Problem with Parklets: Difference between revisions

(added photos) |

m (fixed Erica's name) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | '''<font face = Papyrus> <font color = maroon> <font size = 4>Historical Essay</font></font> </font>''' | ||

''by | ''by Erica Dawn Lyle'' | ||

[[Image:Parklet-4-barrell 0259.jpg]] | [[Image:Parklet-4-barrell 0259.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 19:35, 19 June 2023

Historical Essay

by Erica Dawn Lyle

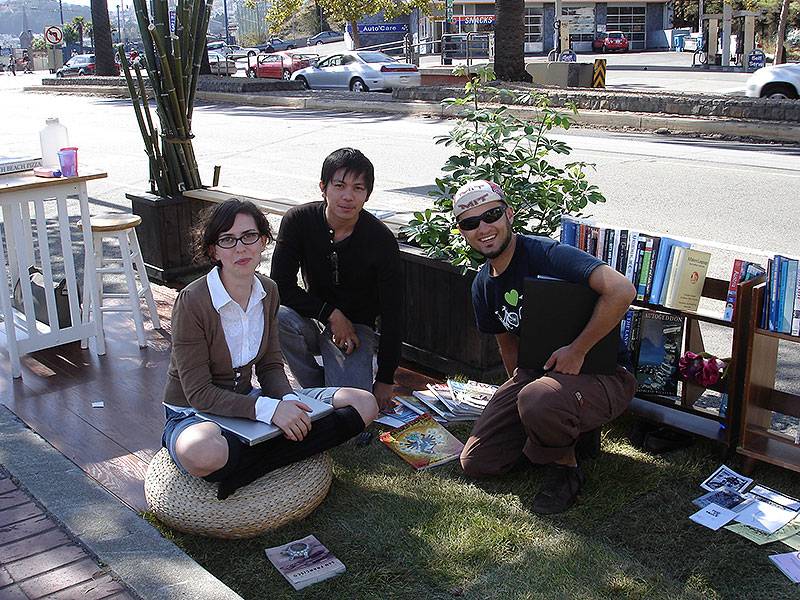

Parklet in front of Four Barrell Coffee on Valencia between 14th and 15th streets.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Park-ing Day, Sept. 2007—what was once a radical intervention into public space has become commonplace in the years since.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Parking Day float, 2007.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The city’s response to this collapse of its public spaces has been to encourage the development and proliferation of an innovative kind of post-public space. In 2010, the very year that it became illegal to sit on a public sidewalk in San Francisco, the city also began issuing permits for the creation of so-called parklets.

Claimed by the growing Tactical Urbanist movement as one of its greatest successes, parklets were born in 2005 in San Francisco, when an arts group simply rolled out a patch of fake grass across a city-owned parking spot and placed some chairs and a potted tree atop it. There was a sign instructing passersby to put coins in the parking meter if they wanted to keep the new park in existence. Today there are forty-three similar parklets in the city, individually designed by top local firms and neighborhood architects, and all officially permitted by the city.

Park-ing Day, 2012, on Valencia Street.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

But did that parking meter ever really go away? While it is still literally and legally true that the parklets are public space reclaimed from use by private automobiles, in practice these so-called parks are nothing more than outdoor seating areas for the restaurants and cafes in front of which they are invariably located. (Only one parklet is in front of a private residence; the rest are administered by commercial enterprises.) Thus in another bait and switch the first parklet’s friendly invitation to passersby to simply stop and linger on a lawn has been quickly replaced with a new kind of for-profit space. In the process, the parklets—privately sponsored, funded, and maintained—have become the perfect expression of our neoliberal age. Anyone can have their own park, just big enough for themselves and their friends, if they pay for it out of their own pocket.

As traditional public space in the city becomes untenable due to economic inequality, we see an economically and racially homogenous segment of the population retreat to these spaces that are legally but not legibly public. The homogeneity of these populations and their apparent access to an abundance of leisure time and disposable income present a powerful message of non-inclusiveness to the city’s people of color, the urban poor, and the homeless, who in contrast have been warned loud and clear in recent years not to take it for granted that they can sit anywhere in public without risking arrest or police harassment. In short, the parklet is the Google Bus of public space.

Facebook and Google buses cruise past the parklet in front the worker-owned cooperative bakery Arizmendi in 2016.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

A Park-ing Day library on Market Street near Duboce, 2007. Innocent times!

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The original "astroturf" organization!

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Holding it down on Mission between 9th and 10th, 2007.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Excerpted from Streetopia, in the essay "The Uses of Market Street"

See other parts of this essay: