Mission Yuppie Eradication Project: Difference between revisions

(added link) |

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

The second round of posters would spell trouble for Keating, who was arrested while putting them up at 2 am on May 14, 1999, reportedly “covered with paste” (4). He had been put under surveillance that April due to suspicion that he and his group were responsible for various acts of vandalism in the neighborhood. The police were quick to sweep his apartment for anarchist and communist materials, as well as a variety of other items: wrote Keating in 2013, “While I was in custody SFPD cops executed a search warrant on the apartment I shared with my girlfriend and seized my computer, camera equipment, file cabinets, a tape recorder, a mountaineering axe, materials for a 16mm film I was working on — they took everything I’d written, photographed or filmed. They seized more than 80 books, mostly on political themes” (5). Police also found confidential financial information on the Cort family, including social security numbers and bank account information, and on James Ludlow, a retired police officer whose son, also a police officer, had been in charge of reviewing permits. They also came across a book on making acid bombs and an article about the Unabomber. Keating was charged with “malicious mischief” and “terrorist threats,” though these charges were ultimately dropped (6). | The second round of posters would spell trouble for Keating, who was arrested while putting them up at 2 am on May 14, 1999, reportedly “covered with paste” (4). He had been put under surveillance that April due to suspicion that he and his group were responsible for various acts of vandalism in the neighborhood. The police were quick to sweep his apartment for anarchist and communist materials, as well as a variety of other items: wrote Keating in 2013, “While I was in custody SFPD cops executed a search warrant on the apartment I shared with my girlfriend and seized my computer, camera equipment, file cabinets, a tape recorder, a mountaineering axe, materials for a 16mm film I was working on — they took everything I’d written, photographed or filmed. They seized more than 80 books, mostly on political themes” (5). Police also found confidential financial information on the Cort family, including social security numbers and bank account information, and on James Ludlow, a retired police officer whose son, also a police officer, had been in charge of reviewing permits. They also came across a book on making acid bombs and an article about the Unabomber. Keating was charged with “malicious mischief” and “terrorist threats,” though these charges were ultimately dropped (6). | ||

Throughout that summer and fall, the Yuppie Eradication Project received vast amounts of media coverage both nationally and internationally. The project, and Keating in particular as a known radical, had always been quite controversial. Mission District residents responded in starkly different ways: some were utterly horrified at the posters’ threats of violence, especially the yuppie-types Keating wrote so vehemently against. They complained of hate crimes committed against them. Yet Keating’s message also resonated with many Mission District residents long frustrated with the gentrification of their neighborhood. Though often in extreme and divisive terms, he spoke to a deep-rooted feeling of resentment that sat at the very heart of the community. When Keating spoke to the ''New Mission News'' in 1999, he put it this way: ‘“Gentrification is infinitely more violent than anything my friends and I would ever be able to marshal… Violence to me is somebody like Robert Cort, Jr. kicking elderly working class people out of their home where they lived for 33 years. Is anybody going to tell the Ghandi or Cesar Chavez or Martin Luther King schtick to him?” (7). | Throughout that summer and fall, the Yuppie Eradication Project received vast amounts of media coverage both nationally and internationally. The project, and Keating in particular as a known radical, had always been quite controversial. Mission District residents responded in starkly different ways: some were utterly horrified at the posters’ threats of violence, especially the yuppie-types Keating wrote so vehemently against. They complained of hate crimes committed against them. Yet Keating’s message also resonated with many Mission District residents long frustrated with the gentrification of their neighborhood. Though often in extreme and divisive terms, he spoke to a deep-rooted feeling of resentment that sat at the very heart of the community. When Keating spoke to the ''New Mission News'' in 1999, he put it this way: ‘“Gentrification is infinitely more violent than anything my friends and I would ever be able to marshal… Violence to me is somebody like Robert Cort, Jr. kicking elderly working class people out of their home where they lived for 33 years. Is anybody going to tell the Ghandi [sic] or Cesar Chavez or Martin Luther King schtick to him?” (7). | ||

