Red Record: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

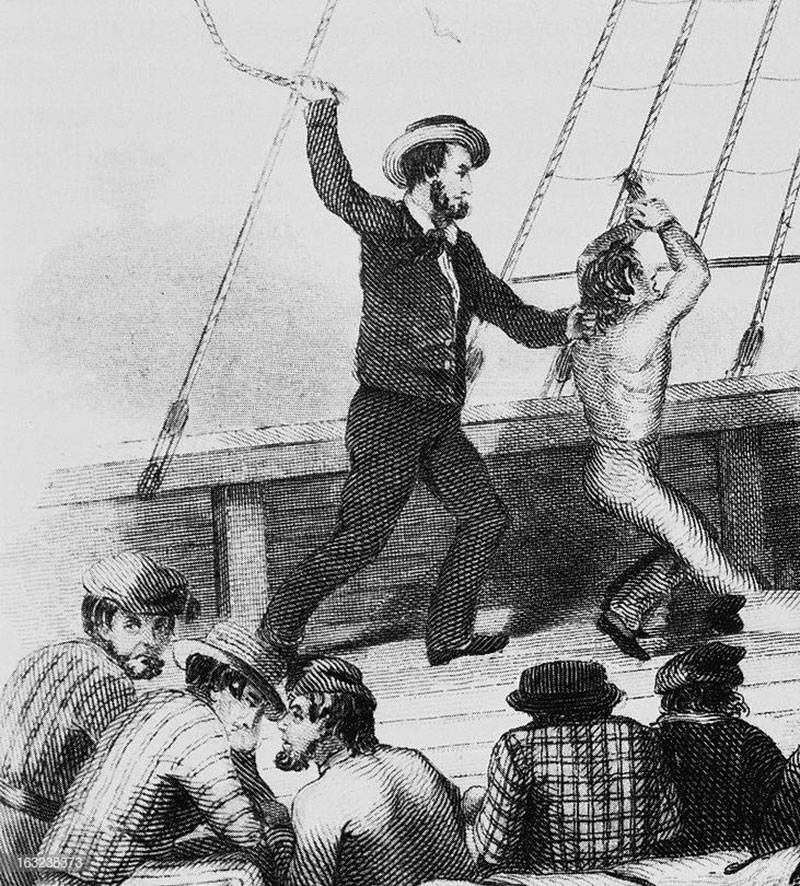

'''Routine beating of sailors at sea during 19th century, when sailors were deemed unworthy of protection from [[Shanghaiing|involuntary servitude]].''' | '''Routine beating of sailors at sea during 19th century, when sailors were deemed unworthy of protection from [[Shanghaiing|involuntary servitude]].''' | ||

< | <font size=4>"Tomorrow Is Also A Day"</font size> | ||

This is sufficient. It was good newspaper copy; the story spread throughout the nation and helped Andrew Furuseth get the Maguire and White Acts passed in Congress. The sailor was on his way to being a "free man." | This is sufficient. It was good newspaper copy; the story spread throughout the nation and helped Andrew Furuseth get the Maguire and White Acts passed in Congress. The sailor was on his way to being a "free man." | ||

Latest revision as of 15:57, 12 July 2020

Historical Essay

by Felix Reisenberg, Jr.

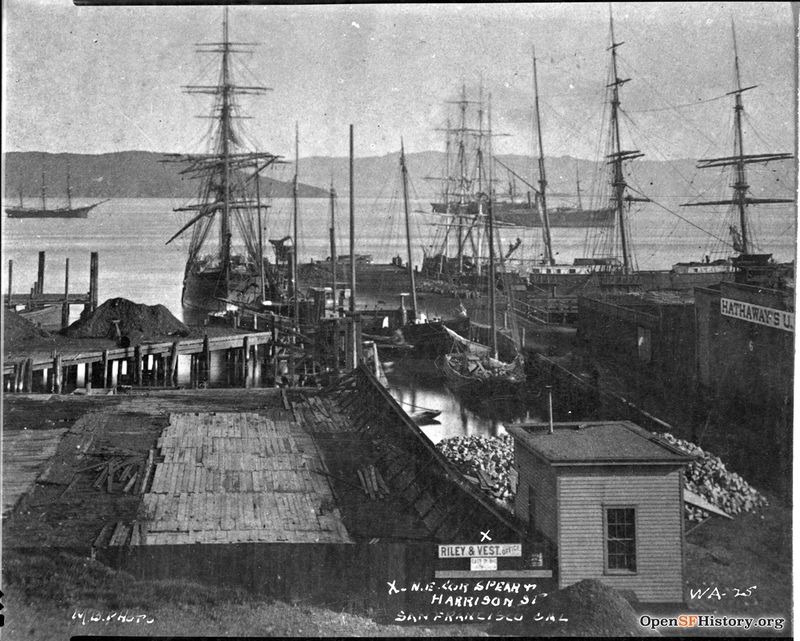

Spear and Harrison, c. 1860s, a couple of decades before the Coast Seamen's Union was founded on a lumber pile near here.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp71.2174

When Sigismund Danielwicz, a member of the International Workmen's Association, not a seafaring man but a labor organizer, elbowed his way into a crowd of seamen on East Street and listened to their excited talk about pay reductions, the first successful sailors' union on San Francisco's waterfront had its beginning. The men were gathered around a poster announcing that off-shore sailors would thereafter receive only twenty-five dollars a month, inland sailors five dollars less. Bad times had come again to shipping on March 5, 1885.

The next night four hundred skeptical seamen, most of them from coasting schooners, answered Danielwicz's invitation to meet on the lumber piles at Folsom Street Wharf and listen to speeches. Few who stood in the dark that night thought anything would come of the organization which was formed. Of the two hundred who joined the Coast Seaman's Union, there were many of the opinion that it would end in failure as had all other sailors' unions at San Francisco since the sixties. Clothing dealers and crimps would worm in and sell the souls of the seamen; new strikes would be called to increase blood money rather than wages; the "Friendly" and "Protective" societies would give away Bibles; but there would be more people doing things to than for poor Jack.

The professional organizers, however, gave the union a strong start; the shore-side officials could be depended upon at least to work for better wages and working conditions. Their success was due largely to the changing of commerce that caused coastwise shipping to replace deep-water trade as San Francisco's mainstay. Though the greatest instances of injustice were perpetuated on the decks of long-voyage ships, the organizers concentrated on the droughers until two thirds of the seamen in those ships had joined the union.

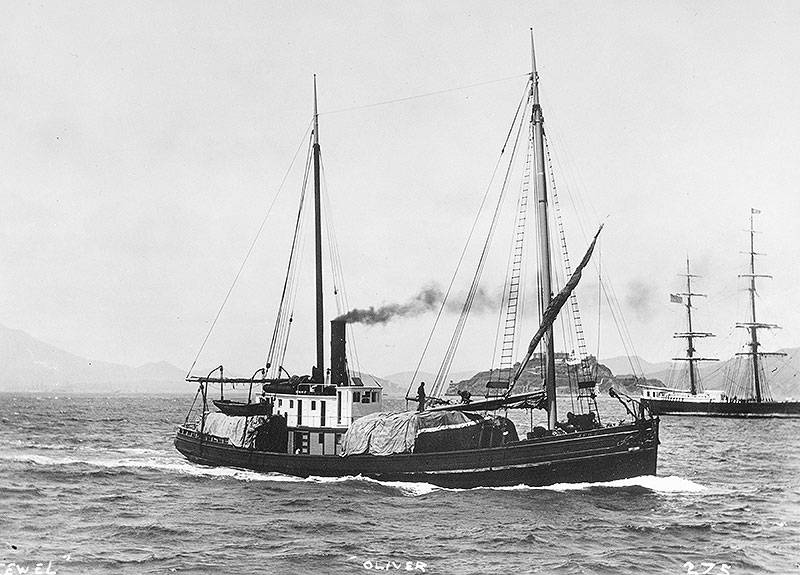

Steam schooner Jewel on the San Francisco Bay, c. 1880s.

