Inspired and Possessed: San Francisco Women Newspaper Publishers: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

Though Pitts Stevens evoked certain ideals of the Enlightenment, her interest in human rights did not extend past white women of early American descent. "Think of it!" she wrote, "Hans, Sambo, Patrick, Young Chung, who never read a line of the Constitution, or a word of the Declaration, making laws for the lineal daughters of the framers of that Constitution, the signers of that Declaration." She went on to ask, "would the gentlemen who tell us to wait until the Negro is safe, before we claim suffrage, be willing to stand aside themselves, and trust their interests in like hands?"(19) Her racism echoed the well-documented response of leading women reformers like Anthony and Stanton, who were especially bitter over what they interpreted as betrayal by the Abolitionists, who had failed to support the inclusion of women in the battle over passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. | Though Pitts Stevens evoked certain ideals of the Enlightenment, her interest in human rights did not extend past white women of early American descent. "Think of it!" she wrote, "Hans, Sambo, Patrick, Young Chung, who never read a line of the Constitution, or a word of the Declaration, making laws for the lineal daughters of the framers of that Constitution, the signers of that Declaration." She went on to ask, "would the gentlemen who tell us to wait until the Negro is safe, before we claim suffrage, be willing to stand aside themselves, and trust their interests in like hands?"(19) Her racism echoed the well-documented response of leading women reformers like Anthony and Stanton, who were especially bitter over what they interpreted as betrayal by the Abolitionists, who had failed to support the inclusion of women in the battle over passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. | ||

Along with publishers Schenck and Carrie Fisher Young of the ''Woman's Pacific Coast Journal'', Pitts Stevens was among the 3,300 signers of the CWSA petition for woman suffrage to the California State Legislature in 1870. For Pitts Stevens, publishing a newspaper provided a forum for her reform energies. While suffrage might have been the question of the age, she also worked to find pragmatic and immediate solutions to women's labor and working conditions. She actively trained and hired women to set type for her newspaper. She also promoted the new [Women’s Co-operative Printing Union|Women's Co-operative Printing Union (WCPU)]], a print shop begun in 1868 by Agnes B. Peterson, and she worked with Peterson to make the shop economically viable. | Along with publishers Schenck and Carrie Fisher Young of the ''Woman's Pacific Coast Journal'', Pitts Stevens was among the 3,300 signers of the CWSA petition for woman suffrage to the California State Legislature in 1870. For Pitts Stevens, publishing a newspaper provided a forum for her reform energies. While suffrage might have been the question of the age, she also worked to find pragmatic and immediate solutions to women's labor and working conditions. She actively trained and hired women to set type for her newspaper. She also promoted the new [[Women’s Co-operative Printing Union|Women's Co-operative Printing Union (WCPU)]], a print shop begun in 1868 by Agnes B. Peterson, and she worked with Peterson to make the shop economically viable. | ||

Peterson had launched the print shop shortly after her arrival in San Francisco in response to her inability to find employment as a compositor during Typographical Union no. 21's ban on hiring women. It was not until 1870, when the printers' union staged an eleven-day strike against wage deflation in the newspaper business—and lost—that union shops finally hired women compositors. By the time of the strike, through the efforts of Lester, Pitts Stevens, and Peterson, there was a sizable number of trained female compositors in the city. ''The Call'', desperate to meet its deadline, hired some of these women compositors, was pleasantly surprised with the quality of their work, and wrote about it in the next edition.(20) The ban on women working for union newspapers, one of the most lucrative positions available to compositors, was finally broken in San Francisco. | Peterson had launched the print shop shortly after her arrival in San Francisco in response to her inability to find employment as a compositor during Typographical Union no. 21's ban on hiring women. It was not until 1870, when the printers' union staged an eleven-day strike against wage deflation in the newspaper business—and lost—that union shops finally hired women compositors. By the time of the strike, through the efforts of Lester, Pitts Stevens, and Peterson, there was a sizable number of trained female compositors in the city. ''The Call'', desperate to meet its deadline, hired some of these women compositors, was pleasantly surprised with the quality of their work, and wrote about it in the next edition.(20) The ban on women working for union newspapers, one of the most lucrative positions available to compositors, was finally broken in San Francisco. | ||

Revision as of 19:37, 24 August 2024

Historical Essay

by Anne M. Breedlove

Originally published in California History magazine, Vol. 80, No. 1, Spring 2001, pp. 48-63.

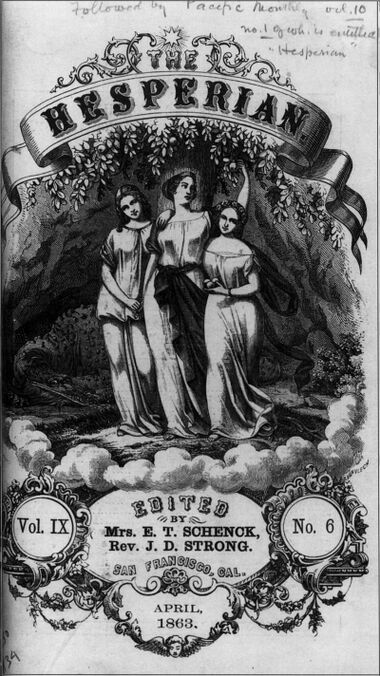

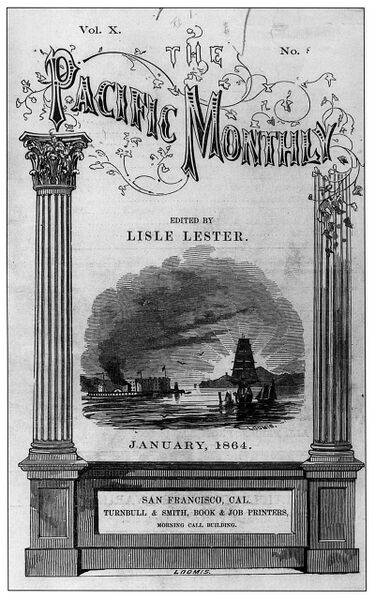

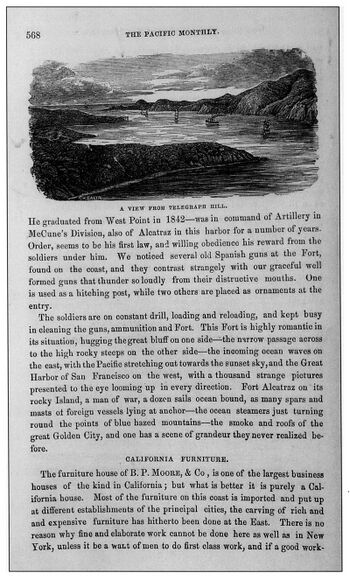

The Hesperian, one of the longest running newspapers published by a woman, had four successive owners or co-owners. The last among them, Reverend J. D. and Mrs. M. D. Strong, changed its name to The Pacific Monthly shortly before selling it to Lisle Lester in 1863.

