owned streetcar systems. The parent company was fined $5,000, and top executives were fined $1 each for their role in the scheme. Meanwhile, in 1948 local Key System trains in the East Bay, as in other cities, were replaced by buses. It was dubbed “the Great American Street- car Scandal.” | |||

Still, the economics of owning and operating a local-service transit company were becoming untenable. More and more systems serving municipal or urban centers across the country were being taken over by public agencies before they closed down under private ownership. In 1958 the newly formed Alameda–Contra Costa Transit District (AC Transit) bought the Key System and began operating local and inter-county bus service, including service over the San Francisco– Oakland Bay Bridge to the East Bay Terminal (later the Transbay Terminal) in San Francisco. | |||

At the same time that the new BART District was taking shape, AC Transit, the newly created interurban bus service (which had purchased the Key System) had an issue. Against the desire of the State Division of Highways and Toll Bridge Authority, AC Transit wanted to continue to operate train service across the Bay Bridge to the East Bay Terminal (later the Transbay Terminal) in San Francisco. The agency hired De Leuw, Cather & Company to study whether or not the tracks across the lower deck of the Bay Bridge should be maintained in the face of impending demolition. De Leuw, Cather came back with a recommendation that the tracks be kept and that some form of rail service continue. However, the BARTD board, which now had jurisdiction over transbay rail service, moved to ensure that the tracks would be dismantled and thus blocked any attempt to keep them. This aligned well with the state’s plans to turn the lower deck into a section of the [[The Freeway Revolt|freeway system]]. | |||

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/0027_March_of_Progress_The_03_35_22_00" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | |||

'''The March of Progress: Tour of the modern interurban trolley system of San Francisco's East Bay and over the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. Predicts the bright postwar future of streetcar transit, with visionary images of advanced-design railcars. The Key System transbay service was abandoned early Sunday morning, April 20, 1958.''' | '''The March of Progress: Tour of the modern interurban trolley system of San Francisco's East Bay and over the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. Predicts the bright postwar future of streetcar transit, with visionary images of advanced-design railcars. The Key System transbay service was abandoned early Sunday morning, April 20, 1958.''' | ||

| Line 61: | Line 100: | ||

''Source: Facebook download'' | ''Source: Facebook download'' | ||

<hr> | |||

[[Image:BART-cover-RGB-onlineuse.jpg|260px|left]] | |||

''Originally published in [https://heydaybooks.com/catalog/bart-the-dramatic-history-of-the-bay-area-rapid-transit-system/ ''BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System'' Heyday Books]: Berkeley CA, 2016'' | |||

<hr> | <hr> | ||

| Line 68: | Line 113: | ||

[[Transbay Terminal|Prev. Document]] [[A VISIT TO THE BAY AREA IN 1835|Next Document]] | [[Transbay Terminal|Prev. Document]] [[A VISIT TO THE BAY AREA IN 1835|Next Document]] | ||

[[category:transit]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:East Bay]] [[category:1950s]] | [[category:transit]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:1940s]] [[category:East Bay]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:BART]] [[category:Book Excerpts]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:25, 16 September 2024

Historical Essay

by Michael C. Healy

Text originally published in BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System Heyday Books: Berkeley CA, 2016

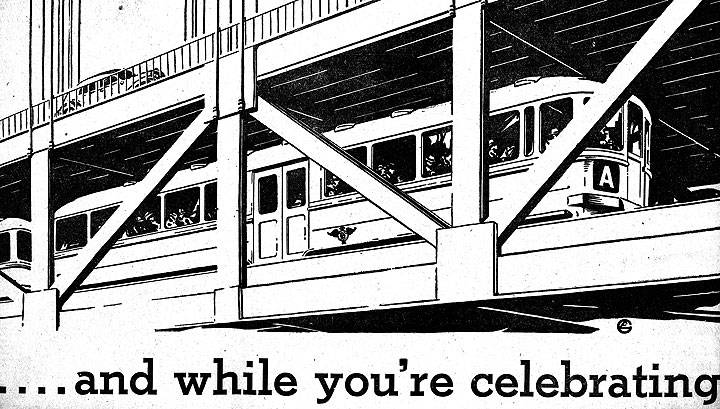

A Key System train on the Bay Bridge, depicted in the opening celebratory newspaper.

The Key System's B train enters the Bay Bridge, c. 1940s.

Photo: Emiliano Echeverria, via Facebook

Key System A train on the Bay Bridge, 1940s.