Photo: San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park

While the Coast Seaman's Union was growing, steamers came to dominate sailing vessels and the Steamshipman's Union was formed. Rivalry between the two weakened both in their fight against the crimps and shipowners. It was not until July .29, 1891 that the Sailors' Union of the Pacific combined the two, starting the march forward to a new order for American seamen. There were more than four thousand members in that organization, and before one year had passed, the treasury held fifty thousand dollars. The strongest union local in the United States, it made plans to fight the Shipowners' and Coast Boarding Masters' associations. A titanic battle began, one destined to restore to the merchant sailor rights he had not enjoyed since medieval times.

The year 1892 saw East Street the scene of more bloodshed than ever in its stormy career. During the battle for control, crimps and shipowners were as ruthless as the union seamen; police were powerless to check the series of riots, beatings, sabotage, and murder that swept the waterfront. Union men boarded ships and administered terrific beatings to "scabs." Crimps and their runners lurked along the fringes of the Barbary Coast to return the treatment, and every day dawned on lifeless bodies. Militant unionists cut the mooring lines of ships, knocked out the shackles of anchor chains on vessels in the stream, and wrecked the lifeboats and gear of ships hiring non-union crews. Rocks went heaving through the windows of saloons and boardinghouses; the affiliation of waterfront restaurants and grog shops became their greatest denominator.

As tolerant San Francisco took sides, it appeared that the Sailors' Union would win the fight, for the Shipowners' Association, tired of battling, was ready to give up. The sailors' beat-up gangs had overcome the crimps. Then the powerful Manufacturers' and Employers' Association stepped in and took up the cudgels for the shipowners. That organization, with a reputation for breaking unions, waged a more bitter war. By the summer of 1893 the Sailors' Union funds had withered and the men were forced to give up, to take "what they could get."

With this show of weakness the clamps were immediately tightened in an effort to destroy forever the S.U.P.,"for safety's sake." The hated "grade books"(1) came back and wages sank to fifteen dollars a month. The losers were not allowed to forget their defeat.

The sailors' position was made even more uncertain on September 25 when a satchel of dynamite exploded in front of Curtin's non-union saloon and boardinghouse, blowing out the front of the building and killing five. Most of the hundred thousand people who came next day to see broken windows for blocks around, and to examine pieces of the bodies splattered about, blamed the union. A sailor was tried and acquitted; the Sailors' Union claimed it was the work of enemies to discredit them, as it definitely did. No one has ever been proved guilty of blowing up the Curtin building. For the next five years the Sailors' Union was kicked about the waterfront as of old. Sail was definitely pasing and on San Francisco's waterfront its farewell was·the bloody revolt of men who shipped before the mast. With fewer of the old sailors left on which to shanghai men, the crimps sought to shift the old order of brutal treatment, blood money, and the collection of seamen's advanced wages to the new ships . At a low ebb in the life of the Sailors' Union they were successful in some measure. The rights of the sailor, it appeared, would change little in the transition from sail to steam.

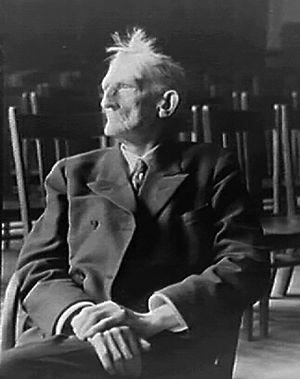

Andrew Furuseth

But though it lay dormant, the union had a strength that could not be corrupted: its strange leader, the lank Norwegian sailor Andrew Furuseth. That honest man, a curiosity with his peculiar mannerisms and his great loyalty, was the sailor's anchor to windward. More a fisherman than a sailor, thirty-year-old Andrew Furuseth had come first to the Coast in a British ship from Calcutta. He was on the Columbia River fishing when the Coast Seaman's Union formed on Folsom Street Wharf. He returned to San Francisco a few months later, joined, and in a year had been elected secretary, a post he held up to the great 1934 strike. Occasionally he quit his job to go fishing, in answer to charges by jealous members that he had "grown fast in his seat"; but always he came back. To no other man would sailors listen as they did to Furuseth.

Andrew Furuseth, c. 1930s

Photo: Online Archive of California

Along the waterfront men were at a loss to explain the assertion: "By God, Furuseth--he's a great man." The nearest explanation was the fumbling: "Well well, he's honest." Andrew could read and write well, at that time enough to disqualify any seaman as honest. Too, he had no use for women and it was certain that no female would make off with the funds of the union. This had happened with a previous secretary, a man more attractive personally than Andrew. Awkward in their presence, often insulting, Furuseth never had anything to do with a woman through his life. Many wondered if he was really a man, and took pains to prove it, for he had a fair and delicate skin which he never needed to shave and his voice was shrill and high.

Furuseth had no friend, man or woman, but he held great power over crowds. To carry a motion or defeat an opposing idea, he had only to threaten resignation. And many times he downed the questioning of his actions by a stock question and statement: “Who's paying you? ... Oh, no one! ... Well, someone should be paying you."

The stormy decade of the nineties saw Andrew arriving early at the Sailors' headquarters on the second floor of a building at the corner of Mission and East streets, now the Embarcadero. The seamen abandoned that hall after the 1906 Fire when the landlord, a Frenchman, doubled the rent. Since that time it has never had a tenant. Furuseth used to leave it late, alone, for his small room at Johnny Walker's place, hard by on Steuart Street. Walker's was one of the "respectable" sailors' boardinghouses and its location was variously known as Finn Alley and Irish Alley because boardinghouses catering to those nationalities lined opposite sides of Steuart Street. Sometimes Furuseth stopped at one of the saloons, for he liked an occasional shot of whisky (though he seldom, if ever, drank too much). At times he went to the theater, but most of his leisure hours were spent reading books of social significance.

A stubborn man, without a sense of humor, and a lonely one, Furuseth devoted his life to the betterment of the man before the mast. Through the nineties was first heard his long speech asserting that the sailor was a"bondsman." Many heard him plead for the removal of the sailor's shackles, and into the Congressional Record went his oft repeated: "We hold up our manacled hands." Andrew's appeal to the heart irked the shipowners. But there was logic behind the melodrama: the sailors were, compared to workers ashore, little better than slaves.

Furuseth left for Washington in 1894 for the first time and brought the sailor's problem to the Government. Soon he was spending the greater part of his time there, putting through legislation.

The Belaying Pin And The Boot

Before leaving San Francisco, Andrew chose a young Scotch sailor, Walter Macarthur, to head the Sailor's powerful organ, the Coast Seaman's Journal, from which was to come one of the sea's most influential documents, the Red Record. This was a story written out of the logs of the grain ships and did for the merchant seaman what Herman Melville's White Jacket had done for the men of the United States Navy.

The Red Record was born in 1895, in the first year of Macarthur's editorship. Sitting in a little office where the bowsprits of ships berthed at East Street nearly reached his window, Macarthur read through back numbers of the Journal, filled with reports of unpunished brutality at sea. Since leaving his home on the Clyde as a boy, the Scotsman (a stocky man with handsome features, dark hair, and a forthright voice) had been a reader and a thinker. Almost half a century later, still living near the waterfront, he recalled how the famous document evolved.

Macarthur had read the laws of the ancients, sea laws first written for the galleys out of Phoenician ports,·nine hundred years before the birth of Christ. A master might strike a seaman once if he did not obey, but on receiving a second blow the man before the mast was allowed to defend himself. Civilization was young then, still unhampered by too many precedents; there was justice in the old law that time had not altered. A single blow was still in order to get action; but nowhere was there reason for reports that a seaman had been "kicked until insensible" or beaten with a belaying pin until "his body was covered with bruises, nose broken, several teeth knocked out and his internal organs ruined."