Courtesy The Bancroft Library

San Francisco was an entrepreneur's dream in the decades after the Gold Rush.(1) Many migrants discovered that if they could not make a fortune panning gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills they might not do badly in a city with a booming population. The newspaper business was a venture that enticed many educated and aspiring individuals: just a decade after the discovery of gold, San Francisco had thirty seven publications.(2) Of those, twelve were dailies (five days a week) and only two published seven days a week. By 1884 there were 114 periodicals published in San Francisco, including 14 dailies, 65 weeklies, and 22 monthlies.(3)

Most who tried to make a living in the newspaper business soon discovered it did not prove to be an easy venture to master or maintain. Most nineteenth-century newspapers were of short duration; few, in fact, lasted more than two or three years. Even with the explosive growth San Francisco experienced in the decades after the Gold Rush, the financial status of most periodicals was precarious at best. The publishing industry, like most businesses, was a wide open field in mid-nineteenth-century San Francisco. Competent labor was scarce and consequently wages were relatively high. The lure of gold drove up wages as businesses were forced to offset the temptation of the Mother Lode in order to retain a workforce. In this environment it was easier for enterprising women to gain employment in fields that were all but closed to them in more established cities back east.

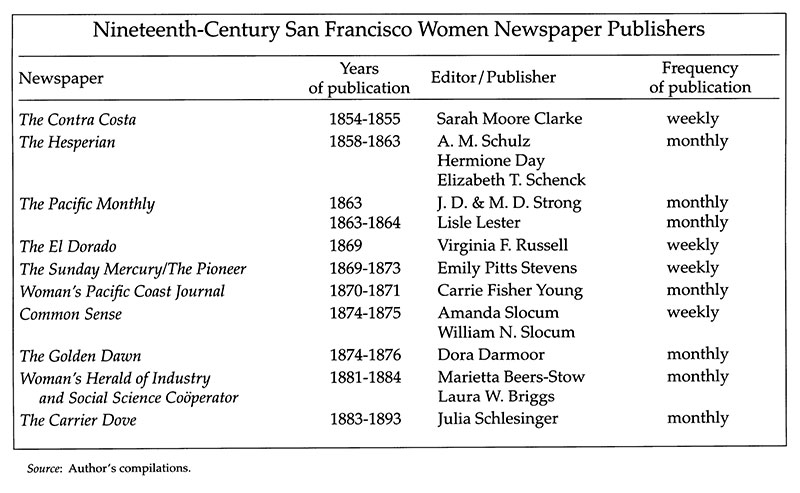

Between 1854 and 1893, ten of these newspapers had fourteen different women publishers or editors. Of the ten, only four stayed in business longer than two years.(4) For that era, these fourteen women were a distinctive subset of San Francisco's publishing industry. Their newspapers were decidedly different in tone and scope than their more formidable competitors, but as a group the women's periodicals shared predictable similarities. They all marketed their periodicals primarily to the female reader, regularly covering articles on housekeeping, home making, and child raising. Many published travel accounts, particularly of trips getting to and exploring California and accounts of California's exotic—by eastern standards—flora and fauna. While most included general-interest articles on the arts and sciences, religion, and occasionally labor relations, all used their newspapers to advocate a change in the status of women. Committed to improving women's "lot," this group of publishers chafed under the restrictions and codes women faced in Victorian America. Whether stressing labor issues, suffrage, temperance, or religion, they all used their newspapers as vehicles for change and improvement. For example, most of them agitated for equal educational opportunities for girls and boys, equal wages for equal work, and the right for women to vote, although they disagreed on the best way to attain the vote.

Newspaper work was one of several avenues of employment available to women with printing skills. Roger Levenson, author of Women in Printing in Northern California, documented 282 women known to have worked at all skill levels in the printing industry in Northern California between 1857 and 1890. While his monograph was a broader enterprise than the specific focus of this article, his research also provided fundamental biographical information on many of the fourteen women in this study.(5) The majority of women employed in the nineteenth-century printing industry worked in the bindery, a part of the production process that had become feminized, partly because of its association with sewing and needle arts. Women also made inroads into type composition, where it was believed that women's nimble hand-eye coordination and the absence of any requirement for physical strength made this job suitable for women. Like their eighteenth-century forebears, most nineteenth-century female compositors first learned their skills in family-run shops. Very few women did presswork, partly because the strength required made it taboo for women.

Although the job descriptions and responsibilities of editors and publishers are quite distinct today, in the pre-industrialized newspaper business of the nineteenth century the two positions and titles were often interchangeable. While all of the women in this study served in an editorial capacity, some also had sole responsibility for printing, publishing, and marketing activities. Others shared those production chores. By examining the content of their newspapers, then, historians can better understand women's involvement in the social, political, and economic development of San Francisco and the West. A voluminous body of research conducted during the past several decades demonstrates the ways women participated in the political, economic, and social fabric of society despite being barred from the ballot box.(6) These women and their newspapers can also help to clarify ways in which California women participated in political discourse before they gained the vote in 1911.

