Postwar Sex District: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (Text replacement - "category:Gay and Lesbian" to "category:LGBTQI") |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

Times again changed, and today there are at least 10 strip clubs drawing thousands of tourists. The nightlife is once again thriving, offering all sorts of adult entertainment: nightclubs, tours of North Beach Gentlemen’s Clubs, peep shows, massage parlors, and escort services of all sorts. The sex industry has taken on a life of its own, establishing itself as an integral part of the landscape and contributing so significantly to the economy of San Francisco that no one wants to disturb it, for now. | Times again changed, and today there are at least 10 strip clubs drawing thousands of tourists. The nightlife is once again thriving, offering all sorts of adult entertainment: nightclubs, tours of North Beach Gentlemen’s Clubs, peep shows, massage parlors, and escort services of all sorts. The sex industry has taken on a life of its own, establishing itself as an integral part of the landscape and contributing so significantly to the economy of San Francisco that no one wants to disturb it, for now. | ||

[[category:1900s]][[category:1910s]][[category:1930s]][[category:1940s]][[category:1950s]][[category:1960s]][[category:1970s]][[category:1980s]][[category:1990s]][[category:Gold Rush]][[category:North Beach]][[category:Dance]][[category: | [[category:1900s]][[category:1910s]][[category:1930s]][[category:1940s]][[category:1950s]][[category:1960s]][[category:1970s]][[category:1980s]][[category:1990s]][[category:Gold Rush]][[category:North Beach]][[category:Dance]][[category:LGBTQI]][[category:Bayview/Hunter's Point]][[category:Tourism]][[category:Mayors]][[category:Gentrification]] | ||

Latest revision as of 07:09, 16 October 2018

Historical Essay

By Libby Ingalls

Adapted from "Excavating the Postwar Sex District in San Francisco," by Josh Sides, Journal of Urban History 2006; 35; 355

Commercial sexual entertainment and prostitution have been a fact of life in San Francisco since the first days of the Gold Rush. As the city grew and evolved over the decades, sex for sale has reinvented itself, adapting to changes in attitudes toward sex, legal criteria of obscenity, urban development, and city politics. What began as a bawdy district anchored by brothels appealing to transitory miners, evolved into a more fluid, integral part of San Francisco, ultimately leading to a new phenomenon with the sexual revolution of the 60s and the immense profitability of the sex industry.

The proper place of sex in the city has been debated since 1849. In those early days, the Barbary Coast district housed most of the brothels, with prostitution being the main business. The district also offered other forms of sexual entertainment, including crude burlesque, belly dancing and other sexually explicit dance forms, saloons with half-clad waitresses, and peep shows.

Barbary Coast "Ladies" in 1890.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

The various crusades against sexual entertainment, usually by Christian groups, made little progress when sexual permissiveness and political corruption prevailed. Attempts to crack down on prostitution just caused it to move to another street or neighborhood. The status quo was further maintained by protection money, often paid to police officers, and at least one mayor, Eugene Schmitz (in office 1902-07).

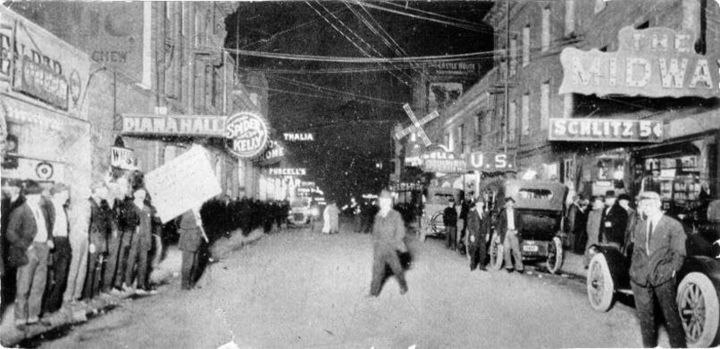

Crowds on Pacific Avenue during height of Barbary Coast in 1913.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

This was all to change in 1911 with the defeat of the Union Labor Party, and public sentiment turning against San Francisco as a “wide-open town.” At the same time, the city was about to host the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915, and the business elite, who had collectively pledged $4 million toward the Expo, feared the notoriety of the Barbary Coast would discourage visitors. They pressured Mayor James Rolph, who personally tolerated prostitution, to effectively shut down the Barbary Coast. Rolph’s new policies outlawed prostitution, dancing in any saloon, the presence of females in saloons, and the issuance of any new licenses for saloons. Newspaper magnate and owner of the SF Examiner, William Randolph Hearst supported the mayor with a series of articles on the evils of the Barbary Coast, encouraging the mayor to replace it with “decent fun.” The new police commissioner, James B. Cook, jumped on the bandwagon with his own campaign to close down the sex district. Then in 1914 the California voters approved the Red-Light Abatement Law, fining property owners where prostitution was taking place, sealing the fate of the Barbary Coast, for the moment anyway.

As is the nature of prostitution, it doesn’t just go away, it moves on; in this case, to the Tenderloin. The migration of the prostitutes coincided with the shift in the neighborhood’s chief theatrical entertainment, burlesque, from witty, satirical, imaginative performances to exposure of the female body.

Sally Rand, the infamous strip tease artist of the 1930s, performed at the San Francisco International Exposition of 1939, then opened a regular stint at the Music Box on O’Farrell. Local imitators followed, and soon burlesque and strip tease performances were supporting a thriving neighborhood commercial sexual economy.

It wasn’t long before North Beach got in on the action and revived its own thriving nightlife. Three main influences brought this about: the Repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island, and the opening of the gay nightclubs, Finocchio’s and Mona’s. This time, however, nightclubs were more timid, advertising themselves as “theatre restaurants” with sophisticated floorshows and musical entertainment. Property owners wanting to increase real estate values emphasized this new respectability and international appeal. Seeking a connection with the 1939 Exposition, they built an archway on Pacific and Kearny reading “International Settlement” announcing their intended transformation of the Barbary Coast. Promoting respectability by property owners, however, could not stop the opening of new clubs, commercial sexual entertainment, and the resurfacing of San Francisco’s reputation as a wide-open town. A new dimension was the growing gay population, fueled by the administrative role of San Francisco in World War II as the point of disembarkation for gay men dishonorably discharged from service in the Pacific.

But by the mid-1950s, commercial sexual entertainment again came under attack, this time by ideologically driven proponents of McCarthyism. Their charge: sexual perversion could lead to communist sympathy. In the name of national security and patriotism, prostitution was once again targeted. Republican George Christopher won a landslide victory in 1955 on an anti-vice, pro-business platform, and thus continued a well-orchestrated campaign of the 1950s to wipe out public and commercial sexuality from North Beach. As part of the cleanup, Pacific Avenue, the former heart of the Barbary Coast, was transformed into a wholesale interior decorating supplier district, Jackson Square.

Try though political and business interests might to control North Beach, the free and independent spirit was irrepressible. In the mid to late 1950s, North Beach attracted an influx of writers, poets, artists, and free thinkers with the cheap apartments and numerous cafés and bars. The most notorious Beats, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William Burroughs, stayed only briefly in North Beach, leaving by 1956, but their legacy continued on in the aura, imagination and landscape of North Beach. Nightlife thrived once again.

A defining moment came in June 1964, when Carol Doda performed her topless swim dance at the Condor. Dozens of similar acts followed, attracting thousands of tourists, servicemen, conventioneers, and locals, matched only by the original Barbary Coast before 1913. Out on the streets, pedestrians could peer through picture windows and view topless dancers.

Religious leaders were up in arms, joined by “legitimate” nightclub owners fearing the competition, and the North Beach merchants arguing that the weekend congestion hurt business. Added to this was the controversy over the question: was topless dancing obscene, and, therefore, illegal? Mayor Jack Shelley, the first Democratically elected mayor in 50 years (elected in 1963), ordered a raid to bring the issue to court. Two judges acquitted the dancers and owners of the topless nightclubs, paving the way for the spread of topless and bottomless entertainment. Massage parlors, as fronts for prostitution, were not far behind, followed by a proliferation of pornographic bookstores and pornographic movie houses. In 1966 the city populace rejected Prop 16, a ballot initiative that sought to tighten obscenity laws. The sexual revolution was in full swing. For gays and straights alike, unfettered sexual expression was seen as a right rather than a frivolity. By 1970 there were 47 hardcore pornographic bookstores and 28 pornographic movie houses, in North Beach, the Tenderloin, Polk Street and South of Market, along with dozens of peep shows and strip clubs.

With obscenity laws crumbling, the sexual revolution on the rise, and public opinion supporting civil liberties, post-war sex districts became a feature of America’s large cities. Enter Hollywood. Here was rich fodder for the gritty films of the 1970s. Narcotics had infiltrated sex districts, but nothing like the seediness Hollywood invented, featuring hustlers, murderers, pimps, and prostitutes. Granted there were arrests for petty theft and prostitution in North Beach, but the highest rate of violent crime remained in other neighborhoods. Nevertheless, inflamed by films, the specter of violence persisted. The city once again took action, this time with Dianne Feinstein leading the charge.

Dianne Feinstein was elected to the Board of Supervisors in 1969, becoming president in 1970-71, 1974-75, and 1978. Her campaign against the sex district started with an ordinance to remove signs, followed by an attempt to prohibit sex businesses from operating within 1,000 feet of another. Downtown business elite concerned with business and real estate values strongly supported Feinstein, who herself had personal ties to downtown development. Opposition to Feinstein came from Harvey Milk, the ACLU, and mothers of Bayview Hunter's Point, as the zoning stipulations left Bayview Hunter's Point as the most obvious place for the sex businesses to move, with its warehouses and open spaces.

The Board of Supervisors rejected the zoning ordinance, but Feinstein continued to fight for controls of pornography and reduction of commercial sexual entertainment. The controls did come about, but ironically Feinstein had very little to do with it.

Outside factors were far more effective than Feinstein’s efforts. First, there was the introduction of the VCR that allowed potential customers to stay home for their entertainment. Secondly, the AIDS epidemic led to the closing of gay bathhouses, sex clubs and other venues of sexual activity. And third, the rapid rise in the value of downtown commercial real estate brought an influx of young, affluent residents seeking food and entertainment in North Beach, and property values there began to soar. The old haunts of North Beach were getting priced out of the market. By the early 1990s only four of the original 28 strip clubs of North Beach remained.

Times again changed, and today there are at least 10 strip clubs drawing thousands of tourists. The nightlife is once again thriving, offering all sorts of adult entertainment: nightclubs, tours of North Beach Gentlemen’s Clubs, peep shows, massage parlors, and escort services of all sorts. The sex industry has taken on a life of its own, establishing itself as an integral part of the landscape and contributing so significantly to the economy of San Francisco that no one wants to disturb it, for now.