Photographer unknown

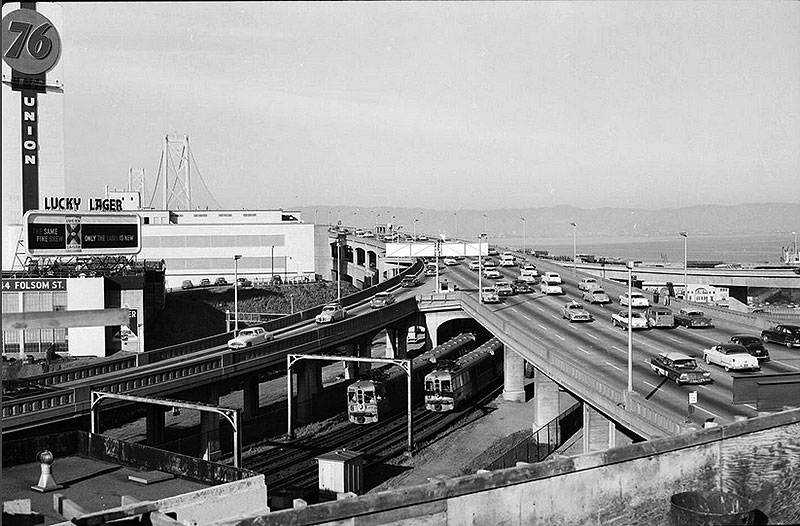

Key Trains exiting Bay Bridge, c. 1956.

Photo: SFMemory.org

The Key System first began operating on October 26, 1903, as the San Francisco, Oakland, and San Jose Railway (SFOSJR), founded by Francis Marion “Borax” Smith and a partner, Frank C. Havens. Its primary competitor at the time was the Inter Urban Rail Transit Company (IURT), which began service in the late 1800s and was still a steam operation. IURT was owned by Southern Pacific. Eventually, IURT converted to electricity and became the East Bay Interurban Electric Railway (IER). While it served many of the same areas that SFOSJR had, it eventually ceased operations and sold much of its equipment to SFOSJR long after that operation had been redubbed the Key System.

As part of its transit mix, the SFOSJR owned a fleet of ferries to provide transbay service for commuters to San Francisco. Among them was Borax Smith, who had built a fortune from his namesake cleaning product, Borax. (His company’s logo, the 20 Mule Team wagon, was by then nationally famous.) After settling in Oakland in the late 1800s, he began to think of new enterprises, and he saw an opportunity in the transportation business, although his venture into mass transit had more to do with real estate development than simply wanting to help people move from place to place. Smith and his partner believed that rail transit could support development along its rights-of- way, a natural symbiotic relationship: create the destination and then transport people to it. Perhaps the experience of the transcontinental railroad, where whole towns sprang up along its owned right-of-way, spurred the idea. In other words, the transcontinental railroad was in the real estate business as much as it was in the transportation business.

The parent company of the new electric streetcar system, which had several investors, was in fact called Realty Syndicate. The company acquired large tracts of land in the East Bay and built two hotels, one of which was the famous Claremont, a towering classic white monument from a bygone era that still thrives today as a luxurious resort.

The Claremont Hotel, built originally by the Realty Syndicate as an anchor for the E-Claremont streetcar line.

Photo: courtesy City of Oakland

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/6358_HM_Key_System_ca_1959_01_15_49_00" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Home movies of VS trains on Key System viaduct around Transbay Terminal area; F train along right-of-way in East Bay; Scenes of Bay Area Electric Railroad Association Special (older yellow car) on East Bay streets; North Berkeley tunnel (Shattuck-Solano); downtown Berkeley

Video: Prelinger Archive

Before the Bay Bridge the Key System trains ended on the "mole" at the end of the landfill spit where they discharged their passengers who then boarded ferries to cross the Bay to San Francisco. This is actually the second "temporary" terminal used until the trains ran on the bridge. The original terminal was destroyed in a fire on the night of May 6, 1933 which destroyed the building, 14 interurban cars and the ferry Peralta.

The Oakland Mole ferry slip in the early 1900s.

Photo: Bancroft Library, 1905.17146-17161

The Oakland Mole in early 20th century was the end point of the Southern Pacific steam trains and later also their Interurban Electric Railway trains that serviced the East Bay. The Key System trains terminated at their own pier to the north of the Oakland Mole until the completion of the Bay Bridge allowed them to roll all the way to the Transbay Terminal.

Photo: Shaping San Francisco

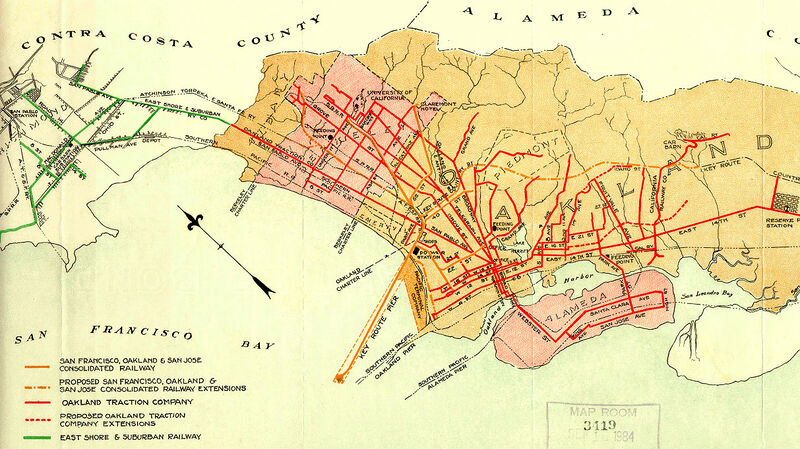

Key System map, early 20th century

As part of its business strategy, the company sold off plots of land for private development that could be served by its streetcars. As the years went by, the SFOSJR evolved into what became known as the Key System, so named because its track configuration and ferry piers resembled an old-fashioned skeleton key. It provided service from Berkeley, through Piedmont and Oakland to San Leandro, and eventually over the lower deck of the Bay Bridge. One example of how the rail service was integrated with the company’s real estate development was the E line. Its streetcars went directly to the Claremont Hotel, terminating between two tennis courts on the lower grounds that are still there today. Though Borax Smith was forced out of the company in 1911 by its investors, the system continued to thrive, particularly during World War II. After the war, the majority of its shares were bought up by a new company with a very different agenda.

A Scandal Brews as a Plot Unfolds

While the effort was being made to move forward on the Joint Army-Navy Board’s recommendation, the Key System was beginning to go through some dramatic changes. As early as 1947, service was being cut back by the system’s new owner, Pacific City Lines, a subsidiary of National City Lines. During the war years, the Key System had seen its highest ridership since first operating, in part because no new automobiles coming off the assembly lines meant options for travel were limited and mass transit was king. After the war ended, however, the stated reason for reducing Key System service was sliding ridership, particularly on local lines. A contributing factor was deferred maintenance and a reduced reliability of service. At the same time, a fare increase may also have had some negative impact on ridership. It’s not clear what the “elasticity of demand” was at the time, but in today’s transit marketing mix, that is an important factor when determining periodic fare increases. The formula pits increased revenue against a calculated ridership decrease on a percentage basis. For example, if fares on a system are increased by, say, 5 percent, and ridership decreases by 1 or 2 percent, revenue more than likely wins hands down.

Meanwhile, although the Key System commute service to San Francisco was still holding its own, it too saw a dramatic decline over the years. Transbay ridership in 1946 was 22 million, dropping to 9.8 million by 1952. It would be another six years before the Key System’s demise. The last train crossed the Bay Bridge in 1958, after which the system’s infrastructure went by way of the wrecking crew. Although a major effort was made by AC Transit to keep the tracks for possible future use, in the end it was not successful. Meanwhile, about thirty of the two-unit cars from the fleet were sold to Buenos Aires, Argentina, for that city’s federal rail system, and a few of the cars were saved and sent to the California Railway Museum (now the Western Railway Museum) in Rio Vista, California.

As it turned out, National City Lines (NCL) was actually a holding company for General Motors, the Firestone Tire Company, Phil lips Petroleum, and Standard Oil of California. NCL was formed in 1936 after taking over a small bus company in Minnesota with the same name. The new company’s express purpose was to acquire privately owned rail lines across the country and replace those lines with buses. In its first year alone, NCL bought thirteen streetcar systems. The following year, Pacific City Lines (PCL) was formed to buy rail transit systems in the West. By 1947, NCL and PCL combined had purchased more than one hundred electric streetcar lines in forty-five cities. In city after city, the rail systems were dismantled and replaced by buses.

In 1947, NCL and its subsidiary, PCL, were indicted by the federal district court in Los Angeles and convicted of conspiring to monopolize the sale of buses in those cities where they had purchased privately owned streetcar systems. The parent company was fined $5,000, and top executives were fined $1 each for their role in the scheme. Meanwhile, in 1948 local Key System trains in the East Bay, as in other cities, were replaced by buses. It was dubbed “the Great American Street- car Scandal.”

Still, the economics of owning and operating a local-service transit company were becoming untenable. More and more systems serving municipal or urban centers across the country were being taken over by public agencies before they closed down under private ownership. In 1958 the newly formed Alameda–Contra Costa Transit District (AC Transit) bought the Key System and began operating local and inter-county bus service, including service over the San Francisco– Oakland Bay Bridge to the East Bay Terminal (later the Transbay Terminal) in San Francisco.

At the same time that the new BART District was taking shape, AC Transit, the newly created interurban bus service (which had purchased the Key System) had an issue. Against the desire of the State Division of Highways and Toll Bridge Authority, AC Transit wanted to continue to operate train service across the Bay Bridge to the East Bay Terminal (later the Transbay Terminal) in San Francisco. The agency hired De Leuw, Cather & Company to study whether or not the tracks across the lower deck of the Bay Bridge should be maintained in the face of impending demolition. De Leuw, Cather came back with a recommendation that the tracks be kept and that some form of rail service continue. However, the BARTD board, which now had jurisdiction over transbay rail service, moved to ensure that the tracks would be dismantled and thus blocked any attempt to keep them. This aligned well with the state’s plans to turn the lower deck into a section of the freeway system.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/0027_March_of_Progress_The_03_35_22_00" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

The March of Progress: Tour of the modern interurban trolley system of San Francisco's East Bay and over the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. Predicts the bright postwar future of streetcar transit, with visionary images of advanced-design railcars. The Key System transbay service was abandoned early Sunday morning, April 20, 1958.

Video: Prelinger Archive

An advertisement from the Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Company welcoming the new, modern Bay Bridge.

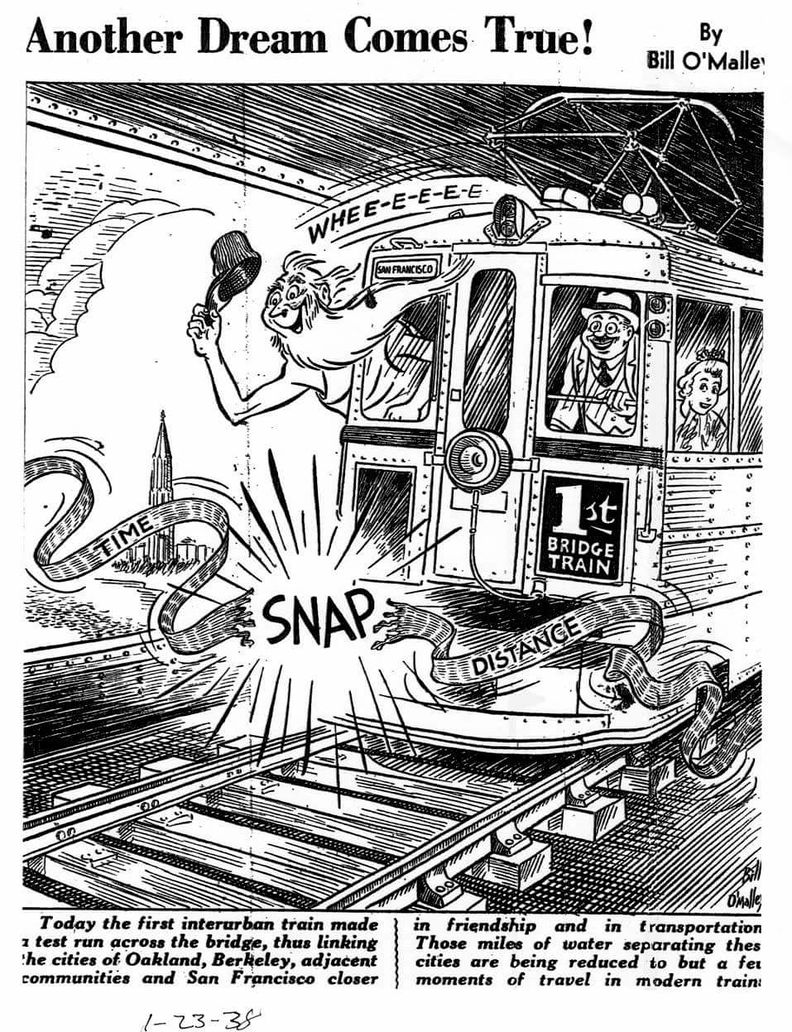

Celebrating the 1938 trial run of the Key System train across the Bay Bridge.

Source: Facebook download

Originally published in BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System Heyday Books: Berkeley CA, 2016