Because people no more believed such things possible than did another generation credit tales of flogging, keel-hauling, and tricing up, Macarthur began publishing cases of cruelty as a supplement to the Journal. Finally he bound them and had a striking cover made; blood-red, it showed a hand gripping a belaying pin. The brass belaying pin and the boot were to the merchant marine what the cat-o'-nine-tails and gratings had been to the naval ships of Melville's time. The Red Record listed sixty-three cases of unpunished brutality. A few of them follow:

THE RED RECORD ECCE! TYRANNUS

The symbol of Discipline on the American hell-ship

A brief resume of some of the cruelties perpetrated upon American seamen at the present time, 1888 to 1895:Tam O' Shanter, Capt. Peabody. Arrived in San Francisco September 6, 1888. First mate Swain arrested on three charges of cruelty preferred by seamen Fraser, Williams, and Wilson. Captain defended his mate on the ground of incompetent crew; did not say how he came to sail with incompetent men. Mate released on $450 bond. Case still in the courts.

Lewllyn J. Morse, Capt. Lavary. Arrived in San Francisco February 1889. First mate Watski charged by. seaman Arthur Connors with striking him on the head with a pair of handcuffs, imprisonment in the Lazarette and gagging because the complainant was singing. Captain was present during these inflictions, but refused to interfere. Watski released on $500 bonds. Case still pending.

Commodore T. H. Allen, Capt. Merriam. Arrived in San Francisco, April 1889. A seaman McDonald reported that while expostulating against the vile language of the third mate, he was struck several times by that officer, thrown against the rail with such violence that his shoulder was dislocated. The Captain remarked when appealed to "serves you damned well right," and ordered mate to confine McDonald in the carpenters shop. As treatment for his wounds he was given a dose of salts. Another seaman fell sick and was confined with McDonald in the carpenters shop—a combination of hospital and prison. There being only one bunk in the place, the weakest man had to sleep on deck. Diet for the sick man: common ship's fare; medicine: salts. For four days he ate nothing. Finally he died. Interviewed about the matter, the third mate acknowledged McDonald was a good seaman but that he (the third mate) was down on him.

Standard, Capt. Percy. Arrived in San Francisco, October 1889. Seaman E. Anderson went to the Marine Hospital and complained of ill treatment from first mate Martin. One day out of Philadelphia, the first mate knocked Anderson down. Anderson got up and endeavored to expostulate, but was knocked down and kicked until he was insensible. Anderson since has suffered from intense pains in the head and chest and has been subject to fits for the first time in his life. Mate ordered him aloft contrary to the orders of the Captain. Men had to lash him in the rigging to prevent his falling and Anderson laid up and the mate endeavored to haul him on deck. Warrant sworn out for the mate's arrest; mate disappeared and could not be found.

Reuce, Capt. Adams. Arrived in San Francisco, November 1889. Seventeen seamen down with scurvy, one man died from some disease. Rotten and insufficient food was the cause. Every man was in a fearful condition as a result of the ravages of scurvy. Off the Horn men had to work through hail, wind and water on empty stomachs; while some of the men were holystoning the decks they were beaten by the second mate. The latter officer skipped as the Reuce was towing through the Golden Gate. Men will never recover from the disease. Case tried in District Courts and verdict of $3,600 damages awarded seamen.

Sterling, Capt. Goodwin. Arrived in San Francisco, January 1890. Three seamen went to the Marine Hospital with scurvy. All hands had bad and insufficient food and brutal treatment from the officers.

Edward O'Brien, Capt. Oliver. Arrived in San Francisco, February 1890. First mate Gillespie charged with most inhumane conduct. He knocked down the second mate and jumped on his face. Struck one seaman on the head with a belaying pin, inflicting a ghastly wound, then kicked him on the head and ribs, inflicting life marks. He struck another man on the neck with a capstan bar, then kicked him into insensibility. He struck the boatswain in the face because the latter failed to hear an order. Gillespie charged and admitted to bail.

