The Heyday of Horsecars: Difference between revisions

(added photo) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | {| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | ||

| colspan="2" | ''' | | colspan="2" | '''Public demand called for an end to walking through the dirt and mud of San Francisco’s early streets, thus, in the late 1840s the horsecar made its way out west after growing in popularity on the east coast. As one of the first forms of urban public transit the horsecars were quickly popular and could be seen all over the city by the 1860s. Along with changing the commute of many San Franciscans in the 1800s, it was a catalyst for many other social and economic changes of the time.''' | ||

Public demand called for an end to walking through the dirt and mud of San Francisco’s early streets, thus, in the late 1840s the horsecar made its way out west after growing in popularity on the east coast. As one of the first forms of urban public transit the horsecars were quickly popular and could be seen all over the city by the 1860s. Along with changing the commute of many San Franciscans in the 1800s, it was a catalyst for many other social and economic changes of the time.''' | |||

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 14:52, 27 March 2019

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

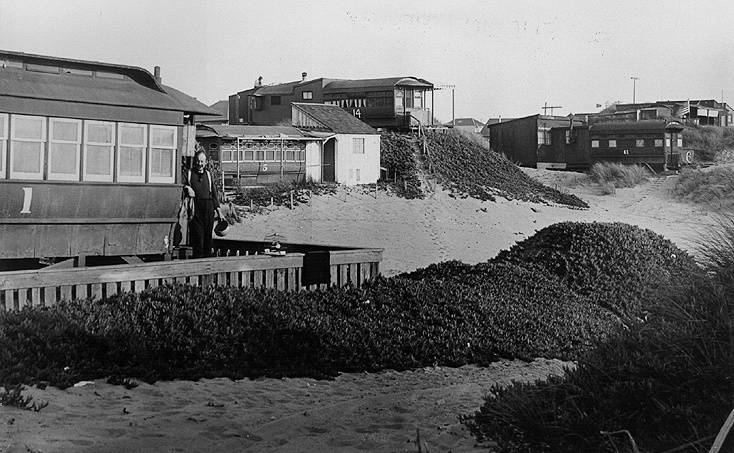

In 1907 the horse was still a major part of the transportation picture, but the horsecars that dominated the 19th century were being replaced.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

| Public demand called for an end to walking through the dirt and mud of San Francisco’s early streets, thus, in the late 1840s the horsecar made its way out west after growing in popularity on the east coast. As one of the first forms of urban public transit the horsecars were quickly popular and could be seen all over the city by the 1860s. Along with changing the commute of many San Franciscans in the 1800s, it was a catalyst for many other social and economic changes of the time. |

After walking through the mud and sand of early San Francisco, locals were ready for other kinds of transportation. A brisk business began as soon as roads could be laid out, relying on horse-drawn omnibuses and hacks (stagecoaches and carriages). The breakthrough came quickly, when the horsecar made it to San Francisco after sweeping the market in eastern cities in the late 1840s.

Unlike the omnibus ride, the horsecar was smoother and went a reliable 6 mph on its steel rails, making regular stops and providing straps for standing passengers to hang on to. As the horsecar regularized urban inner city transit, it helped usher in zoned fare systems and ringing bells for passengers to signal a stop. Not that it was accepted without resistance. Interesting to note, during these days of challenging the dominance of the private automobile over urban space, how at a much earlier juncture in transportation evolution citizens fought the new-fangled horsecars too.

Horsecars line up at Ferry building in San Francisco, 1875.

Photo: Bancroft Library

In the 1956 book Trolley Car Treasury, Frank Rowsome, Jr. describes the attitude that confronted the horsecar advocates:

“Iron-track cars were radically new and very probably dangerous to the established order. The metal strips in the streets would likely cause carriages to turn over. It was felt that property value along such streets would be injured, trade in stores would fall off, and car-riding would cause the lower social orders to become still more contentious.”

The horsecars gained acceptance pretty quickly though. It helped that local merchants usually had a big increase in trade after the start of a new horsecar line on the street in front of their establishments. Not that it was an altogether pleasing experience. The smell tended to stick in your mind. Rowsome describes a “special horsecar smell, blending the odors of smoky coal-oil lamps, sweating horses, and the pungency that came when the straw on the floor was dampened with many a dollop of tobacco juice.”

In San Francisco horsecar lines were crisscrossing the city by the 1860s. Here’s one of the first lines at Market and Post on its way to Woodward’s Gardens:

Horsecar #14 pauses at Post and Market on its way to Woodward's Gardens, c. 1860s.