Several of these pioneering publishers helped establish women's rights organizations in California after the Fifteenth Amendment, passed in 1870, denied women the vote. Some had been involved in reform in the East. Emily Pitts Stevens, for example, had made the acquaintance of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton before her arrival in California. It was Pitts Stevens who brought Anthony and Stanton to California in 1871 to campaign on behalf of women's suffrage. Abigail Duniway, leader of Oregon's suffrage movement, was an editor on Pitts Stevens's newspaper, The Pioneer. After visiting Pitts Stevens in San Francisco, Duniway established her own newspaper in Oregon, the New Northwest.(7) Marietta L. Beers-Stow, publisher of the Woman's Herald of Industry and Social Science Cooperator, had been active in reform movements in New York where she gained valuable expertise that she applied in California. Elizabeth T. Schenck, editor of The Hesperian and the first president of the California Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA), was also the first vice president for California of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). Tension between two different contingents within the CWSA over whether to affiliate with the NWSA or American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) developed shortly after the CWSA was established in 1870. Schenck wrote to Stanton for advice, who recommended the CWSA "cooperate with all societies having for their object the enfranchisement of woman."(8) As a result, the CWSA voted at their first convention to remain independent of all other associations for one year. Clearly, the experience of suffrage leaders in the East proved a valuable resource for the early women's rights organizations in the West.(9)

The personal and biographical information on many of these publishers is sparse. Not surprisingly, almost all were recent arrivals in California, some came here with the express intention of working in printing or publishing. Many moved about before coming to California, and others arrived as part of that large cohort of people who responded to the possibility of opportunity and adventure the West offered. Most acquired their knowledge of printing before arriving in San Francisco and quickly put their energies into finding suitable employment for their skills. Like editors everywhere, these women held strong opinions on the leading issues of their day, made a point to get those issues in print, and occasionally found themselves involved in contentious disputes.

Sarah Moore Clarke became the first known woman editor in California when her newspaper, The Contra Costa, debuted in September of 1854. Its short life of only one year, in her case due to ill health, was a portent of the difficulties all the others would face. The next newspaper to be published by a woman, The Hesperian, lasted five years from 1858 to 1863 and had four female editors in succession. It was begun by A. M. Schulz as a woman's literary magazine. Hermione Day followed and quickly put her personal stamp on the paper by shifting Schulz's original focus on entertainment to labor issues and working conditions. "Look at the employments vouchsafed to our women. Look at their pay, when they labor diligently and faithfully all their lives long, poor creatures, in the hope of saving a little for the day of sorrow-that they may not be obliged to marry."(10) The newspaper's third editor, Elizabeth T. Schenck, found herself in extreme financial difficulties and brought in another editor, the Reverend J.D. Strong, to help her keep the paper afloat. Schenck soon sold it to Strong and his wife, Mrs. M.D. Strong. During their short tenure the Strongs returned the newspaper to financial stability and changed its name to The Pacific Monthly. Late in 1863 the Strongs sold the newspaper to one of the most colorful women in this study, Lisle Lester.

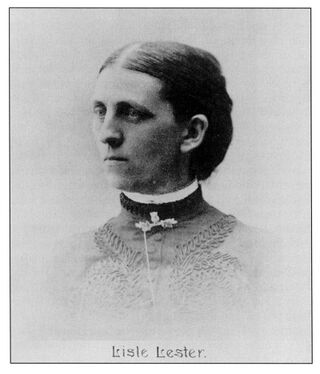

Lisle Lester

Lester is one of the few members of this small coterie of publishers who left a sizeable historical record beyond the content of her newspaper. As an educated, middle-class woman who for a time had to support herself, she is also representative of the group. Born Sophie Emmeline Walker in 1837 in New Hampshire, Lester's family moved to Wisconsin when she was six. She enrolled at the age of sixteen in Lawrence University, in Appleton, Wisconsin, one of the few colleges that admitted women in the 1850s. She left college, however, to pursue a career in journalism. Lester learned to set type, became involved in several publishing ventures in Wisconsin, and soon married a teacher, Isaac L. Bloomer, in 1858. By 1861, she divorced Bloomer and, for reasons now unknown, changed her name to Lisle Lester.

Under Lisle Lester's direction, The Pacific Monthly became a politically oriented newspaper. She tried to keep the articles timely and promoted acceptance of women in the industry.

Courtesy Bancroft Library

During the Civil War, Lisle Lester found ample work as a typesetter because so many male compositors went off to fight. While thus employed she was soon familiar with the gendered conflicts in the printing industry, exemplified by an unsuccessful strike by men to prevent the hiring of women compositors. As a self-supporting woman, she was directly affected by the conflict, and began to help shape the highly political focus of her newspaper. Lester fought for change in women's employment opportunities. By February of 1864, three months after assuming editorship of The Pacific Monthly, she used her editor's column to take on the Typographical Union no. 21 in San Francisco for its refusal to admit women. "We wish to place before our readers that they may see for themselves the unjust notions and rule of those who persist in keeping a woman, out of a printing office on the ground, 'of inability to give her work, because a Typographical Union controls them and their business."'(11) Having already successfully fought sexist practices with the printer's union in Minnesota before moving to San Francisco, Lester excoriated those print shops too timid to contest the union and hire capable women compositors. "Why is it Printers have made for themselves such absurd and ridiculous rules in regard to female labor?" she asked.(12) Lester and Schenck attempted to establish a Female Typo graphical Union in 1864 in response to Local 21's boycott of women workers, but they failed. Juggling other interests and activities, neither woman was able to give enough attention to the fledgling enterprise to nurture it into a viable competitor with the formidable no. 21.

This page from the Pacific Monthly contains an interior illustration, an expensive and thus infrequent feature of small publications. This "View from Telegraph Hill," by G. H. Baker, captures a scene that would have interested readers near and far: San Francisco Bay, looking west to the Pacific Ocean, with Fort Point visible at the left.

Source: California Historical Society, FN-32467.

Other ventures devoted to promoting women's employment opportunities in San Francisco appeared. The El Dorado Publishing Association incorporated in early 1869 with the express purpose of printing a newspaper "devoted to the interests of the Women of the Pacific Coast." More than two hundred association members included prominent, established merchants of both sexes, and the funding and support they contributed to this venture was impressive. The managing board included three men and three women, including Virginia F. Russell as editor. From its first issue, the paper was fraught with conflicting messages from its first issue. An article titled "The Woman's Paper," and signed by “Father," noted: "The time has come when the elevation of woman must and will be a subject of not only thought, but of deep, earnest advocacy by the good and philanthropic everywhere-and it is by the Printing Press that this great end is to be achieved."(13) Yet, in this same issue editor Russell announced to the public that The El Dorado "is what is called a 'woman's paper'—i.e., a paper conducted by women, and devoted to the interests of the women of the Pacific Coast. It is NOT and will NOT be an advocate of 'Womans Rights,' as enunciated by certain hot-headed dames whose zeal runs away with their discretion."(14) The newspaper did not survive to its one-year anniversary, however, perhaps because its large membership held conflicting visions of its purpose.