Tam O'Shanter (2), Capt. Peabody. Arrived in San Francisco, July 1893. Charges of the grossest brutality made against second mate R. Crocker (late of the Commodore T. H. Allen). Crocker stands six feet, three inches in height and weighs 260 pounds. He assaulted several seamen. One in particular, Harry Hill, bore nine wounds, five of them still unhealed. A piece was bitten out of his left palm, a mouthful of flesh was bitten out of his left arm, and his left nostril torn away as far as the bridge of the nose. Crocker is reported to have kicked a man from aloft; seaman hit down on deck, Crocker followed and administered a beating, marks of which showed in court. Crocker held in $500 bail. Case tried; usual verdict—acquittal.

M. P. Grace (2), Capt. DeWinter. Arrived in San Francisco, July 1893. Captain DeWinter and second mate charged with cruelty. Case postponed . Crew go to sea. Case called and dismissed for lack of evidence.

Shenandoah, Capt. Murphy. Arrived in San Francisco, October 1893. One seaman, M. Bahr, fell overboard from the royal yard and no effort was made to save him. The Captain acknowledged this but excused himself on the ground of rough weather. Ship had topgallant-sails set. A passenger reports that the food was a revelation to him, being meager in quantity and bad in quality. Cruelty and constant abuse charged to the officers. The captain refused to see these goings on, or to interfere when complained to.

Francis, Capt. Doane. Arrived in San Francisco, October 1893. First mate Crocker (late of Commodore T. H. Allen and Tam O' Shanter), accused of gross brutalities to the crew. Seamen bore marks on their persons when they complained to the commissioner. Crocker arrested and admitted to bail; crew compelled to go to sea in the meantime. Case dismissed for lack of evidence.

Hecla (2), Capt. Cotton. Arrived in San Francisco, April 25, 1894, from Baltimore. Crew complained of brutality. Food scarce and of bad quality. Seaman E. J. Svendenberg charged that the first mate struck him on the head with a belaying pin. On other occasions the officers assaulted the crew, using hammers and marlinspikes. First mate John Cameron and second mate John St. Claire arrested. Case dismissed by U.S. Commissioner Heacock for lack of evidence.

May Flint, Capt. Nickels. Arrived in San Francisco, August, 1895, from Baltimore, Md. The crew charged that brutal treatment had begun before the vessel got underway on the Chesapeake. They asked Captain Nickels to send the police aboard. This the captain promised to do and instead he sent off a gang of crimps who beat and finally terrorized the seamen. During the passage one man, while kneeling at his work, was kicked in the testicles and permanently ruptured. Another man had his face laid bare with a holystone by Captain Nickels. One man was beaten for unavoidably spitting on deck while aloft and another was triced up to the spanker boom for some trifling fault. The seamen were frequently assaulted by Captain Nickels, while at the wheel, and vile names were applied to them as a general thing. Captain Nickels and second mate Knight were examined by U.S. Commissioner Hancock and completely exonerated.

Benjamin F. Packard (2), Capt . Allen. Arrived in San Francisco, October 24, 1895 from Swansea, England. Crew reported that trouble occurred on the vessel while lying in the stream at Swansea. Several seamen attempted to back out, but were terrorized into going aboard. "Cockney" Falconer, able seaman, was sworn at and assaulted while aloft by the second mate, Turner. The man was afterwards put in irons and while in this helpless position was challenged to fight by Captain Allen, and was assaulted by the first mate and carpenter. William Ace, able seaman, was called on deck during his watch below and assaulted. Robert Lewis, able seaman, while clearing the main topmast staysail dropped the clew on deck, and for this he was set upon and beaten by the second mate. Two boys who had shipped as ordinary seamen were constantly ill-treated by the second mate by having their ears pulled and clouted, etc. The second mate assaulted both quartermasters in their watch while they were at the wheel. The crew said they had never clewed up a sail in bad weather without having trouble of some sort. Two members of the crew swore to warrants for the arrest of the second mate and the carpenter. The former disappeared as usual, and the latter was dismissed by U.S. Commissioner Hancock on the ground of "lack of evidence."

