Marinship to Marin City: How a Shipyard Built a City

Historical Essay

by April Harper

| During World War II, Marin City, CA was a bustling and diverse shipbuilder's town. Today, Marin City is predominantly African American and plagued by poverty, but is surrounded by some of the whitest and wealthiest suburbs in the nation. How did this happen? The social and demographic changes of war are both far-reaching and deeply entrenched. Marin City exemplifies this demographic shift, as told through the lens of the Marinship shipyards. |

The Beginning

Marin City was founded in 1942, when housing was built for employees who worked at the nearby Marinship Corporation during World War II, building ships for the war effort. Marinship was one of many early 1940s emergency shipyards established on the West Coast to fuel America’s need for oil tankers and Liberty Ships, or war cargo ships, which, while originally a British design, were adopted due to their fast construction and low cost to produce. (1) The West Coast was an ideal place to establish the wartime shipyards due in part to its undeveloped coastline and thus plentiful space on which to build, the natural harbors present there, and its proximity to the Pacific, so the ships could be constructed and launched from the same point. Additionally, the Bay Area was well-connected to the nation’s railroads, which transported partially assembled steel parts from steel towns in the Midwest. (2) Other notable emergency shipyards included Kaiser Permanente shipyards in Richmond, California and Portland, Oregon, as well as Mare Island in Vallejo and Hunter’s Point in San Francisco.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/chi_00005" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Industrial film by and about Marinship, from 1945.

Video: Internet Archive

In the early 1940s, many African Americans migrated from the Southern states in search of shipbuilding work, after being excluded from higher-paying industrial jobs back home. It was not uncommon for a shipbuilder to make in an hour what they formerly made in a day in the South. Shipbuilding had gained a reputation as steady work that paid generous wages and included family housing; ultimately it was these benefits which attracted African Americans to the area. The town of Marin City was formed by building housing, churches, and schools to accommodate 6,000 newly arrived workers. After the Attack on Pearl Harbor, America suddenly had an urgent need for warships, and employees worked around the clock in shifts; at the height of Marinship’s production, a new ship was produced every thirty days. Employees worked as welders, ship painters, and boilermakers, and as many other skilled laborers. (3)

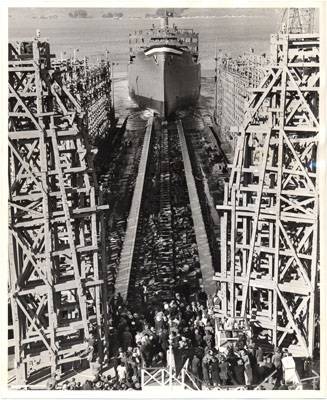

At 5:30 this afternoon the S.S. Escambia, the first big ocean-going tanker to be launched in San Francisco Bay for 21 years, slid down the ways at Marinship's Sausalito yard in a riot of sound with tug and Gantry crane whistles and the cheers of thousands of employees and their families all joining in. The ship was christened by Mrs. Lorraine Cooper, wife of a shipfitter journeyman, and her matron of honor was Mrs. Helen Vargas, wife of a welder foreman, while Mr. Al Gracey, Superintendent of the Hull Division, acted as Master of Ceremonies. The entire program was conducted by the workers who had built this beautiful ship - number one of the 22 tankers on Marinship's 1943 schedule. The first nine tankers are being taken over by the U.S. Navy and are being named after Indian rivers in accordance with Navy nomenclature for their ships. The photo shows the dramatic bottle-breaking, left to right: R.W. Adams, Marinship Employee Relations Manager; Mrs. Cooper, and E.B. Fox, Maritime Commission.

Photo: San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco History Center

The quick construction and operation of the shipyards could not have been possible without the cooperation of both government and private enterprise; indeed, shipbuilding is thought of as the one of the biggest combined efforts between government and private industry. This cooperation resulted in extremely high productivity. During the war, which lasted 1365 days, Bay Area shipyards produced 1400 vessels. Collectively, that’s over a ship per day! (4)

Image: courtesy of Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park.