The same year the El Dorado was launched, the Sunday Mercury was taken over by editor Emily Pitts Stevens. Born into a middle-class New York family, Pitts Stevens had moved to San Francisco in 1865 to teach at a girls' school. Having learned how to set type, she turned to newspaper work after two years of teaching. When she assumed the editorship of The Sunday Mercury in January of 1869, she, like Day and Lester before her, changed the paper's focus to match her interests more closely. Among her new regular columns were "Woman's Suffrage," "Good Words for Women," and "Facts for Women." It took Pitts Stevens a few months to remake the entire paper, but before long The Sunday Mercury routinely carried articles with headlines like: "The Question of the Age," "What is Women's Sphere?" and "The Next Great Question of the Time."(15) "It must be clear," she wrote, "to every far-seeing mind that the subject of woman suffrage will be the next great question entering into national politics."(16) By November she renamed the paper The Pioneer, proudly noting on the masthead that it was "devoted to the promotion of human rights."(17) Advocating the feminization of politics, she wrote that suffrage would not be "the work of a day ... We do not advocate female suffrage in itself, but only as a means to secure the higher and nobler objects which we advocate."(18)

Though Pitts Stevens evoked certain ideals of the Enlightenment, her interest in human rights did not extend past white women of early American descent. "Think of it!" she wrote, "Hans, Sambo, Patrick, Young Chung, who never read a line of the Constitution, or a word of the Declaration, making laws for the lineal daughters of the framers of that Constitution, the signers of that Declaration." She went on to ask, "would the gentlemen who tell us to wait until the Negro is safe, before we claim suffrage, be willing to stand aside themselves, and trust their interests in like hands?"(19) Her racism echoed the well-documented response of leading women reformers like Anthony and Stanton, who were especially bitter over what they interpreted as betrayal by the Abolitionists, who had failed to support the inclusion of women in the battle over passage of the Fifteenth Amendment.

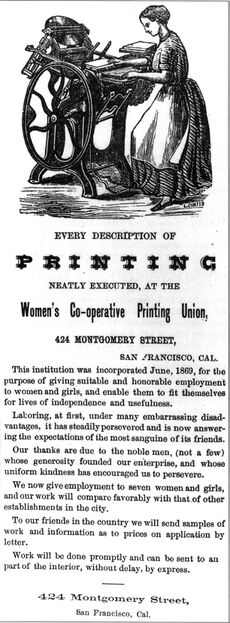

Along with publishers Schenck and Carrie Fisher Young of the Woman's Pacific Coast Journal, Pitts Stevens was among the 3,300 signers of the CWSA petition for woman suffrage to the California State Legislature in 1870. For Pitts Stevens, publishing a newspaper provided a forum for her reform energies. While suffrage might have been the question of the age, she also worked to find pragmatic and immediate solutions to women's labor and working conditions. She actively trained and hired women to set type for her newspaper. She also promoted the new Women's Co-operative Printing Union (WCPU), a print shop begun in 1868 by Agnes B. Peterson, and she worked with Peterson to make the shop economically viable.

Peterson had launched the print shop shortly after her arrival in San Francisco in response to her inability to find employment as a compositor during Typographical Union no. 21's ban on hiring women. It was not until 1870, when the printers' union staged an eleven-day strike against wage deflation in the newspaper business—and lost—that union shops finally hired women compositors. By the time of the strike, through the efforts of Lester, Pitts Stevens, and Peterson, there was a sizable number of trained female compositors in the city. The Call, desperate to meet its deadline, hired some of these women compositors, was pleasantly surprised with the quality of their work, and wrote about it in the next edition.(20) The ban on women working for union newspapers, one of the most lucrative positions available to compositors, was finally broken in San Francisco.

Eliza G. Richmond was manager of the Women's Co-operative Printing Union from the time of its incorporation in 1869. Neither publisher nor editor herself, Richmond's successful operation of the shop for eighteen years was no small feat in the competitive and restricted newspaper market.

Courtesy The Bancroft Library

It was Pitts Stevens's decision to bring in Eliza G. Richmond as manager in 1869. By 1872 Pitts Stevens relinquished any executive responsibility for the firm to Richmond, who successfully managed the WCPU for the next eighteen years, from 1872 to 1890. During her tenure Richmond made the WCPU an important competitor for print work in San Francisco, and worked with leading women activists such as Pitts Stevens, Young, and Amanda Slocum to provide opportunities to women who wanted to enter the field and quality work to anyone willing to risk hiring women printers. The sizeable amount of printed ephemera in public and private collections is testament to Richmond's and the WCPU's success.

The Women's Co-operative Printing Union was a major training site for women wishing to learn composing and printing skills in San Francisco. This ad, describing their struggles and achievements and offering samples of their work, ran in Carrie Fisher Young's newspaper, the Woman's Pacific Coast Journal, in 1870.

