FISSURES IN GAY 'MECCA': Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m (Text replacement - "category:Gay and Lesbian" to "category:LGBTQI") |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

[[The Lesbian Bar | Prev. Document]] [[PRAYER WARRIORS | Next Document]] | [[The Lesbian Bar | Prev. Document]] [[PRAYER WARRIORS | Next Document]] | ||

[[category: | [[category:LGBTQI]] [[category:Civic Center]] [[category:1960s]] [[category:1970s]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:1990s]] [[category:Castro]] | ||

Revision as of 07:09, 16 October 2018

"I was there..."

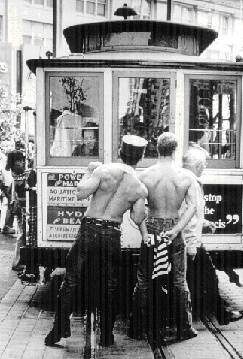

A cable car in the Castro

Photo: Crawford Barton

All was not cozy between all factions, even in the earliest days of post-Stonewall life. Leathermen were often misunderstood by their vanilla brothers. In Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation, Allen Young wrote:

"Most male homosexuals are still trapped by notions of masculinity. It is a familiar story--the oppressed worships the oppressor. Listen to the names of some of America's gay men's bars--The Stud, The Tool Box, The Barn. What passes for gay men's art--including murals in these bars--often depicts such masculine characters as the Body-Builder, the Motorcyclist, the Cowboy. What goes on inside most of these gay bars often preserves the notion that the people inside are "real men," too. The billiard table, the sawdust on the floor, the leather vest on the bartender, and, most of all, the men standing around with carefully groomed indifference while quaffing their beer . The gay man's quest for masculinity, or exaggerated masculinity, cannot be dismissed as mere evidence of his sexism. Beyond that, it is evidence of oppression, evidence of how a minority is overwhelmed by the values and style of the majority.

"While fully recognizing the oppressive nature of dimly-lit bars in out-of-the way streets such as Folsom Street in San Francisco, we will continue to preserve the bars as temporary gay turf where there is at least minimal freedom for gay people."

There was a great deal of fear about the gay leathermen amongst their vanilla brethren. During the late '60s and early '70s, when many gay men and women were coming out, they were just learning to feel good about their own sexuality. To introduce forms of sexual behavior seen as even more bizarre and risky was doubling the burden. So even where there was curiosity about the S/M world, many gays suppressed it.

KIM STORCH: People were scared. I mean, I wouldn't go out with anybody with a black leather jacket for the first three or four years I was in San Francisco, because I was afraid of what it might mean. I didn't know what it did mean, until I saw that there was negotiation possible. The whole territory was off-limits because it scared me.

BILL BRENT: I agree. I had the same experience, much later.

KIM: Once I saw that you could negotiate from vanilla, all the way through that I could have my friends watch, the first time I got tied up, and the second, and the fifth, and then, I liked having them watch -- you could develop interrelatedness to the other people who were at those parties frequently.

MARK THOMPSON: I think there's always been kind of an uneasy alliance. The leathermen and the drag queens were both marginalized, even though they were opposite ends of the spectrum . You know, "Those nasty sadists -- that's not us. We're the nice gays. Those are the bad gays." So there was that element, even though I think a lot of them were hypocrites. Of course, they'd say that during the week, and then on Saturday night, they'd be with their feet up in the air, in a sling at the Slot or some place like that, hoping no one would notice.

--Bill Brent, Black Sheets magazine, from which this material was excerpted.