One of the most prominent reactions to the Yuppie Eradication Project’s efforts was a fake pro-yuppie rally about a month after Keating’s arrest. ''SF Weekly'' ran a quarter-page advertisement for a “Stop the Hate” rally to be held on June 6, 1999 at Dolores Park. Reporters and two hundred anti-gentrification counter-protesters filled the park instead. Keating and his group waved signs with sarcastic slogans like “Give greed a chance,” “Poor people suck,” and “Make lofts not war.” The event was ultimately revealed to be a prank put on by the ''SF Weekly'' editorial staff—with the joke ultimately falling on yuppies, who complained that their fears of persecution were being mocked. | One of the most prominent reactions to the Yuppie Eradication Project’s efforts was a fake pro-yuppie rally about a month after Keating’s arrest. ''SF Weekly'' ran a quarter-page advertisement for a “Stop the Hate” rally to be held on June 6, 1999 at Dolores Park. Reporters and two hundred anti-gentrification counter-protesters filled the park instead. Keating and his group waved signs with sarcastic slogans like “Give greed a chance,” “Poor people suck,” and “Make lofts not war.” The event was ultimately revealed to be a prank put on by the ''SF Weekly'' editorial staff—with the joke ultimately falling on yuppies, who complained that their fears of persecution were being mocked. | ||

Revision as of 15:29, 8 August 2024

Historical Essay

by Eva Knowles, 2024

Graffiti on the walls of lofts near 21st and Harrison in April 1999, signed by the Mission Yuppie Eradication Project (MYEP).

Photo: New Mission News, May 1999

| The Mission Yuppie Eradication Project, which began in the summer of 1998, received national and international media coverage for its calls for direct action protest against dot.com-era Mission District gentrifiers. Its posters implored property destruction of “yuppie” cars and businesses, leading to fierce debates about both the place of newcomers and what constitutes an effective strategy against gentrification. |

The influx of tech workers to San Francisco during the dot.com era dealt a heavy blow to the Mission District. As “yuppies” moved in, rents skyrocketed and working-class people were squeezed out. Expensive restaurants popped up along Valencia Street and “live-work” lofts became constructions of choice in the neighborhood while longtime Mission District residents faced eviction with no place to go.

How to resist? Various groups formed in order to lobby for change, such as the Mission Anti-Displacement Coalition (MAC) and the Coalition for Jobs, Arts, and Housing. Then, in 1998, a markedly different approach rose to the surface: posters calling for destruction of yuppie property began to appear around the Mission District.

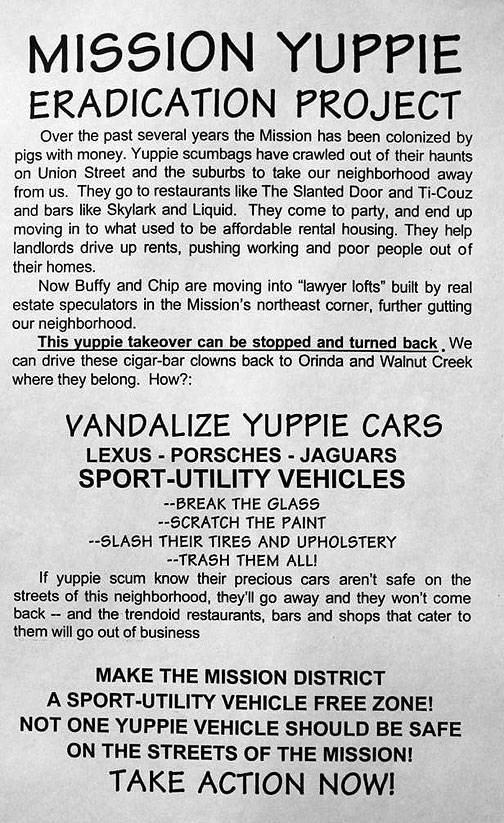

The Mission Yuppie Eradication Project’s first poster, put up in 1998.

A man named Kevin Keating, then going by the pseudonym Nestor Makhno, was behind the project. Keating, then in his late thirties, worked as a mailroom clerk at an architectural firm in addition to being a writer and direct action protester, though his activism had previously taken place in areas outside the Mission District. He likely chose his pseudonym to honor the Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary who took property from landlords and redistributed it to peasants before his taking part in the Russian Revolution. By the summer of 1998, Keating had been living in the Mission District for just over a decade, and during that period had witnessed the changes occurring in the neighborhood.

Keating and a small group wheat-pasted roughly 1100 posters between the summer of 1998 and early 1999. In both an interview with author Rebecca Solnit and his own article published in 2013, Keating attributed the success of the first series of posters to the simplicity of their message. His aim was to describe gentrification in clear terms—without using the word “gentrification” and avoiding Marxist buzzwords. Keating also cited his targeting cars as inciting a reaction: “Targeting cars drew attention to the problem of displacement like nothing else could because nothing is more important to an American’s sense of who they are in the world than their car” (1).

The group called themselves the Mission Yuppie Eradication Project and were sometimes referred to as MYEP or YEPies—the latter particularly by the media. Much of the power of the Yuppie Eradication Project was in its mystery: when asked how big his group was by the New Mission News, Keating said that it was “more than two and less than fifty” (2).

Despite provoking some level of anxiety among the wealthy, expensive car-owning population in the Mission District, the posters were more of a media stunt than a real call for violence. There was no mass destruction of cars after this first wave of posters; they instead stirred up debate as word of the project spread through the news.

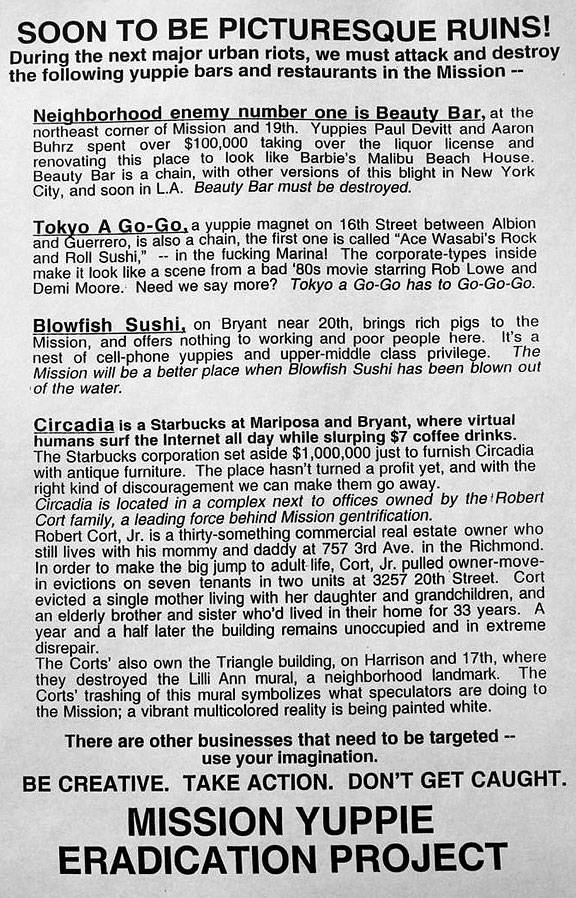

The Mission Yuppie Eradication Project’s second poster, put up in 1999.

The second round of posters went up in 1999. The title, “Soon to be Picturesque Ruins,” was a reference to graffiti on the walls of the Stock Exchange during the May 1968 protests in Paris. This poster directly called out businesses in the Mission District and was printed in Spanish as well as English, unlike the first posters which were only in English.

Keating’s message was certainly radical—yet the sentiment was shared. A satirical article appeared around the same time in the New Mission News, highlighting Beauty Bar in particular as a symbol of gentrification: “Nowhere is the contrast between the Mission’s depressing past and its exciting future more apparent than outside Beauty Bar's doors. Outside; a motley collection of drug addicts, gangbangers, day laborers and other losers. Inside; the buzz of stimulating conversation as the Mission’s young professionals trade ideas and formulate the corporate visions that will shape the next century… When I compare the hip sophistication of the venue and its clientele with the criminality, ugliness and decay that surround them, I can't help but feel a tinge of pride at being part of a great movement of urban pioneers” (3).

As with the first series, the posters functioned mainly as a media stunt. However, Beauty Bar and Tokyo Go-Go both saw a degree of vandalism. “Leave the Mission or else” was graffitied onto the former, while the latter was plastered with signs that said “Target the Yuppies.”

Notably, this second series of posters also called out individual actors in gentrification; namely, the Cort family, who in Keating’s opinion had played a large role in the neighborhood takeover. Their painting over the “Lilli Ann” mural by Jesus “Chuy” Campusano at 17th and Harrison had stirred controversy; then, real estate agent Robert Cort Jr. encouraged even more when he bought a house on 20th Street, evicted the families living there through owner-move-in legislation, and then left it empty.

The second round of posters would spell trouble for Keating, who was arrested while putting them up at 2 am on May 14, 1999, reportedly “covered with paste” (4). He had been put under surveillance that April due to suspicion that he and his group were responsible for various acts of vandalism in the neighborhood. The police were quick to sweep his apartment for anarchist and communist materials, as well as a variety of other items: wrote Keating in 2013, “While I was in custody SFPD cops executed a search warrant on the apartment I shared with my girlfriend and seized my computer, camera equipment, file cabinets, a tape recorder, a mountaineering axe, materials for a 16mm film I was working on — they took everything I’d written, photographed or filmed. They seized more than 80 books, mostly on political themes” (5). Police also found confidential financial information on the Cort family, including social security numbers and bank account information, and on James Ludlow, a retired police officer whose son, also a police officer, had been in charge of reviewing permits. They also came across a book on making acid bombs and an article about the Unabomber. Keating was charged with “malicious mischief” and “terrorist threats,” though these charges were ultimately dropped (6).