Courtesy The Bancroft Library

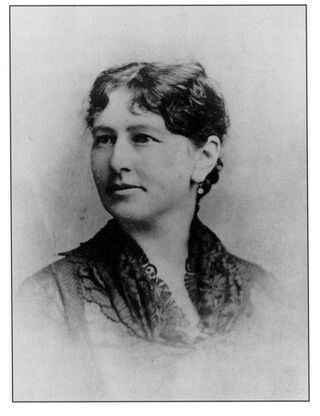

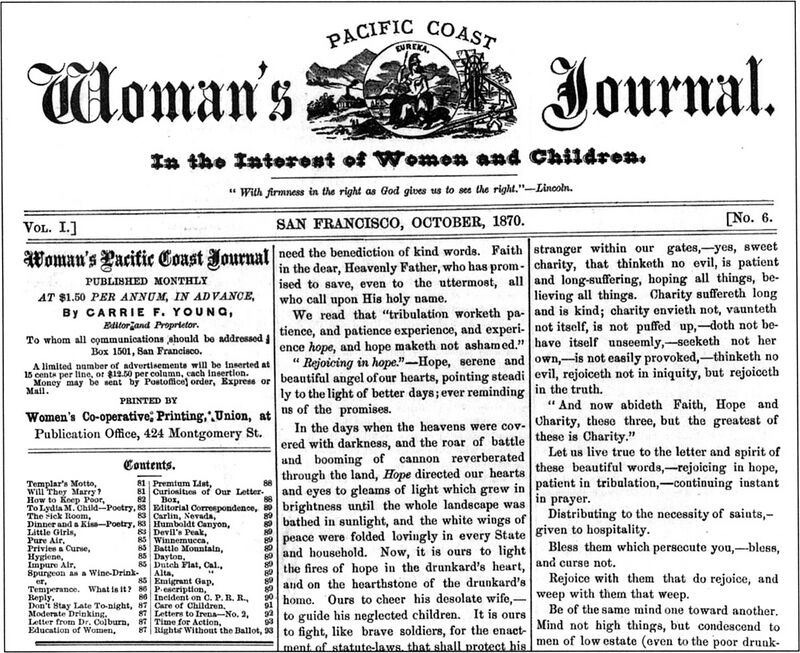

While Pitts Stevens focused her efforts on political and labor reform, another new publisher on the scene focused on moral reform. Carrie Fisher Young's stewardship of the Woman's Pacific Coast Journal (WPCJ) exemplified the responsibility many women felt as upholders of moral standards. With the debut of Young's newspaper there was a noticeable shift in content and emphasis of San Francisco's women-run newspapers. The WCPJ became the first of the papers to convey a strong religious tone and all of the subsequent newspapers followed suit, though they differed on the kind of religious ideas they embraced. Young hired the WCPU to print her newspaper and inserted a quotation by Abraham Lincoln in her paper's masthead: "With firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right," reflecting her desire to address social inequities and her belief in the right of women to shape public sentiment.(21) Suffrage, temperance, education, and labor conditions were constant themes. She wrote that her paper was "devoted to the advocacy of principles and practices which conduce the good order of society and the well-being of individuals."(22)

Young published articles on the difficulties women faced in finding jobs that paid a living wage. She believed that financial independence and moral rectitude were linked, and that women who were unable to support them selves because of low wages or a lack of skills were more likely to lead immoral, unhealthy lives. She noted and commended the progressive attitude of newspaper publisher James J. Owen's San Jose Mercury in employing women compositors and ran a column, "What Can Girls Do?" that gave young women advice on how to chose a profession.(23) Like Lester and Beers-Stow, Young traveled throughout the West in support of reform causes, especially temperance and women's suffrage.(24)

Where Lester and Pitts Stevens placed strong emphasis on women's political and economic rights, Young's paper carried a more strident reforming impulse, preaching clean living and wholesome values. Others, while advocating a pro-suffrage outlook, also incorporated ideas many would consider radical. Amanda Slocum, for example, used Common Sense to champion a "free thought" philosophy that many found morally licentious. Slocum ran numerous articles in support of free-love advocate Victoria Woodhull, and kept track of Woodhull's receptions as she traveled throughout the U.S. It did not take a great deal in Victorian America for these activist women to incur the disapprobation of the mainstream. Woodhull's support of one standard of morality for men and women elicited an outpouring of condemnation from the mainstream press.

Carrie Fisher Young worked with Elizabeth T. Schenck and Emily Pitts Stevens in the California Women's Suffrage Association. Her newspaper, the Woman's Pacific Coast Journal, was printed by the Women's Co-operative Printing Union. Published monthly, an annual subscription cost $1.50, paid in advance.

Courtesy The Bancroft Library

While Amanda Slocum was more adept than Pitts Stevens in avoiding the limelight for her unorthodox beliefs, the two women had much in common. Both were active in the CWSA, both published their own newspapers and used them to promote fair wages for working women. They both taught printing skills to other women. Yet they divided over the issue of free love just as national suffrage leaders were divided by the impact of Woodhull's message. The fallout from Woodhull's ideas reveals the obstacles middle class women faced when their efforts challenged conventional standards. Pitts Stevens, in an issue of The Pioneer, took exception to a San Francisco Evening Bulletin critique of the poem, "The Woman Who Dared," by Eppes Sargent. '"Free Love,' as we understand the term," Stevens wrote, "means a free and untrammeled intercourse between the sexes, and that any public sentiment or legal enactments that impose restraints on human passions, or limits their actions, are arbitrary and oppressive."(25) While she dismissed the aesthetic quality of the poem, her main intent was to take The Bulletin to task for taking parts of the poem out of context. "It is customary in literature as in law, when grave charges are preferred against an author or his book, to furnish the evidence upon which the charges are founded," she wrote.

It was Pitts Stevens's defense of free love that the public remembered, however, and as she became more deeply involved in the national suffrage campaign she was repeatedly forced to defend herself against the mainstream press's accusations that she was morally unfit. Pitts Stevens was the moderator when, at her invitation, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony spoke in San Francisco in July of 1871. While the criticism then directed at Pitts Stevens was harsh, it worsened two years later when she welcomed Anna Kimball, a champion of Victoria Woodhull and the free love movement, to San Francisco. As a result of the abuse Pitts Stevens received from both the press and some of her peers in the movement for her support of Kimball, she resigned from the CWSA. In subsequent years, while continuing to support suffrage, she devoted her prodigious energies to the temperance movement, a less politically explosive endeavor for her. By contrast, Amanda Slocum, who was less bourgeois than Pitts Stevens, consciously refrained from putting herself in public situations where she would have to defend her unorthodox beliefs.

