Beyond Playing Dead--Playing To Win: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

EvaKnowles (talk | contribs) (added abstract) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

''Photo: Keith Holmes'' | ''Photo: Keith Holmes'' | ||

{| style="color: black; background-color: #F5DA81;" | |||

| colspan="2" |'''The Shock Troupe was a pro-peace guerrilla theater group active during the 1980s. In this flier, they dive deep into the failures of the peace movement and speak to the current moment of nuclear proliferation. Though published in 1983, this flier evokes our current moment for how it grapples with activism and the motivations behind it.''' | |||

|} | |||

WHY are you here? We don't mean to insult your intelligence with the obvious. You're here—as we are too, in part—to show your opposition to the deployment of U.S. nuclear missiles in Europe. In addition, we share alarm at what seems to be a general plunge into conventional war in Central America and the middle east. | WHY are you here? We don't mean to insult your intelligence with the obvious. You're here—as we are too, in part—to show your opposition to the deployment of U.S. nuclear missiles in Europe. In addition, we share alarm at what seems to be a general plunge into conventional war in Central America and the middle east. | ||

Latest revision as of 15:18, 3 July 2024

Primary Source

–Shock Troupe, 1983

1983: Protesting the deployment of "euromissiles" (i.e. U.S. cruise missiles) along the Iron Curtain.

Photo: Keith Holmes

| The Shock Troupe was a pro-peace guerrilla theater group active during the 1980s. In this flier, they dive deep into the failures of the peace movement and speak to the current moment of nuclear proliferation. Though published in 1983, this flier evokes our current moment for how it grapples with activism and the motivations behind it. |

WHY are you here? We don't mean to insult your intelligence with the obvious. You're here—as we are too, in part—to show your opposition to the deployment of U.S. nuclear missiles in Europe. In addition, we share alarm at what seems to be a general plunge into conventional war in Central America and the middle east.

But what about the underlying emotional reasons? Fear, certainly, and understandably. Moral outrage even. Perhaps a bit of guilt. Somewhere, we feel a lingering love of life and its remaining pleasures, now so overwhelmingly threatened. But are those reasons enough?

The peace movement seems to be more or less holding its own. But it ought to be doing better, considering the sheer deadliness of the situation. Why aren't the turnouts larger? What's happened to all those people who marched in June '82? Why are we slowing down when we need to speed up? Recent setbacks include Kohl and Thatcher's victories in Germany and the UK. Mitterand, calling himself a socialist and campaigning for peace, now sends troops to Chad, bombs Lebanon, and threatens to sell fighters to Iraq. Media hysteria over the Korean airliner incident has encouraged Cold War attitudes.

However, we think there are deeper problems, basic flaws in the movement's psychological, political and social strategies.

At this point, knocking the Freeze is like trying to shatter a melted icecube. Since the passage of the Freeze in the House, quickly followed by passage of MX and B1 bomber bills, some ex-Freezeniks have come out against U.S. policy in Central America and joined with anti-interventionists. At Port Chicago last July and elsewhere, a coalition has been trying to show the connections between the nuclear buildup and a new gunboat diplomacy.

THE PROTEST GHETTO

THIS effort has been moderately successful. Yet, while it has drawn together thousands of those already active, it has not brought in large numbers of new people. Nor has it broadened and deepened the movement's social base. The U.S. movement continues to be dominated by white, college-educated technical and professional workers (with a good number of dropouts), aged around 25-35.

The movement's answer to this problem so far has been outreach to progressive union officials and tacking the demand for Jobs onto the ever-growing list. This piling issue on issue doesn't solve the fundamental problem. The movement has been powered from the beginning primarily by fear and indignation. As emotional fuel, these feelings burn hot, but fast. The initial horror wears off, to be replaced by a creeping numbness, an exhaustion under the barrage of atrocities howling from the headlines. For the seasoned activist, other feelings begin to take precedence. Bitterness is tamped down, along with guilt and defiance, finally becoming force of habit. Protest turns into a way of life. A culture develops around it, a cluster of attitudes and behaviors which isolate the activist from "ordinary" people.

In itself, this is neither altogether avoidable nor necessarily fatal. The danger is that these activists, protesting on behalf of "humanity," "the children," "the biosphere," are often terribly out of touch with the deeper sources of rebellious social movements. These are the "for-themselves" motivations that alone provoke masses of people to break out of their imposed routines and challenge the status quo.

It is not fear that finally impels millions into action, but rage—rage and desire. Rage against the thousand gross and petty humiliations they are subjected to daily at the hands of employers and bureaucrats. Rage at the stupidity of their work and the emptiness of their leisure, at coldness and isolation. Rage against the accelerating destruction of the natural and social environment. Rage against burial in concrete—and desire for meaning, adventure, community, human contact and the awakening of the senses. It is not only nukes that menace what is left of life, but the whole structure of modern society, beginning with the obsolescent machinery of work-to-pay-to-work which we call "the economy." Only a movement which taps into mass rage and desire by challenging this structure can hope to become strong enough to prevent the catastrophe.

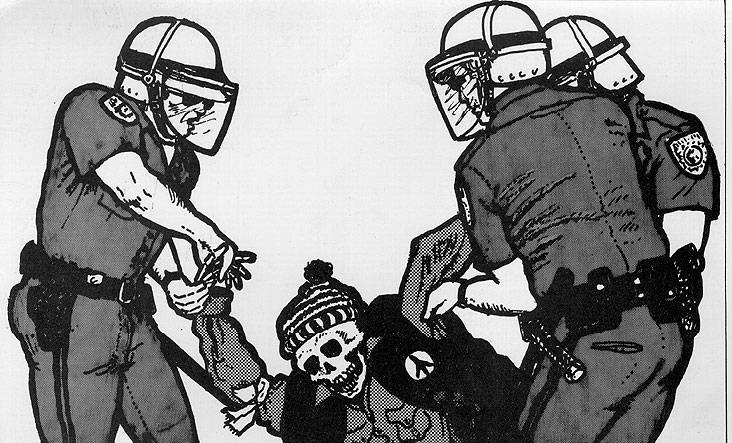

Illustration: Adam Cornford

CRAZY LIKE A FOX

Contrary to Helen Caldicott's cliches, the military buildup is not "madness" in the sense of arbitrary folly. The nuclear planners have cold, pragmatic, non-ideological reasons for their actions. Nukes are (and always have been) a vital form of social control. They are being used to pressure the NATO countries back into line, preventing them from becoming a new political-economic bloc with even stronger ties to the East. At home, they force us back toward the Cold War choice of "pro-American" vs. Soviet apologist. Military spending is a good excuse to cut the social wage and break up the growing mass of un-workers," young people who work as little as possible and create a dangerous link between employed and unemployed.

Most important is the increase in the intangible levels of fear and authoritarianism. The empire benefits from the threat to third world nationalist movements, and helps guarantee low wages and the resulting high rates of profit. The growing fear of nukes is partly counteracted by the highly successful campaign to make the military appear sexy and glamorous, a vital force sailing through the Golden Gate. A recent poll shows the military as one of the two most trusted institutions in American society, while Army recruiters now need only accept high-school graduates. The Pentagon and the corporations have their own ways of channeling rage and desire.

NEW WAYS OUT

THE lockstep toward war begins with the acceptance of hierarchical social discipline—on the job, in the polling booth, in the family, in church, in bed. The West German peace movement is as successful as it is partly because its most committed elements know this—they are Hitler's grandchildren. Within, around and beneath the peace movement is a proliferation of challenges to governmental and corporate power.

In Berlin, young squatters refuse to pay for housing, claiming it as a right. In Frankfurt, auto workers join senior citizens, teenage punkers, and ecological activists in fighting the construction of a new airport extension that would wipe out the last forest in the area. In these and other cities, the feminist movement creates social space for women to explore their own bodies, desires, imaginations without male interference. In the countryside, the battle against nuclear power continues, in the face of clubs, attack dogs, water cannons, machine guns.

Not so much a "counter-culture" as a collection of evolving cultural mutations, this movement behind the movement is asking fundamental questions about the nature of social life and how it could be different. It is also coming up with widely divergent answers—which is as it should be. But it knows its enemies, and is not afraid of its own anger. These people are not just "questioning" Authority, they are attacking it. We should be doing no less.