Bay Bridge Artery: Difference between revisions

(added new photo) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | ||

''by Chris Carlsson, 2013'' | |||

[[Image:Baybridge-with-old-skyline-c1958-photo-by-Kurt-Bank.jpg]] | [[Image:Baybridge-with-old-skyline-c1958-photo-by-Kurt-Bank.jpg]] | ||

| Line 6: | Line 8: | ||

''Photo: Kurt Bank'' | ''Photo: Kurt Bank'' | ||

[[Image:220px-Lewis Mumford portrait.jpg|130px|right]] <blockquote>''"The Bay Bridge, between San Francisco and Oakland, brought far greater damage than benefits to both cities: it pumped up a once unnecessary volume of private traffic between them, at a great expense in expressway building and at a great waste in time and tension, spent crawling through rush-hour congestion. This traffic eventually wiped out, by impoverishment, the excellent rapid transit that had been installed on the Bay Bridge (the [[Key System and March of Progress|Key System]]) a form of transportation that the citizens of San Francisco have now repentantly voted to restore (the [[BART: Bechtel's Baby|BART system]]), at an expense far greater than the cost of the original system. The ferry ride across the bay from Oakland was one of the regions greatest recreational resources — an incomparable experience, so exhilarating, at almost any time of the day, that one often sought an excuse for making the journey. It was not a long ride — not more than twenty-five minutes or so, and certainly not longer than the present depressing rush-hour crawl over the bridge."'' | |||

''-- Lewis Mumford, 1963''</blockquote> | |||

[[Image:Exiting-Bay-Bridge-1953ish 3002.jpg]] | [[Image:Exiting-Bay-Bridge-1953ish 3002.jpg]] | ||

| Line 15: | Line 21: | ||

''Photos: San Francisco Planning Commmission archives'' | ''Photos: San Francisco Planning Commmission archives'' | ||

The September 2013 opening of a new east span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge culminates a years-long process to fix the structure after it was damaged during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Much attention has been paid to the disputes among engineers over the relative safety and stability of the self-suspending design of its signature tower, but little attention has been paid to the context of the Bay Bridge, its half-century role as an impediment to cross-Bay mobility for bicyclists and pedestrians. | |||

The civic celebrations that accompanied the new east span were considerably less exuberant than the Bridge’s original opening in 1936. At that time thousands of people walked onto the Bridge despite it being declared off-limits to pedestrians, a status it has retained to this day. The overarching emphasis on the Bay Bridge as the central artery for automobile traffic to enter and leave San Francisco has prevailed for over a half century, but it didn't start out that way. From its [[Bay Bridge Work|1936 opening]], the Bridge was designed to accommodate a rising torrent of car traffic, but it took more than twenty years before the Bridge was dedicated to motorized transport only. From 1936 to 1958 it had six lanes on the top deck, three each going east and west for automobiles, while the lower deck had three lanes for trucks and buses, and two tracks for three different train systems to bring passengers into downtown San Francisco. | |||

[[Image:1926 multiple route bridge plans 8222466721 1c770c7ba8 o.jpg|720px|thumb]] | |||

'''1926 proposals for different bridge routes across the Bay.''' | |||

''Image: courtesy Eric Fischer'' | |||

[[Image:Emperor-norton.jpg|70px|right]] <blockquote><font size=4>'''Proclamation '''</font size><br> | |||

The following is decreed and ordered to be carried into execution as soon as convenient:<br> | |||

1. That a suspension bridge be built from Oakland Point to Goat [now Yerba Buena] Island, and thence to Telegraph Hill; provided such bridge can be built without injury to the navigable waters of the Bay of San Francisco.<br> | |||

2. That the Central Pacific Railroad Company be granted franchises to lay down tracks and run cars from Telegraph Hill and along the city front to Mission Bay.<br> | |||

3. That all deeds of land by the Washington Government since the establishment of our Empire are hereby declared null and void unless our Imperial signature is first obtained thereto.<br> | |||

—Norton I, 1870s</blockquote> | |||

[[Image:ProposedSanFranciscoBayBridge2.jpg|720px]] | |||

'''Early 20th century vision of proposed Bay Bridge.''' | |||

''Image: Wikimedia commons'' | |||

[[Image:Alternate routes for Bay Bridge 1927 4421366172 3eda7a32b3 o.jpg|720px|thumb]] | |||

'''Alternate routes for Bay Bridge as proposed in 1927.''' | |||

''Image: courtesy Eric Fischer'' | |||

Prior to the completion of the Bay Bridge, the extensive [[Ferries on the Bay|ferry system]] carried nearly 50 million commuters per year across the Bay. [[Image:Motorland-cover-1927 3043.jpg|80px|right]] Starting in 1939, the Key System brought East Bay commuters across the bridge, and the Sacramento Northern railroad transported people from the northern Central Valley all the way into the heart of the city. But the train systems were losing money, and bridge access didn’t reverse their fortunes. By the end of the 1950s, the prevailing logic of “Motordom” was at full throttle. The associated industries and government bureaucracies dedicated to the expansion of social dependence on private automobiles have always insisted that the solution for traffic congestion was to add capacity. | |||

[[Image:Under Bay Bridge Jan 3 1937 Ben Valdez 411293 4269558294080 1164079004 o.jpg|720px]] | [[Image:Under Bay Bridge Jan 3 1937 Ben Valdez 411293 4269558294080 1164079004 o.jpg|720px]] | ||

| Line 24: | Line 59: | ||

''Photo: courtesy Ben Valdez'' | ''Photo: courtesy Ben Valdez'' | ||

San Francisco’s streets had already been [[Automobiles Take Over San Francisco Streets|captured by this logic]] during the late 1920s and early 1930s, as city planners widened roads and imposed new rules on street use, including stop lights, lanes, and crosswalks, all of which was a departure from centuries of unregulated road use by pedestrians and slow-moving vehicles. The impetus to build the Bay Bridge emerged during this period when automobile use was rapidly expanding. Built in just three years during the depths of the Depression, 27 workers died while building it, some falling into the concrete as it was being poured for the anchorage and foundations. Work could not stop to extricate them. Over the three years it took to complete, nearly 8000 men worked on the bridge project. | |||

[[Image:Bb007x2.jpg]] | |||

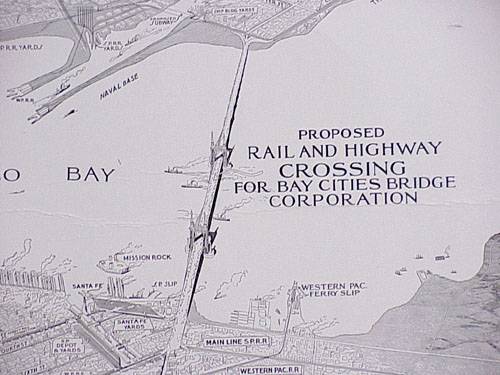

'''Another early bridge plan, this one anticipating plans in the 1960s and '70s for a "southern crossing."''' | |||

''Image: courtesy Eric Fischer'' | |||

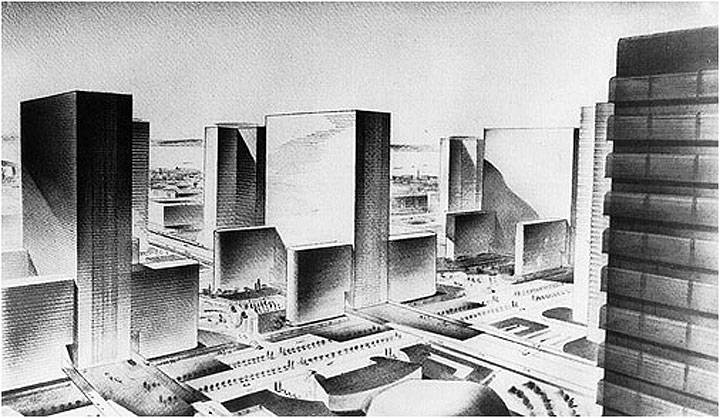

The automobilistic modernism that shaped popular imagination was on full view at the [[Treasure Island Fair: Golden Gate International Exposition|1939 Treasure Island Golden Gate International Exposition]]. There, U.S. Steel created a promotional diorama envisioning San Francisco in the year 1999, depicting the South of Market as a series of massive apartment blocks surrounded by elevated roadways. | |||

