Mt. Zion Nursing School: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

m (Protected "Mt. Zion Nursing School" ([Edit=Allow only administrators] (indefinite) [Move=Allow only administrators] (indefinite))) |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 14:56, 27 September 2021

I was there . . .

by Betty DeLucchi

Excerpted from Betty June: My Life During the Great Depression and World War II: 1926 to 1946, self-published, Pasadena, CA: 2020

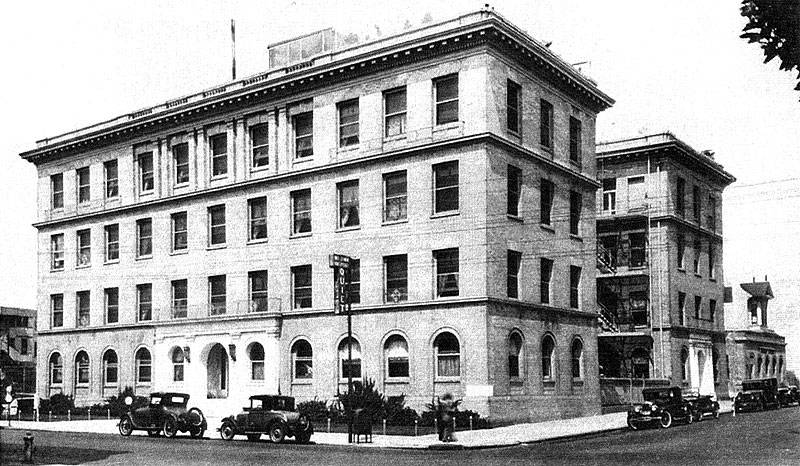

Mt. Zion Hospital, c. 1920s.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

It was a happy day when I received a letter of acceptance to the Mount Zion Hospital School of Nursing. The letter was addressed to me and my parents to attend a reception on a given date — to be held in the living room of the nurses' residence on Sutter Street in San Francisco. We set the date and planned to attend. While anticipating the day when I would leave home, I continued doing ordinary things around the house and to work at Eitel McCullough. The days gradually rolled around to the first week of September, 1943.

The atmosphere in the house was subdued and quiet during those few weeks. All the talking and discussions had been said; further discussion just didn't happen and didn't seem to be needed. I was not overly concerned about anything — not even about leaving home. I looked forward to nursing school as a welcome change, but otherwise it was a matter of fact — a necessity and just "the next thing to do". I wondered whether there was something wrong with me, that I didn't have feelings of apprehension or worry. I was just waiting for the departure day.

Early afternoon arrived on the day to leave. After putting my new baby brother David in the back seat of the car to sleep, Mother got into the driver's seat and I sat in the front seat next to her. Mother was a good driver and accustomed to going anywhere she liked, including into San Francisco. It was as if we were going to the grocery store to buy a loaf of bread or a sack of potatoes — no fuss, no extra movements — and no extra words. In fact there was an audible silence! The car motor started and we backed out of the driveway. I noticed with silent surprise that Mother was wearing a house-dress — clean and neat, but nothing special. She wasn't wearing makeup as she sometimes did on special occasions. For this trip, I wore a blouse and a skirt.

In spite of gasoline rationing, the tank was full and the tires were full of air. My father had been keeping the car in good working order in spite of war-time shortages so we felt assured a safe trip.

Mother and I sensed a kind of apprehension about what was happening. We knew this day was the final one before I entered nursing school. I felt sorry that neither of us seemed to want to talk about it. I wondered why she didn't leave David with a neighbor but I thought it would offend her if I suggested leaving him home. I do not recall any encouraging words or comments of any kind from my father as he left for work that morning.

Going to nursing school was not exactly what I always had in mind but since there was no money or ever the idea of me going to college, I had to admit I was lucky to have the opportunity to learn a skill — one that would lead to a profession. It was time for me to move out and seek my own goals.

Now that my application was accepted, and the interviews and examinations all done, I was on my way. My father had said little except he was glad I would get an education and "that is something nobody can take away from you." I understood his meaning and was happy that he seemed satisfied. He did say that he would have preferred that I had chosen another hospital/school that was not Jewish. There wasn't any reason for me to avoid going to a Jewish hospital. I had explored other opportunities and this was the best choice for me. I had selected Mount Zion over three other available choices because it offered a generalized education for care of all ages of patients, not just children or a particular social group; it was a general hospital. My first choice would have been to go to the University of California School of Nursing but it required two years of prior education, which I didn't have.

Mother had little advice for me except a warning: "Don't become hard, Betty, don't become hordl” She repeated that phrase several times during the weeks leading up to my departure. I didn't understand those words but the tone of her voice led me to assume that, at some time or other, she had had an unhappy experience with a care giver. Possibly someone might have treated her unsympathetically. I didn't worry about it too much; 1 was confident that I would become a good nurse.

As we rode along, I was thinking back to my interview with Miss Jennings, the Director of Nurses, a month or so previously. It had been very comfortable. She presented a welcoming attitude and appeared genuinely pleased to receive my application. The program at Mount Zion Hospital School of Nursing was a three-year course — changed from the previously required four years of study. Upon completion, I would be eligible to take the California State Board Examination for Registered Nurses.

We arrived in San Francisco on Sutter Street outside the Nurses' residence building. The hospital is around the corner of Post and Divisadero streets. Mother stopped the car in the street and sat momentarily silent. Baby David had awakened and she put him in the front seat next to her. She remained in the car, giving no indication that she would park the car or that she would go into the building with me. I asked her if she was coming with me. She said, "That's OK, I'll go in some other time." I kissed her on the cheek and got out of the car.

There were no streetcars passing at that moment nor other traffic, so carrying one small suitcase, I walked across the street to the front entrance of the tall handsome building. As I rang the doorbell, I turned and waved farewell. I was not happy. I felt very alone and I was sad. Whenever I thought about it later, I wished those moments could have been different. I think Mother probably felt the same way.

The world was strangely still. I wanted my mother to go in with me and I wondered why she didn't. I thought she was embarrassed to have a little baby at her side (Mother was 44 years old) and maybe I was embarrassed too. (I was 19 years old.) I was ashamed of myself because I felt selfish for not being willing to share her with anyone else on that special day.

I entered the lobby and was greeted by two smiling people. Off to the right was a large crowded room. I realized they were my fellow students with their mothers.

Everyone was busy talking, sipping tea and eating little cakes. I felt uncomfortable and alone. I looked around studying the faces of young ladies who would soon be my friends. I didn't notice anyone in particular. I didn't see any children. Everyone was dressed well; most of the ladies wore hats which was the standard fashion in San Francisco. There was a stack of suitcases in the lobby and I thought, "Well, everyone is prepared to stay a while!" I sat down off to one side where I could silently observe my surroundings. Pretty soon I was served tea and a cookie. Then someone escorted me to meet the lady serving tea; she was the house mother. I wondered what her role would be. She smiled as she greeted me. I was not too happy so all the smiles and cheerful chatter seemed incongruous.

Eventually, I was introduced to an upper-classman who was to be my "big sister". I was pleased to meet her as she appeared genuinely interested in my welfare. I thought, "She must be a good nurse". She showed me to my room and helped me find my way through the hallways and how to use the elevator, and to tell me some of the rules. She said, "lights out at 10:00 pm". I learned where to find the showers and to locate my student uniforms.

After all the mothers departed, the students lingered in the lobby exchanging friendly chatter. I approached one blonde girl and asked, "Are you from San Francisco?" She replied, "Yes, I have lived here all my life." She asked my name. Her name was Etta. Upon learning that I was not familiar with the city she said, "On our time off, perhaps I can show you some of the interesting parts." I welcomed this, but most of all I was happy to meet a new friend. We all spent the remainder of the afternoon getting acquainted before we went to dinner.