Also in 1871, a contentious legal dispute in San Francisco, which spurred Lisle Lester and other women activists to rally, left Lester brutally beaten. Laura Fair, who was accused of murdering her married lover, was tried by a jury of twelve men. When Lester and others protested that Fair had not received a fair trial, a man wielding a cane attacked and severely injured Lester. For Slocum, Pitts Stevens, Lester, and others, these and other experiences demonstrate some of the ways activist women accommodated—or paid for opposing—Victorian morality.(26)

Publisher Dora Darmoor took exception to the more radical wing of the woman's suffrage movement, particularly to the free love, free thought philosophy promoted by Woodhull and reported in Slocum's Common Sense. Darmoor, whose Golden Dawn circulated from 1874 to 1876, wrote that she intended "to keep her paper separate and above the fray." She then attacked Slocum's ideas as nonsense.(27) Though Darmoor was genteelly committed to women getting the vote, she was not a supporter of universal suffrage. She wrote that "suffrage should be restricted to the educated ... not to sex, color, nor other natural qualification" and opposed the granting of suffrage "to the lowest class" of recent immigrants.(28) The rejection of male ethnic minorities' access to the ballot by these white, middle-class, and mostly educated women should be seen within the context of the abolition movement and the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. The granting of the vote to all men, including uneducated former slaves and functionally illiterate immigrants, provoked bitter prejudicial reactions among educated white women. None of the women in this study ever conveyed the remotest connection to or identification with other marginalized groups. In fact, most of them took great pains to separate themselves, morally and intellectually, from uneducated, working-class immigrant, men.

'Marietta Beers-Stow, shown in this lithograph portrait, was the most politically astute and successful of the San Francisco women newspaper publishers. She wrote several books addressing women's legal disabilities and was the first woman to run for vice-president, on the Equal Rights Party ticket with Belva Lockwood in 1884.

Courtesy The Bancroft Library

Like Young, Beers-Stow promoted a holistic approach to reform in her newspaper, the Woman's Herald of Industry and Social Science Cooperator, which debuted in September of 1881. Furthermore, as president of the newly formed California Woman's Social Science Association (SSA), Beers-Stow's paper was the mouthpiece for this alternative movement, whose board included only women.(29) Beers-Stow listed seven reasons for publishing the Herald, which coincided with the SSA's interests:

First, because the daily and many of the weekly papers are mainly devoted to the interest and wellbeing of the representative class. Second, to prove that the triple 'curse' (labor, childbearing, subjection), under which woman has been held for all time is false. Third, to preach the new gospel of fewer and better children. Fourth, to preach the new gospel of co-operation. Fifth, to preach the gospel for preventing crime. Sixth, to lay bare the mischief resulting from a purely masculine form of government in Church and State; and Seventh, to get the laws of inheritance amended so that widows would stand equal with widowers before the law.(30)

The SSA promoted an alternative healthful lifestyle that one hundred years later would fit without too much difficulty into today's New Wave movement. Her newspaper agitated for not only political reform but also nutritional and clothing reform. Her identification of class conflict, the need for birth control, and a cooperative alternative to capitalism places her movement well outside the mainstream. As the penniless widow of a very wealthy hardware store merchant, for years Beers-Stow unsuccessfully battled the state of California to receive a portion of his estate. Her experiences about the inequities widows faced in the legal system led her to publish two books, Probate Confiscation and Probate Chaff. In Women in Printing, Levenson noted that Beers-Stow's efforts "hastened the adoption of community property laws in California."(31)

Although Beers-Stow supported women's rights and suffrage, she differed from the other publishers in this study over the means to achieving those goals. She took a pragmatic approach to gaining both the franchise and legal equality for women, yet women's unequal legal and political position handicapped all her formidable efforts. As a result, she focused her efforts on demonstrating how much woman's subservient position in society stemmed from inequities in the law. In addition to her two books, she wrote articles on the history of woman's legal and social status, participated in writing legislation to change inheritance laws, and worked to enact laws that improved conditions for factory workers and limited the work day to eight hours. Beers-Stow served as the second president of the CWSA, and, like Shenck and Pitts Stevens, she worked at both local and national levels for woman's suffrage. In 1882 she ran for governor of California. In 1884 she was the first woman to run for vice president on the national ticket of the newly formed Equal Rights party, with Belva Lockwood as the presidential candidate.

Like her peers, Beers-Stow did not extend her goals for social equality to non-white minorities in San Francisco. Her campaign for governor included the pledge to remove the Chinese from California. In the same breath she took to espouse her philosophy of social cooperation, she attacked the Chinese presence in California. She wrote that one of the evils of child labor was that white children were forced to work side by side with "Chinamen." "If the Chinamen must be employed," she wrote, "put them by themselves."(32) Her vision of a socially cooperative utopia included whites only.

Beers-Stow also promoted clothing and food reform in her paper. She regularly presented articles espousing the benefits of alternatives to the corset and layers of clothing Victorian women were expected to wear. She promoted several costumes, but most included a pair of pants worn beneath an apron-like garment that allowed greater freedom of movement without fully shocking the mores of the time. To advance this cause, she financed competitions and awarded prizes for the best alternatives to the restrictive women's attire of the late nineteenth century. She published testimonials from women who had liberated themselves from the corset. Cornelia Boecklyn of Burlington, Iowa, for example, declared that she had "worn pantaloons for 11 years and have no desire to wear any sort of skirt."(33) Beers-Stow invented her own alternative to the corset, the Tripple S. Costume, and marketed it in her Women's Herald. By early 1885, however, she had turned her interests to lecturing and philanthropy, and ceased publication of the newspaper.(34)