Photo: Bancroft Library

Horsecar passes 5th and Mission in front of the Old U.S. Mint, 1875.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.jpg

In the 1880 Census there were 233,959 San Franciscans and an estimated 23,000 horses. Just a few years later the horsecar peaked in 1886 when there were 525 horse railways in 300 cities in the U.S. One hundred thousand horses provided the “horse power” to make those carriages go. By then, a generation had adapted to their use and urban development patterns had already begun to change. Instead of having to find housing in dark and dingy tenements next to a factory, a workman could commute 5 or more miles a day on a horsecar, which allowed a growing dispersion and separation of residential from commercial land uses.

But horses need fuel too. A typical streetcar horse ate 30 pounds of grain and hay a day, meaning in 1880 there was demand for about 350 tons a DAY of hay and feed. A booming business brought hay to San Francisco along Channel Street, not far from today's Willie Mays Field. Back in the 19th century Mission Creek was a bustling industrial port handling tons of hay, lumber, and other goods every week.

In the mid-1880s San Francisco needed 350 tons a day of hay and grain to feed its 23,000+ horses. Pictured here, the Annie L, a scow schooner typical of the era.

Photo: San Francisco National Maritime Museum, A12.5,017pl

We can only imagine how bad it smelled. The Brannan Street Wharf was one of the outflow points for San Francisco’s raw sewage, much of which would wash back up Mission Creek and settle on the mudflats at low tide. Shit was a big problem in those days (it still is, we just don’t notice as much!).

How to manage all the horseshit falling on city streets and in the horsecar company stables? San Francisco was lucky since from the mid-1870s on as much horseshit as possible was deposited on the sand dunes that became Golden Gate Park. In eastern cities they had more of a problem with storing it until it could be carted off. A few companies tried to persuade neighbors that an enormous shit pile was not a hazard to public health but a benefit of fine germicidal properties. Snake oil came in a wide variety of forms in those days!

Capitalist rationalization was applied to horse grooming in those early industrial days.

Image: Bancroft Library

According to Rowsome,

The most crucial decision was when to sell off horses in services. (The tannery or glue factory was only a last resort, and meant that someone had miscalculated; most ex-streetcar horses returned to farm life for their last few years.) Horsecar horses led highly regulated lives. They were stabled for nineteen or twenty hours a day, in stalls specified by industry standards as not less than 4 feet wide and 9 feet long. Their workdays were measured in miles, not hours (they were expected to make it 12-15 miles a day).

Like transit systems right up to the present day, social struggles erupted on the horsecars too. In an curious near-coincidence of dates, April 17, 1863 (43 years and a day before the great Quake and Fire of April 18, 1906) is the date Charlotte L. Brown was ordered off an Omnibus Railroad car by the conductor because she wasn’t white.

The story is well-told in a new book Wherever There’s a Fight:

Brown sued the company for two hundred dollars. In response to the lawsuit, Omnibus Railroad justified its conductor's action by arguing that racial segregation was necessary to protect white women and children who might be fearful of riding side by side with an African American, an argument that was commonly used to justify segregation. But in November 1863, a San Francisco superior court judge rejected this reasoning and awarded Brown damages of five cents (the streetcar fare) plus legal costs.

Her success in court, though, did not immediately translate into change. Within days of the judgment, another streetcar conductor forced Brown and her father from a car. The tenacious Brown brought another lawsuit. And in October 1864, District Court Judge C. C. Pratt ruled that San Francisco streetcar segregation was illegal. He stated:

It has been already quite too long tolerated by the dominant race to see with indifference the negro or mulatto treated as a brute, insulted, wronged, enslaved, made to wear a yoke, to tremble before white men, to serve him as a tool, to hold property and life at his will, to surrender to him his intellect and conscience, and to seal his lips and belie his thought through dread of the white man's power.

Unfortunately the local transit systems, often privately owned and quite local to a block or a few, continued to refuse service to African Americans. Three years later, in 1866, Mary Ellen Pleasant filed another suit, this time against the North Beach Municipal Railroad. She, like Brown, was an independent African American woman, and determined to gain her rights; they were also both well known activists in the Abolition movement, Pleasant having been instrumental in establishing the west coast terminus of the Underground Railroad in the 1850s. She won her case and was awarded $500, though the award was overturned by a State Supreme Court appeal even while they affirmed the illegality of enforcing segregation on transit systems. It wasn’t until 1893 that the state of California passed a statewide prohibition on transit segregation.

The last horse-drawn streetcar in San Francisco rolled up Market Street in 1913, but mostly horsecars had been abandoned by the turn of the century. In San Francisco an aggressive capitalist consolidator and modernizer named Patrick Calhoun purchased every independent streetcar line in 1901 and merged them into his United Railroads. An early project was to make uniform the rolling stock and track gauges, which led to the abandonment of the last four miles of horsecars that had been the backbone of transportation just a generation earlier. The cars were already being sold in the mid-1890s to anyone who wanted one, $20 with seats, and $10 without. Famously a number of them ended up in the sand dunes near the beach just south of Golden Gate Park in an odd village that came to be known as Carville by the Sea.

A resident of Carville.

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco