WAITRESSES and UNIONS The Fruits of Solidarity: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

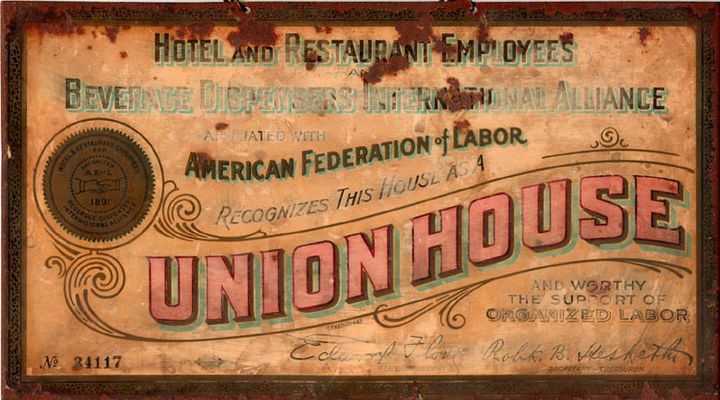

In the early 1930s, Local 48 confronted unrelenting employer pressure for wage reductions and lowered standards. Delighted by the meager standards set by the NRA codes, restauranteurs replaced their union house cards with the Blue Eagle insignia (indicating compliance with government recommendations), lowered wages, and reverted to the fifty-four-hour week."42 | In the early 1930s, Local 48 confronted unrelenting employer pressure for wage reductions and lowered standards. Delighted by the meager standards set by the NRA codes, restauranteurs replaced their union house cards with the Blue Eagle insignia (indicating compliance with government recommendations), lowered wages, and reverted to the fifty-four-hour week."42 | ||

[[Image:Waitress Union Local 48 hq 440 Ellis AAD-5704.jpg]] | [[Image:Waitress Union Local 48 hq 440 Ellis AAD-5704.jpg|600px]] | ||

'''Local 48 headquarters, 440 Ellis Street.''' | '''Local 48 headquarters, 440 Ellis Street.''' | ||

Revision as of 19:24, 1 June 2020

Historical Essay

by Dorothy Sue Cobble

Waitresses from Local 48 in 1925 Labor Day Parade in San Francisco.

Photo: Labor Archives and Research Center at J. Paul Leonard Library, SF State

In San Francisco, waitresses enjoyed not only a long tradition of separate-sex organizing among workers and city residents, but also a solid union consciousness that resurfaced with a vengeance in the 1930s. Waitresses' Local 48 organized first in restaurants patronized by union clientele, spread its drives to restaurants outside working-class neighborhoods, swept up cafeteria, drugstore, and tea-room waitresses, and then embraced waitresses employed in the large downtown hotels and department stores. By 1941, waitresses in San Francisco had achieved almost complete organization of their trade, and Local 48 became the largest waitress local in the country. Their success resulted from a combination of factors: an exceptionally powerful local labor movement; sympathetic, fair-minded male co-workers within the Local Joint Executive Board (LJEB); and the existence of a waitress organization committed first and foremost to organizing and representing female servers.

In the early 1930s, Local 48 confronted unrelenting employer pressure for wage reductions and lowered standards. Delighted by the meager standards set by the NRA codes, restauranteurs replaced their union house cards with the Blue Eagle insignia (indicating compliance with government recommendations), lowered wages, and reverted to the fifty-four-hour week."42

Local 48 headquarters, 440 Ellis Street.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Former Local 48 headquarters building, now a landmark, as seen in early 2018.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

In response, Local 48 informed the owners that the five-day, forty-hour week was the union standard, and, in conjunction with the other culinary crafts, they picketed some 284 restaurants in 1933 alone. They side-stepped restrictive local picketing ordinances by "selling" labor newspapers in front of targeted eating establishments during peak business hours. The attorney for one distraught employer complained to the judge that "the women walked back and forth in front of the plaintiff's restaurant, and prominently displayed newspapers bearing the headline in large black letters 'Organized Labor' and 'Labor Clarion,' and each of said women called out repeatedly in a loud, shrill, penetrating voice, at the rate of 30 to 40 times a minute, 'organized labor' 'organized labor.'"(43)

Culinary workers also resisted wage cuts in the hotels. After two years of reductions totaling 20 percent, the cooks struck the leading hotels in April 1934. The San Francisco LJEB considered calling a general strike of all culinary workers in San Francisco, but Edward Flore, assisted by federal mediators, convinced employers to submit the cooks' dispute to an arbitration board.(44)

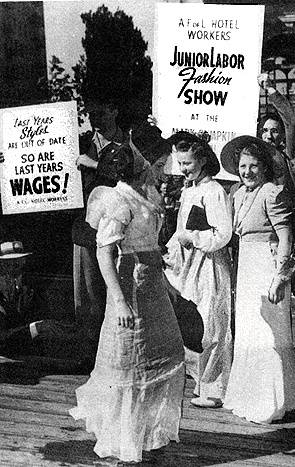

Costume picket line of hotel workers in early 1940s.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco, CA

Less than two months after the first discussion of an industry-wide strike, culinary union members voted 1,991 to 52 to join the emerging citywide shutdown on behalf of striking maritime workers. Outraged over the death of two workers--one of whom was a cook and member of Local 44--during a bloody clash between police and picketers who had gathered in support of striking longshoremen, the San Francisco labor movement brought business to a standstill for three days. In the end, they secured collective bargaining in the maritime industry. The solidarity and militancy displayed by the culinary locals was typical. The International union wired sanction for an industry-wide sympathy strike, and culinary crews walked out 100 percent at midnight on Sunday, July 15. The few houses that dared open the following Monday morning closed their doors after "a little persuasion." Only two restaurants on Third Street "here strikers ate--operated by people "apparently very close to the labor movement" -- were in operation. -- Relying on the labor unity that prevailed among San Francisco unions in the aftermath of the 1934 General Strike, the waitresses' local doubled its membership over the next four years. They received general assistance from the Teamsters, the needle-trades workers pressured the kosher bars into compliance, and the printers, streetcar men, longshoremen, and maritime trades organized the restaurants and bars adjacent to their work sites.

Culinary spokespeople acknowledged their dependence: "There is a much better spirit of cooperation than formerly and the Culinary Workers have profited from it. We are indebted to the Maritime Unions and . . . in fact all the unions pull with us whenever we go to them with our troubles, thus our brothers did not give their lives for nothing."(46)

During the heady days of 1936 and 1937, organizing reached a fever pitch stimulated by the successful sit-down strikes in auto and other industries and the Supreme Court's favorable ruling on the constitutionality of the Wagner Act. San Francisco waitresses moved from their base in small independent restaurants to tackle campaigns in drugstore and 5 and to cent store lunch counters; in cafeterias and self-service chains; and in department store restaurants and the dining rooms of the major San Francisco hotels. The most significant breakthrough came as a result of the San Francisco hotel strike of 1937. The strike, which brought union recognition and a written contract covering workers in fifty-five hotels, inaugurated a new chapter in culinary unionism in San Francisco. With the backing of the San Francisco Labor Council (SFLC) and the promise from such pivotal unions as the butchers, bakers, teamsters, musicians, and stationary engineers not to cross the lines, three thousand hotel employees, one-third of whom were women, walked out on May 1, shutting down fifteen San Francisco hotels simultaneously.(47)

From the outset, the strikers were exceptionally well organized. "The union moved with military precision," wrote the federal mediator, "set up their strike headquarters [and] organized their picket squads, each squad consisting of one representative of each of the unions involved." As workers came off the job, they were handed printed cards bearing strike and picket instructions. Picket duty lasted for four continuous hours; failure to picket meant loss of one's job once the strike was settled. Margaret Werth, the waitress business agent assigned to the hotels, organized militant waitress picket lines and achieved notable results with her waitress parade and beauty contest. After eighty-nine days of effective mass picketing that closed off the hotels to food delivery and arriving guests, a back-to-work settlement was signed involving fifty-five San Francisco hotels. The unions gained wage increases of 20 percent for most employees, equal pay for waiters and waitresses, preferential hiring with maintenance of membership, the eight-hour day, and union work rules for all crafts. For a generation of food service workers, the curtain rang down on the open-shop era with resounding finality.(48)

After this victory, the union soon reached a separate four-year agreement with the majority of small hotels in the city. Next they secured recognition from the Owl Drug Company chain, operating eleven stores in San Francisco with culinary departments; the major resident clubs of San Francisco; the Clinton's Cafeteria chain; and, after fourteen years on the union's unfair list, the Foster System, which consisted of thirty-two luncheon restaurants. "Please rush fifty house cards," Hugo Emst, president of the San Francisco LJEB, wrote the International in 1937. "All Foster new houses will open up with a display of the house cards and other places too ... demand the cards."

The unionization of San Francisco's large downtown department stores also meant new members for Local 48. In October 1934, the LIEB moved into action against the Woolworth and Kress's 5 and 10 cent stores, placing them on the "We Don't Patronize" list, picketing, and distributing thousands of handbills house-to-house in working-class districts "to acquaint workers with the slave conditions that prevail." The Retail Clerk officials warned the LJEB that "it costs too much money to organize these national chains" and that they "would not consider wasting money on them," but the culinary workers continued picketing."(50)

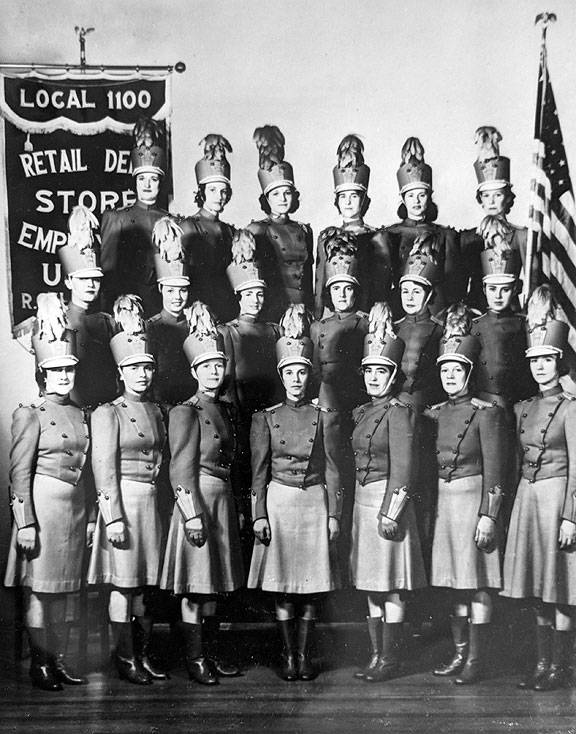

Victory came in the spring of 1937 when Woolworth and twenty-five other department and specialty stores signed on with the newly chartered Department Store Employees, Local 1100, Retail Clerks International Union, AFL. Initially, the retail local represented the food service workers in the stores as well as the sales employees because Ernst, supporting an industrial approach to organizing, had waived jurisdiction over the lunchroom employees. In 1940, however, Local 48 successfully demanded that the food service workers in department stores be part of their union."(52)

Local 1100 Drum Majorettes.

Photo: Labor Archives and Research Center, SFSU

The infant department store and hotel unions faced major trials in their first few years such as the department store strike of 1938 and the hotel strike of 1941, but unionization had come to stay. Every eating establishment of any consequence had a union agreement. The Retail Creamery Association, composed of fifty ice cream and fountain stores, signed on with the waitresses in 1940, granting a wage scale and working on a par with the waiters. A year later, the union negotiated an agreement with the Tea Room Guild (some twenty employers), winning the closed shop, a forty-hour, five-day week vacations with pay, and employer responsibility for providing and laundering uniforms.(53) By 1941, culinary union membership in San Francisco approached eighteen thousand. A majority of the hotels and motels were operating as union houses, and 95 percent of the estimated 2,500 restaurants in San Francisco were organized.(54)

Tactics: Reason, Humor, and Muscle

The organizing and bargaining tactics employed by San Francisco culinary unionists from the late 1930s to the 1950s represent the apogee of union power and creativity. With the majority of the industry union, many shop owners now voluntarily recognized the union. In 1941 alone, seventy-three restaurant owners sent the LJEB requests for union cards. Evidently, many employers judged thehouse or bar card announcing their union status essential to a steady flow of customers in union-conscious San Francisco. To promote patronage in unionized eateries, the culinary unions fined members for eating in nonunion restaurants and bought "a steady ad in the [San Francisco] Chronicle advertising the various union labels." They also appointed a committee specifically to devise "ways and means to advertise our Union House Card."(55)

In some cases, unionization appealed to employers who desired stability in an industry characterized by extreme open entry and a high rate of business failures. Citywide equalization Of wage rates protected establishments from cut-throat competitors and chain restaurants that could slash wages and prices in one location until the independent competition capitulated. Employers recognized this function of culinary unionism and on more than one occasion approached the LJEB with names of nonunion houses that should be organized. "We, the undersigned, respectfully request your assistance" began one employer plea to the LIEB. "Attempts have been made to get [unfair] places to join us . . . these attempts have failed completely. We understand that union houses are protected against cut-throats and we wonder why we have been neglected."

Union House Card, 1930s.

Photo: Labor Archives and Research Center at J. Paul Leonard Library, SF State

Culinary unionists also realized that thorough organization was necessary to protect the competitive position of Union houses. In the union campaign to organize tea roams, for example, all but a few had signed up by the summer of 1939. The union pursued those recalcitrants, insisting they were "unfair competition for the others." Reasoning along similar lines, the LJEB refused to issue house cards to employee-owned, cooperative enterprises although they met wage scales and working conditions. Their lower prices, the LJEB pointed out, were "a menace" to the union restaurants of the city. From 1937 through the 1950s, when organization among San Francisco restaurants remained close to 100 percent, many employers willingly complied with this system of union-sponsored industry stabilization and cooperation."(57)

When necessary, culinary unionists turned to picketing, creative harassment of shop owners and their clientele, and innovative strike tactics. Traditional strikes, whether by skilled or semiskilled culinary workers, rarely had much impact on businesses that could use family members or find at least one or two temporary replacements. In response, locals often picketed without pulling the crew inside. In these cases, picketing could be successful even if the potential union members working inside were indifferent or hostile to unionism. If picketing persuaded customers to bypass the struck restaurant or halted delivery of supplies, the employer usually relented. With the unity prevailing among San Francisco labor following the 1934 General Strike, culinary unionists experienced few problems stopping deliveries. Influencing customers was a far more difficult proposition.(58, 59)

Other attention-grabbing devices used by the same strikers in 1938 and again in 1941 included "Don't-Gum-up-the-Works gum" given out up and down Market Street, boats cruising the Bay during the Columbus Day celebration to advise "Do Not Patronize," and costumed picket lines. The costume variations were endless: Halloween pickets, women on skates, and even Kiddie Day picket lines. One picketer engaged a horse and buggy and trotted around San Francisco carrying a large placard that read "this vehicle is from the same era as the Emporium's labor policy." During the 1941 department store strike when a prize was offered for the picketer with the best costume, a young lunch counter striker won with a dress covered entirely with spoons; on her back she carried a sign reading "Local 1100 can dish it out but can the Emporium take it!" The 1938 dime store strikers called themselves "the million dollar babies from the 5 & 10 cent stores." Carmen Lucia, an organizer for the Cap makers International Union who assisted the strikes, recalled, "I had them dressed up in white bathing suits, beautiful, with red ribbons around them, and [they'd] bring their babies on their shoulders." Strikers' children handed out leaflets reading "Take our mothers off the streets. Little Children Like to Eat."(60)

A community contingent reinforced the continuous flow of propaganda from the strikers. One group, developed out of the 1938 strike, called itself the Women's Trade Union Committee. Open to union women and wives of union men, the committee, chaired by waitress Frances Stafford, devoted itself to "educating women who have union-earned dollars to spend, as to where and how to spend them." During strikes, the committees escalated their "educational tactics." One devised a tactic called the "button game": shoppers were to go to stores in the busy hours, fill their carts with merchandise, and then demand a clerk wearing the Union button. In eating places, supporters relied on somewhat different tactics. Helen Jaye, a San Francisco waitress in the 1930s, recalled one approach: "The people who into the cafeteria . . . were members of the ILGWU and they . . . gave [the owner] the very dickens. I remember a couple of men [took] their up to the cash register and just dumped them on the floor."

--from Dishing It Out: Waitresses and Their Unions in the Twentieth Century, by Dorothy Sue Cobble (1991: University of Illinois Press: Urbana and Chicago)

Dishing It Out: Waitresses and Their Unions in the Twentieth Century