We went out a side door of the Nursing Residence and followed an outdoor passage to the dining room in the main hospital building. It was natural to strike up conversations while eating dinner. A dark haired girl sitting next to me said, "My name is Eleanor. I am happy to know you." She asked, "Do you like the uniforms we have to wear?" It turned out that none of us liked the plain blue straight dresses we would be wearing. But then, we accepted this as only one of the first requirements we would have to endure. One of the upper class students who was with us at dinner said, "You will be wearing plain white caps, but they will be earned and worn only after you have completed six months of satisfactory learning." To receive a cap, we realized then, was a sign of being a real nurse, and was anticipated by us all.

We were expected to supply our own white shoes and white stockings. Because of the war, stockings of any kind were hard to find in the stores. I found some that were made of sheer cotton; none of us was able to find nylons. Flat shoes were frowned upon so I purchased "cubed" heels which were about one inch high. I didn't pay too much attention to how they looked; they were comfortable and made me feel a little taller.

The following day, we had a more thorough tour of our new residence. Our rooms were in a seven story building. Each student had her own room, furnished with a single bed, a dresser and a desk and chair. Each room had a window, a closet and a sink suitable for morning dressing.

In the residence building, aside from the front entry and front lounge on the first floor, there was a large auditorium with a stage at one end with a piano. The auditorium floor did not have affixed seats so I could see it could be used for dances and other social events. There were two classrooms on the main floor as well as a fully equipped kitchen. I eventually saw all of these places used for a variety of functions.

Only one elevator was needed to carry us up to the floor of our room. Each year students moved up one or two floors, depending on the space. Eventually the more senior classmates occupied the sixth and seventh floors. The seventh floor was special because half of it was classroom space to learn bedside care procedures. There was also a roof garden and a comfortable space outside for sunbathing when there was time — and when there was sun!

In a room on the third floor, not shown to me at first, I found large tables and a sewing machine. While enrolled in school, I spent some lovely hours there peacefully making dresses for myself.

The first six months were occupied with lectures on basic nursing duties as well as learning how to do bedside procedures. Students were required to work six days a week and, after the initial learning period, would be assigned to medical and surgical floors — that is, care of patients with surgical or medical diseases or operations. Eventually we rotated through all the departments including Surgery, Obstetrics, Pediatric and Nursery, plus work in the Clinic (a separate building) as well as auxiliary departments as Central Supply and the Diet Kitchen.

We became apprehensive about our first day "on the floor" which is when we would be responsible for patient care. There were rumors about some of the head nurses, who were very strict. One in particular, named Kerzic, was a tall, severe looking woman in a very white and very stiffly starched uniform that made swishing noises as she walked. I wasn't with the three or four students first assigned to her floor as they assembled in the hallway outside of the chart room. I think they were actually shaking with fear! Abruptly, the feared nurse came out to them and demanded, "Well, are you going to do your nursing in the hallway?"

We went about our first day taking care of patients. At first, I felt unsure that I would do everything correctly. To ease my nervousness and worry, I pretended the person I was caring for was my mother — that is, someone I knew and who would approve of whatever I did.

The chart room on all the stations was a room separate from others and separate from the hallways. This is where patient charts were kept, as well as cupboards with space for supplies and for dispensing medications. Beginning students would not be responsible for dispensing medicines until after we passed six months of classroom work including study of pharmacology. After that, each nurse was responsible for performing all procedures for patients assigned to her care and administering medications ordered by the attending physician.

In the chart room we sat on stools to record in print (not cursive) information in the patients' charts — their vital signs of temperature, pulse, etc., and care and treatments administered. It came as a surprise that we were expected to stop our work and stand up whenever a doctor entered the room. We quickly learned that doctors were the elite, privileged members of the hospital staff, and respect must be demonstrated by our standing in their presence.

In class, we started our study of anatomy and systems of the body. Also, we were assigned our working hours. These hours would usually be 7am to 3pm, 3pm to 11pm, or a split shift of two four-hour periods: 7-11 morning, 3-7 afternoon, or 7-11 evening. Additionally, we were eventually expected to do our share of night duty, 11pm to 7am. Most of us accepted these conditions. But a few young ladies in my group didn't like to hear those details described to us. One of them spoke up and said, "Those hours are inhuman!" She continued: "I don't think it is fair to ask us to work all night and only have one day off every six or seven days!" She was adamant in her defiance. She became even more alarmed when she found we would receive a stipend of only $10 each month for the first year, $15 during the second year and $25 in the final third year. The following day she submitted a resignation letter and left. She said, "I will prefer working in a defense factory."

Several others followed her and left school. Most of us accepted the proposed conditions and considered it a privilege to learn a profession — one sponsored by the government. Before the U.S. Nurse Cadet Corps program in which we participated, nursing schools required a substantial tuition, and also were more like nunneries, where young ladies committed their lives to the service of the institution. Previously, duties and rules were accepted without question; nursing students usually spent the entire first year just scrubbing — walls, beds, hallways and whatever there was to scrub!

And we had some carry-overs of those customs. For example, no students were admitted who were married or who had children. If one of us became married or pregnant while in school, she would be required to leave immediately.

One of the first obstacles we encountered when we were finally part of the staff was the resentment of some of the students in previous year classes. They seemed jealous of the privilege granted to us in not being required to serve the first year as they did — one full year of doing only scrubbing. The older students felt they had been cheated. I understood the perplexing situation but I doubt that I would have been willing to spend a full year that way. No doubt the requirement was eliminated because the main goal was to have nurses ready to serve in the army or navy; that need was urgent so classroom work was streamlined.

The government issued each of us a wool uniform and a heavy wool cape. We proudly wore these when we went out in public or traveled home on the trains. The heavy capes were particularly welcome in San Francisco where it is cold on many foggy days.

Getting Oriented at Mt. Zion

Mount Zion Hospital is a rectangular building with four floors. It is on a corner of Post Street near Divisadero in San Francisco. Several marble steps lead up to the front entrance. Within is a large oval counter where one is greeted by a clerk, always present, to direct people to wherever they wish to go.

A hallway runs from the counter back to an exit on the first floor where the Clinic is located. On the main floor are the administration offices and a conference room, as well as the dining room, kitchen, x-ray department, pharmacy and another small area used for emergency care. A side exit leads to a pathway to the student nurses' residence.

The second floor, south side (front of the building) is for medical patients with private and semi-private rooms, two four-bed wards and a central hallway leading back to the north section. On the north part of the second floor are two twelve-bed wards, several semi-private rooms, and storage and equipment closets. The third floor is similarly arranged but it is for care of surgical patients. On the central hallway leading from south to north is where Central Supply is located. On the fourth floor, a large area is devoted to space for pediatric care; there are also several private and semi-private rooms, usually for adult or teen-aged patients. Each department had a nurses' station, utility rooms and a kitchen where patient meals were delivered via a dumbwaiter.

The south side of the hospital was considered "private" while the beds on the north were more for general patients. Large wards were not unusual in the 1940s. The twelve-bed wards were particularly interesting. Each bed was separated by a curtain. There were beds along the outer walls and beds in the central part; this was separated by glass partitions. Female patients were on the east side, male patients on the west side. Second and third floors were similarly arranged. There were also one or two private rooms and two four-bed wards, baths and some extra rooms for linens and equipment.

One of the features we appreciated was the completely separate room for the nurses' station, where privacy was needed to do accurate recording and medication preparation. The main elevator was located on the south side and used for most all transportation up and down. The fourth floor is where the surgical suite was located, on the north side where daylight was plentiful. On the south side was for pediatric patients. This area also had lots of exterior windows; the beds and cribs were separated by glass partitions. Most of the time almost all the beds were occupied. The total patient occupancy was about two hundred and fifty.

The basement was used by the pathologist and for storing equipment like fracture beds and oxygen tanks. Another freight elevator was located somewhere at the rear (north) side.

The clinic was a separate building found at the exit on the first floor. The office for the Director of Nurses was at the front east corner. There was usually no reason to go there unless one of us broke the rules, like returning home after midnight or being late on duty. The director was a severe looking woman with jet-black hair. She frightened me to death. Should I see her approaching me on the pathway from the nurses' residence, I would practice saying to myself, "Good morning, Miss Jennings" but when we came close I would always say the wrong thing. I might say, "Good evening, Miss Jennings". Then I would admonish myself for being so silly!

I suppose there was parking space for the doctors and visitors but I don't know where. Interns and resident physicians lived in a small building next door. We students were forbidden to go there, or to date the interns. Somewhere at the rear of the nurses' residence was the laundry and some other work spaces.

The hospital was conveniently located. As with almost everywhere in San Francisco, transportation is convenient. Street cars were fast and used by everyone except the doctors.

Capping Ceremony After Six Months

Following the probationary first six months — it was now February, 1944 — I was officially accepted into the U.S. Nurse Cadet Corps. By this time several young ladies in our original group had dropped out of the program. They had various reasons for not continuing. I think the primary reason was the time required to be on duty without more days off. Another reason was the idea that we would eventually be working split shifts as well as the night hours. None of those reasons affected me; I was eager to acquire the skills and knowledge to be gainfully employed. I was only faintly aware of all the directions a degree in nursing could allow, but for the moment I was satisfied.

With my classmates, I shared the willingness and desire to join the Army Nurse Corps if the war continued after our graduation.

After the first six months of schooling, we would begin wearing a cap — the symbol of becoming a nurse. The Capping Ceremony was a milestone, and quite a formal affair. Many of the parents came to see their daughters receive a cap. My parents were not able to be there. The ceremony was rather emotional because it signified that we had chosen our life's path, and would dedicate the next two and a half years to very hard work.

The caps for our school were very plain. They were delivered to our rooms from the laundry as a heavily starched white flat piece of fabric with a wide hem, needing folding. Folding a flat piece of cloth so that it could be worn on our heads was rather tricky but after a little practice it was soon mastered. We proudly put them on and posed for a formal photo. Some schools of nursing required a black stripe on the cap to designate senior students but in our institution no distinction was made.

After the capping ceremony everyone settled in to our life. We became serious students and close friends. By this time, most of us had made our rooms comfortable — surrounding ourselves with things we liked. Some of us had radios; a few students had phonographs so they could listen to music of their choice. For amusement we played badminton or table tennis.

Once in a while, we organized a small party in the kitchen on the first floor, but mostly we studied and prepared for classes and tests. Life in the residence was full of lively conversation after we were off duty. We liked describing our experiences of the day as well as catching up on the news.

Betty and her sister nursing students at a restaurant on Broadway, 1945.

Photo: Betty DeLucchi

In April, like most everyone, we were saddened by the news of FDR's death (April 4, 1944). We went to see the newsreels and saw pictures of the train carrying his casket as it passed through the towns from Florida to Washington, D.C., people lining the railway to view the car carrying President Roosevelt's casket. In the film everyone was crying, and we cried too.

We soon had a new president. We wondered how Mr. Truman would carry out the rest of term and hopefully bring an end to the war. One of the most important things that was about to happen, on June, 4, 1944: D-Day, when the Allied invasion into northern Europe began. We wished FDR could have lived to see that day!

My close friend, Etta, had been particularly concerned during the recent weeks because she and her family had not heard from her brother who was in the U.S. Air Force. They were accustomed to hearing from him fairly regularly. She found out later that while he was stationed in England, he was busy doing photo reconnaissance flights over the English Channel and the Coast of Normandy. She learned that he had been seated in the nose of a B-25 with cameras from where he was afforded a full view of the beaches and defense installations.

In the weeks following the invasion, we were thrilled to see newsreels showing the massive effort to invade Europe. To liberate the people and to renew hope for the ultimate defeat of Hitler was like a dream come true. However, we had no idea about how long that would take. Unfortunately, Allied dominance in Europe took longer and sacrificed many more lives than one could have imagined.

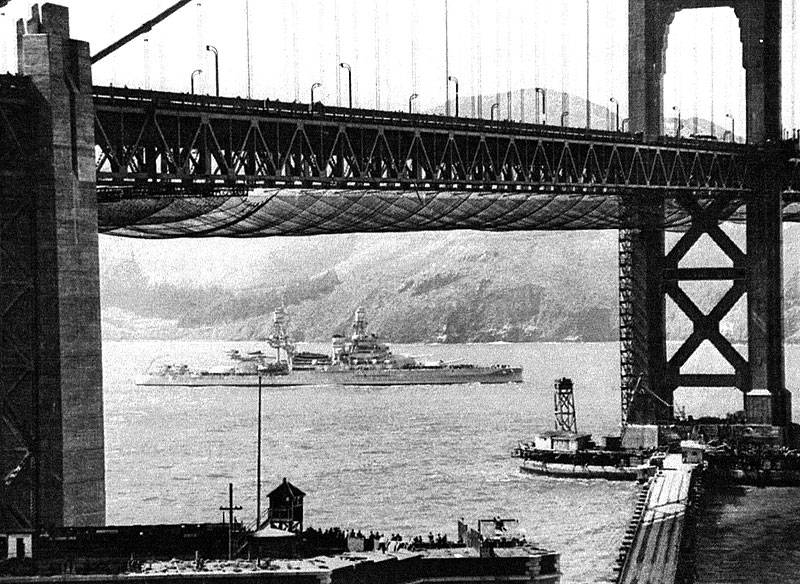

Warship cruises under Golden Gate Bridge as seen from the bluffs south of Fort Point during WWII.

Photo: Betty DeLucchi

Patient Care and Procedure

At 5:30 a.m. we heard a bell sound — the signal to awaken and dress. It took some effort to get used to that early hour and to get moving for the day's activity ahead. We assembled in the lobby of the Nurses' residence at 6 a.m. before going to breakfast. The house mother was always present and she looked at our uniforms and caps to see that everything was clean and correct. After breakfast we each went to our assigned area to work.

We applied ourselves diligently to each day's responsibilities and learning challenges. We witnessed procedures that would be vastly different from nursing practices only a few years later. We could hardly imagine the changes that would happen in the future. As the months progressed we became familiar with the terminology and general function of all the body systems. Lectures accompanied reading assignments, and we learned to read laboratory reports so we could interpret basic norms and diversions that occur with different diseases.

Included with these basic scientific studies was acquiring hands-on skills for setting up and carry out procedures using all types of equipment. I don't think we were aware at the time how primitive some of these were. For example, this was long before plastics — all gloves were red rubber. When we worked in Central Supply, where all basic supplies were cleaned and dispensed, one job was to examine all used gloves. After we examined them for holes and sizes, we discarded the faulty ones, washed and dried the good ones then put them in pairs. Then we wrapped them in cloths before sterilization. For that, they were put into an autoclave (a large machine specifically for the use of sterilizing equipment and instruments).

The central supply was also where we received used syringes and needles. We examined these to assure that the glass was not broken or cracked and then correctly paired the barrel section with the plunger. These were washed and dried, then wrapped in cloths and sterilized. The care of needles required close examination and manually grinding off burrs so they would be sharp. Everything was labeled so it could be stored and dispensed efficiently. As our learning skills advanced, other duties were added in the Central Supply. Not only did we have to learn about the instruments, we were also responsible for matching and cross-matching blood and making it ready for transfusion.

A usual job was to wash and sterilize all the glass thermometers. After washing, they were put in a bath of liquid for 30 minutes that sanitized them. Sometimes one was broken and the mercury spilled out. We were instructed to pick up and save the mercury because it was used in a "Miller-Abbot" tube — a special procedure performed by the doctors to diagnose bowel opacity.

With rare exception, patients admitted to the hospital required in-bed care; very few were ambulatory. Even if patients were able to walk, this was just not what they did. Even post-partum patients, fully able according to today's standards, were expected to remain in bed until the doctor wrote specific order for something different. For example, the usual post-partum care, required women to remain in the hospital and in bed for a full week after delivering their babies. In the years immediately preceding this time, it was the custom for women to remain immobile for two weeks! Caesarean Sections were performed only in the case of emergency, which did not occur frequently.

The usual day care for patients was for them to receive oral hygiene in bed — washing teeth, face and hands before breakfast. After breakfast was the time for administration of required treatments and a bed bath. Doctors usually visited sometime in the mornings. Other procedures might be ordered, such as transporting patients to X-ray department, lab work or doing nursing care procedures such as a Gavage. This was for treatment of sore throat requiring the patient, while sitting up in bed, to be draped with a red rubber apron and allowing a steady stream of warm water by way of a large tube being directed into the back of the throat! As you can imagine, water splashed everywhere!

Sometimes we had to mix a compound using different grains. On a counter in the Utility Kitchen were large labeled jars of different grains — oats, corn, wheat or mustard seed — from which "plasters" were made. Grain and water were mixed into a paste and spread onto a clean cloth. The mixing of grain with water causes it to generate heat. This was then carried to the bedside and placed on the patient's chest; it was a treatment for pleurisy or pneumonia. This was not unknown to many homemakers from previous generations who would prepare and apply plasters made from grains stored in kitchens.

The Utility Kitchen also had a refrigerator with extra nourishment — custard, milk and fruit juice — to be served to patients mid-morning or upon request. It was kind of a ritual.

These procedures were part of the regular protocol. Future medical care with the use of plastics and antibiotics were still beyond our imagination. One of the patients I cared for had Hypertension. I understood she had high blood pressure but I didn't know what the implications or the complications might be. According to medicine at that time, the treatment of choice was to keep her in a quiet and darkened room. Strangely, this was also a recommendation for people suffering from pneumonia and probably other less well understood ailments.

One of the patients I cared for had Bright's disease. She died within about four weeks of her hospitalization. It is astounding to compare the medical treatments of what we learned with accepted practice today. After antibiotics came into use years later, the disease from which she suffered (kidney failure) became curable.

When a hypodermic injection was needed — usually for relief of pain or as a pre-medication before surgery — the procedure was quite detailed. First a sterile glass syringe was unwrapped from a cloth, a needle from another "sterile" wrapper was unveiled and, with our fingers, attached to the syringe. Then we would pick up the little scopolamine pill (if ordered) and drop it into the barrel of the syringe. Then we pushed the plunger deep enough to the barrel to partially crush the pill. Water was put in an open spoon, held in a bracket over an alcohol lamp. Using a flint, we ignited the flame of the lamp. When the water was boiling and thus sterile, we drew it into the syringe. Usually another medication was added from an ampoule. In that case, the ampoule was cleaned with an alcohol sponge before breaking it open and the contents withdrawn into the syringe. We gave everything a good shake to make sure it was mixed and dissolved before it was injected into the patient. We learned which medicines could be mixed with others, the normal doses, and toxic levels.

Some of my classmates cried when learning how to administer an injection. We had to practice on a lemon. Even then, some of us found it hard to put the needle through the outer rind. Learning to "give a shot" quickly and with minimal discomfort to the patient was an art — something we all strove to perfect.

Hospitals like ours did not have piped-in oxygen. Tanks of oxygen were stored in the basement and brought to the patient's bedside and set-up for use — usually by an older man because all the young men were off to war. Nasal cannulas were not yet invented so patients were put under a tent. This was a large canvas and net apparatus that was very awkward and clumsy to set up. It had to be tucked under the head of the mattress to prevent escape of oxygen that was pumped into the tent from the pressure in the tank. The tent was uncomfortable for the patient as they felt very confined and it was difficult to communicate and learn their wishes and concerns. Frequently, we asked the patient to write on a tablet a description of their need.

When steam inhalation was ordered by a doctor for patient care, we heated water in a big flask until it was boiling hot. Then with special asbestos-gloved hands we carried the flask to the bedside as fast as possible where the still escaping steam vapors could be held close enough for the patient to inhale to get some breathing relief!

The procedures we students learned have been all but forgotten now. One strange process we learned was how to set up a Waganstein Suction. This was used whenever a patient needed suction to drain their stomach contents or remove fluid from the gut. It was a complex system consisting of three bottles. As fluid (water) was drained from the upper bottle drained through red rubber tubing to a bottle at a lower level (on the floor) and a third bottle somewhere between the two, with connecting rubber tubes was empty, creating a vacuum. We learned to set these up and get them functioning at a patient's bedside; we did not have suction machines that operated with electricity.

Neither nurses nor students were permitted to start intravenous injections. Infusion solutions came prepared in glass bottles with a port for attaching a red rubber tube. A straight needle was used to insert into a vein. This was done by a physician only — not a nurse! The rate of drip was controlled by a small folded piece of metal that came from the top of the bottle. Students were allowed to monitor the rate of the drip but not to remove the needle once the fluid had been completely infused.

Intravenous (IV) infusions were not done as frequently as they are today and I think we only had 5% dextrose in water and Normal Saline. The same procedure was used when a unit of blood was ordered. I did not witness any infusions given to babies but student nurses were taught to give subcutaneous injections to infants of 10 to 20 cc. of normal saline. This fluid was usually injected into the back scapular area. It was strange and looked awful but the babies didn't seem to mind.

The Utility Room is where bedpans were put though a hot water and steam enclosure where they could be "sterilized" after each use. Miss Coleman, our "clinics" instructor emphasized, "When you carry a bedpan to a patient's bed, do it with dignity! We carried bedpans covered with a very white clean cloth so it was not difficult.

Student nurses worked four or five weeks in the Clinic during training, dealing with outpatients for minor problems and periodic medication and treatment. We didn't like the interior of the Clinic because it was dingy and strange. Large jars of different colored fluids were suspended from the ceiling; this fluid was used for bladder irrigations. I never imagined such a thing before I entered nursing school and I doubt any of my fellow students had imagined it either! We did our assignment there grudgingly and were happy when it was over. We seldom made patient contact and were satisfied to do mundane chores like stocking shelves and keeping things orderly. Doctors appeared to be familiar with their patients and were satisfied to do procedures without our assistance.

On days when few patients came for treatments, students were given the task of making bandages and pledges of cotton, and rolling gauze so that it could be sterilized and used as sponges in surgery. One day, in a hallway in the Clinic, I was astonished to pass near a table on which a very large man was standing. He was not fat — just large — like one can imagine a giant. I noticed his handsome face and body and particularly his legs which were bare and fully exposed. His long legs were muscular but rippled with varicose veins. From his general appearance, I thought he could play the part of a gladiator in a Hollywood movie.

Several doctors were in attendance. I could overhear their muffled voices as they were apparently discussing the procedure they were about to perform. They were preparing to infuse his varicose veins with gold. Injection of gold was a treatment of choice. I thought, "Maybe he is from Hollywood!" Not everyone could afford such care. I learned later that infusions of gold into joints was also tried as a remedy for arthritis.