[[Image:Us-steel-diorama-16th-st-pier.jpg]] | |||

'''1939 U.S. Steel diorama at Treasure Island World's Fair, note where Bay Bridge touches down in flattened South of Market full of highrise towers.''' | |||

[[Image:Us-steel-diorama-cu.jpg]] | |||

'''U.S. Steel's version of modernist heaven in San Francisco, projected for 1999.''' | |||

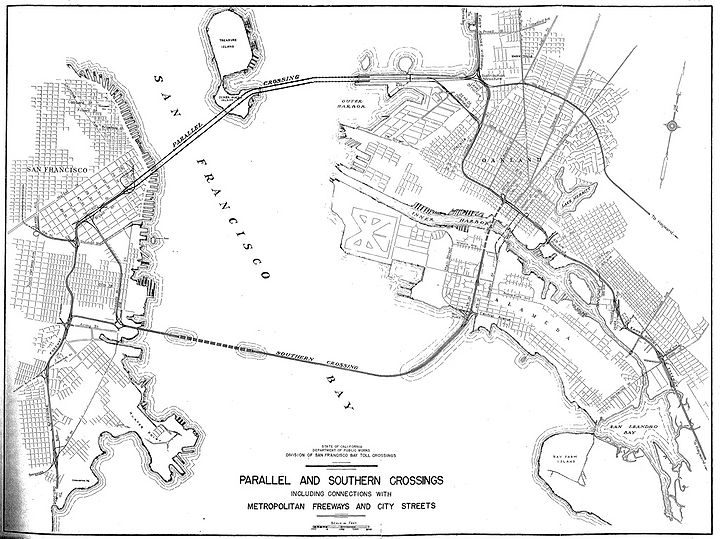

At the end of WWII, plans were proposed to build a second Bay Bridge alongside the first one. Mayor Elmer Robinson went to Washington D.C. to lobby against it, gaining success by convincing the Pentagon that it would be too vulnerable to attack. But plans to build more bay crossings were still coming fast and furious. Already a long causeway bridge called the San Francisco Bay Toll-Bridge was opened in 1929, later modernized and reopened in 1967 as the San Mateo-Hayward Bridge. The Richmond-San Rafael Bridge was opened in 1956. But the California Department of Highways (now known as Caltrans) was determined to build at least a “Southern Crossing,” an idea that didn't completely die until the early 1970s. | |||

[[Image:Parallel bay bridge and southern crossing 1948 4247129432 3af57996d3 b.jpg|720px|thumb]] | |||

'''Plans for parallel Bay Bridge and a southern crossing in this 1948 rendering.''' | |||

''Image: courtesy Eric Fischer'' | |||

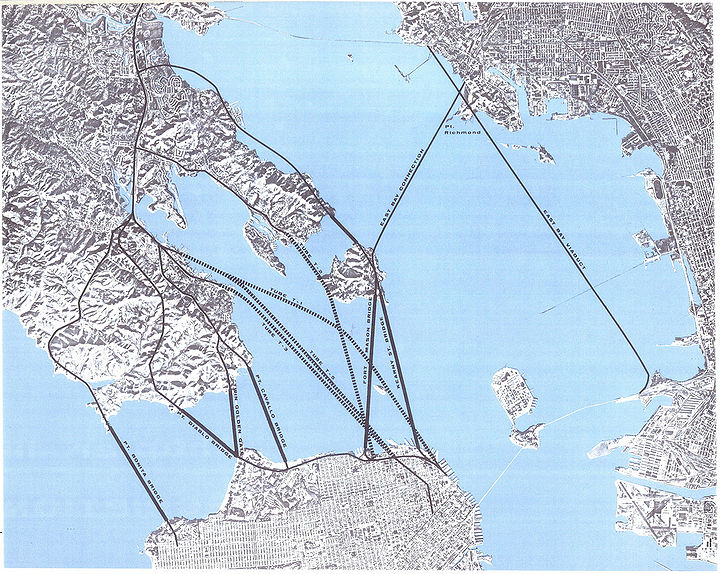

[[Image:North and east routes 4255511395 a659b99779 b.jpg|720px|thumb]] | |||

'''A frenzy of planning led to a crazy proliferation of proposed tunnels and bridges to connect across the Bay, seen here going north and east from San Francisco.''' | |||