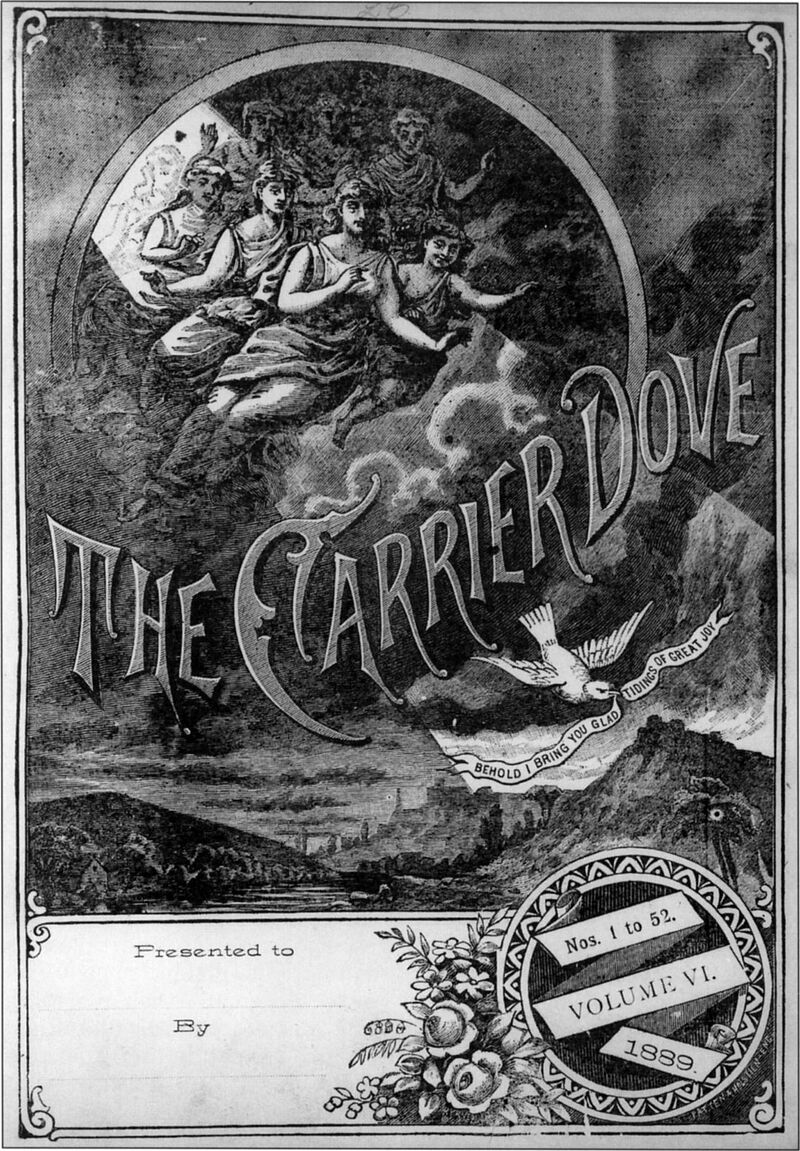

Julia Schlesinger, right, presided for ten years over the last woman-edited newspaper in San Francisco in the nineteenth century The Carrier Dove.

Courtesy California Historical Society

Founded in 1883, two years after the Women's Herald, The Carrier Dove survived for a full decade, and gained a national following. It was the last newspaper published by a woman during that century. Publisher Julia Schlesinger, like some of her predecessors, also used the WCPU to print her newspaper. The Dove’s primary focus was spiritualism, an alternative religious movement begun at mid-century. Schlesinger also filled the weekly with news of the suffrage, temperance, and woman's rights movements. Almost every issue included columns on the injustice of withholding the elective franchise from women. "Without the ballot woman is dwarfed," began one article.(35) Another, titled "Election Day from a Woman's Viewpoint," disputed "the prevailing opinion that women have no concern for the science of government."(36) The timing of The Carrier Dove, with its spiritualist focus, proved auspicious. Of the newspapers surveyed here, it enjoyed the longest run and the widest readership. Nonetheless, its demise in 1893 ended the era of women-published newspapers in San Francisco.

The weekly Carrier Dove was printed by the Women's Co-operative Printing Union. This photograph shows the engraved cover, which holds the bound edition for 1889.

Courtesy California Historical Society, North Baker Research Library, Gift of Robert S. Schwantes; FN-32464.

The conditions that had cultivated independent women's adventures during the preceding forty years had begun to disappear by 1900. In the second half of the nineteenth century, women had found it significantly easier to establish businesses in the undeveloped and labor-starved West than in the East. The impact of increased industrialization on small businesses, such as small newspapers, can be ascertained by a perusal of data in the U. S. Bureau of the Census on Manufacturing from 1860 to 1914. Before 1900, the amount of capital investment and technology necessary to establish a newspaper was relatively easily attainable for those who had access to modest capital, the willingness to work long hours, and the right skills. In the twentieth century, however, mechanized technology demanded greater amounts of capital investment, requiring newspapers and print shops to secure the support of financial groups. Marginal proposals were now typically screened out.(37)

Perhaps because they knew firsthand the precarious nature of financial independence, the women publishers in this study vigorously supported labor reforms for working women and children. At the same time, they were biased against other groups, especially Asians, and railed against the right of immigrants and black men to exercise the franchise, never recognizing their own role in perpetuating the attitudes of exclusion that others directed toward them. These and other examples of their commitment to various reforms—expressed primarily through their power of the press-helped educate the populace and thereby challenged the status quo. Yet despite their and others' prodigious efforts in support of women's suffrage, California women did not win the vote until 1911.

In the 1870s, women's political engagement expanded into broader organizational activity. Clearly a response to the exclusion of gender from the Fifteenth Amendment, women came to realize that no one was going to give them the vote. They would have to earn it. An articulation of the struggle may be found in "Woman, as a Revolutionist," an essay published by Pitts Stevens in The Pioneer. "Nothing is clearer, " she wrote in part, "than that woman must lead her own revolution. Only woman is sufficient to state women's claims and vindicate them."(38) Although women did attempt to lead this revolution, in reality they possessed few instruments of power or advantage.

Passage of women's suffrage was further thwarted by the highly masculinized party politics of the late nineteenth century. Beers-Stow, who, like others, recognized that this handicap reduced women reformers to citizens outside the electorate, reported regularly on political maneuverings that sabotaged suffrage and reform efforts.(39) With their presses as podium, Beers-Stow and others fought against the gendered nature of civic affairs. Although they had virtually no access to decision-making functions of public office, their growing political sophistication can be seen in their increasingly pragmatic and specific approaches to change.

Most of the fourteen women here believed that the vote was the key to solving the many inequities women faced. "The moment women have the ballot," wrote Pitts Stevens, "I shall think the cause is won."(40) She was indeed a political realist, but her unshakable belief also in the "march of progress" clouded her ability to fully comprehend the formidable obstacles to women's enfranchisement. While a handful of women controlled the small periodicals discussed here, the mainstream press was often hostile to or bemused by, but only occasionally supportive of, women's suffrage. The movement's success required a fundamental change in public attitudes about women and their role in society, and these publishers were instrumental in keeping alive various aspects of the discourse that, over nearly a century, finally shifted public opinion.

