BARBARY COAST: Difference between revisions

(added new photo) |

(added lost landscapes video) |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

''Photos: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | ''Photos: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library'' | ||

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/barbary-coast-1914-from-lost-landscapes-no-1" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe> | |||

'''Russian sailors visit various establishments in the Barbary Coast, 1914.''' | |||

''Video: from "Lost Landscapes #1, 2007" courtesy Prelinger Archive'' | |||

[[Image:Barbary Coast circa 1955 wnp25.1231.jpg|800px]] | [[Image:Barbary Coast circa 1955 wnp25.1231.jpg|800px]] | ||

Revision as of 21:07, 3 November 2023

Historical Essay

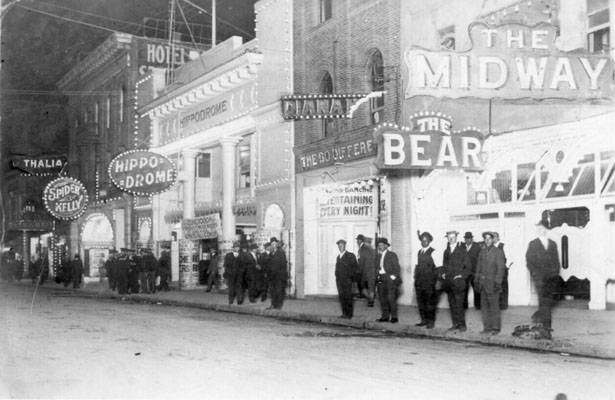

Barbary Coast, 1909.

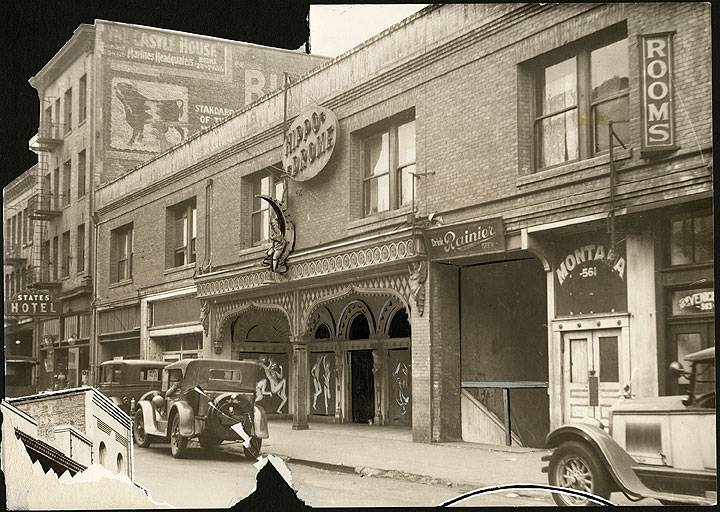

The Hippodrome by day, c. 1900-1920.

Photos: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/barbary-coast-1914-from-lost-landscapes-no-1" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Russian sailors visit various establishments in the Barbary Coast, 1914.

Video: from "Lost Landscapes #1, 2007" courtesy Prelinger Archive

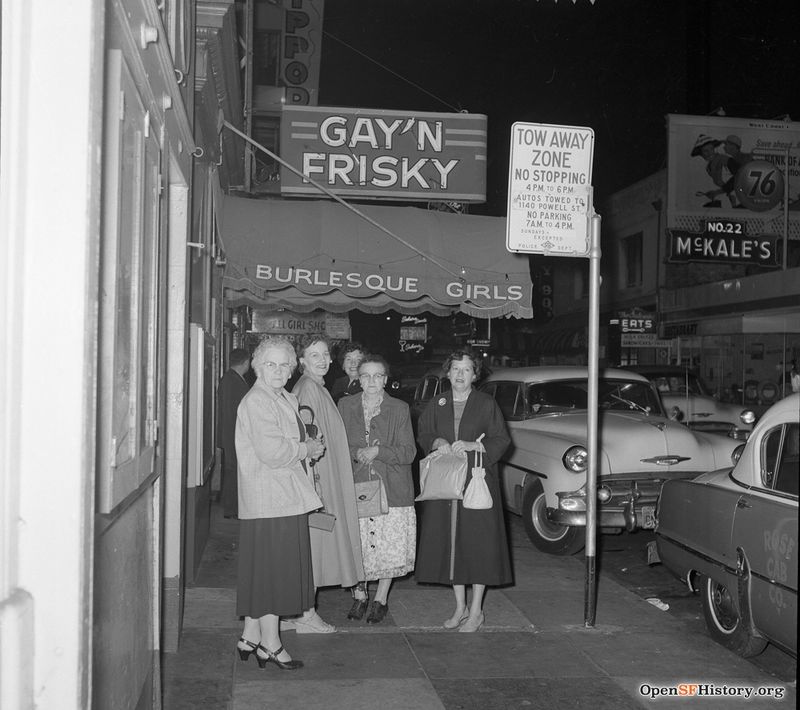

The enduring attraction of the Barbary Coast lasted well into the 20th century, seen here in 1955.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp25.1231

Tourists converge on the Gay 'n Frisky c. 1955.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp28.2344

1849: Badly drawn paintings of nude women adorn the walls of the best cafes in the city. Prostitutes begin to arrive from the east. They are frequently auctioned off from the decks of the arriving ships. Cafe owners often hire them to pose nude in displays in the dining halls. Gambling houses were everywhere. At the El Dorado it was reported that $80,000 once changed hands on the turn of a single card. Liquor and female companionship were often provided free of charge by the house as an incentive to frequent patrons.

1860-1880: It was in the mid-1860s that the term "Barbary Coast" came into being. It derived its name from its similarity to the notorious Barbary Coast in Africa, and stretched from Montgomery to Stockton along Pacific Street, with branches off into Kearny and Grant Ave. The area had already been cleaned out twice before by the Vigilantes, but once again it began to grow with dives gambling halls, and houses of prostitution. One particularly dangerous block on Pacific between Kearny and Montgomery was known as Terrific Street. A writer in 1876 described the area:

The Barbary Coast is the haunt of the low and the vile of every kind. The petty thief, the house burglar, the tramp, the whore monger, lewd women, cut-throats, murderers, are all found here. Dance halls and concert-saloons, where blear-eyed men and faded women drink vile liquor, smoke offensive tobacco, engage in vulgar conduct, sing obscene songs and say and do everything to heap upon themselves more degradation, are numerous. Low gambling houses, thronged with riot-loving rowdies, in all stages of intoxication, are there. Opium dens, where heathen Chinese and God-forsaken men and women are sprawled in miscellaneous confusion, disgustingly drowsy or completely overcome, are there. Licentiousness, debauchery, pollution, loathsome disease, insanity from dissipation, misery, poverty, wealth, profanity, blasphemy, and death, are there. And Hell, yawning to receive the putrid mass, is there also.

--from Lights and Shades of San Francisco by Benjamin Estelle Lloyd, 1876.

One of the more colorful and memorable characters of the Barbary Coast was a one-time actor whose only name was Oofty Goofty. Oofty Goofty's great claim to fame was his insensitivity to pain. For many years he made his living along the Barbary Coast by being the willing victim of physical abuse. For ten cents a man might kick Oofty Goofty as hard as he pleased; for a quarter he would let himself be hit with a walking stick; and for fifty cents he would take a blow from a baseball bat.

The Old Hippodrome and Bella Union Dance Halls at 557 Pacific Street between Kearny and Montgomery. Jesse B. Cook on sidewalk, February 1925.

Photo: Jesse Brown Cook collection, online archive of California I0050526A

Hippodrome, early 1930s.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Those who escaped the clutches of the crimps and runners trying to shanghai them frequented the dance halls of the Barbary Coast, where "dancing" with a woman could take any form or degree the patron wished. Those who desired serious drinking could choose from a variety of establishments, the most dangerous of which was The Whale--as tough a bar-room as San Francisco ever boasted. The most famous criminals of the time could frequently be found there, as for the most part, even the police were afraid to enter. Another famous drinking establishment was the Cobweb Palace, run by Abe Warner, a lover of spiders, who let them spin their webs without interference. The webs hung were festooned across the ceiling and down the walls. Liquor was especially cheap at Martin and Horton's, where one of its most infamous patrons was a shy little man who tended to sit unobtrusively at the back of the room. He was in fact, Black Bart, the highway bandit who held up stages with an unloaded gun and always left behind a bit of poetry signed "Black Bart the PO8."

The primary industry of the Barbary Coast was prostitution. Three particular types of brothels were to be found: the cow-yard, which served as both apartment building and brothel; the crib, the lowest and most disreputable of the houses; and the parlor house, whose employees were considered the "aristocracy" of San Francisco's red-light district.

The women who worked in the dives, regardless of their age, were called "pretty waiter girls." They were usually paid $15 to $25 a week to serve as waitresses, entertainers and prostitutes. For a small fee a man could view any pretty waiter girl free of her clothing. During the 1870s one Mexican fandango den dressed its girls in no more than red jackets, black stockings, garters and slippers. This dress code was abandoned in a few weeks due to overwhelming and uncontrollable crowds.

More often than not the owners of these brothels, regardless of what kind of house they operated, came away with great fortunes. The more frequented parlor houses seemed each to have its own speciality. Madame Bertha, who ran a parlor house located in Sacramento Street, in addition to the usual activities of such an establishment, gave organ recitals on Sunday afternoons to specially invited guests. The prostitutes sang popular songs while Madame Bertha accompanied.

Madame Johanna employed three French girls who gave erotic exhibitions and were known as the Three Lively Fleas. She was also the originator of "direct mail advertising" for brothels, sending pictures of the naked girls to specially procured mailing lists.

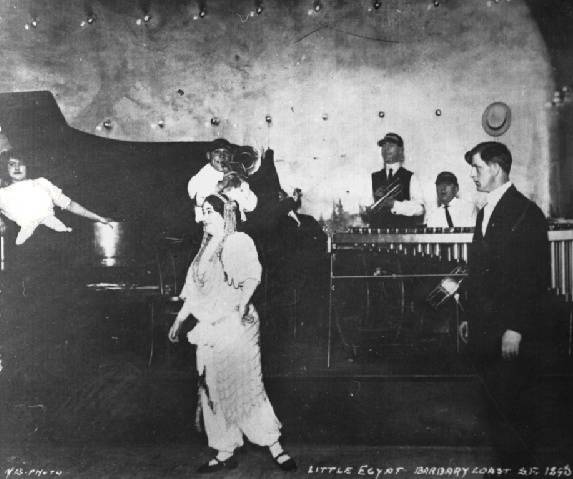

Little Egypt on the Barbary Coast, 1890

Barbary Coast, c. 1890

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp71.1145

The bagnio owned by Madame Gabrielle at Geary and Stockton featured a weekly show in which the participants were black men and white women. Frequently a parlor house had its own particular motto which could be found framed in every room. The motto of a California street house was What is Home Without Mother? Each of the parlor houses in Commercial Street boasted a chamber called the "Virgin Room," where a gullible customer could be accommodated at double or triple the usual price. Usually the room was staffed with a girl young enough, and enough of an actress to simulate fright and bewilderment. She was usually paid slightly more than the other prostitutes.

The Hippodrome in 1890

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

A frequent patron of these house was San Francisco's most notorious murderer of the time, Theodore Durrant. When not frequenting prostitutes or murdering them, Durrant spent his time as a medical student and an assistant superintendent of Sunday school, prominent in the work of the Christian Endeavor Society. His modus operandi was to bring a small bird to the parlor house and at some time during the evening slit its throat and let the blood drip over his body.

In the cribs and cow-yards, customers were not permitted to remove their shoes, or often any garments at all--except for their hats. Only a specific kind of crib, called a "creep joint" permitted the removal of clothing, and the reason for that was in order that an accomplice could steal all his money and valuables. It was, however, customary to leave a shiny new dime in the customer's pocket. The origin of the custom is unknown--perhaps it was left as car-fare.

Cribs were located throughout the Barbary Coast, but black and Hispanic establishments were concentrated on Broadway between Grant and Stockton. The French houses could be found primarily in Commercial Street.

1900: Three blocks of dance halls with the loudest possible music blasting forth from orchestras, steam pianos and gramophones in such establishments as The Living Flea, The Sign of the Red Rooster, Ye Olde Whore Shop. Extended from the foot of Telegraph Hill to the shoreline, largely along Pacific Street and Broadway. The Dew Drop Inn, Canterbury Hall and Opera Comique all specialize in erotica of a high order. Dead Man's Alley, Murder Point and Bull Run form a secret network of tunnels through which people as well as booty were smuggled. The area takes in Chinatown, and Asians are often blamed for this blight on the city.

The San Francisco Examiner, the newspaper owned by William Randolph Hearst, is nicknamed The Whore's Daily Guide and Handy Compendium due to the thinly disguised ads for prostitutes in the classified section.

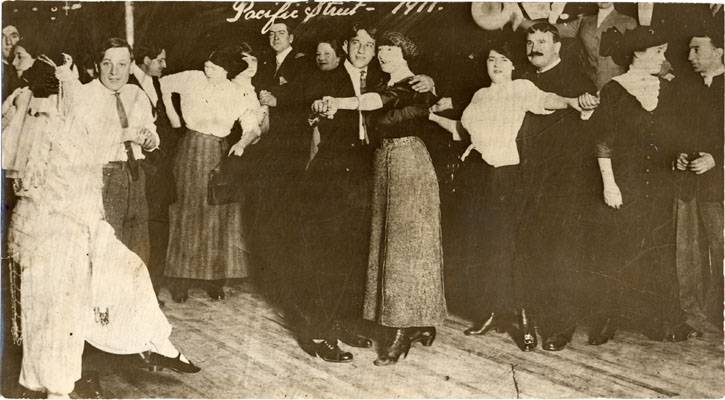

Dancers at Spider Kelly's on the Barbary Coast, 1911.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

The worst of cribs were to be found on Morton Street (now ironically enough called Maiden Lane). The most notorious was the Nymphia on Pacific Street, the Marsicania on Dupont Street (Grant Ave.), and the Municipal Brothel on Jackson Street near Kearny. On a slow night the pimps might sell the privilege of touching a prostitute's breasts for the fee of ten cents. On a good night a prostitute might service as many as a hundred men.

The Nymphia, a three-story building with about a hundred and fifty cubicles on each floor, was erected in 1899. The intention of the owners was to name the place the Hotel Nymphomania and to stock it with women suffering from that condition. When the police refused to permit that name, the owners compromised, calling it the Nymphia. Each female resident was required to remain naked at all times and was obliged to entertain any man who called. For a dime a customer would view the activities in any room through a narrow slit in the door. The place was first raided by police in 1900 and after several legal battles, finally closed down in 1903.

The San Francisco Call described the Marsicania as "one of the vilest dens ever operated in San Francisco." Its population was about 100 prostitutes, each of whom paid $5 a night rental cost. It was opened in 1902 and enjoyed a period of prosperity when the police were legally restrained from blockading or entering the premises except under extreme emergencies. This decision was overturned in 1905 and the Marsicania was forced to close.

On Jackson Street the Municipal Brothel or the Municipal Crib was called so due to the fact that most of its profits went into the pockets of city officials and prominent politicians. It was build in 1904 on the site of the underground Chinese tenement known as the Devil's Kitchen, or (with great sarcasm) the Palace Hotel. The women were graded by floors with the Mexican prostitutes in the basement, and the black women on the fourth floor. In between a variety of nationalities were represented. The Municipal Crib was protected from police raids until the prosecution of former Mayor Eugene Schmitz and Abe Ruef, who had received regular payments from the profits.

When it was at last closed in 1907, the Municipal Crib was the last significant cow-yard to operate in San Francisco. For all intents and purposes the flesh-pits that were the Barbary Coast were wiped off the face of the map by the great earthquake and fire of 1906.

The opium dives, slave-dens, cowyards, parlorhouses, cribs, deadfalls, dance-halls, bar-rooms, melodeons and concert saloons were all turned to ash. The destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, it was called by the clergymen. The day following the great fire, men lined up for blocks in order to patronize the brothels of Oakland. The slave-trade of Chinatown came to an end and the opium dens were never rebuilt. But the entrepeneurs of the Barbary Coast were determined to rebuild the quarter upon the ruins of the old. By 1907 it was once again in full operation.

While the city of San Francisco officially disdained the goings-on of the Barbary Coast, it took a secret pride in this area widely proclaimed as the wickedest town in the U.S.A. After the great earthquake and fire, the Barbary Coast became more of a tourist attraction than its predecessor. Such luminaries as Sarah Bernhardt and ballet dancer Anna Pavlova were known to frequent the area. British poet John Masefield is to have said immediately after disembarking, "Take me to see the Barbary Coast." Dance-floors and variety shows designed to shock the tourists replaced prostitution as the chief business. Indeed, many of the dance crazes that swept America during this period were originated in this section of San Francisco: the turkey trot; the bunny hug; the chicken glide; the Texas Tommy, the pony prance, the grizzly bear, and other varieties of semi-acrobatic dancing. Among the many dance halls on the Barbary Coast, the Thalia, on Pacific between Kearny and Montgomery, remained the most popular. It usually featured a "Salome dancer" or strip-tease artist.

The number of women working on the Barbary Coast during this period ranged from 800 to 3,000. They were paid from $12 to $20 a week to dance and drink with the customers and to appear on stage in ensemble choruses. Many engaged in prostitution but usually in their after hours. Their dress was described as "of the cheapest fabric, many of them torn and stained, none reaching below the knees, and here and there hooks missing and bodices yawning in the back, but always the silk stocking as the inevitable mark of caste." [San Francisco Call, 1911] Often the girls were barely in their teens, and the dance-halls frequently served as recruiting agents for the brothels.

Barbary Coast after the '06 quake

The first dive to open after the earthquake, and perhaps the most notorious establishment on the Barbary Coast of the post-earthquake period, was the Seattle Saloon and Dance Hall, in Pacific St. near Kearny. The women employed there were paid from $15 to $20 a week, and following the custom of an earlier deadfall, they were forbidden from wearing underwear. Advertisements of this feature were discretely passed around the saloons of the city. The women were also paid a slight percentage of the drinks they sold and entitled to half of whatever they might pick from the pockets of their dance partners. (The proprietors often complained that the girls were dishonest in reporting the true amounts they had stolen.) But the women of the Seattle soon developed another source of income by supposedly selling their house keys to drunken patrons who would pay from $1 to $5 each for a key. The keys of course were bogus, and the police soon put an end to this practice after receiving numerous complaints from homeowners about drunken men searching hopelessly in the middle of the night for locks their keys might open.

When the Seattle was sold in 1908, its name was changed to the Dash. The waitresses were replaced by male cross-dressers who for $1 would perform whatever sex act was requested. It was soon revealed that the new managers were two officers of the Superior Court under Judge Carroll Cook. The place was closed six months after it had opened.

1910-1920: In 1911 the Board of Health established a Municipal Clinic which compelled every prostitute to submit to examination and necessary treatment for disease. Prostitutes were required to carry a booklet listing her record of medical examinations, and no woman was permitted inside a brothel without a medical certificate. The Clinic existed for only two years, but in that time reduced venereal disease in the red-light district by 66 percent. The Clinic was fought bitterly by nearly every clergyman in the city. Mayor James Rolph, Jr., who had gone on record as supporting the work of the clinic, eventually succumbed to the political pressure brought to bear by the clergymen and ordered police protection withdrawn from the clinic. Soon afterward the Clinic closed its doors and diseases once again raged unhindered throughout the red-light district.

The defeat of the Union Labor Party in 1911 marked the beginning of the end of the Barbary Coast. Gone was the general feeling of Gold Rush days that San Francisco must remain a "wide-open" city. In 1912 the new Police Commissioner Jesse B. Cook launched a direct attack on the Barbary Coast publishing his plans in the newspapers:

1) All dance-halls and resorts patronized by women in Montgomery Avenue (now Columbus) west of Kearny Street and on both sides of Kearny Street to be abolished.

2) Barkers in front of the dance-halls in Pacific Street to be done away with and glaring electric signs forbidden.

3) No new saloon licenses to be issued until the number had been reduced to 1500 which was to be the limit in future.

4) Raids to be made against the blind pigs.

In February of 1913 another resolution was adopted:

Resolved, That no female shall be employed to sell or solicit the sale of liquor in any premises where liquor is sold at retail to which female visitors or patrons are allowed admittance. The enforcement of this resolution proved completely futile, but it did send out the message that the Barbary Coast of old was not to be tolerated.

But it was the San Francisco Examiner under the leadership of William Randolph Hearst which led the crusade that eventually brought down the Coast. Many churches and welfare organizations promptly jumped on the Examiner's bandwagon, and on September 22, 1913, the Police Commission adopted the following resolution:

Resolved, That after September 30, 1913, no dancing shall be permitted in any cafe, restaurant, or saloon where liquor is sold within the district bounded on the north and east by the Bay, on the south by Clay street, and on the west by Stockton Street. Further Resolved, That no women patrons or women employees shall be permitted in any saloon in the said district. Further Resolved, That no license shall hereafter be renewed upon Pacific Street between Kearny and Sansome Streets, excepting for a straight saloon.

In September of 1913 the Thalia displayed the following sign:

THIS IS A CLEAN PLACE FOR CLEAN PEOPLE -- NO MINORS ALLOWED.

This sign perhaps more than any other signalled the end of the Barbary Coast. Even the most notorious of the dance halls now had trouble attracting enough customers to stay in business.

The Thalia Dance Hall at 732 Pacific Street, with Jesse B. Cook on sidewalk, February 1925.

Photo: Jesse Brown Cook collection, online archive of California I0050528A

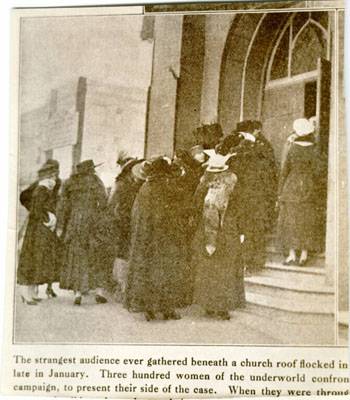

In 1914 the Red-Light Abatement Act gave the city authorities the right to impose civil court actions against any property used for purposes of prostitution. Also during this same time a young Methodist clergyman, Reverend Paul Smith, took it upon himself to launch a tireless campaign against whatever sin and vice yet remained on the Barbary Coast. (It was reported that his sermons were so provocative that prostitutes flocked to the vicinity of his church after the services, where they found eagerly aroused customers). Rev. Smith's campaign against immorality came to a head on a January morning when more than 300 prostitutes dressed and perfumed in their finest marched to the Central Methodist Church to confront the minister. When admitted to the church they posed the question, "How are we to make a living when all the brothels have closed?" The Rev. is said to have replied that he would work tirelessly to establish a minimum-wage law and would assist the women in finding new employment. He claimed that a virtuous woman with children could live on $10 a week. "That's why there's prostitution!" came the reply, at which point the ensemble left the church in disgust.

January 25, 1917, three hundred prostitutes march to Central Methodist Church to protest anti-prostitution campaigning by Rev. Paul Smith.

In 1917 the Supreme Court rendered its final decision on the Red-Light Abatement Act. Dancing was now prohibited in all cafes and restaurants anywhere in the vicinity bordered by Larkin, O'Farrell, Mason and Market; all private booths were removed in establishments where liquor was sold; and unescorted women were to be ejected from such premises. These regulations effectively closed down such notorious Barbary Coast establishments as the Black Cat, the Panama, the Pup, Stack's, Maxim's, the Portola, the Louvre, the Odeon and the Bucket of Blood.

1920s: In one final gasp at life, the Barbary Coast recalling its former glory as the most notorious section of San Francisco, once again attempted to resurrect itself in 1921. The Neptune, Palace, Elko and Olympia again opened their doors, selling near beer and featuring a few dancing girls. But the watchful eye of Mrs. W. B. Hamilton, Chairman of the Clubwomen's Vigilante Committee, soon saw to it these newly opened dens of iniquity were not to be endured. She reported to the newspapers, "I have visited dancing places in Honolulu, Tahiti and various islands of the South Pacific, but I saw nothing in those places more obscene and morally degrading than I saw in the Neptune Palace." The police took immediate action and the Barbary Coast was at last closed down for all time.

Patrons in the Hippodrome, 1934.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

1940s: U.S. military insists on shutting down brothels and bars around the city as tens of thousands of soldiers pour through San Francisco en route to and from the Pacific Theatre of War.

1950s: Mayor George Christopher appoints a beat cop as police chief and Chief Ahern instigates a crackdown on police corruption and vice tolerance.

Pacific Avenue looking west between Montgomery and Kearny, November, 1953.

Photo: C. R. collection

The Old "International Settlement" sign at Kearny and Pacific just before its final removal, June 6, 1957.

Photo: Bancroft Library

International Settlement entry in 1947.

Photo: courtesy Bob Ristelhueber via Facebook

Columbus and Pacific, c. 1955.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp25.2110

1960s: Carol Doda takes off her top at the Condor Club at Broadway and Columbus. She becomes a big celebrity and contributes mightily to San Francisco's now-restored reputation as a town where anything goes.

1970s: Pornography industry gets a big boost by the entry of two Bay Area brothers, the infamous Mitchell Brothers. Their first feature porn film, Behind the Green Door, brings hardcore pornography into wide circulation. Their club on O'Farrell endures hundreds of raids by SFPD Vice officers, but is never shut down. "Lap Dancing" and other forms of nude entertainment are accepted in the City.