''Image: courtesy Eric Fischer'' | |||

During this same post-WWII era, highway planners got a huge boost when the federal government launched the interstate highway program. The Bay Bridge was already the western end of the so-called “Lincoln Highway,” but now it would be the western keystone of Interstate 80. Meanwhile, in San Francisco planners were busy laying out and then building freeways through the city. The Bay Bridge had originally landed on 5th Street between Bryant and Harrison, but by the mid-1950s the James Lick Freeway curved behind SF General Hospital and through the South of Market to meet up with the Bridge. The Embarcadero Freeway was also connected directly to the Bridge by the late 1950s. | |||

[[Image:Lincoln-highway-bw.jpg]] | |||

'''Texaco oil company ad for the Lincoln Highway.''' | |||

''Image: Shaping San Francisco'' | |||

While all this building was going on, a [[The Freeway Revolt|citizen revolt]] rose against the highway builders when they saw that thousands of homes in a dozen neighborhoods were slated for demolition to make way for the elevated concrete slabs of the freeway system. It was during this heated controversy over plans to build highways that the Bay Bridge was reconfigured for high speed automobile traffic, five lanes westbound on the top deck and five lanes eastbound on the lower deck. The assumption of the Department of Highways was that most of the new elevated freeways would be built, connecting the south and west sides of San Francisco with the two bridges (Bay and Golden Gate). Much to the shock of the state planners, and even to the whole country, San Francisco refused to build those freeways. It took nearly ten years, but by 1965 the final blow was struck killing plans to build the Panhandle-Golden Gate Park freeway, and also the Golden Gateway freeway that was slated to ring the city’s waterfront, continuing the path of the Embarcadero around to the Golden Gate Bridge. | |||

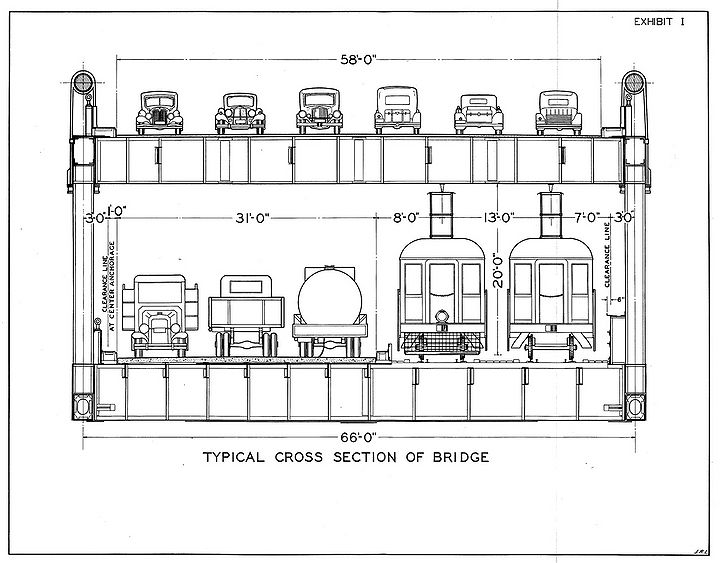

[[Image:1933 cross section of bridge traffic 5448636057 e1f658cc9a b.jpg|720px]] | |||

