A Community That Fights: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(added video) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | ''Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library'' | ||

<iframe src="http://archive.org/embed/HerbMillsAHighlySkilledJob" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | |||

'''Herb Mills on longshoring work and solidarity in the hold.''' | |||

''Video: Chris Carlsson and Steve Stallone'' | |||

Revision as of 20:57, 18 March 2013

Historical Essay

by Herb Mills

from The San Francisco Waterfront: The Social Consequences of Industrial Modernization, Part One: The Good Old Days

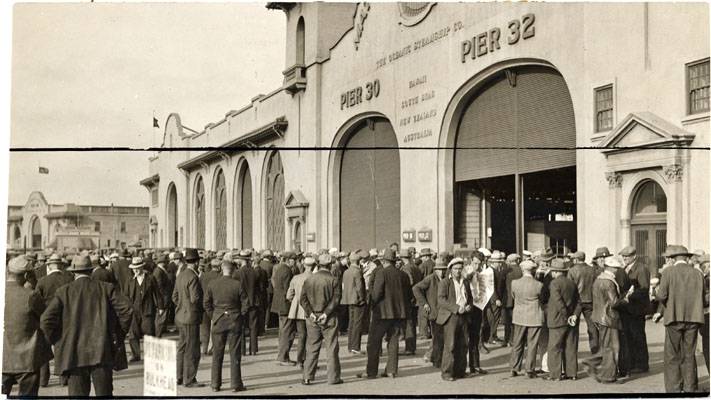

1933 stevedore strike on San Francisco waterfront.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

<iframe src="http://archive.org/embed/HerbMillsAHighlySkilledJob" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Herb Mills on longshoring work and solidarity in the hold.

Video: Chris Carlsson and Steve Stallone

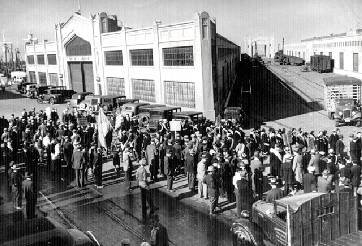

Demo against scrap metal to Japan, 1937

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

By the late 1930s, San Francisco longshoremen could walk the Embarcadero and work the docks and ships with a very considerable dignity. The most concrete expression of that dignity. . . was a quite extraordinary on-the-job militancy.

There were three distinct, yet frequently interrelated components to this militancy: (1) the enforcement of the contract, (2) an insistence upon safety, and (3) an insistence that the work proceed sensibly. Broadly speaking, an effective militancy could be exercised by the men simply because their employer was fundamentally dependent upon their initiative and good will. . . Because of the experience, skills and innovative talent which he brought to the job, the good longshoreman could routinely exercise a very effective job control when in his judgement that seemed necessary. . . The men upon whom the employer could most readily rely for a really first class stevedoring job and a very conscientious performance of the work were men who were viewed by their fellow workers as the very best of union men and the most militant of their union brothers.

File:Ilwu2$longshore-job-action-1943.jpg

Quick job-action against new "no smoking" policy, 1943.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

The ability and willingness to undertake disciplined and well-planned job action, i.e., work-stoppages or mini-strikes of limited scope and short duration, became the very hallmark of the San Francisco longshoremen. . . While the men were destined to evolve a great number of ways of collectively expressing and, therefore, experiencing their community with one another, job action was for years the mass, democratic form. It was also the most direct, immediate and vibrant. As a collective expression and experience of community, job action was a veritable fountainhead of organizational lan and individual verve. By concretely reminding the men of the nature of their struggle and of the means whereby disputes and grievances might be resolved to their satisfaction, it was also destined to play a vital role in their evolution and self-education as a community. Hence, the militancy of these men was . . . the most complete expression and embodiment of their occupational satisfaction.

Maritime workers publicly mass to discuss a strike in September 1945.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Waterfront workers in mass meeting June 6, 1946.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library