This cooperative spirit also extended to the workers themselves. Marin City residents looked out for one another and were familiar with neighboring family’s work schedules. Meals and celebrations were often had together. In this way, the shipyards produced a tight-knit community. (5) Annie Small, a Marinship worker, described the community:

“Everybody got along swell because everybody acted as a family unit, everybody helped everybody else. It was such a such a mixture of all kinds of ethnic groups and ages and the work habit was...everybody worked around the clock. There was someone going to work 24 hours a day... So there was always somebody at the house, I kept theirs or they kept mine. Somebody was goin’ and comin’ at all times and when we moved to Marin City, I worked the day shift, and my husband worked the night shift. So when he come in in the morning he would bring the kids to the school...when I got off at five in the evening, I picked 'em up. And so, your neighbor, if it rained, they took my clothes in, cause they know I’m going to work. And of course the iceman and milkman came, and I would let them in for them... We didn't have to lock the door. We never locked no doors... You could team up and go to Santa Rosa or Petaluma and buy a whole hog and cook it together.” (6)

Attempts to keep morale high and employees happy resulted in many services provided for them by Marinship, such as health care and child care. At lunch, workers were entertained by celebrities such as Bing Crosby or swing bands, and talented workers often played piano and sang. (4) All told, Marinship employed 75,000 workers and contributed over 100 million man hours of labor to the war effort. (7)

Representing twenty or more shipyard crafts. Women war workers at Marinship, shipyard at Sausalito on San Francisco bay, act as a guard of honor to the national Tanker Champ flag. The flag was presented to Marinship by the U.S. Maritime Commission for defeating all other U.S. shipyards in the production of tankers in March. This float was a unit in a triumphal parade led by the Fourth Army Band and joined in by 5,000 workers.

Photo: San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco History Center

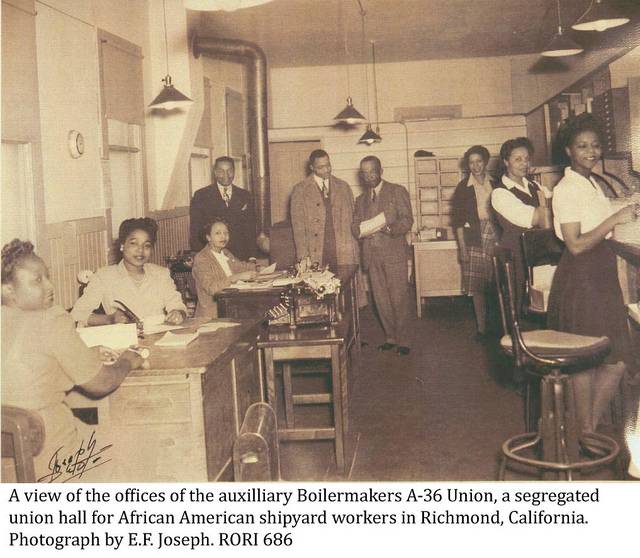

While many African Americans were part of the shipbuilding labor force, it was diverse and included people of white and Asian ethnicities as well. Race relations were considered peaceful on the job because of Marinship’s cooperative spirit; Thelma McKinney, a Marinship worker, recalled that at the yard, “there was no such thing as segregation” and that everyone was too busy “[to] have time for racism” (8). But outside the shipyard, tensions still festered; many Sausalito restaurants refused to serve blacks, and discrimination in the form of union benefits was a regular occurrence. The Boilermaker Union, a traditionally “lily-white” union, only allowed black workers as “auxiliary” members, who were unable to vote on union matters and received smaller insurance benefits. (9) That is, until November 1943, when African-American Marinship workers from around the Bay Area went on strike and refused to pay their auxiliary member dues; the matter was finally resolved by the Supreme Court in 1945, finding that it was “readily apparent that the membership offered to Negroes is discriminatory and unequal.” (10)

The Closing of Marinship

Marinship closed in May 1946, and as the war wound down, black employment also decreased. In July 1945, 20,000 African-American Marinship workers were employed; by September 1945, that number was reduced to 12,000 and by Marinship’s closing, there were almost none. Wollenberg (1990) states that it was a case of “last hired, first fired” when it came to black workers. At the height of the war, about 75 percent of San Francisco black heads of households were classified as skilled industrial workers, the great majority of them in the shipyards, but by 1948, this number had dwindled to 25 percent, and many were forced to take lower paying jobs in unskilled industry or service sectors. The unemployment rate for African Americans had risen to 15 percent, 3 times the national average. The US Department of Employment noted a couple years later, in 1950, that, “as long as Negroes (sic) are commonly regarded as marginal labor, they will suffer very heavy unemployment when sufficient white labor is available.”(11)

Image: courtesy of Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park.

Due to such employment discrimination, many black Marin City residents found they could not afford to leave, and those that could afford it were unable to relocate, due to the discriminatory rental and homeowner statutes that stipulated against renting to minorities, common throughout the Bay Area until the 1960s. The plight of the black Marinship workers, and of those in nearby Richmond/Oakland and Hunter’s Point shipyards, was unique in that the African-American population increase was due to a boom in just one industry, which, when it dried up, left little economic opportunity. (12)

Marin City Today

Today, Marin City remains a contrast to the surrounding affluent, white suburbs that Marin County is known for. It remains predominantly African-American and poor, with many residing in the public housing that was built in the mid-1950s, after much of the shipyard housing was demolished. This tract of affordable housing remains only one of a few in the entire county of Marin, thought to have some of the most expensive housing prices in the nation. (13)

African Americans in Marin City also experience a lower life expectancy than the surrounding towns of Sausalito, Mill Valley, and Corte Madera. In fact, African Americans have the lowest life expectancy of all ethnicities residing in Marin, at 79.5 years compared to 83.5 years for a Caucasian person and 90.9 years for an Asian person. A person residing in Ross, one of Marin’s richest towns, has a life expectancy of 88 years, while a resident of Marin City has a life expectancy of only 77 years. Indeed, one of the biggest causes of gaps in health is access to healthy food; Marin City is easily a “food desert”, defined as “low-income neighborhoods without ready access to healthy and affordable food. Typically, convenience stores, fast food outlets, and liquor stores predominate.” (14) With the only market being a CVS drugstore and assorted fast food restaurants like Burger King and Panda Express, Marin City definitely fits this description. The nearest Safeway is over two miles away in Mill Valley, and the Mollie Stone’s market in neighboring Sausalito is prohibitively expensive.

Additionally, social connections which create tight-knit communities are more absent here; many Marin City residents don’t own cars and must take the bus, which has limited stops and departure times in the neighborhood. In a 2015 Marin Independent Journal article, Julie Willems Van Dijk, director of County Health Rankings and Roadmaps program, states, “...the evidence continues to show that it’s not simply lower levels of income that affect health,” Van Dijk said. “The income divide also influences health as well. “We also see the potential for more social division and less social connectedness in communities where there is a great divide between richer and poorer populations,” she said. “And we know that stronger social connection contributes to good health within a community.” (15) Such isolation, then, also contributes to a lower quality of life for Marin City residents.

While Marin City remains a more affordable place to live within expensive Marin County, its future remains uncertain. You can buy a two bedroom, one bath condo for $229,000 here, unheard of in any other part of Marin. (16) Recently, worries have surfaced that Marin City, and the affordable housing complex specifically, are targets for gentrification, which would push the low income residents out. In a San Francisco Chronicle piece, resident Homer Hall, who moved here in 1955, shares these fears, saying, “Whites wouldn’t live here [back then]. Now the White are looking at it like it’s gold - they can’t get here fast enough.” (17) Hall’s anxieties are shared by other neighborhoods around the Bay Area that are home to minorities, many of which are shipbuilder’s descendants, like in Richmond, West Oakland, and Bayview-Hunter’s Point. For now though, these residents do their best to preserve their neighborhood’s colorful history, in an attempt to keep their streets both diverse and affordable.

Notes

1. Bonnett, Wayne. World War II Shipbuilding in the San Francisco Bay Area. National Park Service. Accessed November 28th, 2015.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Tanker. Directed by Paul Crowley. 1945. Sausalito, CA: Marinship Corporation, 1945. Accessed November 28th, 2015.

5. Marinship Memories. Directed by Joan Lisetor. 2009. Sausalito, CA: Marin City Performing Arts, 2009.

6. Ibid.

7. Tanker.

8. Wollenberg, Charles. Marinship at War: Shipbuilding and Social Change in Sausalito. Sausalito, CA: Western Heritage Press, 1990.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Perrigan, Dana. "Marin City Looks to Better Days." San Francisco Chronicle, (San Francisco, CA) March 15, 2009.

14. Burd-Sharps, Sarah and Kristen Lewis. "A Portrait of Marin: Marin County Human Development Report 2012." American Human Development Project, 2012.

15. Halstead, Richard. "Marin Ranked Healthiest County in State for Sixth Year but Economic Inequality a Pitfall." Marin Independent Journal, (Novato, CA), March 25, 2015.

16. Perrigan.

17. Ibid.