'''The original configuration of traffic on the Bay Bridge.''' | |||

''Image: courtesy Eric Fischer'' | |||

[[Image:Lower-deck-w-two-way-trucks-and-trains.jpg]] | |||

'''Lower deck in 1940s, trucks, buses, and trains.''' | |||

The Bay Bridge had been reconfigured to maximize auto throughput at 50 mph to connect to the growing network of freeways. Fantasies of smooth flowing high-speed traffic, combined with the incessant advertising of the supposed “freedom of the road,” were nevertheless confronted by the actual conditions: severe traffic jams and daily congestion. The Bridge was usually clogged by rush hour traffic, or severely congested any time of day or night when the inevitable crashes or mechanical breakdowns happened. The “Freeway Revolt” had pushed local planners to embrace BART to replace the commuting capacity they had projected from the expanded freeway systems (and to replace the now destroyed Key surface trolley system), but the same “Revolt” had not led to rethinking how best to use the capacity of the Bay Bridge. | |||

It was not until the 1990s that cycling activists managed to dent the transit professionals’ myopic consensus in favor of automobiles only. Finally Caltrans was pressured into adding a bicycle and pedestrian path to the new east span. But they were not happy about it, and claimed it would cost hundreds of millions more to build. After waiting all this time, the priorities of Caltrans haven’t noticeably changed. They opened the new east span to automobile traffic at the beginning of September, 2013, but the new bike lane is only a bike pier for the next two years. That’s what they claim it will take to finish connecting the bike/ped lane to Yerba Buena Island. Even then, there will be no access to the west span and no way for bicyclists to ride across the Bay Bridge from San Francisco to Oakland or vice versa. | |||

Caltrans claims they are working on a plan to build new decks off the side of the west span, a project expected to take ten years and cost between $500 million and $1 billion! The obvious solution of reorganizing the top deck on the west span, returning it to the original six lanes, reserving one for bicyclists and pedestrians, is somehow unacceptable and is getting no attention from Bridge authorities, transit planners, city politicians or even the bicycle coalitions on both sides of the bay. | |||

[[Image:Eric fischer end of the bike pier 9668892444 b5e8c24526 b.jpg|720px]] | |||

'''Bicyclists reach end of the "Pier" while cars speed by on their way to San Francisco... it's not expected to connect to Yerba Buena Island until 2015.''' | |||

'' | ''Photo: Eric Fischer'' | ||

[[Where Devil's Dictionary Author Sold His Soul for Coin |Prev. Document]] [[Bay Bridge Work |Next Document]] | [[Where Devil's Dictionary Author Sold His Soul for Coin |Prev. Document]] [[Bay Bridge Work |Next Document]] | ||

[[category:SOMA]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:San Francisco outside the city]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:Bridges]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:transit]] | [[category:SOMA]] [[category:1930s]] [[category:San Francisco outside the city]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:Bridges]] [[category:1950s]] [[category:transit]] [[category:2010s]] | ||

Revision as of 22:33, 13 September 2013

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson, 2013

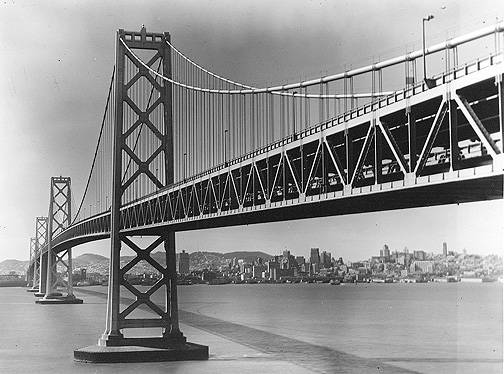

1958 photo of Bay Bridge and San Francisco skyline from Yerba Buena Island.

Photo: Kurt Bank

"The Bay Bridge, between San Francisco and Oakland, brought far greater damage than benefits to both cities: it pumped up a once unnecessary volume of private traffic between them, at a great expense in expressway building and at a great waste in time and tension, spent crawling through rush-hour congestion. This traffic eventually wiped out, by impoverishment, the excellent rapid transit that had been installed on the Bay Bridge (the Key System) a form of transportation that the citizens of San Francisco have now repentantly voted to restore (the BART system), at an expense far greater than the cost of the original system. The ferry ride across the bay from Oakland was one of the regions greatest recreational resources — an incomparable experience, so exhilarating, at almost any time of the day, that one often sought an excuse for making the journey. It was not a long ride — not more than twenty-five minutes or so, and certainly not longer than the present depressing rush-hour crawl over the bridge." -- Lewis Mumford, 1963

