Murder in the Moana: The Death of Jane Stanford

Historical Essay

by Nathan Weiser, 2015

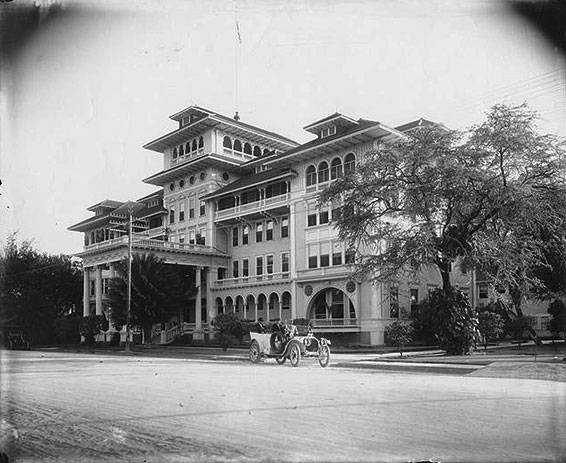

Moana Hotel, Honolulu, c. 1908.

Honolulu, 1905

Jane Stanford, widow of Central Pacific Railroad Company President Leland Stanford and mother of the deceased University namesake, died on February 28, 1905 in her room at the Moana Hotel in Honolulu, Hawaii Territory. Those present included her faithful maid and travelling companion, Bertha Berner, and a local doctor, Dr. Francis Humphris, who concluded that she had died of strychnine poisoning. This verdict was supported by a coroner’s jury of medical experts, that, after examining the evidence, released a joint statement affirming that Stanford had been poisoned “by some person or persons… unknown.”(1) The poisoning, which was supposedly accomplished by putting strychnine in her bicarbonate of soda, had a frightful precedent: Ms. Stanford had nearly died on January 14 in her Nob Hill mansion after drinking bottled water with nux vomica (rat poisoning) placed in it. Private detectives hired to investigate the case had deemed it an accident: now, it seemed that something more sinister was a foot.

San Francisco Call, 1905

News of Stanford’s sudden death dominated the headlines in San Francisco, with sensational and often speculative coverage of the still-unfolding events in Hawaii replacing accounts of the Russo-Japanese War on the front pages.The city police, in collaboration with the earlier cases’ private detectives, launched an investigation, narrowing the list of suspects down to three servants who had access to Stanford’s possessions before both poisonings: Elizabeth Richmond, a recently British maid and the private detective’s favorite suspect in the earlier attempt; former butler Alfred Beverley, also British and a close friend of Richmond’s; and Ah Wing, Stanford’s fiercely loyal Chinese cook who was singled out for harsh treatment by police officers.(2) All of these suspects were eventually cleared of suspicion. Interestingly, one new person of interest emerged: Bertha Berner, who was with the deceased during both poisonings and gave inconsistent testimony about the lead-up to the murder.(3) However, the investigation’s growing suspicion of Berner was undercut by the surprising entrance of Dr. David Starr Jordan, the President of Stanford University and a prominent public intellectual in his own right.

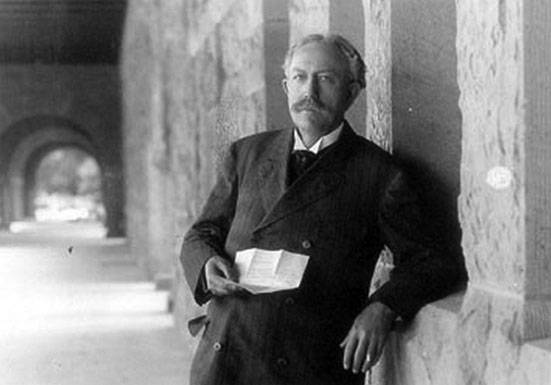

David Starr Jordan, photographed in the mid-1890s.

Photo: “Stanford University and the 1906 Earthquake”

Jordan had travelled to Hawaii, where he often performed research and had many political connections, with the stated intention of retrieving Stanford’s body for burial. Arriving in Honolulu, he hired a doctor from a prominent local family, Dr. Ernest Waterhouse, to review the coroner’s verdict. Waterhouse disagreed with the poisoning diagnosis, albeit without examining Stanford’s corpse himself, citing Berner’s testimony to claim that the woman had died of angina pectoris.(4) Jordan embraced this theory, telling the press upon his return to San Francisco that Stanford died of natural causes. He also argued that the Honolulu physicians had added strychnine to the bicarbonate of soda post-poisoning in order to exert an additional fee from the deceased’s estate(5) . The Honolulu doctors, men of high standing in their community, were understandably irked by Jordan’s announcements and complained that Waterhouse had sabotaged their investigation, a claim that made big news in the Honolulu papers(6) and nowhere else.(7) They hounded Waterhouse incessantly, trying to get him to recant his diagnosis. He fled for the British colony of Ceylon in relative disgrace.(8) Jordan also publically asserted Berner’s good character and close kinship with Stanford, asserting her innocence all over the city’s papers. Stymied and out of leads, the police investigation disintegrated. An unrelated scandal shook up the police department’s leadership, and Stanford’s murder got lost in the confusion.(9) Officially, the case remains unsolved to this day.