Throughout that summer and fall, the Yuppie Eradication Project received vast amounts of media coverage both nationally and internationally. The project, and Keating in particular as a known radical, had always been quite controversial. Mission District residents responded in starkly different ways: some were utterly horrified at the posters’ threats of violence, especially the yuppie-types Keating wrote so vehemently against. They complained of hate crimes committed against them. Yet Keating’s message also resonated with many Mission District residents long frustrated with the gentrification of their neighborhood. Though often in extreme and divisive terms, he spoke to a deep-rooted feeling of resentment that sat at the very heart of the community. When Keating spoke to the New Mission News in 1999, he put it this way: ‘“Gentrification is infinitely more violent than anything my friends and I would ever be able to marshal… Violence to me is somebody like Robert Cort, Jr. kicking elderly working class people out of their home where they lived for 33 years. Is anybody going to tell the Ghandi [sic] or Cesar Chavez or Martin Luther King schtick to him?” (7).

One of the most prominent reactions to the Yuppie Eradication Project’s efforts was a fake pro-yuppie rally about a month after Keating’s arrest. SF Weekly ran a quarter-page advertisement for a “Stop the Hate” rally to be held on June 6, 1999 at Dolores Park. Reporters and two hundred anti-gentrification counter-protesters filled the park instead. Keating and his group waved signs with sarcastic slogans like “Give greed a chance,” “Poor people suck,” and “Make lofts not war.” The event was ultimately revealed to be a prank put on by the SF Weekly editorial staff—with the joke ultimately falling on yuppies, who complained that their fears of persecution were being mocked.

The Yuppie Eradication Project’s third and final poster series came about in 2000, this time opposing condo development: “Here Are a Few Ways to Welcome Rich People to the Mission…” These “ways” included pouring dirt into their gasoline tanks; perforating tires and radiators with ice picks; and using sponges to stop up drains in yuppie bars and restaurants. According to Keating, the cartoon-like images on the poster were copied from the CIA Nicaraguan Contra sabotage manual of the 1980s, with slight modifications. The poster ended this way: “Yuppies—get the fuck out of our neighborhood!” (8).

The project largely disappeared from the media after that. In 2013, Keating wrote an essay in which he analyzed the project’s success. Among his points was his opinion that although it had a strong initial impact, the project lacked follow-through. He went on to provide a list of concrete actions he could have pursued, including directly targeting individuals; creating an action group; and organizing a public assembly and/or demonstration (9).

Keating was right in that the Yuppie Eradication Project alone could not stop gentrification of the Mission District. Throughout the 2000s and continuing today, more and more families and businesses have been displaced as the cost of housing has increased. However, the Yuppie Eradication Project stands as an emblematic chapter in the broader narrative of gentrification resistance. Its very existence sheds light on the lengths to which individuals and groups may go to voice their dissent. To Keating, what was most valuable about the Yuppie Eradication Project was the role it played in creating a culture of direct action. As it professed on its posters: “Be creative. Take action. Don’t get caught.”

Notes

1. The artist formerly known as Nestor Makhno. “A Critique of San Francisco’s Mission Yuppie Eradication Project.” The Anarchist Library, December 11, 2013. https://theanarchistlibrary.org

2. vmiller. “The YEPies take on the gentry.” New Mission News, November 1998: 10. https://archive.org.

3. Silicon Satan. “Beauty Bar: the way things ought to be.” New Mission News, July 1999: 9. https://archive.org.

4. Van Derbeken, Jaxon. "Battle Over Gentrification Gets Ugly in S.F.'s Mission - Anarchist arrested, charged with making threats." The San Francisco Chronicle, June 7, 1999: A1. NewsBank: America's News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.

5. Ibid.

6. vmiller. “Gentro Blues.” New Mission News, July 1999: 4. https://archive.org.

7. vmiller, 1998.

8. "Here are a few ways to welcome rich people to the Mission." In the digital collection Political Posters, Labadie Collection, University of Michigan. University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. Accessed July 29, 2024. https://quod.lib.umich.edu.

9. The artist formerly known as Nestor Makhno, 2013.