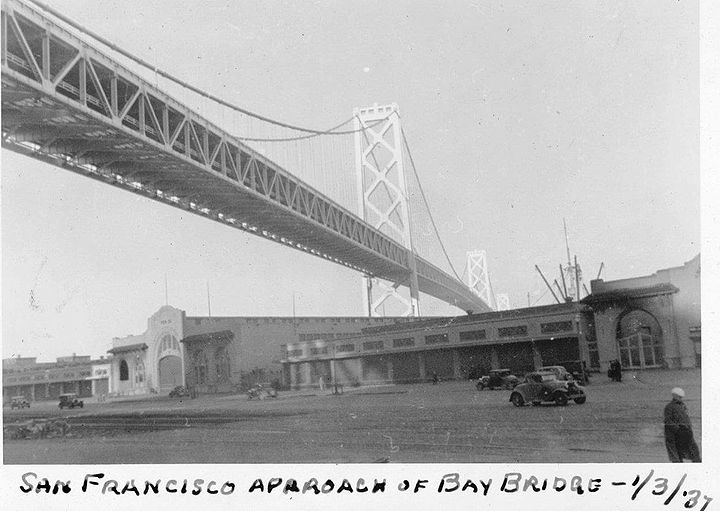

Before the Bay Bridge was linked to the freeway system after 1953 cars got on and off on long cement ramps that hit the city streets on 5th between Harrison and Bryant. In those days car traffic was limited to the top deck, where there were three lanes in each direction.

Photos: San Francisco Planning Commmission archives

The September 2013 opening of a new east span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge culminates a years-long process to fix the structure after it was damaged during the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Much attention has been paid to the disputes among engineers over the relative safety and stability of the self-suspending design of its signature tower, but little attention has been paid to the context of the Bay Bridge, its half-century role as an impediment to cross-Bay mobility for bicyclists and pedestrians.

The civic celebrations that accompanied the new east span were considerably less exuberant than the Bridge’s original opening in 1936. At that time thousands of people walked onto the Bridge despite it being declared off-limits to pedestrians, a status it has retained to this day. The overarching emphasis on the Bay Bridge as the central artery for automobile traffic to enter and leave San Francisco has prevailed for over a half century, but it didn't start out that way. From its 1936 opening, the Bridge was designed to accommodate a rising torrent of car traffic, but it took more than twenty years before the Bridge was dedicated to motorized transport only. From 1936 to 1958 it had six lanes on the top deck, three each going east and west for automobiles, while the lower deck had three lanes for trucks and buses, and two tracks for three different train systems to bring passengers into downtown San Francisco.

1926 proposals for different bridge routes across the Bay.

Image: courtesy Eric Fischer

Proclamation

The following is decreed and ordered to be carried into execution as soon as convenient:

1. That a suspension bridge be built from Oakland Point to Goat [now Yerba Buena] Island, and thence to Telegraph Hill; provided such bridge can be built without injury to the navigable waters of the Bay of San Francisco.

2. That the Central Pacific Railroad Company be granted franchises to lay down tracks and run cars from Telegraph Hill and along the city front to Mission Bay.

3. That all deeds of land by the Washington Government since the establishment of our Empire are hereby declared null and void unless our Imperial signature is first obtained thereto.

—Norton I, 1870s

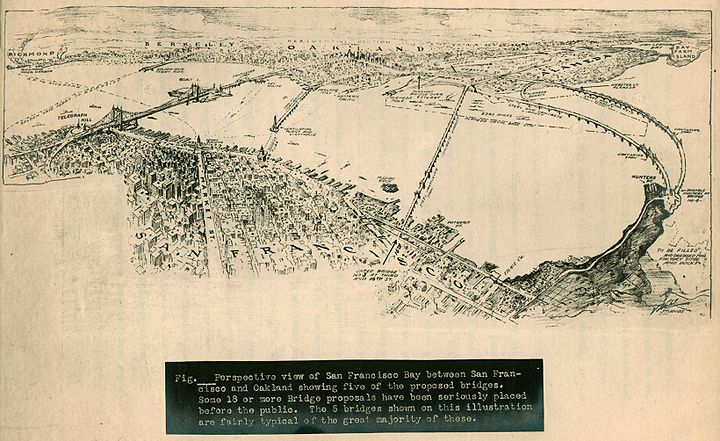

Early 20th century vision of proposed Bay Bridge.

Image: Wikimedia commons

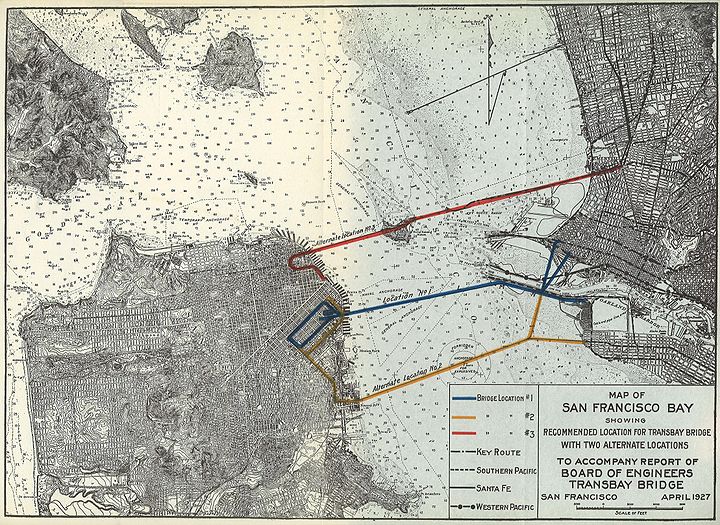

Alternate routes for Bay Bridge as proposed in 1927.

Image: courtesy Eric Fischer

Prior to the completion of the Bay Bridge, the extensive ferry system carried nearly 50 million commuters per year across the Bay.

Starting in 1939, the Key System brought East Bay commuters across the bridge, and the Sacramento Northern railroad transported people from the northern Central Valley all the way into the heart of the city. But the train systems were losing money, and bridge access didn’t reverse their fortunes. By the end of the 1950s, the prevailing logic of “Motordom” was at full throttle. The associated industries and government bureaucracies dedicated to the expansion of social dependence on private automobiles have always insisted that the solution for traffic congestion was to add capacity.

Under the Bay Bridge, January 3, 1937.

Photo: courtesy Ben Valdez

San Francisco’s streets had already been captured by this logic during the late 1920s and early 1930s, as city planners widened roads and imposed new rules on street use, including stop lights, lanes, and crosswalks, all of which was a departure from centuries of unregulated road use by pedestrians and slow-moving vehicles. The impetus to build the Bay Bridge emerged during this period when automobile use was rapidly expanding. Built in just three years during the depths of the Depression, 27 workers died while building it, some falling into the concrete as it was being poured for the anchorage and foundations. Work could not stop to extricate them. Over the three years it took to complete, nearly 8000 men worked on the bridge project.

Another early bridge plan, this one anticipating plans in the 1960s and '70s for a "southern crossing."

Image: courtesy Eric Fischer

The automobilistic modernism that shaped popular imagination was on full view at the 1939 Treasure Island Golden Gate International Exposition. There, U.S. Steel created a promotional diorama envisioning San Francisco in the year 1999, depicting the South of Market as a series of massive apartment blocks surrounded by elevated roadways.

1939 U.S. Steel diorama at Treasure Island World's Fair, note where Bay Bridge touches down in flattened South of Market full of highrise towers.

U.S. Steel's version of modernist heaven in San Francisco, projected for 1999.

At the end of WWII, plans were proposed to build a second Bay Bridge alongside the first one. Mayor Elmer Robinson went to Washington D.C. to lobby against it, gaining success by convincing the Pentagon that it would be too vulnerable to attack. But plans to build more bay crossings were still coming fast and furious. Already a long causeway bridge called the San Francisco Bay Toll-Bridge was opened in 1929, later modernized and reopened in 1967 as the San Mateo-Hayward Bridge. The Richmond-San Rafael Bridge was opened in 1956. But the California Department of Highways (now known as Caltrans) was determined to build at least a “Southern Crossing,” an idea that didn't completely die until the early 1970s.