Bohemia, Capt. Hogan. Arrived in San Francisco November 11, 1895, from Philadelphia via Rio de Janeiro. Reports the loss of spars and a mutiny of the crew, headed by second mate Eagan. Captain Hogan said that all hands, with the exception of the first mate, refused to work ship and compelled him to put into Rio. Second mate Eagan deserted in Rio, a fact which throws suspicion on the charge of mutiny, and Captain Hogan threatened to have his crew arrested, but did not. The crew on the other hand charged Capt. Hogan with ill-treatment and said that he was responsible for the loss of seaman Frank M. Weston, who was drowned from the jibboom at the time of the vessel's dismasting. The steward recited a specific instance of cruelty when Captain Hogan clubbed him in Rio. Nothing done in the matter.

Susquehanna (2), Capt. Sewall (late of the Solitaire 2). Arrived in San Francisco November 12, 1895, from New York. The crew charged the usual ill-treatment against the Captain. For the arrest of the first mate, Ross on the charges of brutality, beating of seamen, etc., Captain Sewall threatened, that if Ross was convicted, he would have the crew arrested on the charge of mutiny. The case of Ross was heard before U.S. Commissioner Hancock and, as usual, dismissed. Captain Sewall is one of the most notorious brutes in charge of an American ship. This is his fourth appearance in the "Red Record" in less than seven years. He has openly boasted that he would beat his seamen whenever he felt inclined. Well sustained charges of murder have been made against him, but he has gone scot free every time, and once in Philadelphia in 1889, when he was in danger of conviction he "disappeared" for a time and afterwards "healed the wounds" of the complainants with small considerations in cash. His case in the present case is simply a repetition of an old dodge to embarrass the officials.

Routine beating of sailors at sea during 19th century, when sailors were deemed unworthy of protection from involuntary servitude.

"Tomorrow Is Also A Day"

This is sufficient. It was good newspaper copy; the story spread throughout the nation and helped Andrew Furuseth get the Maguire and White Acts passed in Congress. The sailor was on his way to being a "free man."

The turn of the century also brought with it prosperity and at San Francisco came great industrial activity. It was a good time to strike and the year 1901 saw the Sailors' Union of the Pacific out on picket lines with their fellow unions of the City Front Federation. More than half of San Francisco's business stopped; fights, riots, and murder again swept the waterfront. By the following year success for sixteen years of struggle came when the S.U.P. was at last recognized with its first working agreement. Until 1915 there were setbacks; bad times found the shipowners fighting with Negroes, farmers, and college boys; good times saw the seamen abusing their gains. In 1904 Senator Alger of Michigan introduced a bill which became law: "An Act to Prohibit Shanghaiing in the United States." After fifty years of preying on the sailor, the crimps of San Francisco's Barbary Coast were through.

But all this was law and as such could easily be evaded. It was not until 1915 that the Sailors' anchor really held. In that year Congress passed the Seaman's Act, signed March 4 by President Wilson: "An Act to promote the welfare of American seamen in the merchant marine of the United States. . ." At last Jack was free.

The shipowners claimed that the fight had been won by appealing to the heart instead of the brain and that the "terrible slavery" of Furuseth's shackled , downtrodden sailor had been made too much of in Washington. At San Francisco business groups predicted this legislation would mark the end of transpacific shipping; its principal effect would be to drive American ships from the sea. Champions of the act saw "the Dawn of a New Day."

The sailors, lone group to serve their country through the World War without striking, were in strong favor until 1921. Through the hard times they had stuck together, always they remembered Andrew Furuseth's favorite sentence: "Tomorrow is also a day."

(1) The seaman's objection to the grade book, in which was listed his sea service record, was that it could be, and was, used to blacklist him.

Originally Chapter 16 in Golden Gate: The Story of San Francisco Harbor published in 1940 by Tudor Publishing Co., New York