Jane Stanford’s murder will probably go unsolved. There is no corpse to prod for undiscovered mysteries and no certainty to be drawn from the possibly compromised evidence collected during the contemporary investigation. While unmistakably tragic, the events of 1905 offer valuable insights into a long-passed culture as peculiar and darkly fascinating as our own.

Clash of Cultures

Those who accuse Jordan of covering up (or perhaps facilitating) Jane Stanford’s murder find potential motive in the fractious relationship between the two of them in the years leading up to her murder. Each represented opposing elements of late Gilded Age culture and had wildly opposed visions of the university’s future. Stanford, very much a Victorian woman, favored a traditional liberal arts curriculum, while Jordan embraced Alexander von Humboldt’s research and sciences-focused approach, pioneered in the United States at Johns Hopkins University. The two fought over funding and personnel in aseries of public controversies, most notably during Jane’s termination of Edward Ross, a legendary American sociologist and progressive activist whose anti-Asian prejudices and support for William Jennings Bryan the widow considered offensive.(10)

The two were also both associated with cultural movements contemporary Americans often look at with befuddlement or contempt. Stanford, like many other elites of the late 19th century, was affiliated with spiritualism, a semi-organized pseudo-religion that preached the ability of the living to communicate with the dead. This is somewhat understandable in Jane, who loved her deceased son and husband dearly and mourned them her entire life. Spiritualist influence can still be seen on the Stanford campus today: its oft-photographed Memorial Church includes Jane’s own spiritualist writings inscribed on the wall(11) and a stained glass depiction of Leland Stanford Jr. trapped between Heaven and Earth, his body portrayed like Christ’s. Jordan, a man of science, resented these beliefs, and opposed Stanford’s attempt to bring philosopher William James, a famous advocate of paranormal research, to Palo Alto as a visiting professor.(12) He was unsuccessful, of course – James arrived but did not find the university to his liking, inconspicuously boarding a train back east during the turmoil of the 1906 earthquake.(13)

Jordan, meanwhile, aligned himself with America’s nascent eugenics movement. This he made public towards the end of his term as President, advocating for government-instituted “selective breeding” in several books and as the chair of the American Breeder’s Association’s Committee on Eugenics.(14) His opinions were not uncommon in this era as racial prejudice amongst the masses blended with academic over-interpretations of Darwinism. Eugenics supporters like Jordan reached their highest level of political acceptance in the Supreme Court case of Buck v. Bell (1927), which saw Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. infamously claim “three generations of imbeciles are enough.” While Jordan’s eugenicist beliefs were not entirely present during his relationship with Jane Stanford, they undeniably reflected the scientific worldview that alienated them from each other and may have led to her murder.

Mass Communication and Racism

Studying Jane Stanford’s murder also reveals many aspects of life as it was lived by ordinary San Franciscans on the city’s teeming streets, rather than in the stuffy mansions and lecture halls of Nob Hill and Palo Alto. The reckless Yellow Journalism coverage the case received revealed the population’s problematic and mutually perpetuated relationship with the press. Newspapers published stories about the murder that were lurid and filled with falsehoods. Headlines proclaimed “imminent arrests”(15) that never came, described nonexistent evidence, and vilified suspects Richmond and Ah Wing for the sole purpose of selling papers. When police suspicion in Bertha Berner increased, papers helped dull the investigation by accepting Jordan’s of her innocence and Dr. Waterhouse’s interpretation without careful consideration.(16)

It would be easy to blame this journalistic failure solely on opportunistic publishers, greedily trying to outsell each other. This neglects the public’s embrace of prejudicial values that the newspapers were able to exploit. Anti-Chinese sentiment had run rampant in the city practically since its inception. This sentiment was distinguished from anti-Chinese racism elsewhere in the country by what scholar Nayan Shah calls Chinatown’s “queer domesticity”: the white upper-middle class authorities feared the area’s bending of conventional household norms and the opportunities it offered white citizens to escape rigid Victorian norms.(17) Papers were cruel in their coverage of Ah Wing, who they knew would make a marketable public whipping boy.(18) They never treated him fairly, referring to him as a “Mongolian.”(19) After he was proven innocent, their vile behavior continued unabated: the San Francisco Chronicle called Ah Wing “a bad man and a liar” in a passage admitting, reluctantly, that he did not have “the least connection with Mrs. Stanford’s death.” It is possible to see the demonization of Ah Wing in the context of the Russo-Japanese War, at full swing in 1905, which lead Americans to view an Asian, non-white ethnic group as able to overcome a nationality of European descent. This was a time of fear disguised as bigotry: poor, innocent Ah Wing got caught up in a parasitic media infrastructure that knew its buyers, the city’s citizens, all too well.

110 Years Later

The bizarre circumstances surrounding Jane Stanford’s death are still fairly unknown to the general public. This may soon change. In 2003, Dr. Robert Cutler published The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford, a logical and well-written destruction of Jordan’s reasoning that renews interest in Berner as a suspect.Students at Stanford University are now more aware of the macabre secrets lying beneath their school’s past – in 2014, a class of undergraduates (including myself) led by Professor Richard White examined the case. We voted, unanimously, to posthumously “indict” Bertha Berner and David Starr Jordan for murder and obstruction of justice, respectively. Still, not enough evidence exists to say anything definitively about who killed whom and why – although Berner’s behavior was certainly suspicious, it is hard to say why she would kill her employer and close friend. Police files relating to the case are believed to have been destroyed during the 1906 fire.

Statue on Stanford campus of Leland Stanford, his wife Jane, and their son Leland Stanford, Jr., after whom the University is named.

But the death of Jane Stanford is still worth studying. It provides an illuminating glimpse into the social realities of early 20th century life in San Francisco and America, both for elites and the common folk. It is a story worth telling and retelling and learning from, even if the story itself refuses to tie off satisfactorily.

Works Cited

Bandura, Albert. "William James' Shaky Sojourn in Stanford." Observer 19.1 (2006): n. pag. Web. 22 May 2015.

Cutler, Robert W. P. The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford. Stanford, CA: Stanford General, 2003. Print.

Johnston, Theresa. "Meet President Jordan." Stanford Magazine Jan.-Feb. 2010: n. pag. Stanford Magazine. Web. 21 May 2015.

"Memorial Church Inscriptions." Office for Religious Life RSS. Stanford University, n.d. Web. 22 May 2015. <http://web.stanford.edu/group/religiouslife/cgi-bin/wordpress/memorial-church/history/memorial-church-inscriptions/>.

Shah, Nayan. Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco's Chinatown. Berkeley: U of California, 2001. Print.

Various issues of San Francisco Call, Hawaiian Star and San Francisco Chronicle, accessed online through Chronicling America website. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

Footnotes

1. Robert Cutler, The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003),45.

2. Ibid 28-29.

3. Ibid 102-108.

4. Ibid 47-54.

5. San Francisco Call, March 21, 1905.

6. Headline: “STANFORD CASE WILL NOT DOWN. WATERHOUSE ADVISED JORDAN.” Hawaiian Star, August 26, 1905.

7. Robert Cutler, The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 75.

8. Ibid 68-69.

9. Headline: “CHIEF OF POLICE GEORGE W. WITTMAN DISMISSED FROM THE DEPARTMENT.” San Francisco Call, March 25, 1905.

10. Robert Cutler, The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 114-121.

11. “Memorial Church Inscriptions,” Office for Religious Life RSS, accessed May 22, 2015.

12. Robert Cutler, The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 32.

13. Albert Bandura, “William James’ Shaky Sojourn in Stanford,” Observer 19, no. 1 (2006).

14. Theresa Johnston, “Meet President Jordan,” Stanford Magazine Jan-Feb 2010.

25. A quote from an article whose headlines include “TWO ARE UNDER SUSPICION” and “EVIDENCE IS ACCUMULATING.” All falsehoods. San Francisco Call, March 22, 1905.

16. Robert Cutler, The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 75.

17. Nayan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco's Chinatown (Berkeley: U of California Press, 2001), 77-79.

18. Headline: “CHINESE COOK SUSPECTED OF POISONING MRS. STANFORD.” Noticeably does not mention any of the other two suspects, the article below defames Ah Wing’s character. San Francisco Call, March 3, 1905.

19. Robert Cutler, The Mysterious Death of Jane Stanford (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 29.