Displacement and Trauma: A Public Health Crisis: Difference between revisions

m (Protected "Displacement and Trauma: A Public Health Crisis" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite))) |

(fixed categories) |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

[[category:roads]] [[category:downtown]] [[category:Tenderloin]] [[category:Civic Center]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:1990s]] [[category:2000s]] [[category:2010s]] [[category:Real | [[category:roads]] [[category:downtown]] [[category:Tenderloin]] [[category:Civic Center]] [[category:1980s]] [[category:1990s]] [[category:2000s]] [[category:2010s]] [[category:Real estate]] [[category:Public Health]] [[category:Homeless]] | ||

Revision as of 17:14, 21 March 2020

Historical Essay

by Erick Lyle

In February 2016 a burgeoning community of homeless was camped along Division Street under the freeway. Activists had acquired and provided tents to many.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The true extent of the enormous loss of life, culture, and community suffered in cities like San Francisco and New York during the height of the AIDS epidemic – famously ignored by those in power at the time — has at last, due to the tireless efforts of those who lived through that era, begun to achieve some small, hesitant measure of acknowledgement in mainstream histories. Similarly, while those affected by displacement have struggled in the face of media and government silence to make known the widespread health and social effects of gentrification on displaced communities, it remains to be seen if the losses suffered during the past three decades’ era of unrelenting gentrification will ever be recognized in the official histories of our era.

Meanwhile, we have only some statistics that hint at what has been lost during the past several decades when the great erasures of the AIDS crisis and the gentrification eras merged. San Francisco’s African American population has decreased by 35% in the past two decades. The Latino population of the Mission District has fallen 20% in the same time. Since the beginning of the epidemic, approximately 20,000 people have died of AIDS in San Francisco. Another 10,000 people in the city are currently living with the disease.

In the same span of time, the cultural landscape of San Francisco has been utterly transformed. A once-vast network of arts and activist community spaces, collectively-owned businesses, bookstores, working class restaurants and bars, queer spaces, music venues – many of which had been thriving for decades – have closed their doors due to rising rents. Due to government budget cuts, welfare has been slashed, public housing has been decommissioned, and neighborhood health clinics have been closed.

A day laborer without shelter catches some shut-eye in front of a basement door, 2015.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

I want to be clear that I do not in any way intend to suggest that different displaced communities have all experienced the violence of gentrification in the same way. Nor do I wish to equate, compare, or conflate the losses suffered by distinct communities. I group them together here because it is in the ghostly outline of their shared absence from the city that we can see the true size and scope of the decades-long effort by white-supremacist corporate capitalism to remake the city in its image. I want to argue in this essay that we must abandon popular understandings of gentrification in favor of a theory of radical displacement that takes into account how seemingly disparate policies such as deindustrialization, redlining, health and welfare budget cuts and privatization of formerly public commons, are deployed in tandem alongside real estate speculation, landlord arson, police brutality, and anti-homeless legislation as part of a long term strategy to consolidate corporate hegemony.

I’d like to consider here some ways that filling in the gaps of traumatic historical narratives can help displaced communities find acknowledgement of their losses, so that they can begin to heal. I’d also like to consider ways that an embrace of the utopian can help us illuminate potential paths toward a future that is neither an impossible return to a problematic past nor simply a continuation of an unacceptable present.

Trauma

Trauma is often understood to be a body’s response to an extraordinary event that one cannot easily assimilate into their story and experience of life. Many victims of displacement experience gentrification first as this kind of problem of narrative. After all, dominant ideology tells working class people in the United States that if they work hard and play by the rules they will be rewarded with decent wages, a home, and an opportunity to educate their children. Instead, as victims of displacement find that the banks have disinvested in their communities, the budgets for schools have been slashed, their jobs have been shipped overseas, and landlords benefit from illegal evictions, they begin to understand the game has been rigged. Yet in a society where increasingly only the needs of the market are met, those who fall victim to displacement are told their failure is all their own and not part of any greater social ecology.

Indeed, while displacement has been shown to have a tangible negative impact on community health, there has been little effort in government or academic circles to examine or understand the psychological and health effects of the slow-motion disappearances of communities deliberately displaced by government policies. There are some new statistics, however, that hint at how these erasures might be experienced by some. In a recent study of displaced communities in Oakland, The Center for Disease Control concluded that low-income “populations [vulnerable to and experiencing gentrification] typically have shorter life expectancy, higher cancer rates, more birth defects, greater infant mortality, and higher incidence of asthma, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.”

Communities affected by displacement are also more at risk to endemic violence – often at the hands of the police. The African American population now comprises just 6% of the San Francisco’s total population, and the Latino population has fallen to 15% of the population. Yet, together, African Americans and Latinos accounts for 75% of all arrests by police officers in the city. While overall murder and violent crime rates have fallen to historic lows in the city, the murder rate among youth of color has skyrocketed, as teen gang members gun each other down in front of expensive restaurants and $5000 a month apartments. The leading cause of death for people under the age of twenty-four in San Francisco is now homicide.

In gentrifying neighborhoods in cities across the country, local law enforcement have used crime rates as a pretext for introducing the tactic of court-ordered gang injunctions, which strictly monitor the activities of youth of color. Critics of gang injunctions in cities like Los Angeles and Oakland have pointed out that gang injunctions, which greatly curtail the freedom of movement of youth of color, are often imposed on neighborhoods slated for imminent gentrification as a way to clear the streets for new white residents. Indeed, the city’s attorney office in San Francisco has applied gang injunctions in the gentrifying Western Addition, Bayview, and the Mission District, where twenty-nine men believed to be members of the Norteno gang are strictly forbidden from congregating together within a sixty square block “safety zone”. Subject to a ten p.m. curfew, the men cannot so much as publicly walk or talk with others covered by the injunction, including members of their own family. Those affected by gang injunctions often face deportation or prosecution under Federal racketeering charges. Critics claim that the injunctions make the job of teen outreach workers more difficult while doing nothing to address the root poverty and lack of economic opportunity that bolster gang membership. No one can say for sure whether the constant police presence and the stressors of gentrification are directly responsible for the escalation in youth violence. But gang violence continues unabated in gentrifying neighborhoods.