The fourteen women treated here were middle class, educated, of European American heritage, and all commanded printing and publishing skills. All were keen to make an impact and would defy societal pressure to conform. Yet, for all their social and political commitment, their small activist newspapers devoted little space to day-today political issues in San Francisco. A survey of the content reveals instead that they were engaged in the larger issues of the era, and sales and circulation records of these periodicals point to a readership sympathetic to their goals and content. Through the medium of the press, these publishers demonstrated their belief that American women were entitled to a public role in society. Their commitment brought essential voices to that long process.

Notes

1. The title of this article is drawn from Emily Pitts Stevens, "Our Paper and Ourselves," The Pioneer, November 13,1869, p. 1.

2. Edward C. Kemble, A History of California Newspapers (New York: Plandome Press, 1994).

3. Pacific States Newspaper Directory, 1884, p. 47.

4. The Carrier Dove appeared for a decade, from 1883-1893. See accompanying chart for a chronological list of the newspapers and women editors/publishers.

5. Roger Levenson, Women in Printing: Northern California 1857-1890 (Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1994), Appendix A, pp. 179-238. The personal and biographical information on many of these publishers is sparse, and Levenson's volume remains the best single source on their lives.

6. The last twenty years have witnessed an expanding interest in this subject. Since 1982 historians have written extensively about women's pre-suffrage role in American politics. See Paula Baker, "The Domestication of Politics: Women and American Political Society, 1780-1920," The American Historical Review, vol. 89, no. 3 (June 1981); Ava Baron, "An 'Other' Side of Gender Antagonism at Work: Men, Boys, and the Remasculinization of Printers' Work, 1830-1920" and "Gender and Labor History: Learning from the Past, Looking to the Future," in Ava Baron, ed., Work Engendered: Toward a New History of American Labor (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1991), pp. 47-69, and 1-46, respectively; Ava Baron, "Contested Terrain Revisited: Technology and Gender Definitions of Work in the Printing Industry, 1850-1920," in Barbara D. Wright, ed., Women, Work, and Technology: Transformations (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1987), 58-83; Ava Baron, "Women and the Making of the American Working Class: A Study of the Proletarianization of Printers," in Reviews of Radical Political Economics 14 (Fall 1982): 23-42; Philip J. Ethington, The Public City: The Political Construction of Urban Life in San Francisco, 1850-1900 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994); Suzanne Lebsock, "Women and American Politics, 1880-1920," Women, Politics, and Change, ed. by Louise A. Tilly and Patricia Gurin (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1990); and Elaine Tyler May, "Expanding the Past: Recent Scholarship on Women in Politics and Work," Reviews in American History 10 (December 1982): 216-33.

7. Frankie Hutton and Barbara Straus Reed, Outsiders in 19th-century Press History: Multicultural Perspectives (Bowling Green, Ky: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1995).

8. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, et al., History of Woman Suffrage, 1876-1885 vol. 3 (New York: Arno Press and the New York Times, 1969), p. 754.

9. Eleanor Flexner and Ellen Fitzpatrick, Century of Struggle: The Woman's Rights Movement in the United States (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1996), 149-56.

10. Hermione Day, 'American Women," The Hesperian, June 15,1858, p. 61.

11. Lisle Lester, "Editor's Table," The Pacific Monthly, February 1864, p. 437.

12. Ibid., 438.

13. 'A Father," "The Woman's Paper," The El Dorado, April 10, 1869, p. 1.

14. Virginia F. Russell, 'An Appeal to the Women of California, The El Dorado, April 10,1869, p. 3.

15. Emily Pitts Stevens, "The Question of the Age," February 28, 1869, p. 2, "What is Women Sphere?" March 28,1869, and "The Next Great Question of the Time," The Pioneer, April 18, 1869, p. 2. Please note: following established library cataloging, I refer to all issues of The Sunday Mercury as The Pioneer, though Pitts Stevens did not change the paper's name until November 1869.

16. Pitts Stevens, "The Next Great Question of the Time," The Pioneer, April 18,1869.

17. Masthead, The Pioneer, November 13, 1869.

18. Pitts Stevens, "Our Cause," The Pioneer, February 14, 1869, p. 2.

19. Pitts Stevens, "What is to Become of the Women?" The Pioneer, January 24, 1869, p. 2.

20. "One Effect of the Strike," San Francisco Morning Call, August 6, 1870, p. 2.

21. Carrie Fisher Young, Woman's Pacific Coast Journal, May 1870, p. 1.

22. Ibid., October 1870, p. 86.

23. "Female Compositors," Woman's Pacific Coast Journal, December 1870, p. 125; and "What Can Girls Do?" May 1871, p. 8.

24. Sandra L. Myres, Westering Women and the Frontier Experience, 1800-1915 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1982), 228.

25. Pitts Stevens, "The Bulletin and Free Love," The Pioneer', December 25, 1869, p. 1.

26. Levenson, Women in Printing, 69-70.

27. Dora Daramoor, "Let Us Have Peace," The Golden Dawn, September 1874, p. 4.

28. Daramoor, "Universal Suffrage," The Golden Dawn, December 1874, p. 5.

29. Marietta Beers-Stow, "Board of Management," Woman's Herald of Industry and Social Science Cooperator, September 1881, p. 1.

30. Beers-Stow, "Seven Reasons for Publishing the Herald," Woman's Herald of Industry and Social Science Cooperator, p. 1.

31. Levenson, Women in Printing, 152.

32. Beers-Stow, "Woes of the Female Workers in Our Midst," Woman's Herald of Industry and Social Science Cooperator, October 1881, p. 3.

33. Beers-Stow, "Dress Reform Directory," Women's Herald of Industry and Social Science Cooperator, May 1883, p. 5.

34. Levenson, Women in Printing, 157-58.

35. Julia Schlesinger, "Women's Suffrage Extracts," The Carrier Dove', November 1886, p. 279.

36. Schlesinger, "Election Day From a Woman's Point of View," The Carrier Dove', November 1886, p. 295.

37. U.S. Bureau of the Census on Manufacturing, 1860-1900, 1914, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

38. Pitts Stevens, "Woman as a Revolutionist," The Pioneer, January 31,1869, p. 2.

39. Beers-Stow, "Second President of the California Women's Suffrage Association," Woman's Herald of Industry, January 1882, p. 6.

40. Pitts Stevens, "Women Too Delicate for the Polls," The Pioneer, April 4,1869, p. 2.