Plans for parallel Bay Bridge and a southern crossing in this 1948 rendering.

Image: courtesy Eric Fischer

A frenzy of planning led to a crazy proliferation of proposed tunnels and bridges to connect across the Bay, seen here going north and east from San Francisco.

Image: courtesy Eric Fischer

During this same post-WWII era, highway planners got a huge boost when the federal government launched the interstate highway program. The Bay Bridge was already the western end of the so-called “Lincoln Highway,” but now it would be the western keystone of Interstate 80. Meanwhile, in San Francisco planners were busy laying out and then building freeways through the city. The Bay Bridge had originally landed on 5th Street between Bryant and Harrison, but by the mid-1950s the James Lick Freeway curved behind SF General Hospital and through the South of Market to meet up with the Bridge. The Embarcadero Freeway was also connected directly to the Bridge by the late 1950s.

Texaco oil company ad for the Lincoln Highway.

Image: Shaping San Francisco

While all this building was going on, a citizen revolt rose against the highway builders when they saw that thousands of homes in a dozen neighborhoods were slated for demolition to make way for the elevated concrete slabs of the freeway system. It was during this heated controversy over plans to build highways that the Bay Bridge was reconfigured for high speed automobile traffic, five lanes westbound on the top deck and five lanes eastbound on the lower deck. The assumption of the Department of Highways was that most of the new elevated freeways would be built, connecting the south and west sides of San Francisco with the two bridges (Bay and Golden Gate). Much to the shock of the state planners, and even to the whole country, San Francisco refused to build those freeways. It took nearly ten years, but by 1965 the final blow was struck killing plans to build the Panhandle-Golden Gate Park freeway, and also the Golden Gateway freeway that was slated to ring the city’s waterfront, continuing the path of the Embarcadero around to the Golden Gate Bridge.

The original configuration of traffic on the Bay Bridge.

Image: courtesy Eric Fischer

Lower deck in 1940s, trucks, buses, and trains.

The Bay Bridge had been reconfigured to maximize auto throughput at 50 mph to connect to the growing network of freeways. Fantasies of smooth flowing high-speed traffic, combined with the incessant advertising of the supposed “freedom of the road,” were nevertheless confronted by the actual conditions: severe traffic jams and daily congestion. The Bridge was usually clogged by rush hour traffic, or severely congested any time of day or night when the inevitable crashes or mechanical breakdowns happened. The “Freeway Revolt” had pushed local planners to embrace BART to replace the commuting capacity they had projected from the expanded freeway systems (and to replace the now destroyed Key surface trolley system), but the same “Revolt” had not led to rethinking how best to use the capacity of the Bay Bridge.

It was not until the 1990s that cycling activists managed to dent the transit professionals’ myopic consensus in favor of automobiles only. Finally Caltrans was pressured into adding a bicycle and pedestrian path to the new east span. But they were not happy about it, and claimed it would cost hundreds of millions more to build. After waiting all this time, the priorities of Caltrans haven’t noticeably changed. They opened the new east span to automobile traffic at the beginning of September, 2013, but the new bike lane is only a bike pier for the next two years. That’s what they claim it will take to finish connecting the bike/ped lane to Yerba Buena Island. Even then, there will be no access to the west span and no way for bicyclists to ride across the Bay Bridge from San Francisco to Oakland or vice versa.

Caltrans claims they are working on a plan to build new decks off the side of the west span, a project expected to take ten years and cost between $500 million and $1 billion! The obvious solution of reorganizing the top deck on the west span, returning it to the original six lanes, reserving one for bicyclists and pedestrians, is somehow unacceptable and is getting no attention from Bridge authorities, transit planners, city politicians or even the bicycle coalitions on both sides of the bay.

File:Eric fischer end of the bike pier 9668892444 b5e8c24526 b.jpg

Bicyclists reach end of the "Pier" while cars speed by on their way to San Francisco... it's not expected to connect to Yerba Buena Island until 2015.

Photo: Eric Fischer