Tech bus turns onto 24th Street as debris from nearby fire that displaced dozens fills the street, April 2016.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

In the collision between the newly gentrified Mission District and the old neighborhood’s intractable poverty, we see another tale of competing San Francisco realities. Many top Zagat and Michelin rated restaurants have opened in the Mission in recent years, and the area enjoys a reputation as the hippest dining area in the city. After a series of spectacular gang shootings in proximity to trendy Mission restaurants in 2011, the news site Mission Local published a map of the neighborhood called “Gangs and Cupcakes,” which overlaid a map of the neighborhood’s gang territories with a map of its new artisan bakeries. While the affluent and largely white patrons who frequent these establishments enjoy an era that is statistically for them the safest in decades, the restaurants’ Latino kitchen workers face real danger every day. In 2011, a Latino line cook at popular eatery Hogs & Rocks was outside of the restaurant smoking a cigarette when he was approached by gang members who asked him what gang he belonged to. When he said he belonged to none, he was shot in the face and killed.

Despite this high profile violence, there has been no public health research on how gentrification directly affects gang violence. While social epidemiologists have done much work to consider the effects of displacement on war refugees or the effects of slum clearance on its inhabitants in other countries, the effects of displacement upon affected communities in urban centers in the United States has largely been ignored or disavowed by those with the power to investigate.

In fact, those most responsible for the displacement work hard to hide their actions and naturalize the violence that they help inculcate. The narrative structure that developers, city planners, realtors and landlords use to talk about gentrification is incredibly similar to the denial tactics of abusers, and perpetrators’ narratives are very similar in instances of traumatic abuse and in gentrification. Each refuses their victims acknowledgement of their pain and instead obscures their own responsibility by coercing victims into accepting as truth a false and sinister dialectic: It never happened, but you deserved it. What a trauma sufferer often most wants is acknowledgement by the perpetrator that an injury was done and that it was wrong. But the planners of gentrification will do everything in their power to deny any responsibility for its effects.

On the one hand, the architects of gentrification obscure the years of planning, government contracts, re-zoning and policy manipulation that go behind every “up-and-coming” neighborhood -- to say nothing of the police brutality, landlord intimidation, arson, and other forms of violence that are the true shock troops of gentrification-- by pretending gentrification is a kind of “natural” phenomena, like a weather pattern, that inevitably occurs whenever rich people move into a poor neighborhood (It never happened). On the other hand, if pressed they might say something like, “OK, maybe stop and frisk is a little invasive. But, hey, everyone knows it used to be worse back then with all the winos and muggers and gangs and junkies and homeless people and, besides, these beautiful old brownstones were just falling apart from neglect until we came along and fixed them up. (You deserved it).”

In recent years, San Francisco tenant organizations have made some inroads in their public struggle for acknowledgement of the public health effects of displacement. In 2004, a developer announced intentions to raze the Trinity Plaza apartments on Market Street and to build in its place five residential towers of condominiums. The plan would result in the loss of 377 rent-controlled apartment units, to be replaced with 1410 new units—almost all to be leased at market rate. Tenants organizations fought the development and in the process, persuaded the San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) to conduct an Environmental Impact Review (EIR) that took into consideration the effects on the health of the Trinity Plaza residents and those in the surrounding area that would be impacted by the enormous development.

Trinity Plaza replacement towers, July 2013. A third tower is nearing completion in 2017.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

SFDPH epidemiologists interviewed Trinity Plaza residents, asking them “What about where you live right now makes you healthy, and what about the threat of eviction affects your health?" SFDPH concluded that,

“Lack of affordable housing can lead to malnutrition, poor health care, and even homelessness. In addition to housing affordability, inadequate housing can have adverse effects on public health. Redevelopment, renovations, or conversions of residential property can result in increased rents, displacement, and even homelessness. These effects can have indirect adverse effects on human health by causing poverty, loss of social support, and substandard living arrangements.”

The findings of the SFDPH study gave tenants organizations and sympathetic members of the Board of Supervisors more ammunition to demand that the new development include more affordable housing. Facing cost overruns from delays, the developer ultimately gave in and agreed to provide all Trinity Plaza residents with rent-controlled units at their current rate in the new development.

While this use of public health concerns in an Environmental Impact Review is the first such successful attempt in the city to use research about the negative effects of development on public health to curtail development, results in San Francisco have thus far still been mixed. In opposition to a proposed 2005 development at Rincon Hill, SFDPH again testified in public hearings that the development would have a negative overall impact on the public health of the city. The Planning Commission chose not to follow SFDPH recommendations and approved the development anyway.

While the emerging understanding of displacement as a public health concern has given tenant activists a new organizing tool against developers, the fight for greater understanding and recognition of the realities of displacement is also an important part of healing from community trauma. People who have survived or witnessed traumatic events have a profound need to develop what therapists call “trauma narratives” to help make sense of their experience. Talking about a traumatic experience helps organize troubling memories and make inchoate feelings more manageable and is a significant step in the trauma recovery process.

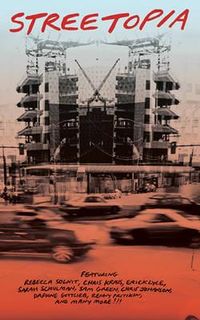

Excerpted from Streetopia, in the essay "The Uses of Market Street"

See other parts of this essay: